Fr Lorenzo Book Fa.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lacor Hospital Visitor Resource Pack

Lacor Hospital Visitor Resource Pack The best treatment possible, to the highest number of people, at the lowest cost possible - Piero Corti Index Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 St. Mary’s Hospital Lacor ..................................................................... 2 Travelling to Lacor ................................................................................ 4 Location & Weather ............................................................................................................... 4 Travel Health ......................................................................................................................... 5 Pre-trip vaccinations ....................................................................................................... 5 Malaria Prophylaxis ......................................................................................................... 5 Visa ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Mandatory Professional Council Registration ................................................................ 6 Required documentation for application to UMDPC: .................................................. 7 Insurance ............................................................................................................................... 7 Travel & Connections ........................................................................................................... -

African Mission Annual Report 2018-2019

African Mission Annual Report 2018-2019 1 The Aim of African Mission is “To fight disease and poverty in Africa by supporting educational & medical projects”. Background: African Mission was started in 2003 to support the work of Dr Ray Towey MB ChB FRCA. Dr Towey left his post as a Consultant Anaesthetist in Guys Hospital, London to work in Africa and since 1993 has dedicated his life to the improvement of health care for the poor in Africa. He has worked as an Anaesthetist in rural hospitals in Nigeria and Tanzania and since 2002 in St Mary’s Hospital, Gulu, Uganda. Dr. Towey has been in Uganda for 17 years and has been involved in the training of anaesthetic officers, nurses, and medical students over that time. He is now a part time volunteer and is focusing in the development of the intensive care ward, measuring the outcomes of specific diseases amenable to intensive care in rural Africa, sustaining the equipment for respiratory support, working to improve intensive care nursing and researching the data to indicate the effectiveness and sustainability of appropriate inexpensive intensive care in rural sub-Saharan Africa. In July 2009 following a visit to Zimbabwe by Nannette & Dr Towey, African Mission decided to expand its work to include supporting projects based in Zimbabwe. The main Zimbabwean project supported is Fatima Mission. Fatima Mission is a very large mission (600 sq miles in size) based in rural Zimbabwe, approximately 130 miles north of Bulawayo and a similar distance south of Victoria Falls. Practically everyone living within Fatima Mission’s boundaries are poor subsistence farmers. -

La Fondazione Piero E Lucille Corti Onlus 33

Lacor Hospital Molto più di un ospedale “Non far parte della soluzione significa far parte del problema” Lucille Teasdale Corti Fondazione Piero e Lucille Corti Onlus P.zza Velasca 6, 20122 Milano Tel.: +39 02 49.52.40.96 Fax: +39 02 80.54.728 [email protected] - fondazionecorti.it Per le fotografie si ringrazia Mauro Fermariello Indice Fate parte con noi di questa storia 5 Piero Corti e Lucille Teasdale 6 Il Lacor Hospital 9 Un grande polo ospedaliero 11 Cambia lo scenario: dalla guerra alla pace 12 Un grande polo per la formazione 16 Molto più di un semplice ospedale 19 I costi e la loro copertura 21 L’Uganda 23 La sfida: finita la guerra, bisogna vincere la pace 27 Curare le malattie è lottare contro la povertà 27 Punti di forza del Lacor Hospital 29 Virus letale 31 La Fondazione Piero e Lucille Corti Onlus 33 Come aiutarci 35 Donazioni 37 I nostri libri e filmati 38-39 6 Fate parte con noi di questa storia C’era una volta... Nel 1959, nella savana del nord Uganda, i Missionari Comboniani fondano, per conto della Diocesi di Gulu, un piccolo ospedale missionario. In 50 anni, l’ospe- dale è stato trasformato in un grande polo ospedaliero ed è oggi sinonimo di speranza per centinaia di migliaia di persone che ogni anno vi arrivano, anche da molto lontano. Questo è stato possibile grazie all’ispirazione, al lavoro e alla tenacia di due medici, i coniugi Piero e Lucille Corti, che per oltre trent’anni han- no sviluppato l’ospedale, e ai molti colleghi italiani e ugandesi che a loro si sono affiancati e succeduti, nonostante le sfide imposte da un trentennio di guerre, di povertà estrema e terribili epidemie. -

