Between Nature and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calibration of Hydrological Models by PEST

Calibration of hydrological models by PEST Andrej Vidmar, Mitja Brilly University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Civil and Geodetic Engineering, Department of Environmental Civil Engineering, Ljubljana, Slovenia Kyiv, Ukraine, November 6-8, 2019 The drainage basin hydrological cycle (4D space) Water does not come into or leave planet earth. Water is continuously transferred between the atmosphere and the oceans. This is known as the global hydrological cycle. Complex proceses: • governed by nature • essentially stochastic • unique • non-recurring • changeable across space and time • non-linear Source: http://www.alevelgeography.com/drainage-basin-hydrological-system (Mikhail Lomonosov law of mass conservation in 1756) 2 XXVIII Danube Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, November 6-8, 2019 1st _ Why use a P-R modeling? • for education • for decision support • for data quality control • for water balance studies • for drought runoff forecasting (irrigation) • for fire risk warning • for runoff forecasting/prediction (flood warning and reservoir operation) • inflow forecast the most important input data in hydropower • for what happens if’ questions in watershed level 3 XXVIII Danube Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, November 6-8, 2019 2nd _ P-R modeling is used? • to compute design floods for flood risk detection • to extend runoff data series (or filling gaps) • to compute design floods for dam safety • to investigate the effects of land-use changes within the catchment • to simulate discharge from ungauged catchments • to simulate climate change effects • to compute energy production 4 XXVIII Danube Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, November 6-8, 2019 The basic principle 5 XXVIII Danube Conference, Kyiv, Ukraine, November 6-8, 2019 Modeling noise Structural noise . Conceptual noise (semi-distributed,…) . -

Acrocephalus, 2015, Letnik 36, Številka 164-165 (Pdf)

2015 letnik 36 številka 164/165 strani 1–104 volume 36 number 164/165 pages 1–104 Oblikovanje / Design: Jasna Andrič Prelom / Typesetting: NEBIA d. o. o. Tisk / Print: Schwarz print d. o. o. Naklada / Circulation: 1500 izvodov / copies Ilustracija na naslovnici / Front page: belohrbti detel / White-backed Woodpecker Dendrocopos leucotos risba / drawing: Jurij Mikuletič Ilustracija v uvodniku / Editorial page: mali martinec / Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos risba / drawing: Jurij Mikuletič Acrocephalus 36 (164/165): 1–4, 2015 LIFE – med življenjem in smrtjo LIFE – Between Life and Death Biodiverzitetna kriza je največja kriza, s katero se trenutno spopada človeštvo. Čeprav je izumiranje vrst naraven proces, je danes jasno, da je človek zaradi netrajnostne rabe naravnih virov to dinamiko popolnoma spremenil. Tako denimo ptice danes izumirajo 25-krat hitreje, kot bi bilo to evolucijsko pričakovano. Že desetletja se človeštvo zaveda, da je biodiverziteta le kazalec stanja naravnih sistemov, brez katerih družba ne bi obstala. Gre za t. i. ekosistemske storitve, koristi, ki jih narava ponuja človeku, a ne zaračunava zanje. Razdelimo jih lahko v štiri kategorije: (1) preskrba – naravni viri, pitna voda, les itd., (2) regulacija – varstvo pred erozijo, poplavami, naravnimi katastrofami, (3) podpora – fotosinteza, proizvodnja kisika, vezava CO2, opraševanje rastlin in (4) kultura – vse možnosti sprostitve, navdiha in regeneracije, ki jih človek išče in najde v naravi. Prekomerno izkoriščanje naravnih ekosistemov prinaša ljudem višji standard, a zmanjšuje dolgoročno preživetje človeške populacije. Številne raziskovalne skupine po vsem svetu se v zadnjem času ukvarjajo s finančnim vrednotenjem teh storitev. Tak pristop utemeljujejo z dejstvom, da vsi ti podporni sistemi prispevajo neposredno in posredno k dobrobiti človeštva in so sestavni del ekonomske vrednosti našega planeta. -

