Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sons of Anarchy - Bratva Pdf

FREE SONS OF ANARCHY - BRATVA PDF Christopher Golden,Kurt Sutter | 320 pages | 11 Nov 2014 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783296927 | English | London, United Kingdom Christopher Golden - Wikipedia Sons of Anarchy is an American action crime drama television series created by Kurt Sutter that aired from to It follows the lives of a close-knit outlaw motorcycle club operating in Charming, a fictional town in California 's Central Valley. The show stars Charlie Hunnam as Jackson "Jax" Tellerwho is initially the vice president and subsequently the president of the club. After discovering a manifesto written by Sons of Anarchy - Bratva late father, John, who previously led the MC, he soon begins to question the club, himself, and his relationships. Love, brotherhood, Sons of Anarchy - Bratva, betrayal, and redemption are consistent themes throughout the show. Sons of Anarchy premiered on September 3,on the cable network FX. The series's third season attracted an average of 4. The season 4 and 5 premieres were the two highest-rated Sons of Anarchy - Bratva in FX's history. The series finale premiered on December 9, This series explored vigilantismgovernment corruption, and racism, and depicted an outlaw motorcycle club as an analogy for human transformation. David Labravaa real-life member of the Oakland chapter of Hells Angelsserved as a technical adviser, and also played the recurring character Happy Lowmanthe club's assassin. In NovemberSutter indicated that he was in talks with FX to make a Sons of Anarchy prequel set in the s [7]. In Februaryhe said Sons of Anarchy - Bratva would not begin work on the prequel, which is likely to be titled "The First 9" [ citation needed ]. -

YOGIS of ANARCHY” an Introduction to Kundalini Yoga with Charlie Hunnam and Ryan Hurst Sunday, May 19Th from 8:30 AM to 9:30 AM Happiness Is Your Birthright

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MOTOR CITY COMIC CON ANNOUNCES YOGA CLASS, “YOGIS OF ANARCHY” An introduction to Kundalini Yoga with Charlie Hunnam and Ryan Hurst Sunday, May 19th from 8:30 AM to 9:30 AM Happiness is your birthright NOVI, MI. (March 13, 2019) – Motor City Comic Con, Michigan’s longest and largest comic pop- culture event, is pleased to announce “Sons of Anarchy” stars Charlie Hunnam and Ryan Hurst will teach an introduction to Kundalini Yoga class on Sunday, May 19th at 8:30 AM. Tickets for “Yogis of Anarchy” are on sale now on the Motor City Comic Con website and cost $75.00. Attendees are encouraged to bring their own yoga mat and to wear loose fitting clothes as well as a head cover or a hat. All attendees will have to provide proof of admission upon entering the yoga class. To purchase tickets, go to www.motorcitycomiccon.com/tickets. Kundalini Yoga, was brought to the West in 1969 by Yogi Bhajan, is an uplifting blend of spiritual and physical practices and incorporates movement, dynamic breathing techniques, meditation, and the chanting of mantras. The goal of this type of yoga is to build physical vitality and increase consciousness. The power of this yoga comes from the Kundalini (Sanskrit for “coiled serpent”), an enormous reserve of untapped potential within each of us, located around the sacrum or “sacred bone” at the base of the spine. By using proven techniques to gradually awaken this benign serpent and safely deploy its amazing beneficial powers, your life will be transformed into one of health, happiness and harmony. -

Decoding Deviance with the Sons of Anarchy

Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol. 18, No. 2, June 2018, pp. 90-104. doi:10.14434/josotl.v18i2.22515 Decoding Deviance with the Sons of Anarchy Joseph Kremer Washington State University [email protected] Kristin Cutler Washington State University Abstract: This article explicates the ways that the popular television series Sons of Anarchy in conjunction with our content analysis coding tool can be used to teach theories and concepts central to Sociology of Deviance courses. We detail how students learned to understand deviance as a social constructed phenomenon by coding and analyzing the behaviors of their most liked and most hated Sons characters. Evidence extrapolated from students’ final projects, class discussions, and course evaluations suggests that this pedagogical technique creates a systematic teaching method enabling students to more actively engage in the course while enhancing connections to the course materials. Keywords: deviance, social construction of deviance, popular culture, content analysis Using television and film as a pedagogical tool in sociology is far from a new phenomenon. Scholars have attested to the fact that using television and film helps bring to life abstract sociological theories and concepts, helps to better engage students with course materials, and as a result stimulate their sociological imaginations (Burton, 1988; Champoux, 1997; Demerath III, 1981; Donaghy, 2000; Eaton & Uskul, 2004; Hannon & Marullo, 1988; Hutton & Mak, 2014; Khanna & Harris, 2015; Livingston, 2004; Loewen, 1991; Melander & Wortmann, 2011; Nefes, 2014; Trier, 2010; Wosner & Boyns, 2013). For example, when speaking to the benefits of using the cinema as a teaching tool Champoux (1999) states: “viewers are not passive observers. -