Global Engagement Studies Institute

GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT STUDIES INSTITUTE GESI PRE-DEPARTURE PACKET SUMMER 2019 | UGANDA Table of Contents PART I About GESI Welcome (3) Program Information (4) Program Partners (5) Program Details Pre-Departure Academic Information (6) In-Country Academic Information (7) Final Summit Academic Information (8) Health & Safety (9) Preparation Cultural Adjustment (9) Food for Thought (10) Make the Most of Your Experience (11) When Things Get Tough (12) Works Cited (12) ..... PART II About FSD Letter from FSD (14) About FSD (15-17) Safety Safety (18) Health Preparation (19) Logistics Visas (20) Packing List & FAQs (21-23) Food & Water (24) Communication (25) Money, Flight, Transportation (26-27) Family Homestay (28-29) Personal Account (30) Preparation Cultural Practices at Home & Work (31-32) Race, Sexuality, Gender & Relationships (33-34) Language Guide (35) Film Guides (36) Website & Reading Guides (37) 2 Welcome Dear GESI Student, Welcome to the 13th annual Global Engagement Studies Institute (GESI)! GESI began with the idea and persever- ance of an undergraduate like you. It has since grown from a small experiential-learning program in Uganda exclusively for Northwestern students, into a nationally recognized model that has trained and sent over 650 students from almost 100 colleges and universities to 13 countries for community development work. GESI offers students the unique opportunity to apply their classroom learning toward addressing global chal- lenges. Students will spend their time abroad working with, and learning from, our community partners across the world. Northwestern University provides students with comprehensive preparatory coursework and training, ensures a struc- tured and supported in-country field experience, and facilitates critical post-program reflection. -

Notizie Dal Lacor in UGANDA, PER LA CURA E LO SVILUPPO Poste Italiane Spa – Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale-D.L.353/2003 (Conv

ANNO XIII GIUGNO 2017|N.2 In caso di mancato recapito si prega inviare al CMP Milano Roserio per la restituzione mittente previo pagamento della relativa tariffa resi Notizie Dal Lacor IN UGANDA, PER LA CURA E LO SVILUPPO Poste Italiane Spa – Spedizione in abbonamento postale-D.L.353/2003 (conv. In L. 27/002/2004 n.46) art.1, comma 2 e 3, LO/MI Foto ©Mauro Fermariello Dalla redazione In questo numero Pronti a viaggiare insieme a noi? Vi accompagneremo lungo il tragitto In primo piano compiuto da un letto donato al Lacor. Il suo viaggio comincia da quando 2 Il lungo viaggio di un letto la Fondazione Corti viene scelta come destinatario di una donazione; si avvale poi dell’impegno dei volontari che si occupano della logistica e 4 Dall’Africa infine si mette in cammino, su ruote o via nave, per raggiungere, dopo più Le donne africane sono molto forti! di due mesi, il Nord Uganda. Dall’Italia Ma vi portiamo anche in un viaggio che collega passato e presente. 6 La Fondazione nei ricordi di chi l’ha fatta nascere Le prossime pagine ospitano un contributo di Atim Molinari, medico del Cuamm. Atim è nata al Lacor. Da Lucille, sua madrina, ha ereditato la Sostienici passione per la medicina come missione e per la gente d’Africa. 8 Il tuo aiuto è prezioso E poi ancora un viaggio nel passato, nel 1993, data in cui la Fondazione Corti è stata istituita. Con un occhio al futuro, spiegandovi perché è così prezioso ogni lascito che scegliete di destinarci. -

