The Existence Or Non-Existence of a Contemporary Avant-Garde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Preserving New Media Art: Re-Presenting Experience

Preserving New Media Art: Re-presenting Experience Jean Bridge Sarah Pruyn Visual Arts & Interactive Arts and Science, Theatre Studies, University of Guelph, Brock University Guelph, Canada St. Catharines, Canada [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords There has been considerable effort over the past 10 years to define methods for preservation, documentation and archive of new Art, performance art, relational art, interactive art, new media, art media artworks that are characterized variously as ephemeral, preservation, archive, art documentation, videogame, simulation, performative, immersive, participatory, relational, unstable or representation, experience, interaction, aliveness, virtual, technically obsolete. Much new media cultural heritage, authorship, instrumentality consisting of diverse and hybrid art forms such as installation, performance, intervention, activities and events, are accessible to 1. INTRODUCTION us as information, visual records and other relatively static This investigation has evolved from our interest in finding documents designed to meet the needs of collecting institutions documentation of artwork by artists who produce technologically and archives rather than those of artists, students and researchers mediated installations, performances, interventions, activities and who want a more affectively vital way of experiencing the artist’s events - the nature of which may be variously limited in time or creative intentions. It is therefore imperative to evolve existing duration, performance based, -

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

Teachers' Notes – 'Michael Landy: Saints Alive'

Michael Landy as St Jerome, 2012. © Michael Landy, courtesy of the Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Photo: The National Gallery, London. London. Photo: The National Gallery, courtesy of the Thomas Dane Gallery, 2012. © Michael Landy, Michael Landy as St Jerome, MICHAEL LANDY SAINTS ALIVE An introduction for teachers and students SAINTS ALIVE This exhibition consists of seven kinetic sculptures that are operated by visitors. The sculptures represent figures and stories of popular saints taken from the history of art. They are made from cast representations of details taken from National Gallery paintings, which have been combined with assemblages of recycled machinery, broken children’s toys and other unwanted junk. In the foyer to the exhibition, a selection of related drawings and collages is displayed. The collages are made from fragments cut out from reproductions of paintings in the collection. THE ROOTSTEIN HOPKINS ASSOCIATE ARTIST SCHEME The National Gallery is a historical collection that ends with work by Cézanne and the Post-Impressionists. At the time of the Gallery’s foundation in 1824, one of the stated aims was that it should provide a resource from which contemporary artists could learn and gain inspiration. Taking its cue from this idea, the Associate Artist Scheme began in 1989 with the appointment of Paula Rego. The essential requirement for the Associate Artist is that he or she makes new work by engaging with, and responding to the collection or some aspect of the collection. The artist is given a studio in the Gallery for a period of around two years. Michael Landy is the ninth artist to be invited to undertake this project. -

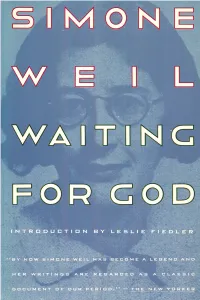

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Steve Mcqueen in Conversation with Artangel | April 2020

Press Release 29 April 2020 STEVE MCQUEEN IN CONVERSATION WITH ARTANGEL Monday 4 May, 7pm BST / 8pm CEST / 2pm EST ArtanGel.orG.uk Oscar-winning filmmaker and Turner Prize winning artist Steve McQueen will be joined by Artangel Co-Director James Lingwood on Monday 4 May for a live online conversation to discuss the artist’s work with Artangel spanning two decades. Steve McQueen first collaborated with Artangel on Caribs’ Leap / Western Deep, an immersive cinematic installation which premiered at Documenta X and in an underground space in London in 2002. In 2016, McQueen installed a new sculpture, Weight, in a cell in Reading Prison as part of Artangel’s acclaimed project, Inside. Most recently McQueen collaborated with Artangel, Tate and A New Direction for the epic project Year 3, resulting in one of the most ambitious visual portraits of citizenship ever undertaken in one of the world’s largest and most diverse cities. Viewers can join the event live from 7pm BST on Monday 4 May via the Artangel website and are encouraged to post questions following the conversation using the hashtag #ArtangelIsOpen on Twitter or Facebook. A link to join the event will be available on the Artangel website from 18.45 on 4 May. The conversation is part of a new programme of digital content initiated by Artangel to open up and encourage creativity during lockdown. The programme will revisit Artangel’s archive, exploring projects that are particularly pertinent today. Artangel’s work with Steve McQueen has allowed an exploration into themes of solitude and grief, collective representation and identity, to develop new work by the artist. -

