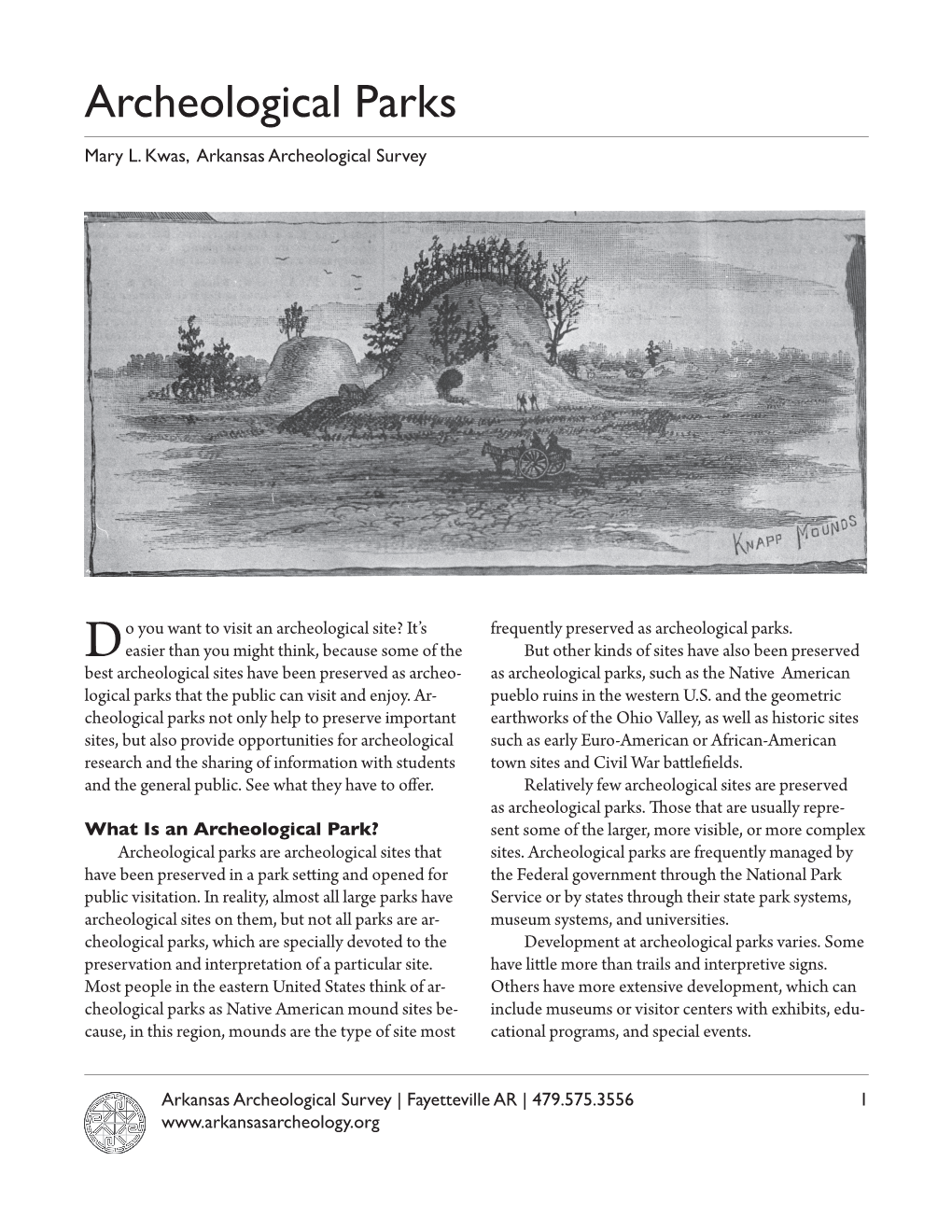

Archeological Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin

Lexicon of Pleistocene Stratigraphic Units of Wisconsin ON ATI RM FO K CREE MILLER 0 20 40 mi Douglas Member 0 50 km Lake ? Crab Member EDITORS C O Kent M. Syverson P P Florence Member E R Lee Clayton F Wildcat A Lake ? L L Member Nashville Member John W. Attig M S r ik be a F m n O r e R e TRADE RIVER M a M A T b David M. Mickelson e I O N FM k Pokegama m a e L r Creek Mbr M n e M b f a e f lv m m i Sy e l M Prairie b C e in Farm r r sk er e o emb lv P Member M i S ill S L rr L e A M Middle F Edgar ER M Inlet HOLY HILL V F Mbr RI Member FM Bakerville MARATHON Liberty Grove M Member FM F r Member e E b m E e PIERCE N M Two Rivers Member FM Keene U re PIERCE A o nm Hersey Member W le FM G Member E Branch River Member Kinnickinnic K H HOLY HILL Member r B Chilton e FM O Kirby Lake b IG Mbr Boundaries Member m L F e L M A Y Formation T s S F r M e H d l Member H a I o V r L i c Explanation o L n M Area of sediment deposited F e m during last part of Wisconsin O b er Glaciation, between about R 35,000 and 11,000 years M A Ozaukee before present. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Further Investigations Into the King George

