Treatment of Equine Sarcoid with the Mistletoe Extract ISCADOR® P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEI Regulations for Equestrian Events at the Olympic Games

FEI Fédération Equestre Internationale FEI Regulations for Equestrian Events at the Olympic Games 24th Edition, Effective for the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 23 July-8 August 2021 Fédération Equestre Internationale t +41 21 310 47 47 HM King Hussein I Building f +41 21 310 47 60 Chemin de la Joliette 8 www.fei.org 1006 Lausanne Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Copyright © 2018 Fédération Equestre Internationale 7 December 2018 Updated on 21 December 2018 Updated on 30 December 2018 Updated on 18 April 2019 Updated on 3 October 2019 Updated on 24 June 2020 Updated on 16 June 2021 FEI Regulations for Equestrian Events Tokyo (JPN) 2020 Olympic Games TABLE OF CONTENTS THE FEI CODE OF CONDUCT FOR THE WELFARE OF THE HORSE .................................. 4 CHAPTER I GENERAL .................................................................................................. 6 ARTICLE 600 – INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 6 ARTICLE 601 –COMPETITIONS .................................................................................................... 6 ARTICLE 602 – COMPETITION SCHEDULE .................................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 603 – CLASSIFICATION, MEDALS & PRIZES..................................................................... 7 ARTICLE 604 – QUOTA .............................................................................................................. 8 ARTICLE 605 - AP ALTERNATE ATHLETES, RESERVE HORSES, -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices

1 Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices 2 Appendix 1. Full breed list, listed alphabetically. Breeds searched (* denotes those identified with inherited disorders) # Breed # Breed # Breed # Breed 1 Ab Abyssinian 31 BF Black Forest 61 Dul Dülmen Pony 91 HP Highland Pony* 2 Ak Akhal Teke 32 Boe Boer 62 DD Dutch Draft 92 Hok Hokkaido 3 Al Albanian 33 Bre Breton* 63 DW Dutch Warmblood 93 Hol Holsteiner* 4 Alt Altai 34 Buc Buckskin 64 EB East Bulgarian 94 Huc Hucul 5 ACD American Cream Draft 35 Bud Budyonny 65 Egy Egyptian 95 HW Hungarian Warmblood 6 ACW American Creme and White 36 By Byelorussian Harness 66 EP Eriskay Pony 96 Ice Icelandic* 7 AWP American Walking Pony 37 Cam Camargue* 67 EN Estonian Native 97 Io Iomud 8 And Andalusian* 38 Camp Campolina 68 ExP Exmoor Pony 98 ID Irish Draught 9 Anv Andravida 39 Can Canadian 69 Fae Faeroes Pony 99 Jin Jinzhou 10 A-K Anglo-Kabarda 40 Car Carthusian 70 Fa Falabella* 100 Jut Jutland 11 Ap Appaloosa* 41 Cas Caspian 71 FP Fell Pony* 101 Kab Kabarda 12 Arp Araappaloosa 42 Cay Cayuse 72 Fin Finnhorse* 102 Kar Karabair 13 A Arabian / Arab* 43 Ch Cheju 73 Fl Fleuve 103 Kara Karabakh 14 Ard Ardennes 44 CC Chilean Corralero 74 Fo Fouta 104 Kaz Kazakh 15 AC Argentine Criollo 45 CP Chincoteague Pony 75 Fr Frederiksborg 105 KPB Kerry Bog Pony 16 Ast Asturian 46 CB Cleveland Bay 76 Fb Freiberger* 106 KM Kiger Mustang 17 AB Australian Brumby 47 Cly Clydesdale* 77 FS French Saddlebred 107 KP Kirdi Pony 18 ASH Australian Stock Horse 48 CN Cob Normand* 78 FT French Trotter 108 KF Kisber Felver 19 Az Azteca -

Eric Lamaze in the in Good Standing

THE WARM-UP RING The Official News of the Jumping Committee September 2019, Volume 15, Issue 9 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR IN THIS ISSUE their phone – whatever works! – to ensure that they have all their ducks in a row for 2020 as follows: On The Show Scene • Join your National Federation Michelle C. Dunn (EC) and purchase any other Canada Second in BMO Nations’ memberships you may need to count Cup at Spruce Meadows ‘Masters’ points early in the year (provincial Royal Horse Show’s Opening hunter/jumper associations, CET Medal program registration, etc.). Weekend Showcases Canadian Double check that payment has gone Championships through and that you are a member Vote NOW for Eric Lamaze in the in good standing. • Make a decision early if you wish FEI Awards to request a change of province for BMO Introduces the Ian Millar your CET Medal Regional Final. The deadline is August 15 of each year Legacy Award with no exceptions. Thank you to our NAYC Sponsors! Fall is officially upon us, and the annual The Jumping Committee does its best to countdown to the Royal Agricultural Winter grant requests for a change of province so Get Your Jump Canada Hall of Fair is underway. With it comes the four that riders are able to compete in the region Fame Tickets! CET Medal Regional Finals which, in turn, that is most suitable for them. However, it Richard Mongeau Departs as Chief determine the riders who qualify for the cannot grant exceptions. It is clearly written Running Fox CET Medal National Final at in the Rulebook. -