Politics, Feasts, Festivals SZEGEDI VALLÁSI NÉPRAJZI KÖNYVTÁR BIBLIOTHECA RELIGIONIS POPULARIS SZEGEDIENSIS 36

POLITICS, FEASTS, FESTIVALS SZEGEDI VALLÁSI NÉPRAJZI KÖNYVTÁR BIBLIOTHECA RELIGIONIS POPULARIS SZEGEDIENSIS 36. SZERKESZTI/REDIGIT: BARNA, GÁBOR MTA-SZTE RESEARCH GROUP FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS CULTURE A VALLÁSI KULTÚRAKUTATÁS KÖNYVEI 4. YEARBOOK OF THE SIEF WORKING GROUP ON THE RITUAL YEAR 9. MTA-SZTEMTA-SZTE VALLÁSIRESEARCH GROUP KULTÚRAKUTATÓ FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS CSOPORT CULTURE POLITICS, FEASTS, FESTIVALS YEARBOOK OF THE SIEF WORKING GROUP ON THE RITUAL YEAR Edited by Gábor BARNA and István POVEDÁK Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology Szeged, 2014 Published with the support of the Hungarian National Research Fund (OTKA) Grant Nk 81502 in co-operation with the MTA-SZTE Research Group for the Study of Religious Culture. Cover: Painting by István Demeter All the language proofreading were made by Cozette Griffin-Kremer, Nancy Cassel McEntire and David Stanley ISBN 978-963-306-254-8 ISSN 1419-1288 (Szegedi Vallási Néprajzi Könyvtár) ISSN 2064-4825 (A Vallási Kultúrakutatás Könyvei ) ISSN 2228-1347 (Yearbook of the SIEF Working Group on the Ritual Year) © The Authors © The Editors All rights reserved Printed in Hungary Innovariant Nyomdaipari Kft., Algyő General manager: György Drágán www.innovariant.hu https://www.facebook.com/Innovariant CONTENTS Foreword .......................................................................................................................... 7 POLITICS AND THE REMEMBraNCE OF THE Past Emily Lyle Modifications to the Festival Calendar in 1600 and 1605 during the Reign of James VI and -

From Slovenian Farms Learn About Slovenian Cuisine with Dishes Made by Slovenian Housewives

TOURISM ON FARMS IN SLOVENIA MY WAY OF COUNTRYSIDE HOLIDAYS. #ifeelsLOVEnia #myway www.slovenia.info www.farmtourism.si Welcome to our home Imagine the embrace of green 2.095.861 surroundings, the smell of freshly cut PEOPLE LIVE grass, genuine Slovenian dialects, IN SLOVENIA (1 JANUARY 2020) traditional architecture and old farming customs and you’ll start to get some idea of the appeal of our countryside. Farm 900 TOURIST tourism, usually family-owned, open their FARMS doors and serve their guests the best 325 excursion farms, 129 wineries, produce from their gardens, fields, cellars, 31 “Eights” (Osmice), smokehouses, pantries and kitchens. 8 camping sites, and 391 tourist farms with Housewives upgrade their grandmothers’ accommodation. recipes with the elements of modern cuisine, while farm owners show off their wine cellars or accompany their guests to the sauna or a swimming pool, and their MORE THAN children show their peers from the city 200.000 how to spend a day without a tablet or a BEE FAMILIES smartphone. Slovenia is the home of the indigenous Carniolan honeybee. Farm tourism owners are sincerely looking Based on Slovenia’s initiative, forward to your visit. They will help you 20 May has become World Bee Day. slow down your everyday rhythm and make sure that you experience the authenticity of the Slovenian countryside. You are welcome in all seasons. MORE THAN 400 DISTINCTIVE LOCAL AND REGIONAL FOODSTUFFS, DISHES AND DRINKS Matija Vimpolšek Chairman of the Association MORE THAN of Tourist Farms of Slovenia 30.000 WINE PRODUCERS cultivate grapevines on almost 16,000 hectares of vineyards. -