1L-Mock-Trial-Case-File Spring-2021

NO. 20-04202-CV TARA KNOWLES TELLER, individually § IN THE 42nd DISTRICT COURT and as Administrator of the Estate of JAX § TELLER, and as Next Friend for ABEL § TELLER § Plaintiff, § IN AND FOR LUBBOCK COUNTY § v. § SONS OF ANARCHY TRUCKING § EMPIRE, INC., § Defendant. § STATE OF LONE STAR Prepared by: Jacy Pawelek & Patricia Cabrera Texas Tech University School of Law ‘21 3311 18th Street Lubbock, Texas 79409 Copyright 2021 All Rights Reserved This case file was commissioned by the Texas Tech Board of Barristers and was prepared by Jacy Pawelek and Patricia Cabrera for the Spring 2021 1L Mock Trial Competition STATEMENT OF THE CASE Tara Knowles Teller, individually and as Administrator of the Estate of Jax Teller, and as Next Friend for Abel Teller, (“Knowles-Teller”) filed a Complaint against Sons of Anarchy Trucking Empire, Inc. (“SOA”), a corporation incorporated in and with its principal place of business in the State of Lone Star. The Complaint alleged that Jax Teller (“Teller”) was driving in Charming, Lubbock County, State of Lone Star on April 4, 2020, when his motorcycle was struck by a semi-truck owned by SOA and driven by a SOA employee. Teller died in the accident. Knowles- Teller alleged that she was Teller’s wife, and that her son, Abel Teller., born January 8, 2021, is Teller’s son. Knowles-Teller Complaint alleged that SOA employees were negligent in driving the semi-truck in reverse on an access road to a freeway at a high rate of speed and without maintaining proper lookout. The Complaint also alleges that SOA was negligent in entrusting its vehicle to an employee who was not competent to drive the semi-truck. -

Men on Bikes the Outlaw As the New American Anti-Hero in Sons of Anarchy

Men on Bikes The Outlaw as the New American Anti-Hero in Sons of Anarchy Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Stephanie DIMAS am Institut für Amerikanistik Begutachter: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt Graz, 2017 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die den Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. Graz, im August 2017 Unterschrift: 2 Acknowledgement First of all, I want to thank my family (Mama, Wolfgang, Dimitri, Anna, Oma) for their endless support and understanding. I know it took me longer than expected, but you kept encouraging and believing in me. Noah, a very special thank you goes to you even though you are still too young to appreciate it. You came into all our lives as a blessing in more ways than one. Hopefully, you will want to read this one day. Thanks, Papa, for being the very first long-haired biker that I ever admired in my life. Next, I need to give a special thanks to my amazing friends (Angi, Julia, Silke) who gave me the time I needed and still managed to be there every step of the way. I could not have done it without your motivational speeches and helpful distractions. -

Criminal Heroes in Television: Exploring Moral Ambiguity in Law and Justice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wilfrid Laurier University Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2018 Criminal Heroes in Television: Exploring Moral Ambiguity in Law and Justice Amy Henry [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Criminology Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Amy, "Criminal Heroes in Television: Exploring Moral Ambiguity in Law and Justice" (2018). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 2105. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2105 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: MORAL AMBIGUITY IN LAW AND JUSTICE CRIMINAL HEROES IN TELEVISION: EXPLORING MORAL AMBIGUITY IN LAW AND JUSTICE by Amy Henry B.A. Honours Specialization Criminology Western University, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the Department of Criminology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts in Criminology Wilfrid Laurier University © Amy Henry 2018 ii MORAL AMBIGUITY IN LAW AND JUSTICE “Law and justice are not always the same. When they aren't, destroying the law may be the first step toward changing it.” ― Gloria Steinem (Grana, 2010) iii MORAL AMBIGUITY IN LAW AND JUSTICE Abstract Criminal justice is a popular theme in both news and entertainment media. How crime and justice issues are framed can actually legitimize corruption in a society. -

