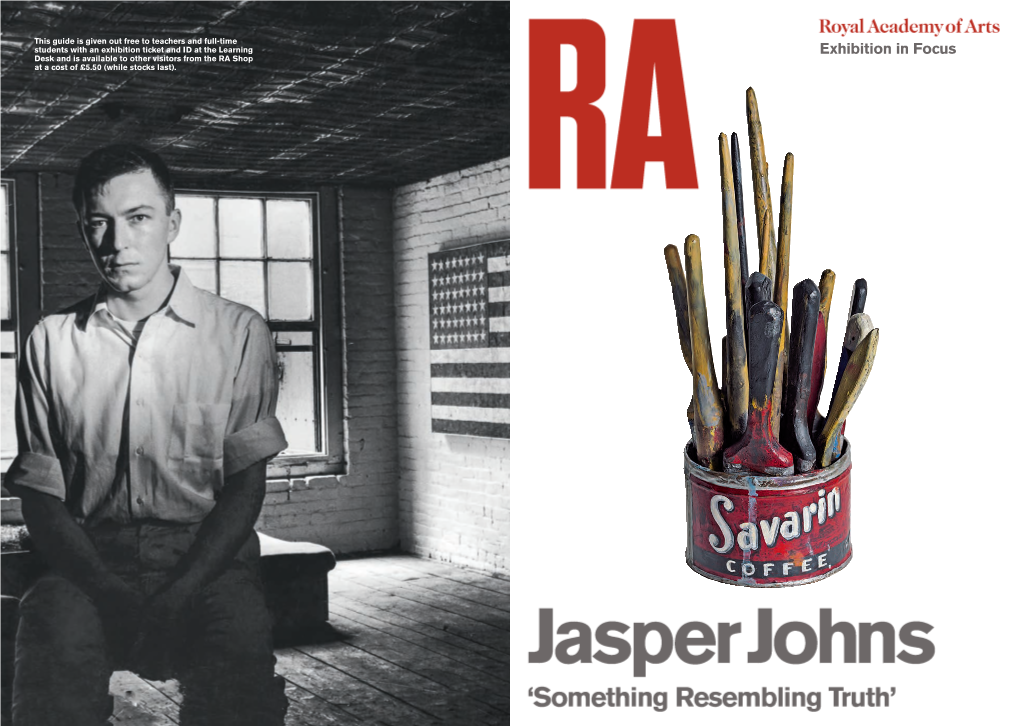

'Exhibition in Focus' Guide for Jasper Johns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

Art Masterpiece: Three Flags, 1958 by Jasper Johns

Art Masterpiece: Three Flags, 1958 by Jasper Johns Keywords: Symmetry, Repetition Symmetry: parts are arranged the same on both sides Repetition: a design that has parts that are used over and over again in a pleasing way. Grade: 1st Grade Activity: Painted Flags Meet the Artist (5 minutes): · He was born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, but grew up in South Carolina. He had little formal art education since there weren’t any art schools nearby. · When he moved to New York, he became friends with the prominent artists of the day. · In 1954, he had a dream that he painted a large American Flag. · He liked his art to be symmetrical, repetitious and minimalist. In other words, he wanted it to stand on its own and without the attachments of emotion. He liked the simple design of objects like the American Flag. · His Flag series made him famous as an artist. Possible Questions (10 minutes): • Do you see repetition in this picture? • Is it symmetrical? Are the parts arranged in the same basic way on both sides? • Describe the lines that you see... • What makes this picture different from a real American Flag? Property of Knox Art Masterpiece Revised 8/3/13 • What does our American Flag mean to you? Symbolism, liberty, freedom, pride. The American flag flies on the moon, sits atop Mount Everest, is hurtling out in space. The flag is how America signs her name. • Sometimes the Flag is hung at half-staff. Why? (To honor certain people who have died) • Who created the American Flag? Betsy Ross. -

Vt~ • He Moved to New York City When He Was 19 and Briefly Studied at a Well Uf Known Art School