1 Nature of Horse Breeds

1 Nature of Horse Breeds The horse captures our imagination because of its beauty, power and, most of all, its personality. Today, we encounter a wide array of horse breeds, developed for diverse purposes. Much of this diversity did not exist at the time of domestication of the horse, 5500 years ago (Chapter 2). Modern breeds were developed through genetic selection and based on the variety of uses of horses during the advance of civilization. Domestication of the horse revolutionized civilization. A rider could go farther and faster than people had ever gone before. Horses provided power to till more land and move heavier loads. Any sort of horse could provide these benefits, as long as it could be domesticated. However, over time people became more discern- ing about the characteristics of their horses. The intuitive and genetic principle that “like begat like” led people to choose the best horses as breeding stock. At the same time, people in different parts of the world used different criteria when select- ing horses. The horses were raised in different climates, fed different rations, exposed to different infectious diseases, and asked to do different types of work. Genetic differences could and did have a large impact on these traits. Over time, selection led to the creation of diverse types of horse around the world. We use a variety of terms to describe the genetic diversity among groups of animals, both to distinguish horses from other animals and examine differences among the different types of horses. Those terms include genus, species, popula- tion, landrace, and breed. -

Sedation and Anesthesia in Military Horses and Mules. Review And

S S E E L L C C Sedation and Anesthesia in Military Horses and Mules. I I T T R R Review and Use in the Swiss Armed Forces. A A By S. MONTAVON∑, C. BAUSSIERE∏, C. SCHMOCKER∏ and M. STUCKI∏. Switzerland Stéphane MONTAVON Colonel Stéphane MONTAVON has been the Chief Veterinary Officer of the Swiss Army since 2003. He obtained his veterinary degree and completed his doctoral thesis at the Vetsuisse veterinary faculty in Bern. He was successively head of clinic at the Federal Army Horse Reserve in Bern, head of clinic at the National Stud in Avenches, resident and clinician at the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at UC Davis (USA). He is a long-time member of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP). He specializes in equine sports medicine and is an excellent rider and an official veterinarian of the (FEI) Federation Equestre Internationale. RESUME Sédation et anesthésie chez les chevaux et mules militaires. Revue et utilisation dans l'armée suisse. L'armée suisse utilise depuis plus de 100 ans différents types de chevaux pour des missions spéciales. Trois races sont utilisées : Les chevaux de race demi-sang suisse pour l'équitation, les chevaux Franches-Montagnes et les mulets comme « chevaux de bât » pour le transport. Cet article passe en revue les substances, dosages et voies d'administration qui permettent de réaliser des sédations et des anesthésies simples chez le cheval comme sur le mulet, dans le terrain et dans un contexte militaire. Cette contribution est aussi destinée aux autres armées qui utilisent des mulets dans la mesure où la littérature n'est pas très riche dans ce domaine. -