Načrt Šolskih Poti V Šolskem Okolišu Oš Dragatuš

NAČRT ŠOLSKIH POTI V ŠOLSKEM OKOLIŠU OŠ DRAGATUŠ ŠOLSKO LETO 2019/2020 Koordinatorica za promet: Sabina Lukežič Ravnatelj: Stanislav Dražumerič - 1 - KAZALO: UVOD ....................................................................................................................................4 1 OTROCI POTREBUJEJO POMOČ IN NADZOR............................................................5 1.1 KAJ ZMOREJO OTROCI ..........................................................................................5 1.2 OTROCI V PROMETU POTREBUJEJO POMOČ ODRASLIH ................................5 1.3 PROMETNA VZGOJA VEDNO IN POVSOD ..........................................................5 1.3.1 VZOR ODRASLIH ............................................................................................5 1.3.2 UČENJE ............................................................................................................6 1.3.3 HOJA PO CESTI BREZ PLOČNIKOV .............................................................7 1.3.4 PREČKANJE CESTE ........................................................................................7 1.3.5 PROMETNI ZNAKI ..........................................................................................8 1.3.6 UTRJEVANJE VEDENJA .................................................................................9 1.4 PROMETNA VZGOJA OTROK V ŠOLI ...................................................................9 1.4.1 SESTAVINE POUKA PROMETNE VZGOJE ................................................ 10 1.4.2 PROGRAM -

PRILOGA 1 Seznam Vodnih Teles, Imena in Šifre, Opis Glede Na Uporabljena Merila Za Njihovo Določitev in Razvrstitev Naravnih Vodnih Teles V Tip

Stran 4162 / Št. 32 / 29. 4. 2011 Uradni list Republike Slovenije P R A V I L N I K o spremembah in dopolnitvah Pravilnika o določitvi in razvrstitvi vodnih teles površinskih voda 1. člen V Pravilniku o določitvi in razvrstitvi vodnih teles površin- skih voda (Uradni list RS, št. 63/05 in 26/06) se v 1. členu druga alinea spremeni tako, da se glasi: »– umetna vodna telesa, močno preoblikovana vodna telesa in kandidati za močno preoblikovana vodna telesa ter«. 2. člen V tretjem odstavku 6. člena se v drugi alinei za besedo »vplive« doda beseda »na«. 3. člen Priloga 1 se nadomesti z novo prilogo 1, ki je kot priloga 1 sestavni del tega pravilnika. Priloga 4 se nadomesti z novo prilogo 4, ki je kot priloga 2 sestavni del tega pravilnika. 4. člen Ta pravilnik začne veljati petnajsti dan po objavi v Ura- dnem listu Republike Slovenije. Št. 0071-316/2010 Ljubljana, dne 22. aprila 2011 EVA 2010-2511-0142 dr. Roko Žarnić l.r. Minister za okolje in prostor PRILOGA 1 »PRILOGA 1 Seznam vodnih teles, imena in šifre, opis glede na uporabljena merila za njihovo določitev in razvrstitev naravnih vodnih teles v tip Merila, uporabljena za določitev vodnega telesa Ime Zap. Povodje Površinska Razvrstitev Tip Pomembna Presihanje Pomembna Pomembno Šifra vodnega Vrsta št. ali porečje voda v tip hidro- antropogena različno telesa morfološka fizična stanje sprememba sprememba 1 SI1118VT Sava Radovna VT Radovna V 4SA x x x VT Sava Sava 2 SI111VT5 Sava izvir – V 4SA x x x Dolinka Hrušica MPVT Sava 3 SI111VT7 Sava zadrževalnik MPVT x Dolinka HE Moste Blejsko VTJ Blejsko 4 SI1128VT Sava J A2 x jezero jezero VTJ Bohinjsko 5 SI112VT3 Sava Bohinjsko J A1 x jezero jezero VT Sava Sava 6 SI11 2VT7 Sava Sveti Janez V 4SA x x Bohinjka – Jezernica VT Sava Jezernica Sava 7 SI1 1 2VT9 Sava – sotočje V 4SA x x Bohinjka s Savo Dolinko Uradni list Republike Slovenije Št. -