The Teasdale-Corti Global Health Research Partnership Program

Building Capacity and Transferring Knowledge: The Teasdale-Corti Global Health Research Partnership Program Drs Lucille Teasdale and Piero Corti 2007-01 By Laura Eggertson Whenever television crews showed up at St. Mary’s Hospital Lacor in northern Uganda, Dr Piero Corti would issue his standard instructions: "No white faces," he’d tell the camera operators. "Get the whites out of the shot — they’re only here for a short time. The Ugandans are the ones doing all the work." The attraction for the television crews was the success of Lacor. What began as a 30-bed hospital built by an Italian missionary order grew, over the next 40 years, into a 483-bed institution providing top-quality medical care. Through decades of turmoil spawned by dictatorship and civil war, Corti and his Canadian surgeon wife, Lucille Teasdale, faced down chaos and treated hundreds of thousands of Ugandans. Building Ugandan capacity Throughout their careers, their philosophy was the same one that guided Corti to direct the camera crews to focus on the African faces: empowerment, not charity. They were determined to build capacity and to train Ugandan professionals to care for their own people. "The idea was to get the best possible care to the most people at the least cost," explains Dr Dominique Corti, the couple’s daughter. Today, more than 500-member staff of Lacor are Ugandans. In 2005, the hospital admitted close to 35 000 patients and treated another 250 000 outpatients. An international partnership That philosophy of capacity building has now inspired the Teasdale-Corti Global Health Research Partnership Program. -

Brochure Fondazione Corti

la vita al centro ©Seamus Murphy Al dottor Matthew Lukwiya, brillante medico ugandese, amatissimo eroe del Lacor, e ai dodici dipendenti che, insieme a lui, hanno perso la vita per arginare l’epidemia di Ebola che ha devastato il Nord Uganda nel 2000. Di fronte alla morte di alcuni tra coloro che avevano accettato il suo invito a restare per presidiare l’ospedale e curare i malati di Ebola, Matthew disse: “...nel nostro personale mai una parola di risentimento, di rabbia, di pentimento... sono tutti giovani con davanti sogni e progetti per l’avvenire, eppure si prodigano, rischiando la vita e sacrificandola... Sono un dono che il presente e il futuro dovrà valorizzare “. Testi a cura di Daniela Condorelli, giornalista, responsabile Comunicazione Fondazione Corti Matthew Lukwiya, novembre 2000 Fotografie di Mauro Fermariello, Seamus Murphy. Richard A. Rowe Grafica di copertina: Studio Anastasia Più che un ospedale, un fratello “Il mio nome è Dominique Atim Corti: sono nata in Nord Uganda, al Lacor Hospital di Gulu, oggi tra i più grandi e attrezzati poli ospedalieri non profit dell’Africa Equatoriale. Il Lacor, per me, è molto di più di un ospedale: è un fratello. Era un piccolo ospedale di trenta letti nel mezzo della savana quando, sessant’anni fa, i miei genitori, entrambi medici, l’hanno preso sotto le loro ali. Da allora è cresciuto diventando una cittadella della salute che ogni anno accoglie 250 mila pazienti e vede nascere quasi diecimila bambini. È perché il Lacor continui a dare il meglio ai più vulnerabili che, da 25 anni, esiste la Fondazione Corti, nata per affiancarlo e sostenerlo con risorse e competenze. -