Damien Hirst Visual Candy and Natural History

G A G O S I A N 7 February 2018 DAMIEN HIRST VISUAL CANDY AND NATURAL HISTORY EXTENDED! Through Saturday, March 3, 2018 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong I had my stomach pumped as a child because I ate pills thinking they were sweets […] I can’t understand why some people believe completely in medicine and not in art, without questioning either. —Damien Hirst Gagosian is pleased to present “Visual Candy and Natural History,” a selection of paintings and sculptures by Damien Hirst from the early- to mid-1990s. The exhibition coincides with Hirst’s most ambitious and complex project to date, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” on view at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice until December 3. Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s as the protagonist of a generation of British artists, Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art, beauty, religion, science, life and death. Through series as diverse as the ‘Spot Paintings’, ‘Medicine Cabinets’, ‘Natural History’ and butterfly ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings,’ he has investigated and challenged contemporary belief systems, tracing the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. This exhibition juxtaposes the joyful, colorful abstractions of his ‘Visual Candy’ paintings with the clinical forms of his ‘Natural History’ sculptures. Page 1 of 3 The ‘Visual Candy’ paintings allude to movements including Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, while the ‘Natural History’ sculptures—glass tanks containing biological specimens preserved in formaldehyde—reflect the visceral realities of scientific investigation through minimalist design. -

Art Masterpiece: Three Flags, 1958 by Jasper Johns

Art Masterpiece: Three Flags, 1958 by Jasper Johns Keywords: Symmetry, Repetition Symmetry: parts are arranged the same on both sides Repetition: a design that has parts that are used over and over again in a pleasing way. Grade: 1st Grade Activity: Painted Flags Meet the Artist (5 minutes): · He was born in 1930 in Augusta, Georgia, but grew up in South Carolina. He had little formal art education since there weren’t any art schools nearby. · When he moved to New York, he became friends with the prominent artists of the day. · In 1954, he had a dream that he painted a large American Flag. · He liked his art to be symmetrical, repetitious and minimalist. In other words, he wanted it to stand on its own and without the attachments of emotion. He liked the simple design of objects like the American Flag. · His Flag series made him famous as an artist. Possible Questions (10 minutes): • Do you see repetition in this picture? • Is it symmetrical? Are the parts arranged in the same basic way on both sides? • Describe the lines that you see... • What makes this picture different from a real American Flag? Property of Knox Art Masterpiece Revised 8/3/13 • What does our American Flag mean to you? Symbolism, liberty, freedom, pride. The American flag flies on the moon, sits atop Mount Everest, is hurtling out in space. The flag is how America signs her name. • Sometimes the Flag is hung at half-staff. Why? (To honor certain people who have died) • Who created the American Flag? Betsy Ross. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

A Heuristic Event: Reconsidering The

‘A heuristic event’: reconsidering the problem of the Johnsian conversation Amy K. Hamlin Does it mean anything? -Leo Steinberg, ‘Jasper Johns: the First Seven Years of His Art’, 1962 It is one of the great idées reçues in the history of contemporary art that Jasper Johns is difficult to interview. Despite his otherwise affable rapport, he is alleged to stonewall his interlocutors by blocking their efforts to find meaning in his artworks and intentions. He has given many interviews in the course of his career.1 These dialogues contain plenty of parry and joust that, at first glance, appear to yield very little insight. In what Michael Crichton dubbed the ‘Johnsian conversation’,2 the reader routinely encounters the sort of exchange that the late Leo Steinberg fictionalized in his now canonical essay on Johns in 1962.3 The interview, as Steinberg later acknowledged, was not transcribed from an actual dialogue, but This is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Interviewing Johns” that I presented on February 22, 2008 at the Annual Conference of the College Art Association in Dallas. Richard Shiff chaired the Art History Open Session entitled “New Criticism and an Old Problem.” I would like to thank Richard Shiff and Jonathan Katz for their insights following that presentation. I would also like to thank Charles Haxthausen and Wayne Roosa for their incisive comments and suggestions. 1 On the occasion of the exhibition Jasper Johns: A Retrospective held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1996, Kirk Varnedoe edited an anthology of Johns’ writings, sketchbook notes, and interviews that complemented the exhibition catalogue.