Številka: 900-68/2020 Datum: 5. 11. 2020 ČLANOM

OBČINA ČRNOMELJ OBČINSKI SVET 8340 Črnomelj, Trg svobode 3 tel. (07) 306-11-00 e-pošta: [email protected] Številka: 900-68/2020 Datum: 5. 11. 2020 ČLANOM OBČINSKEGA SVETA OBČINE ČRNOMELJ Zadeva: SKLIC 16. REDNE SEJE OBČINSKEGA SVETA OBČINE ČRNOMELJ Na podlagi 33. člena Zakona o lokalni samoupravi (Uradni list RS, št. 94/07 – uradno prečiščeno besedilo, 76/08, 79/09, 51/10, 40/12 – ZUJF, 14/15 – ZUUJFO, 11/18 – ZSPDSLS-1, 30/18 in 61/20 – ZIUZEOP-A), 18. člena Statuta občine Črnomelj (Ur.l. RS, št. 83/11, 24/14 in 66/16), 23. in 25. člena Poslovnika Občinskega sveta Občine Črnomelj (Ur.l. RS, št. 103/13, 4/18 in 65/19) S K L I C U J E M 16. redno sejo Občinskega sveta občine Črnomelj v ČETRTEK, 12. novembra 2020, ob 17. uri v dvorani Kulturnega doma Črnomelj, Ulica Otona Župančiča 1, Črnomelj DNEVNI RED: 1. Otvoritev seje in ugotovitev prisotnosti 2. Sprejem dnevnega reda 3. Poročilo župana o izvrševanju sklepov OS in aktivnostih občine 4. Razprava in sklepanje o zapisniku 15. redne seje Občinskega sveta občine Črnomelj 5. Predlog za izdajo Odloka o ustanovitvi javnega vzgojno-izobraževalnega zavoda Osnovna šola Mirana Jarca Črnomelj 6. Predlog za izdajo Odloka o ustanovitvi javnega vzgojno-izobraževalnega zavoda Osnovna šola Loka Črnomelj 7. Predlog za izdajo Odloka o ustanovitvi javnega vzgojno-izobraževalnega zavoda Osnovna šola komandanta Staneta Dragatuš 8. Predlog za izdajo Odloka o ustanovitvi javnega vzgojno-izobraževalnega zavoda Osnovna šola Vinica 9. Predlog za izdajo Odloka o ustanovitvi javnega vzgojno-izobraževalnega zavoda Vrtec Otona Župančiča Črnomelj 10. -

WHAT IMAGES of OXEN CAN TELL US Metaphorical Meanings and Everyday Working Practices

WHAT IMAGES OF OXEN CAN TELL US Metaphorical meanings and everyday working practices Inja Smerdel Introduction Although it seems that researchers from the humanities interested in working animals pay far more attention to the horse than the ox,1 there are individuals who have made some important observations about the significance of oxen in human history. For example, in her recent contribution on harnessing oxen using two basic forms of yoke,2 Cozette Griffin-Kremer (2007: 66) describes these draught animals which, from the time when they were first domesticated and worked until they disappeared from farms as a result of mechanisation, have used their harnessed energy and strength to pull tree trunks and rocks, as well as powering various tools, equipment and transport devices – from ards, ploughs, carts and sledges to threshing machines and mills – as "a wonderful machine that transformed the surface of the earth". In his book Horses, Oxen and Technological Innovation John Langdon (1986: 8) writes that, apart from mules and donkeys, "oxen carried all the burden for ploughing and hauling in ancient times". Rolf Minhorst (1990: 37), the author of a detailed historical study of draught animals in Germany,3 observes that "the draught ox had revolutionised the agriculture of the Neolithic period" and that "cattle husbandry in Europe has determined our cultural development from the very beginning". Quite a number of fundamental cultural values have also been identified in relation to attitudes to domesticated animals on other continents. Relevant anthropological studies have identified syntagms such as the African "cattle complex" (Campbell 2005: 97; cf. -

