Hollywood Goes to Tokyo: American Cultural Expansion and Imperial Japan, 1918–1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE PUBLISHER PRICE CONDITION ? ? the Life of Fancis Covell E

LAST NAME FIRST NAME TITLE PUBLISHER PRICE CONDITION ? ? The Life of Fancis Covell E. Wilmshurst, Blackheath $15 poor to fair ? ? Good Housekeeping's Book of Meals Good Housekeepind $23 poor ? ? A Supreme Book for Girls Dean & Son $10 good ? ? Personal Hygiene for Every Man and Boy A Social Guidance Enterprises $13 fair Abbey J. Biggles in Spain Oxford University Press $13 good with d/c Abbot Willis The Nations at War Leslie-Judge Co. $35 fair to good Abbott Jacob Mary Queen of Scots Makers of History $12 good Adler Renata Gone Simon & Schuster $20 Excellent with d/c Ainsworth William The Tower of London W. Foulsham $20 fair Ainsworth W. H. Windsor Castle Collins $8 fair to good Ainsworth W. H. Old St. Paul's Collins $10 good Ainsworth William Rookwood George Routledge and Sons $13 good to excellent Ainsworth W. H. The Tower of London Collins $5 good to excellent Alcott Louisa May Little Men Whitman Publishing Company $10 good Alcott Louisa May Little Women Goldsmith $22 good Alcott Louisa May Eight Cousins Whitman Publishing Company $7 fair to good Alcott Louisa Rose in Bloom Whitman Publishing Company $15 poor Alcott Lousia Little Women Juvenile Productions $5 fair to good with d/c Alcott Louisa An Old-Fashion Girl Donohue $10 poor to fair Alcott Louisa Little Women Saalfield $18 fair Alger Horatio In a New World M. A. Donohue $12 fair Allen Hervey Anthony Adverse Farrar and Rinehart Inc. $115 fair to good Angel Henry Practical Plane and Solid Geomerty William Collins, Sons $5 fair Appleton Victor Tom Swift and His Giant Robot Grosset & Dunlap $5 good Aquith & Bigland C. -

Complete Credits

Jerome Leroy CREDITS Awards Golden Lotus Awards / Vietnam Best Composer “The Housemaid: Cô Hàu Gái” Film Festival (2017) Hollywood Intl. Independent Best Score “Qi – The Documentary” Documentary Awards (2017) Jerry Goldsmith Awards (2017) Best Music: Short Film “Charlie’s Supersonic Glider” (nomination) Maverick Movie Awards (2016) Best Music: Feature “A Better Place” (nomination) Lyon Intnl. Film Festival (2016) Best Music (nomination) “A Better Place” Feature Films Killers Within Two Joker Films Paul Bushe & Brian O’Neill, dir. The Housemaid: Cô Hàu Gái HK Films Timothy Bui, prod.; Derek Nguyen, dir. A Better Place Digital Jungle Pictures Dennis Ho, prod. & dir. The Throwaways The Combine Jeremy Renner, Don Handfield, Timothy Bui, prod.; Tony Bui, dir. After Ever After AEA Rakesh Kumar, prod. & dir. #iKllr Kaleidoscope Film Distribution Jeffrey Coghlan, prod. & dir. The Mistover Tale Mistover Harry Tappan Heher, prod. & dir. A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Mandate Pictures / Greg Shapiro, prod., Todd Christmas New Line Cinema Strauss-Schulson, dir. (additional composer) Jerome Leroy • [email protected] • (310) 804-7210 • Page 1! The Hunger Games Lionsgate Nina Jacobson, Jon Kilik, prods.; (additional music programming) Gary Ross, dir. The Tale of Despereaux Universal Pictures Gary Ross, prod.; Sam Fell, Rob (music programming) Stevenhagen, dir. 50 to 1 Ten Furlongs Jim Wilson, prod. & dir. (additional composer) Touchback Freedom Films Carissa Buffel, Brian Presley, (additional composer) prods.; Don Handfield, dir. To Have and To Hold Enthuse Entertainment Barbara Divisek, prod.; Ray (additional composer) Bengston, dir. Alone Yet Not Alone Enthuse Entertainment Barbara Divisek, prod.; Ray (additional composer) Bengston, dir. The Liberator Produccionnes Insurgentes Jose Luis Escolar, prod.; Alberto (additional arranger) Arvelo, dir. -