International Jumping Festival Grand Prix Field Wednesday, September 18, 2019

INTERNATIONAL JUMPING FESTIVAL GRAND PRIX FIELD WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2019 *Horses showing in the USEF Talent Search Finals may only show in class #229 1.15m Jumpers on Wednesday. 8:00 a.m. – Classes #221. 1.00m Jumpers Table II, Sec. 2(d) 11:00 a.m. – Classes #229. 1.15m Jumpers Table II, Sec. 2(d)* *Open water will be an option 1:00 p.m. – Class #250. 1.20m Jumpers Table II, Sec. 2(d) 3:15 p.m. – Class #305. 1.40m Jumpers Table II, Sec. 1 Cancelled – Class #309. 1.45m Jumpers Table II, Sec. 1 [Finish: 3:50 p.m.] Class #221 - 1.00m Jumpers # HORSE RIDER ELVIS 284 HOLSTEINER, 2010, G, 1 542 LARIMAR x WINTERA JAVIER ABAD 8:00:00 CANTINA TRAKEHNER, 2013, G, 2 262 UNKNOWN x UNKNOWN JOHN BRAGG 8:02:30 BOUJEE SELLE FRANCAIS, 2010, G, 3 464 UNKNOWN x UNKNOWN JOSH MADGWICK 8:05:00 CAMPITELLO 5 HANOVERIAN, 2007, G, 4 581 CATOKI x GINA EMMA CATHERINE REICHOW 8:07:30 NEWTON HOLSTEINER, 2013, G, 5 326 NARRADO x SEESTERMUEHE JENNY KARAZISSIS 8:10:00 KANNAN LOVER WARMBLOOD, 2002, G, 6 232 KANNAN x PENNY LOVER EMILY ESAU WILLIAMS 8:12:30 MLB CLAIR DE LUNE UNKNOWN, 2013, M, 7 379 INDOCTRO x ALLURE MICHELLE PARKER 8:15:00 CAZZ C DUTCH WARMBLOOD, 2007, 8 136 G, UNKNOWN x UNKNOWN JACKIE LEFAVE 8:17:30 DEBUT HANOVERIAN, 2011, G, 9 532 DAMSEY x GENOVEVA LEXI WEDEMEYER 8:20:00 ANAKIN DUTCH WARMBLOOD, 2012, G, VAN HELSING x DYTHERA 10 295 H BROOKE MOSTMAN 8:22:30 S & L TECHNICOLOR DUTCH WARMBLOOD, 2006, 11 393 G, CHIN CHIN x UNKNOWN ALYSIA LYNCH-SHERARD 8:25:00 HANDS UP DUTCH WARMBLOOD, 2012, 12 383 G, INDOCTRO x SUZANNA LAUREN KATZENELLENBOGEN 8:27:30 -

Survey of Risk Factors and Genetic Characterization of Ewe Neck in a World Population of Pura Raza Español Horses

animals Article Survey of Risk Factors and Genetic Characterization of Ewe Neck in a World Population of Pura Raza Español Horses María Ripolles 1, María J. Sánchez-Guerrero 1,2,*, Davinia I. Perdomo-González 1 , Pedro Azor 1 and Mercedes Valera 1 1 Department of Agro-Forestry Sciences, ETSIA, University of Seville, Carretera de Utrera Km 1, 41013 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (D.I.P.-G.); [email protected] (P.A.); [email protected] (M.V.) 2 Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry Engineering, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Carretera de Utrera Km 1, 41013 Sevilla, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-9-5448-6461 Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 27 September 2020; Published: 1 October 2020 Simple Summary: Ewe Neck is a common morphological defect of the Pura Raza Español (PRE) population, which seriously affects the horse’s development. In this PRE population (35,267 PRE), a total of 9693 animals (27.12% of total) was Ewe Neck-affected. It has been demonstrated that genetic and risk factors (sex, age, geographical area, coat color, and stud size) are involved, being more prevalent in the males, 4–7 years old, chestnut coat, from small studs (less than 5 mares), and raised in North America. The morphological traits height at chest, length of back, head-neck junction, and bottom neck-body junction and the body indices, head index, and thoracic index were those most closely related with the appearance of this morphological defect. The additional genetic base of Ewe Neck in PRE, which presents low-moderate heritability (h2: 0.23–0.34), shows that the prevalence of this defect could be effectively reduced by genetic selection. -

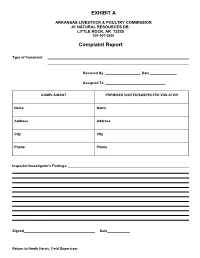

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

Highlights from Proposed New Irish Sport Horse Breeding Policy 2010 - 2015

Highlights from Proposed New Irish Sport Horse Breeding Policy 2010 - 2015 Mo Chroi (ISH) – 1997 by Cruising (ISH) out of Into The Blue (ISH) by Mister Lord (TB), bred by Claire McDonnell, Ballymoney Park Stud, Kilbride, Co. Wicklow. Rider: Capt. David O’ Brien (IRL). 1 A recent study carried out by UCD estimated that: • The Sport Horse Industry is worth €400 million annually to the Irish economy • It provides employment to approx. 20,000 individuals on a full-time and part-time basis • There are 53,000 participants in the equestrian sector • The Sport Horse population is approx. 110,000 in Ireland, with a mare herd of approx. 12,000 which produces approx. 9,500 foals annually Breeding Statistics for Foals registered in IHR in 2008 Number of IHR breeders 12,000 Total number of foals registered in IHR 9,536 Average number of foals per breeder 2 Maximum number of foals per breeder 27 Total number of stallions registered in IHR 1,640 Average number of foals per sire 10 Maximum number of foals per sire 204 2 WBFSH Rankings WBFSH World Ranking List by Studbook up to May 2009 Show Jumping Eventing 1 Français du Cheval Selle Français (SF) 1 Irish Sport Horse (ISH) 2 Koninklijk Warmblood Paardenstamboek 2 Français du Cheval Selle Français (SF) Nederland (KWPN) 3 Verband der Züchter des Holsteiner 3 Hannoveraner Verband e.v. (HANN) Pferdes (HOLST) 4 Belgisch Warmbloedpaard (BWP) 4 Westfälisches Pferdestammbuch (WESTF) 5 Westfälisches Pferdestammbuch (WESTF) 5 Koninklijk Warmblood Paardenstamboek Nederland (KWPN) 6 Hannoveraner Verband e.v. (HANN) -