Gap Analysis Report Kamnik

GAP ANALYSIS REPORT KAMNIK GAP Analysis for Cultural-led Development of Small Version2 and Medium Sized Cities – Kamnik 05 2020 Page 1 Contents 1. Gap Analysis Reports ................................................................................. 5 1.1. Urban Identity / Town’s profile ................................................................. 5 1.1.1. City atmosphere ................................................................................. 5 1.1.2. Attitudes of citizens ............................................................................ 5 1.1.3. Citizens ............................................................................................ 5 1.1.4. Traditions ......................................................................................... 6 1.1.4.1. Historical traditions and habits ............................................................ 6 1.1.4.2. Contemporary traditions .................................................................... 6 1.1.5. Cultural heritage ................................................................................ 7 1.1.6. Products ........................................................................................... 7 1.1.7. Trades and crafts ................................................................................ 7 2. Cultural and Creative Industries and the creativity of the economic sector ........... 9 2.1.1. Activity level of the producers of cultural and creative products ................... 9 2.1.1.1. Music ........................................................................................... -

(PAF) for NATURA 2000 in SLOVENIA

PRIORITISED ACTION FRAMEWORK (PAF) FOR NATURA 2000 in SLOVENIA pursuant to Article 8 of Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (the Habitats Directive) for the Multiannual Financial Framework period 2021 – 2027 Contact address: Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning Dunajska 48 SI- 1000 Ljubljana Slovenia [email protected] PAF SI 2019 A. Introduction A.1 General introduction Prioritised action frameworks (PAFs) are strategic multiannual planning tools, aimed at providing a comprehensive overview of the measures that are needed to implement the EU-wide Natura 2000 network and its associated green infrastructure, specifying the financing needs for these measures and linking them to the corresponding EU funding programmes. In line with the objectives of the EU Habitats Directive1 on which the Natura 2000 network is based, the measures to be identified in the PAFs shall mainly be designed "to maintain and restore, at a favourable conservation status, natural habitats and species of EU importance, whilst taking account of economic, social and cultural requirements and regional and local characteristics". The legal basis for the PAF is Article 8 (1) of the Habitats Directive2, which requires Member States to send, as appropriate, to the Commission their estimates relating to the European Union co-financing which they consider necessary to meet their following obligations in relation to Natura 2000: to establish the necessary conservation measures involving, if need be, appropriate management plans specifically designed for the sites or integrated into other development plans, to establish appropriate statutory, administrative or contractual measures which correspond to the ecological requirements of the natural habitat types in Annex I and the species in Annex II present on the sites. -