Three Flags by Jasper Johns done in 19~, the artist painted 3 separate flags using what is known as encaustic which is the use of wax and pigment on canvas. He attached each of them to each other to create a 3 dimensional object. This form of art is known as pop art- using familiar imagery from everyday life. It was acquired by the Whitney Museum in New York City in 1980 for 1 million dollars. Meet the Artist: Jasper Johns • He was born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, but grew up in South Carolina. He began drawing when he was 3 but had little exposure to art education. ~ vv~ Vt~ • He moved to New York City when he was 19 and briefly studied at a well Uf known art school. He became friends with other prominent artists of the day and together they began developing their ideas on art concepts. • He is best known for his "Flag," (1954-55) painting after he had a dream about a large American Flag. • Many images in his art are recognizable symbols and familiar objects that stand on their own design that don't need interpretation or have a hidden meaning or emotion. • He liked the simple design of objects like the American Flag, the alphabet, numbers or a map of the United States as these symbols are powerful on their own. • He carefully chose the subject matter for his art based on its simplicity, symmetry, and basic patterns. • His Flag series was what made him famous as an artist but he also worked with other mediums. -

Art Masterpiece: Three Flags, 1958 by Jasper Johns

Three Flags, 1958 Jasper Johns Keywords: Pop Art, Monotype, Print, Texture Activity: Monoprint on foil Keywords Defined: • Pop Art - Style of art made popular in late 1950's early 1960's. Much of it represented images of common commercial images and objects. • Monotype - A one-of-a-kind print made by painting on a smooth metal, glass, stone plate or other smooth surface and then printing on paper. The paper, often dampened, is placed over the image and either burnished by hand or run through an etching press. The pressure of printing creates a texture not possible when painting directly on paper. The process produces a single unique print, thus an edition of one, by using pressure to transfer the image onto paper. The Monotype is a mirror image of what was drawn onto the original surface. • Print - a kind of artwork in which ink or paint is put onto a block (wood, linoleum, etc.) which has a design carved into it. The block is then pressed onto paper to make a print (copy) of the design. • Texture – an element of art. The way an object looks as though it feels, such as rough or smooth. Meet the Artist: • He was born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, but grew up in South Carolina. He had little official art education since there were no art schools nearby. • When he moved to New York, he became friends with the prominent artists of the day. • In 1954, he had a dream that he painted a large American Flag. • He liked his art to be symmetrical, repetitious and minimalist. -

Flag(1954–55) in Late 1954 Jasper Johns Destroyed Virtually All of His

Flag (1954–55) In late 1954 Jasper Johns destroyed virtually all of his previous work. He was twenty-four years old and had been living in New York since his discharge from the United States Army in May 1953. It was time, he remembers, “to stop becoming and to be an artist. I had a wish to determine what I was. what I wanted to do was find out what I did that other people didn’t, what I was that other people weren’t.” The impetus for the picture that launched his career came from a source that was uniquely his: “One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag, and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” Flag was one of several paintings that delivered a still- memorable jolt to the art world during Johns’s first solo exhibition, in New York in early 1958 at Leo Castelli’s new gallery. Of all the puzzling pictures, Flag’s cool, painterly appropriation of the Stars and Stripes attracted particular scrutiny. It was, wrote Robert Rosenblum, “easily described as an accurate painted replica of the American flag, but . as hard to explain in its unsettling power as the reasonable illogicalities of a Duchamp readymade. 4 Is it blasphemous or respectful, simple-minded or recondite?” 5 Flag 1954–55 (dated on reverse 1954) Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted 1 on plywood, three panels, overall 42 ⁄4 x 5 60 ⁄8" (107.3 x 153.8 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

MODERN ART and IDEAS 8 1962–1974 a Guide for Educators

MODERN ART AND IDEAS 8 1962–1974 A Guide for Educators Department of Education at The Museum of Modern Art MINIMALISM AND CONCEPTUALISM Artists included in this guide: John Baldessari, Joseph Beuys, Daniel Buren, Dan Flavin, Eva Hesse, Donald Judd, Yves Klein, Joseph Kosuth, Yayoi Kusama, Sol LeWitt, Gordon Matta-Clark, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. A NOTE TO EDUCATORS 2. USING THE EDUCATOR GUIDE 3. SETTING THE SCENE 7. LESSONS Lesson One: Serial Forms/Material Difference Lesson Two: Language Arts Lesson Three: Constructing Space Lesson Four: Public Interventions Lesson Five: Performance into Art 34. FOR FURTHER CONSIDERATION 36. GLOSSARY 39. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES 44. MoMA SCHOOL PROGRAMS No part of these materials may be reproduced or published in any form without prior written consent of The Museum of Modern Art. Design © 2007 The Museum of Modern Art, New York A NOTE TO EDUCATORS This is the eighth volume in the Modern Art and Ideas series for educators, which explores 1 the history of modern art through The Museum of Modern Art’s rich collection. While tra- A ditional art-historical categories are the organizing principle of the series, these parameters N O are used primarily as a means of exploring artistic developments and movements in con- T E junction with their social and historical contexts, with attention to the contributions of spe- T O cific artists. E D U C A This guide is informed by issues that arise from the selected works in a variety of mediums T O (painting, sculpture, collage, printmaking, photography, and, significantly, works that tran- R S scend the traditional division of mediums), but its organization and lesson topics are cre- ated with the school curriculum in mind, with particular application to social studies, visual art, history, and language arts. -

