Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

Spanish Master Drawings from Cano to Picasso

Spanish Master Drawings From Cano to Picasso Spanish Master Drawings From Cano to Picasso When we first ventured into the world of early drawing at the start of the 90s, little did we imagine that it would bring us so much satisfaction or that we would get so far. Then we organised a series of five shows which, with the title Raíz del Arte (Root of Art), brought together essentially Spanish and Italian drawing from the 16th to 19th centuries, a project supervised by Bonaventura Bassegoda. Years later, along with José Antonio Urbina and Enrique Calderón, our friends from the Caylus gallery, we went up a step on our professional path with the show El papel del dibujo en España (The Role of Drawing in Spain), housed in Madrid and Barcelona and coordinated by Benito Navarrete. This show was what opened up our path abroad via the best possible gate- way, the Salon du Dessin in Paris, the best drawing fair in the world. We exhibited for the first time in 2009 and have kept up the annual appointment with our best works. Thanks to this event, we have met the best specialists in drawing, our col- leagues, and important collectors and museums. At the end of this catalogue, you will find a selection of the ten best drawings that testify to this work, Spanish and Italian works, but also Nordic and French, as a modest tribute to our host country. I would like to thank Chairmen Hervé Aaron and Louis de Bayser for believing in us and also the General Coordinator Hélène Mouradian. -

A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture

COVERFEATURE THE PAAMPROVINCETOWN ART ASSOCIATION AND MUSEUM 2014 A Stellar Century of Cultivating Culture By Christopher Busa Certainly it is impossible to capture in a few pages a century of creative activity, with all the long hours in the studio, caught between doubt and decision, that hundreds of artists of the area have devoted to making art, but we can isolate some crucial directions, key figures, and salient issues that motivate artists to make art. We can also show why Provincetown has been sought out by so many of the nation’s notable artists, performers, and writers as a gathering place for creative activity. At the center of this activity, the Provincetown Art Associ- ation, before it became an accredited museum, orga- nized the solitary efforts of artists in their studios to share their work with an appreciative pub- lic, offering the dynamic back-and-forth that pushes achievement into social validation. Without this audience, artists suffer from lack of recognition. Perhaps personal stories are the best way to describe PAAM’s immense contribution, since people have always been the true life source of this iconic institution. 40 PROVINCETOWNARTS 2014 ABOVE: (LEFT) PAAM IN 2014 PHOTO BY JAMES ZIMMERMAN, (righT) PAA IN 1950 PHOTO BY GEORGE YATER OPPOSITE PAGE: (LEFT) LUCY L’ENGLE (1889–1978) AND AGNES WEINRICH (1873–1946), 1933 MODERN EXHIBITION CATALOGUE COVER (PAA), 8.5 BY 5.5 INCHES PAAM ARCHIVES (righT) CHARLES W. HAwtHORNE (1872–1930), THE ARTIST’S PALEttE GIFT OF ANTOINETTE SCUDDER The Armory Show, introducing Modernism to America, ignited an angry dialogue between conservatives and Modernists. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

A Cta ΠCumenica

2020 N. 2 ACTA 2020 ŒCUMENICA INFORMATION SERVICE OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN UNITY e origin of the Pontical Council for Promoting Christian Unity is closely linked with the Second Vatican Council. On 5 June 1960, Saint Pope John XXIII established a ‘Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity’ as one of the preparatory commissions for the Council. In 1966, Saint Pope Paul VI conrmed the Secretariat as a permanent dicastery CUMENICA of the Holy See. In 1974, a Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews was established within the Secretariat. In 1988, Saint Pope John Paul II changed the Secretariats status to Pontical Council. Œ e Pontical Council is entrusted with promoting an authentic ecumenical spirit in the Catholic Church based on the principles of Unitatis redintegratio and the guidelines of its Ecumenical Directory rst published in 1967, and later reissued in 1993. e Pontical Council also promotes Christian unity by strengthening relationships CTA with other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, particularly through A theological dialogue. e Pontical Council appoints Catholic observers to various ecumenical gatherings and in turn invites observers or ‘fraternal delegates’ of other Churches or Ecclesial Communities to major events of the Catholic Church. Front cover Detail of the icon of the two holy Apostles and brothers Peter and Andrew, symbolizing the Churches of the East and of the West and the “brotherhood rediscovered” (UUS 51) N. 2 among Christians on their way towards unity. (Original at the Pontical -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles

Clerical Sexual Abuse in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 Attorney Advertising “For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: it happened everywhere.” ~ Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report 2018 AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 2 Attorney Advertising Table of Contents Purpose & Background ...........................................................................................9 History of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles ...........................................................12 Los Angeles Priests Fleeing the Jurisdiction: The Geographic Solution ....................................................................................13 “The Playbook for Concealing the Truth” ..........................................................13 Map ........................................................................................................................16 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Documents ...............................................................17 Those Accused of Sexual Misconduct in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles ..... 38-125 AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 3 Attorney Advertising Clerics, Religious Employees, and Volunteers Accused of Sexual Misconduct in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles Abaya, Ruben V. ...........................................39 Casey, John Joseph .......................................49 Abercrombie, Leonard A. ............................39 Castro, Willebaldo ........................................49 Aguilar-Rivera, -

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING and SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Js'i----».--:R'f--=

Arch, :'>f^- *."r7| M'i'^ •'^^ .'it'/^''^.:^*" ^' ;'.'>•'- c^. CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign jS'i----».--:r'f--= 'ik':J^^^^ Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture 1969 Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture DAVID DODD5 HENRY President of the University JACK W. PELTASON Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Urbano-Champaign ALLEN S. WELLER Dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts Director of Krannert Art Museum JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Chairman Frank E. Gunter James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Christlson, Associate Director Lois S. Frazee, Registrar Marie M. Cenkner, Graduate Assistant Kenneth C. Garber, Graduate Assistant Deborah A. Jones, Graduate Assistant Suzanne S. Stromberg, Graduate Assistant James O. Sowers, Preparator James L. Ducey, Assistant Preparator Mary B. DeLong, Secretary Tamasine L. Wiley, Secretary Catalogue and cover design: Raymond Perlman © 1969 by tha Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A48-340 Cloth: 252 00000 5 Paper: 252 00001 3 Acknowledgments h.r\ ^. f -r^Xo The College of Fine and Applied Arts and Esther-Robles Gallery, Los Angeles, Royal Marks Gallery, New York, New York California the Krannert Art Museum are grateful to Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New those who have lent paintings and sculp- Fairweother Hardin Gallery, Chicago, York, New York ture to this exhibition and acknowledge Illinois Dr. Thomas A. Mathews, Washington, the of the artists, Richard Gallery, Illinois cooperation following Feigen Chicago, D.C. collectors, museums, and galleries: Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, Midtown Galleries, New York, New York New York ACA Golleries, New York, New York Mr. -

X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

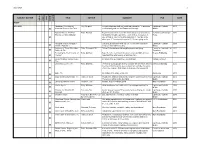

2/25/2020 1 SUBJECT MATTER TITLE AUTHOR SUMMARY PUB DATE DVD gdom VIDEO AUDIO OTHER OTHER AUDIO 2/12/2020 Abraham: Revealing the Ray, Stephen To understand our faith, we must understand the "Jewishness" Lighthouse Catholic 2011 x Historical Roots of our Faith of Christianity and our Old Testament Heritage Media Adam's Return: The Five Rohr, Richard Boys become men in much the same way across cultures, by St. Anthony Messenger 2006 Promises of Male Initiation integrating, through experience, each of these messages: 1. Press x Life is hard; 2. You are not that important; 3. Your life is not about you; 4. You are not in control; 5. You are going to die. Amazing Angels and Super Cat.Chat, designed for kids ages 3-11, to teach lessons for Lighthouse Catholic 2008 x Saints - Episode 1 living out their faith every day Media Authority of Those Who Have Rohr, Richard OFM Father Richard shares his insights on pain and dying Center for Loss and Life 2005 x Suffered, The Transition Becoming the Best Version of Kelly, Matthew Take life to the next level: who you become is infinitely more Beacon Publishing 1999 x Yourself important than what you do or what you have. Best of Catholic Answers Live, 47 answers to questions from non-Catholics Catholic Answers x The Best Way to Live, The Kelly, Matthew Perfect for young paople as they consider the life before them at Beacon Publishing 2012 the time of Confirmation; also an important reminder for adults x of any age, and one that is sure to help you refocus your life x Bible, The Recitation of the Bible on 64 cd's Zondervan 2001 Body and Blood of Christ, The Hahn, Dr. -

