CHINA's ESTABLISHED INTELLECTUALS: a Sociological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Asia's Energy Security

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #68 | november 2017 asia’s energy security and China’s Belt and Road Initiative By Erica Downs, Mikkal E. Herberg, Michael Kugelman, Christopher Len, and Kaho Yu cover 2 NBR Board of Directors Charles W. Brady Ryo Kubota Matt Salmon (Chairman) Chairman, President, and CEO Vice President of Government Affairs Chairman Emeritus Acucela Inc. Arizona State University Invesco LLC Quentin W. Kuhrau Gordon Smith John V. Rindlaub Chief Executive Officer Chief Operating Officer (Vice Chairman and Treasurer) Unico Properties LLC Exact Staff, Inc. President, Asia Pacific Wells Fargo Regina Mayor Scott Stoll Principal, Global Sector Head and U.S. Partner George Davidson National Sector Leader of Energy and Ernst & Young LLP (Vice Chairman) Natural Resources Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific KPMG LLP David K.Y. Tang HSBC Holdings plc (Ret.) Managing Partner, Asia Melody Meyer K&L Gates LLP George F. Russell Jr. President (Chairman Emeritus) Melody Meyer Energy LLC Chairman Emeritus Honorary Directors Russell Investments Joseph M. Naylor Vice President of Policy, Government Lawrence W. Clarkson Dennis Blair and Public Affairs Senior Vice President Chairman Chevron Corporation The Boeing Company (Ret.) Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA U.S. Navy (Ret.) C. Michael Petters Thomas E. Fisher President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President Maria Livanos Cattaui Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. Unocal Corporation (Ret.) Secretary General (Ret.) International Chamber of Commerce Kenneth B. Pyle Joachim Kempin Professor; Founding President Senior Vice President Norman D. Dicks University of Washington; NBR Microsoft Corporation (Ret.) Senior Policy Advisor Van Ness Feldman LLP Jonathan Roberts Clark S. -

Adaptive Fuzzy Pid Controller's Application in Constant Pressure Water Supply System

2010 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2010) Hangzhou, China 4-6 December 2010 Pages 1-774 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1076H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-7616-9 1 / 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS ADAPTIVE FUZZY PID CONTROLLER'S APPLICATION IN CONSTANT PRESSURE WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Xiao Zhi-Huai, Cao Yu ZengBing APPLICATION OF OPC INTERFACE TECHNOLOGY IN SHEARER REMOTE MONITORING SYSTEM ...............................5 Ke Niu, Zhongbin Wang, Jun Liu, Wenchuan Zhu PASSIVITY-BASED CONTROL STRATEGIES OF DOUBLY FED INDUCTION WIND POWER GENERATOR SYSTEMS.................................................................................................................................................................................9 Qian Ping, Xu Bing EXECUTIVE CONTROL OF MULTI-CHANNEL OPERATION IN SEISMIC DATA PROCESSING SYSTEM..........................14 Li Tao, Hu Guangmin, Zhao Taiyin, Li Lei URBAN VEGETATION COVERAGE INFORMATION EXTRACTION BASED ON IMPROVED LINEAR SPECTRAL MIXTURE MODE.....................................................................................................................................................................18 GUO Zhi-qiang, PENG Dao-li, WU Jian, GUO Zhi-qiang ECOLOGICAL RISKS ASSESSMENTS OF HEAVY METAL CONTAMINATIONS IN THE YANCHENG RED-CROWN CRANE NATIONAL NATURE RESERVE BY SUPPORT -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