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22) Harry Gene Brignac Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brignac Jr, Harry Gene, "Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22)" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE KING GEORGE ISLAND MOUNDS SITE (16LV22) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Harry Gene Brignac Jr. B.A. Louisiana State University, 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to give thanks to God for surrounding me with the people in my life who have guided and supported me in this and all of my endeavors. I have to express my greatest appreciation to Dr. Rebecca Saunders for her professional guidance during this entire process, and for her inspiration and constant motivation for me to become the best archaeologist I can be. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT Norman, Oklahoma 2017 ALTERNATE PATHWAYS TO RITUAL POWER: EVIDENCE FOR CENTRALIZED PRODUCTION AND LONG-DISTANCE EXCHANGE BETWEEN NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN CADDO COMMUNITIES A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Asa Randall ______________________________ Dr. Amanda Regnier ______________________________ Dr. Scott Hammerstedt ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Bonnie Pitblado ______________________________ Dr. Michael Winston © Copyright by SHAWN PATRICK LAMBERT 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication I dedicate my dissertation to my loving grandfather, Calvin McInnish and wonderful twin sister, Kimberly Dawn Thackston. I miss and love you. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to give my sincerest gratitude to Patrick Livingood, my committee chair, who has guided me through seven years of my masters and doctoral work. I could not wish for a better committee chair. I also want to thank Amanda Regnier and Scott Hammerstedt for the tremendous amount of work they put into making me the best possible archaeologist. I would also like to thank Asa Randall. His level of theoretical insight is on another dimensional plane and his Advanced Archaeological Theory class is one of the best I ever took at the University of Oklahoma. I express appreciation to Bonnie Pitblado, not only for being on my committee but emphasizing the importance of stewardship in archaeology. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

April 2013 Volume 40 Number 4

APRIL 2013 VOLUME 40 NUMBER 4 Conservation Leadership Corps nterested in being a leader in con- opportunity to network with state, fed- iservation? eral and private conservation organi- Interested in having your voice zations. heard on conservation issues by Wiscon- All your expenses for involvement in sin and National policymakers? the program will be paid for by the Wis- The Wisconsin Wildlife Federation consin Wildlife Federation. At the suc- is creating a Conservation Leadership cessful completion of the program you Training Program for you! will receive a $250 scholarship to further We welcome high school students in your conservation education! their junior/senior year or freshman/ Please visit our website: www.wiwf. sophomore college students to receive org for further details. You may also con- training in conservation leadership, con- tact Leah McSherry, WWF Conservation servation policy development and how to Leadership Corps Coordinator at lmc- advocate for sound conservation policies. [email protected] or George Meyer, WWF Training will be provided by experienced Executive Director at georgemeyer@tds. conservation leaders. net with any questions or to express your Training will provide an excellent interest in the program. General Information on the Conservation Leadership Corps he Board of Directors of and presented conservation reso- didates are encouraged to attend Tthe Wisconsin Wildlife lutions may be adopted by WWF most, if not all, of these events. Federation (WWF) has to serve as official policies. All expenses encountered while initiated an exciting new program Training will be provided by participating in the CLC program to assist in the development of fu- current and former natural re- will be covered by WWF. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Planpaclet5-27-08.Pdf

AQUORUMOFTHEADMINISTRATIONCOMMITTEE,BOARDOFPUBLICWORKS,PARKBOARD,AND/ORCOMMON COUNCILMAYATTENDTHISMEETING;(ALTHOUGHITISNOTEXPECTEDTHATANYOFFICIALACTIONOFANYOF THOSEBODIESWILLBETAKEN). CITYOFMENASHA PlanCommission CouncilChambers,3rdFloorCityHall-140MainStreet,Menasha May27,2008 3:30PM AGENDA Back Print 1. CALLTOORDER A. 2. ROLLCALL/EXCUSEDABSENCES A. 3. PUBLICCOMMENTSONANYMATTEROFCONCERNTOTHECITY Five(5)minutetimelimitforeachperson A. 4. DISCUSSION A. None 5. ACTIONITEMS A. PlanCommissionResolution-01-2008-RecommendingAdoptionoftheCityof MenashaYear2030ComprehensivePlan (previouslyreceivedinthe5/20/08Plan Attachments Commissionpacket) 6. ADJOURNMENT A. Menashaiscommittedtoitsdiversepopulation.OurNon-Englishspeakingpopulationorthosewithdisabilitiesareinvitedto contacttheCommunityDevelopmentDepartmentat967-3650atleast24-hoursinadvanceofthemeetingsospecial accommodationscanbemade. Plan Commission Resolution 01-2008 RECOMMENDATION OF THE PLAN COMMISSION TO ADOPT THE CITY OF MENASHA YEAR 2030 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN WHEREAS, pursuant to sections 62.23(2) and (3), Wisconsin Statutes, for cities, villages, and those towns exercising village powers under section 60.22(3), the City of Menasha is authorized to prepare and adopt a comprehensive plan consistent with the content and procedure requirements in sections 66.1001(1)(a), 66.1001(2), and 66.1001(4); and WHEREAS, the Plan Commission participated in the production of City of Menasha Year 2030 Comprehensive Plan in conjunction with a multi-jurisdictional planning effort to prepare -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2004 An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas William Glenn Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, William Glenn, "An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas" (2004). Master's Theses. 3873. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3873 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTENSIVE SURFACE COLLECTION AND INTRASITE SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM THE COY MOUND SITE (3LN20), CENTRAL ARKANSAS by William Glenn Hill A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts Department of Anthropology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2004 Copyright by William Glenn Hill 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, my pursuit in archaeology would be less meaningful without the accomplishments of Dr. Randall McGuire, Dr. H. Martin Wobst, and Dr. Michael Nassaney. They have provided a theoretical perspective in archaeology that has integrated and given greater meaning to my own social and archaeological interests. I would especially like to especially thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Michael Nassaney, for the stimulating opportunity to explore research within this theoretical perspective, and my other committee members, Dr.