The Lab Notebook

Thomas Edison National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The Lab Notebook Upcoming Exhibits Will Focus on the Origins of Recorded Sound A new exhibit is coming soon to Building 5 that highlights the work of Thomas Edison’s predecessors in the effort to record sound. The exhibit, accompanied by a detailed web presentation, will explore the work of two French scientists who were pioneers in the field of acoustics. In 1857 Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented what he called the phonautograph, a device that traced an image of speech on a glass coated with lampblack, producing a phonautogram. He later changed the recording apparatus to a rotating cylinder and joined with instrument makers to com- mercialize the device. A second Frenchman, Charles Cros, drew inspiration from the telephone and its pair of diaphragms—one that received the speaker’s voice and the second that reconstituted it for the listener. Cros suggested a means of driving a second diaphragm from the tracings of a phonauto- gram, thereby reproducing previously-recorded sound waves. In other words, he conceived of playing back recorded sound. His device was called a paléophone, although he never built one. Despite that, today the French celebrate Cros as the inventor of sound reproduction. Three replicas that will be on display. From left: Scott’s phonautograph, an Edison disc phonograph, and Edison’s 1877 phonograph. Conservation Continues at the Park Workers remove the light The Renova/PARS Environ- fixture outside the front mental Group surveys the door of the Glenmont chemicals in Edison’s desk and home. -

Painting En Abyme: Tracing the Uses of Painting in New Hollywood Cinema

PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA By MICHELLE LYNN RINARD Bachelor of Arts in Art History Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2015 PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Thesis Approved: Dr. Louise Siddons Thesis Adviser Dr. Jeff Menne Dr. Rebecca Brienen ii Name: MICHELLE L. RINARD Date of Degree: MAY 2015 Title of Study: PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Major Field: ART HISTORY Abstract: In the period of the New Hollywood in cinema, four directors created films that incorporated paintings and artworks within their scenes: Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967); John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966); Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971); and Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). In four close readings, I demonstrate that these filmmakers incorporated painting to contribute to the emotions and narrative, to reflect the institutional power or ideological positions of characters and organizations, and as cultural or anti-cultural capital. The incorporation of painting in film creates a mise en abyme, doubling the forms and meanings of art within the film medium. The use of painting in cinema in the period between 1966 and 1978 is characteristic of an artistic trend in New Hollywood filmmaking. Earlier uses of art in film were overwhelmingly narrative and diegetic, while in New Hollywood film it becomes a mode of editorializing and extra diegetic commentary. -

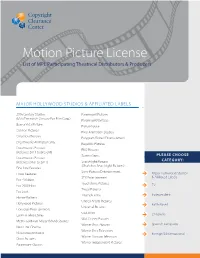

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Visions of Electric Media Electric of Visions

TELEVISUAL CULTURE Roberts Visions of Electric Media Ivy Roberts Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Visions of Electric Media Televisual Culture Televisual culture encompasses and crosses all aspects of television – past, current and future – from its experiential dimensions to its aesthetic strategies, from its technological developments to its crossmedial extensions. The ‘televisual’ names a condition of transformation that is altering the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. Shifts in production practices, consumption circuits, technologies of distribution and access, and the aesthetic qualities of televisual texts foreground the dynamic place of television in the contemporary media landscape. They demand that we revisit concepts such as liveness, media event, audiences and broadcasting, but also that we theorize new concepts to meet the rapidly changing conditions of the televisual. The series aims at seriously analyzing both the contemporary specificity of the televisual and the challenges uncovered by new developments in technology and theory in an age in which digitization and convergence are redrawing the boundaries of media. Series editors Sudeep Dasgupta, Joke Hermes, Misha Kavka, Jaap Kooijman, Markus Stauff Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Ivy Roberts Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: ‘Professor Goaheadison’s Latest,’ Fun, 3 July 1889, 6. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden -

Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think and Why It Matters

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters Amanda Daily Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Daily, Amanda, "Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2230. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2230 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Claremont McKenna College Why Hollywood Isn’t As Liberal As We Think And Why It Matters Submitted to Professor Jon Shields by Amanda Daily for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 April 29, 2019 2 3 Abstract Hollywood has long had a reputation as a liberal institution. Especially in 2019, it is viewed as a highly polarized sector of society sometimes hostile to those on the right side of the aisle. But just because the majority of those who work in Hollywood are liberal, that doesn’t necessarily mean our entertainment follows suit. I argue in my thesis that entertainment in Hollywood is far less partisan than people think it is and moreover, that our entertainment represents plenty of conservative themes and ideas. In doing so, I look at a combination of markets and artistic demands that restrain the politics of those in the entertainment industry and even create space for more conservative productions. Although normally art and markets are thought to be in tension with one another, in this case, they conspire to make our entertainment less one-sided politically. -

The Last Days of Night

FEATURE CLE: THE LAST DAYS OF NIGHT CLE Credit: 1.0 Thursday, June 14, 2018 1:25 p.m. - 2:25 p.m. Heritage East and Center Lexington Convention Center Lexington, Kentucky A NOTE CONCERNING THE PROGRAM MATERIALS The materials included in this Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education handbook are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of this Kentucky Bar Association CLE program disclaim liability therefore. Attorneys using these materials, or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. Printed by: Evolution Creative Solutions 7107 Shona Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45237 Kentucky Bar Association TABLE OF CONTENTS The Presenter .................................................................................................................. i The War of the Currents: Examining the History Behind The Last Days of Night .................................................................................................... 1 AC/DC: The Two Currents