Oral History Interview with Beaumont Newhall, 1965 Jan. 23

Oral history interview with Beaumont Newhall, 1965 Jan. 23 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Beaumont Newhall on January 23, 1965. The interview was conducted at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York by Joseph Trovato for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview JOSEPH TROVATO: This interview with Mr. Beaumont Newhall is taking place at George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, January 23, 1965. Mr. Newhall, your name has been associated with the best in the field of photography for many years, or just about as long as I can remember, from the early days of the Museum of Modern Art, your writings on photography, such as The History of Photography, which has gone through several editions, I think, and on through to your present directorship here at Eastman House. How long have you held your present post here? BEAUMONT NEWHALL: Actually my present post as director I assumed the first of Sept. 1958. Previous to that I held the title of curator and worked as the associate and assistant to the first director, General Oscar N. Solbert. I came to Rochester for the specific purpose of setting up Eastman House as a museum, bringing to it my knowledge of museum practice, as well as photography. We opened as a museum to the public on the 7th of November, 1949. JOSEPH TROVATO: Well I was about to ask you in addition to my question regarding your career and while we’re on the subject of your career – I think you have already begun to touch upon – we would like to have you give us a sort of resume of your background, education, various positions that you have held, and so forth. -

The Fall Into Oblivion of the Works of the Slave Painter Juan De Pareja. Art in Translation, 4 (2)

Fracchia, C., and Macartney, H. (2012) The Fall into Oblivion of the Works of the Slave Painter Juan de Pareja. Art in Translation, 4 (2). ISSN 1756-1310 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/68437/ Deposited on: 4 September 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Art in Translation, 4:2 (June 2012), 63-84, translated by Hilary Macartney The Fall into Oblivion of the Works of the Slave Painter Juan de Pareja Carmen Fracchia Birkbeck College, University of London, UK In this essay I will focus on the mechanisms of forgetting and oversight of the works of the Spanish artist Juan de Pareja (Antequera, c. 1606 – Madrid, 1670), and the consequent lack of critical recognition he has suffered up to the last ten years. Juan de Pareja was a mulatto painter and slave who succeeded in forging an independent artistic career in seventeenth-century Spain, at a time when, in theory, only those who were free could practice the art of painting. Pareja was the slave and collaborator of the celebrated painter Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) at the court of Philip IV in Madrid, where he was an exceptional case, as was also the relationship between master and slave.1 Pareja, who was able to read and write, acted as legal witness for Velázquez in documents dating from 1634 to 1653, both in Spain and in Italy, where he went with his master from 1649 to 1651.2 During Velázquez’s second stay in Italy, he immortalized his slave in an extraordinary portrait which he exhibited in the Pantheon in Rome on 19 March 1650,3 six months before he signed the document of manumission of Pareja. -

John Ferren (American Painter, 1905-1970)

237 East Palace Avenue Santa Fe, NM 87501 800 879-8898 505 989-9888 505 989-9889 Fax [email protected] John Ferren (American Painter, 1905-1970) John Ferren was one of the few members of the American abstract artists to come to artistic maturity in Paris. A native of California, in 1924 Ferren went to work for a company that produced plaster sculpture. He briefly attended art school in San Francisco. Later he served as an apprentice to a stonecutter. By 1929, Ferren had saved enough money to go to Europe, stopping first in New York where he saw the Gallatin Collection. He went to France and to Italy. In Saint-Tropez, he met Hans Hofmann, Vaclav Vytlacil, and other Hofmann students. When Ferren stopped to visit them in Munich, he saw a Matisse exhibition, an experience that was instrumental in shifting his work from sculpture to painting. In Europe, Ferren did not pursue formal art studies, although he sat in on classes at the Sorbonne and attended informal drawing sessions at the Academie Ranson and the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere. Instead, Ferren said, he "literally learned art around the cafe tables in Paris, knowing other artists and talking." After this initial year in Europe, Ferren returned to California. By 1931 he was again in Paris, where he lived for most of the next seven years. Surrounded by the Parisian avant-garde, Ferren wrestled with his own idiom. His diaries from these years indicate far-ranging explorations from a Hofmann-like concern for surface to the spiritual searches of Kandinsky and Mondrian.