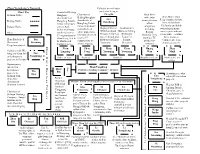

Zhou Yongkang's Network

Zhou Yongkang’s Network Colluded on real estate Chart Key Controlled Beijing project w/ Feng in Sichuan Native Honghan; Chairman of Chengdu Zhou Bin’s Zhan Minli, Zhou shareholder of Beijing Honghan; wife, who Sun Feng’s mother-in-law, Beijing Native Hongfeng Potash shareholder of managed many Jiancheng lives in Southern mines in Sichuan, Hongfeng Potash of his California and holds Jiangsu Native owned Audi mines in Sichuan; companies, ` Deputy Chief of Established A dealer in Jiangsu; controlled real including ownership in many— Wuxi Land and Business Selling Other involved in over estate projects in Beijing some reports indicate Resources Bureau; Wuliangye at least nine—of Zhou 37 corporations w/ Chengdu involved Zhongxu; Also travelled back and Liquor in Bin’s business Zhou Feng; tied to in over 37 started a TV Zhou Bin helped Dai forth to visit Zhou Jiangsu; ventures; she is an Li Hualin and corporations w/ production Dai secure Xiaoming Yonakang Deceased American citizen Kunlun Energy Zhou Lingying company Pengzhou project Zhou Bin’s Business Partners Business Bin’s Zhou Zhou Zhou Zhou Zhou Huang Zhan Colluded with Wu Lingying Feng Yuanqing Yuanxing Wan Minli Guo Bing and Zhou Bin Yongxiang on hydropower Sister-in-Law Nephew Brothers Daughter-in-Law Mother-in-Law projects in Sichuan of Son Businessman, invested in Son Zhou Yongkang hydropower Zhou Politburo Standing Committee Member Wu Bin projects in Bing A soothsayer, who Cao Sichuan with advised Li on urban Zhou Bin; Former Yongzheng projects; chairman of Chairman Major Zhou Surrogates/Secretaries in Sichuan Zhongxu Limited of Beijing Head of PSB in Zhongxu Guo Li Li Wu Jinjiang District, Yangguang Yongxiang Chongxi Chuncheng Tao Chengdu, gave Li Chairman of Petroleum Sichuan Hanlong illegal passports Liu and Natural Former Vice- Former Deputy Mayor of Chengdu; Company. -

Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies

Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies Volume 8, Issue 1, January 2018 ISSN 2048-0601 Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies This e-journal is a peer-reviewed publication produced by the British Association for Chinese Studies (BACS). It is intended as a service to the academic community designed to encourage the production and dissemination of high quality research to an international audience. It publishes research falling within BACS’ remit, which is broadly interpreted to include China, and the Chinese diaspora, from its earliest history to contemporary times, and spanning the disciplines of the arts, humanities and social sciences. Editors Sarah Dauncey (University of Nottingham) Gerda Wielander (University of Westminster) Sub-Editor Scott Pacey (University of Nottingham) Editorial Board Tim Barrett (School of Oriental and African Studies) Jane Duckett (University of Glasgow) Harriet Evans (University of Westminster) Stephanie Hemelryk Donald (University of New South Wales) Stephan Feuchtwang (London School of Economics) Natascha Gentz (University of Edinburgh) Rana Mitter (University of Oxford) Qian Suoqiao (University of Newcastle) Caroline Rose (University of Leeds) Naomi Standen (University of Birmingham) Yao Shujie (University of Nottingham) Journal of the British Association for Chinese Studies Volume 8, Issue 1, January 2018 Contents Editors’ Introduction iv Articles Premarital Abortion—What is the Harm? The Responsibilisation of 1 Women’s Pregnancy Among China’s “Privileged” Daughters Kailing Xie Encompassing the Horse: Analogy, Category, and Scale in the Yijing 32 William Matthews The Favourable Partner: An Analysis of Lianhe Zaobao’s 62 Representation of China in Southeast Asia Daniel R. Hammond Free Trade, Yes; Ideology, Not So Much: The UK’s Shifting China Policy 92 2010-16 Scott A.W. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure -

Final Program of CCC2020

第三十九届中国控制会议 The 39th Chinese Control Conference 程序册 Final Program 主办单位 中国自动化学会控制理论专业委员会 中国自动化学会 中国系统工程学会 承办单位 东北大学 CCC2020 Sponsoring Organizations Technical Committee on Control Theory, Chinese Association of Automation Chinese Association of Automation Systems Engineering Society of China Northeastern University, China 2020 年 7 月 27-29 日,中国·沈阳 July 27-29, 2020, Shenyang, China Proceedings of CCC2020 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2040A -USB ISBN: 978-988-15639-9-6 CCC2020 Copyright and Reprint Permission: This material is permitted for personal use. For any other copying, reprint, republication or redistribution permission, please contact TCCT Secretariat, No. 55 Zhongguancun East Road, Beijing 100190, P. R. China. All rights reserved. Copyright@2020 by TCCT. 目录 (Contents) 目录 (Contents) ................................................................................................................................................... i 欢迎辞 (Welcome Address) ................................................................................................................................1 组织机构 (Conference Committees) ...................................................................................................................4 重要信息 (Important Information) ....................................................................................................................11 口头报告与张贴报告要求 (Instruction for Oral and Poster Presentations) .....................................................12 大会报告 (Plenary Lectures).............................................................................................................................14