Jasper Johns and the Influence of Ludwig

JASPER JOHNS AND THE INFLUENCE OF LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN by PETER HIGGINSON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1972 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Fine Arts We accept this.thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July, 1974 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Depa rtment The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada ABSTRACT The influences upon Johns' work stem from varied fields of interests, ranging from Leonardo to John Cage, Hart Crane to Duchamp, Marshall McLuhan to Wittgenstein. The role that Wittgenstein's philosophy, plays has never been fully appreciated. What discussion has occurred - namely Max Kozloff's and Rosalind Krauss' - shows an inadequacy either through a lack of understanding or a super• ficiality towards the philosophical views. An in-depth analysis on this,, subject is invaluable in fully comprehending the ramifications of Johns' painting of the 60's. The intention of this paper is to examine Wittgenstein's influence and assess how his method of seeking out meaning in language is used by Johns in his paintings to explore meaning in art. -

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns's Paintings in The

The Role and the Nature of Repetition in Jasper Johns’s Paintings in the Context of Postwar American Art by Ela Krieger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Approved Dissertation Committee Prof. Dr. Isabel Wünsche Jacobs University Bremen Prof. Dr. Paul Crowther Alma Mater Europaea Ljubljana Dr. Julia Timpe Jacobs University Bremen Date of Defense: 5 June 2019 Social Sciences and Humanities Abstract Abstract From the beginning of his artistic career, American artist Jasper Johns (b. 1930) has used various repetitive means in his paintings. Their significance in his work has not been sufficiently discussed; hence this thesis is an exploration of the role and the nature of repetition in Johns’s paintings, which is essential to better understand his artistic production. Following a thorough review of his paintings, it is possible to broadly classify his use of repetition into three types: repeating images and gestures, using the logic of printing, and quoting and returning to past artists. I examine each of these in relation to three major art theory elements: abstraction, autonomy, and originality. When Johns repeats images and gestures, he also reconsiders abstraction in painting; using the logic of printing enables him to follow the logic of another medium and to challenge the autonomy of painting; by quoting other artists, Johns is reexamining originality in painting. These types of repetition are distinct in their features but complementary in their mission to expand the boundaries of painting. The proposed classification system enables a better understanding of the role and the nature of repetition in the specific case of Johns’s paintings, and it enriches our understanding of the use of repetition and its perception in art in general. -

The Leo Castelli Gallery in Metro Magazine: American Approaches to Post-Abstract Figuration in an Italian Context

Copyright by Dorothy Jean McKetta 2012 The Thesis Committee for Dorothy Jean McKetta Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Leo Castelli Gallery in Metro Magazine: American Approaches to Post-Abstract Figuration in an Italian Context APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Richard Shiff John R. Clarke The Leo Castelli Gallery in Metro Magazine: American Approaches to Post-Abstract Figuration in an Italian Context by Dorothy Jean McKetta, B.A.; B.F.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2012 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Paolo Barucchieri (1935-2012). Thank you, Paolo, for sharing your Italy with me. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the many people who have made this thesis possible. Thank you to the members of my thesis committee who attended my colloquium: Dr. Andrea Giunta, Dr. Linda Henderson, and Dr. Nassos Papalexandrou. All of your comments have helped to bring my topic into focus over the past few months. To my reader, Dr. John R. Clarke, thank you for encouraging me to write on Italy in the twentieth century, and for sharing your personal library so generously. And, of course, many thanks to Dr. Richard Shiff, my advisor, who suggested and that Metro magazine might help me find clues to Cy Twombly’s Roman milieu. Thank you for all your attention and trust. I would also like to acknowledge a few others who have helped along the way: Laura Schwartz, William Crain, Bob Penman, Maureen Howell, Jessamine Batario, my parents Randy and Terry McKetta. -