Monitoring Kakovosti Površinskih Vodotokov V Sloveniji V Letu 2006

REPUBLIKA SLOVENIJA MINISTRSTVO ZA OKOLJE IN PROSTOR AGENCIJA REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE ZA OKOLJE MONITORING KAKOVOSTI POVRŠINSKIH VODOTOKOV V SLOVENIJI V LETU 2006 Ljubljana, junij 2008 REPUBLIKA SLOVENIJA MINISTRSTVO ZA OKOLJE IN PROSTOR AGENCIJA REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE ZA OKOLJE MONITORING KAKOVOSTI POVRŠINSKIH VODOTOKOV V SLOVENIJI V LETU 2006 Nosilka naloge: mag. Irena Cvitani č Poro čilo pripravili: mag. Irena Cvitani č in Edita Sodja Sodelavke: mag. Mojca Dobnikar Tehovnik, Špela Ambroži č, dr. Jasna Grbovi ć, Brigita Jesenovec, Andreja Kolenc, mag. Špela Kozak Legiša, mag. Polona Mihorko, Bernarda Rotar Karte pripravila: Petra Krsnik mag. Mojca Dobnikar Tehovnik dr. Silvo Žlebir VODJA SEKTORJA GENERALNI DIREKTOR Monitoring kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006 Podatki, objavljeni v Poro čilu o kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006, so rezultat kontroliranih meritev v mreži za spremljanje kakovosti voda. Poro čilo in podatki so zaš čiteni po dolo čilih avtorskega prava, tisk in uporaba podatkov sta dovoljena le v obliki izvle čkov z navedbo vira. ISSN 1855 – 0320 Deskriptorji: Slovenija, površinski vodotoki, kakovost, onesnaženje, vzor čenje, ocena stanja Descriptors: Slovenia, rivers, quality, pollution, sampling, quality status Monitoring kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006 KAZALO VSEBINE 1 POVZETEK REZULTATOV V LETU 2006 ........................................................................................ 1 2 UVOD ....................................................................................................................................... -

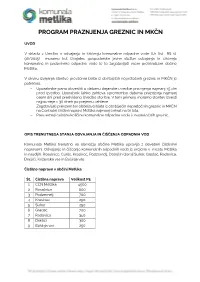

Program Praznjenja Greznic in Mkčn

PROGRAM PRAZNJENJA GREZNIC IN MKČN UVOD V skladu z Uredbo o odvajanju in čiščenju komunalne odpadne vode (Ur. list RS št. 98/2015) moramo kot izvajalec gospodarske javne službe odvajanja in čiščenja komunalne in padavinske odpadne vode le to zagotavljati vsem prebivalcem občine Metlika. V okviru izvajanja storitve prevzema blata iz obstoječih nepretočnih greznic in MKČN je potrebno: Uporabnike pisno obvestiti o datumu dejanske izvedbe praznjenja najmanj 15 dni pred izvedbo. Uporabnik lahko zahteva spremembo datuma praznjenja najmanj osem dni pred predvideno izvedbo storitve. V tem primeru moramo storitev izvesti najpozneje v 30 dneh po prejemu zahteve. Zagotavljati prevzem ter obdelavo blata iz obstoječih nepretočnih greznic in MKČN na Centralni čistilni napravi Metlika najmanj enkrat na tri leta. Prevzemati celotne količine komunalne odpadne vode iz nepretočnih greznic. OPIS TRENUTNEGA STANJA ODVAJANJA IN ČIŠČENJA ODPADNIH VOD Komunala Metlika trenutno na območju občine Metlika upravlja z devetimi čistilnimi napravami. Odvajanje in čiščenje komunalnih odpadnih voda je urejeno v mestu Metlika in naseljih: Rosalnice, Čurile, Krasinec, Podzemelj, Dolnji in Gornji Suhor, Gradac, Radovica, Drašiči, Križevska vas in Bušinja vas. Čistilne naprave v občini Metlika Št. Čistilna naprava Velikost PE 1 CČN Metlika 4500 2 Rosalnice 600 3 Podzemelj 700 4 Krasinec 250 5 Suhor 250 6 Gradac 700 7 Radovica 350 8 Drašiči 300 9 Bušinja vas 250 PROGRAM IZVAJANJA STORITEV, VEZANIH NA GREZNICE IN MKČN Število greznic in MKČN do 50 PE: V občini Metlika imamo 1178 greznic in 30 MKČN. Evidenca podatkov: Trenutno imamo vzpostavljeno delno evidenco podatkov o greznicah. Ob prvem praznjenju greznic bomo pridobili še ostale podatke, kateri se vnašajo na delovni nalog črpanja in odvoza grezničnih gošč (priloga 1).