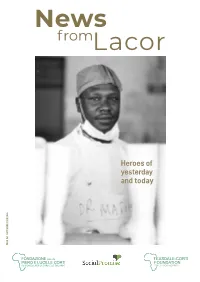

Heroes of Yesterday and Today

News fromLacor Photo: Seamus Murphy - Getty Images Murphy Photo: Seamus Heroes of yesterday and today 2020 | N.4 YEAR XVI NOVEMBER TEASDALE-CORTI FOUNDATION FOR LACOR HOSPITAL EDITORIAL Dr. Venice Omona, Head of the Children's Ward BEING A HERO MEANS... Dear friends, STRUGGLING WITH SCARCE RESOURCES TO TAKE CARE OF PATIENTS just a year ago we were celebrating Lacor’s first 60 years together. though, I am frustrated, as I don’t feel Today we gently tiptoe in your homes, Our doctors, I have done enough. Then I realize to remind you that we are here, that nurses and that the limitations of my country are we keep going, that neither you nor midwives to blame. Limitations in diagnostic, we are alone. at Lacor are heroes. in available treatments, in being The alliance we started in Uganda able to follow up with a patient after many, many years ago, has been They represent an examination. strengthened into a deep friendship. the Africa that And the challenge becomes even During these times that are so full studies, works, harder if we go out of my hospital and of trouble for everyone, donors from strives to excel look at Uganda as a health system. across the world have received with what they Lack of medicines, structures, staff, messages of solidarity from Lacor. have. to the point where patients don’t get We have witnessed examples of an examination because too few are resilience, the art of adapting to And does not available. As a doctor, I am not in the hardship, and even examples of give up. -

Cags 25 Years Pages.Pmd

Canadian Association of General Surgeons The First 25 Years By Dr. Henry Thomas Gee Williams Canadian Association of General Surgeons Edited by Dr. G.W.N. Fitzgerald All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the Canadian Association of General Surgeons 774 promenade Echo Drive, Ottawa, ON K1S 5N8 Tel.: 613-730-6280 • Fax: 613-730-1116 [email protected] • www.cags-accg.ca Layout by Mary Fitzgerald, Dartmouth, NS Printed by ............. Canadian Association of General Surgeons CONTENTS The Beginning ........................................................................ 1 The Logo............................................................................... 13 Education Committee ........................................................... 17 Undergraduate Education Committee .................................. 19 Postgraduate Education Committee ..................................... 22 Continuing Medical Education............................................. 40 Manpower Practice and Economics Committee .................. 46 Program Committee ............................................................. 68 Research Committee ............................................................ 82 Recognition of Special Skills ............................................... 90 Trauma Committee ............................................................... 97 Head and Neck Surgery Committee ................................... 101 Colorectal Surgery Committee .......................................... -

Lavita Alcentro

la vita al centro fsc Testi a cura di Daniela Condorelli, giornalista, responsabile Comunicazione Fondazione Corti Fotografie di Mauro Fermariello, Seamus Murphy. Richard A. Rowe Grafica di copertina: Studio Anastasia ©Seamus Murphy Al dottor Matthew Lukwiya, brillante medico ugandese, amatissimo eroe del Lacor, e ai dodici dipendenti che, insieme a lui, hanno perso la vita per arginare l’epidemia di Ebola che ha devastato il Nord Uganda nel 2000. Di fronte alla morte di alcuni tra coloro che avevano accettato il suo invito a restare per presidiare l’ospedale e curare i malati di Ebola, Matthew disse: “...nel nostro personale mai una parola di risentimento, di rabbia, di pentimento... sono tutti giovani con davanti sogni e progetti per l’avvenire, eppure si prodigano, rischiando la vita e sacrificandola... Sono un dono che il presente e il futuro dovrà valorizzare “. Matthew Lukwiya, novembre 2000 Più che un ospedale, un fratello “Il mio nome è Dominique Atim Corti: sono nata in Nord Uganda, al Lacor Hospital di Gulu, oggi tra i più grandi e attrezzati poli ospedalieri non profit dell’Africa Equatoriale. Il Lacor, per me, è molto di più di un ospedale: è un fratello. Era un piccolo ospedale di trenta letti nel mezzo della savana quando, sessant’anni fa, i miei genitori, entrambi medici, l’hanno preso sotto le loro ali. Da allora è cresciuto diventando una cittadella della salute che ogni anno accoglie 250 mila pazienti e vede nascere quasi diecimila bambini. È perché il Lacor continui a dare il meglio ai più vulnerabili che, da 25 anni, esiste la Fondazione Corti, nata per affiancarlo e sostenerlo con risorse e competenze. -