The Existence Or Non-Existence of a Contemporary Avant-Garde

THE EXISTENCE OR NON-EXISTENCE OF A CONTEMPORARY AVANT-GARDE A comparative research on historical avant-garde, neo avant-garde and contemporary art practices. Student: Claire Hoogakker Student number: 10246703 Supervisor: Dr. Gregor Langfeld Second reader: Dr. Miriam van Rijsingen Date: 13 July 2016 Amount of words: 21.313 MA Thesis Art History: Modern and Contemporary Art University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Art always was, and is, a force of protest of the humane against the pressure of domineering institutions … no less than it reflects their substance. - Theodor W. Adorno, Theses Upon Art and Religion Today, 1945. ! 1! Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 - 6 Theoretical Framework 6 - 7 Chapter 1: The Praxis of Life 8 - 23 The Historical Avant-Garde and The Praxis of Life 10 - 13 The Neo Avant-Garde and The Praxis of Life 13 - 17 Contemporary Artists and The Praxis of Life 18 - 23 Chapter 2: Medium Specificity 24 - 35 The Historical Avant-Garde and Medium Specificity 26 - 29 The Neo Avant-Garde and Medium Specificity 29 - 32 Contemporary Artists and Medium Specificity 32 - 35 Chapter 3: Institutional Critique 36 - 51 The Historical Avant-Garde and Institutional Critique 38 - 41 Neo Avant-Garde and Institutional Critique 41 - 46 Contemporary Artists and Institutional Critique 46 - 51 Conclusion 52 - 55 Bibliography 56 - 61 Lists of Images 62 - 106 Chapter 1: List of Images 62 - 77 Chapter 2: List of Images 78 - 93 Chapter 3: List of Images 94 - 106 ! 2! Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to sincerely thank my supervisor Dr. Gregor Langfeld for his time, his generous feedback and advice but most of all, for his trust in me and in this thesis. -

Oral History Interview with Leo Castelli, 1997 May 22

Oral history interview with Leo Castelli, 1997 May 22 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Leo Castelli, joined by his daughter, Nina Sundell, on May 22 and September 2, 1997. The interview took place in New York, N.Y., and was conducted by Andrew Decker for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. In 2016, staff at the Archives of American Art reviewed this transcript to make corrections. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANDREW DECKER: So, today's date is May 22, 1997. I am Andrew Decker and I am in the gallery of Leo Castelli, who has graciously agreed to be interviewed for the Archives of American Art. Some years ago you provided a great deal of information to the Archives about your work in the fifties and sixties, and I'm hoping to talk to you also about the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. LEO CASTELLI: Yes. MR. DECKER: The last interviews ended with your great interest in Minimal art— MR. CASTELLI: Mm-hmm. [Affirmative.] MR. DECKER: And Conceptual art, which you continued with for a number of years. MR. CASTELLI: Yes. MR. DECKER: Were there developments in that area that you found enjoyable or surprising? MR. -

Dedicated to General Idea 1969-1994 Esther Schipper Is Pleased To

Dedicated to General Idea 1969-1994 Esther Schipper is pleased to present AA Bronson’s White Flag, the artist’s second solo exhibition with the gallery. On September 11, 2001, AA Bronson was caught in Toronto when his flight home to New York was canceled. He watched in real time on television, as two airplanes punctured the twin towers of the World Trade Center, and then as the towers collapsed. It was seven days before he could rejoin his husband in lower Manhattan. What he found there is inscribed indelibly on his brain: a thick chalky dust of glass, concrete, paper, asbestos and human flesh that covered everything; and American flags, everywhere. White Flag presents seven paintings, each constructed of an American flag, purchased on eBay, mounted on raw linen, and coated in layers of an antique preparation of rabbit skin glue, chalk, and honey. This compound was, historically, used to prepare the ground upon which a painting was painted; it is literally the foundation of a history of painting. But here the ground becomes the painting itself, shrouding each flag—each with its history implicit in torn edges, holes and rips—in an elegiac ashen presence. The title White Flag is not merely descriptive of the paintings: it alludes to the plant White Flag, or Cemetery Iris, a white flower popular in Muslim and Christian cemeteries, cultivated for more than 3500 years. The plant is highly poisonous, invasive, and infertile. Indigenous to North Africa and the Middle East, it traveled with the Muslims to Spain and then with the Spanish to America.