Statutes of the Verband Der Züchter Des Holsteiner Pferdes E. V

Statutes of the Verband der Züchter des Holsteiner Pferdes e. V. Version as of 05/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS page I. Constitution A. General § 1 Name, Registered Office, Legal Nature 1 § 2 Scope of Function 1 § 3 Area of Activity 2 B. Membership § 4 Members 2 § 5 Acquiring Membership 3 § 6 Termination of Membership 3 § 7 Members’ Rights 4 § 8 a Obligations of Members 5 § 8 b Rights and Obligations of the 6 Association C. Bodies of the Association § 9 Bodies 7 § 10 Board of Directions 7 § 10a Advisory Board 9 § 11 Assembly of Delegates 9 D. Breeding Committee, Stal- § 12 Area of Activity 12 lion Owners’ Delegation and Breeding Committees § 13 Breeding Committee/Stallion Owners’ 12 Delegation § 14 Stallion Licensing Committee/ Objec- 13 tion Committee § 15 Inspection and Registration Committee 16 E. Data protection § 16 Data Protection 17 F. Management § 17 Managing Directors 18 § 18 Invoice and Cash Auditing 19 Version as of 05/2019 G. Arbitration § 19 Arbitration 19 H. Dissolution § 20 Dissolution 21 II. Breeding § 21 Preamble 22 Programme § 22 Breeding Goal 23 I. External Appearance 23 II. Movement 24 III. Inner Traits/ 25 Performance Aptitude/ Health IV. Summary 25 § 23 Traits of the Treed and Breeding 26 Methods § 24 Limits on the Use of Stallions 28 § 25 Registration of Horses from Other 28 Breeding Populations § 26 Selection Criteria 29 § 27 Foal Inspections 35 § 28 Awards for Mares 35 § 29 Licensing of Stallions 36 § 30 Structure of the Breed Registry 40 § 31 Registration of Stallions 41 § 32 Artifical Insemination 44 § 33 Embryo Transfer -

Canadian Show Jumping Team

CANADIAN SHOW JUMPING TEAM 2020 MEDIA GUIDE Introduction The Canadian Show Jumping Team Media Guide is offered to all mainstream and specialized media as a means of introducing our top athletes and offering up-to-date information on their most recent accomplishments. All National Team Program athletes forming the 2020 Canadian Show Jumping Team are profiled, allowing easy access to statistics, background information, horse details and competition results for each athlete. We have also included additional Canadian Show Jumping Team information, such as past major games results. The 2020 Canadian Show Jumping Team Media Guide is proudly produced by the Jumping Committee of Equestrian Canada, the national federation responsible for equestrian sport in Canada. Table of Contents: Introduction 2 2020 Jumping National Team Program Athletes 3 Athlete Profiles 4 Chef d’équipe Mark Laskin Profile 21 Major Games Past Results 22 Acknowledgements: For further information, contact: Editor Karen Hendry-Ouellette Jennifer Ward Manager of Sport - Jumping Starting Gate Communications Inc. Equestrian Canada Phone (613) 287-1515 ext. 102 Layout & Production [email protected] Starting Gate Communications Inc. Photographers Equestrian Canada Arnd Bronkhorst Photography 11 Hines Road ESI Photography Suite 201 Cara Grimshaw Kanata, ON R&B Presse K2K 2X1 Sportfot CANADA Starting Gate Communications Phone (613) 287-1515 Toll Free 1 (866) 282-8395 Fax (613) 248-3484 On the Cover: www.equestrian.ca Beth Underhill and Count Me In 2019 Canadian Show Jumping Champions by Starting Gate Communications 2020 Jumping National Team Program Athletes The following horse-and-rider combinations have been named to the 2020 Jumping National Team Program based on their 2019 results: A Squad 1 Nicole Walker ......................................................................