1999-2000 Annual Report Telefilm Canada’S Offices

1999-2000 ANNUAL REPORT TELEFILM CANADA’S OFFICES OFFICES IN CANADA EUROPEAN OFFICE MONTRÉAL* PARIS 360 St. Jacques Street 5, rue de Constantine Suite 700 75007 Paris Montréal, Quebec France h2y 4a9 Phone: (33.1) 44.18.35.30 Phone: (514) 283-6363 Fax: (33.1) 47.05.72.76 Fax: (514) 283-8212 www.telefilm.gc.ca TORONTO 2 Bloor Street West 22nd Floor Toronto, Ontario m4w 3e2 Phone: (416) 973-6436 Fax: (416) 973-8606 VANCOUVER 310 – 440 Cambie Street Vancouver, British Columbia v6b 2n5 Phone: (604) 666-1566 Fax: (604) 666-7754 HALIFAX 1684 Barrington Street 3rd Floor Halifax, Nova Scotia b3j 2a2 Phone: (902) 426-8425 Fax: (902) 426-4445 OTTAWA 360 Albert Street Suite 1560 Ottawa, Ontario k1a 0m9 Phone: (613) 947-2938 Fax: (613) 947-2537 * Head office and Quebec Operations office ››› This annual report is published by the Communications and Public Affairs Department of Telefilm Canada with the participation of the Policies, Planning and Research Department. Additional copies may be obtained by writing Legal Deposit: to the following address: Bibliothèque nationale du Québec Telefilm Canada National Library of Canada Communications and Public Affairs 360 St. Jacques Street Graphic design: Suite 700 Agence Code communications Montréal, Quebec h2y 4a9 Pre-press: Grafix Studio Printing: Bowne de Montréal 2 Telefilm Canada ››› Annual Report 1999-2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Board Members and Senior Management ........................................................... 4 Letter to the Minister ................................................................................ -

L'eco Di Bergamo: Dall'uganda Al Papa Giovanni Per La Lotta Contro L

L’ECO DI BERGAMO 20 MERCOLEDÌ 24 LUGLIO 2013 La storia Bergamo chiama Africa a Dall’Uganda al Papa Giovanni per la lotta contro l’Aids L’epidemiologo Emmanuel Ochala del St. Mary’s Lacor Hospital di Gulu ospite di Nepios «Ora in Africa è possibile bloccare l’Hiv» DI SUSANNA PESENTI Africa non deve cialistico offre servizi di coun- «L’perdere altre ge- A selling, test volontario, cura del- nerazioni a causa ETÀ 33 anni le infezioni opportunistiche, te- dell’Aids, ma questo sarà possi- rapia antiretrovirale con follow bile solo se i farmaci antiretro- A up clinico e di laboratorio, pre- virali saranno resi disponibili CURRICULUM venzione della trasmissione ma- per tutti i malati». Emmanuel Ochola, terno-fetale. I pazienti vengono Emmanuel Ochola, epidemiolo- epidemiologo e responsabile seguiti anche a livello domicilia- go al St. Mary’s Hospital Lacor del Dipartimento di cura e re dai volontari dell’organizza- di Gulu e responsabile del Di- ricerca sull’Hiv del St. Mary zione "Comboni Samaritans". partimento di trattamento e ri- Lacor Hospital di Gulu, si è Sono una rete di valore inesti- cerca sull’Hiv del famoso ospe- laureato in medicina e mabile perché fanno informa- dale ugandese fondato dei me- chirurgia (2005) e zione e tengono d’occhio la si- dici italiani Lucille e Piero Cor- specializzato (2008) alla tuazione nei villaggi. In Uganda ti, è a Bergamo per visitare l’o- Makerere University di la gente va soprattutto a piedi e spedale Giovanni XXIII. «Tene- Kampala, Uganda. l’ospedale ha un bacino d’uten- vo a vedere come è organizzato» A za di centinaia di chilometri.