Last Call … a Fuzzy Peaches SOA Fanfiction 1

Last Call … A Fuzzy Peaches SOA Fanfiction 1 CHAPTER 1 "So … how's this? Does Mommy look hot?" Valerie asked, eyebrows raised, peering down at Mickey in his car seat. They'd pulled into a truck stop to freshen up. One thing Valerie had learned; truck stops really did have cleaner bathrooms compared to simple gas stations. And the roomiest stalls. She'd been able to close the toilet seat, set Mickey's car seat on it, and changed from shorts and a tank top to a turquoise sundress with plenty of room to move. Now she was at the sink, Mickey still seated next to her on the counter, chewing on a teething toy and just blinking at her. She's splashed water on her face, put her hair back in a headband, even put on lip gloss, touched up her deodorant and body spray. Overkill, maybe. But this road trip was ending at Teller-Morrow in Charming, and she wasn't leaving anything to chance. They were twenty minutes outside the little town she'd run from. Her stomach was turning, her nerves had her jumpy and anxious, and she felt totally guilty about keeping Mickey restrained in his car seat during this pit stop. But he hadn't messed himself, she'd changed him an hour before, and if she let him out he'd be all over, most likely digging his teething ring out of the toilet and shoving it back in his mouth. Yeah, that had happened once. He was a hellion, all over the place, and almost impossible to get under wraps once he was loose. -

'Sons of Anarchy' Star Ryan Hurst

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SONS OF ANARCHY’ STAR RYAN HURST COMING TO MOTOR CITY COMIC CON Special appearance on May 17th, May 18th, and 19th NOVI, MI. (January 14, 2019) – Motor City Comic Con, Michigan’s longest and largest comic and pop-culture event, is pleased to announce “Sons of Anarchy” star Ryan Hurst will attend this year’s convention on May 17th, 18th, and 19th at the Suburban Collection Showplace. Hurst will be hosting a panel Q&A and will be available for autographs and professional photo ops. Tickets are on sale now on the Motor City Comic Con website along with more information on pricing for autographs and photo ops. Ryan Hurst is an American actor, best known for his roles as Gerry Bertier in Disney’s “Remember the Titans”, Tom Clark in “Taken”, Opie Winston in the FX network drama series “Sons of Anarchy”, as Sergeant Ernie Savage in “We Were Soldiers”, as Chick in “Bates Motel”, and most recently announced as the newest villain “Beta” in ABC’s Walking Dead. This year will be monumental as Motor City Comic Con embarks on its 30th year and is expected to be the biggest convention in their history. Motor City Comic Con will utilize Suburban Collection Showplace’s newly expanded 180,000 square foot space by adding more events, exhibitors, media guests and comic guests as well as plans to introduce new concepts. Fans can expect to experience Sporcle trivia and Geek Speed Dating along with more exciting activities to be announced. This annual event attracts over 60,000 attendees each year with the opportunity to increase attendance for 2019.Fans can still expect all their traditional favorites such as Cosplay Contest with celebrity judges, an after-party on Saturday night and many kid- friendly activities. -

Yay Or Nay? a Media Analysis of How Deception Is Utilized As a Leadership Tactic in the Television Show Sons of Anarchy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 6-24-2020 Yay Or Nay? A Media Analysis Of How Deception Is Utilized As A Leadership Tactic In The Television Show Sons Of Anarchy Bruce T. Lanigan Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lanigan, Bruce T., "Yay Or Nay? A Media Analysis Of How Deception Is Utilized As A Leadership Tactic In The Television Show Sons Of Anarchy" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 1295. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1295 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YAY OR NAY? A MEDIA ANALYSIS OF HOW DECEPTION IS UTILIZED AS A LEADERSHIP TACTIC IN THE TELEVISION SHOW SONS OF ANARCHY Bruce T. Lanigan 101 Pages Individuals see deception on a daily basis. One of the places most people endure deception is in the workplace. This thesis analyzes how the television show Sons of Anarchy portrays deception by leaders in the workplace. Various story arcs portraying deceptive actions are analyzed through the lenses of leader-member exchange theory and interpersonal deception theory. This thesis encourages scholars to consider studying deception in terms of direct and indirect deception. Additionally, the findings reveal that Sons of Anarchy portrays that transformational leaders utilize deception more effectively while transactional leaders use deceptive measures more frequently. -

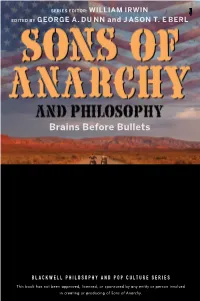

Brains Before Bullets

SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE Irwin EDITED BY George A. Du nn and J ason T. E berl Are we right to admire members of a criminal organization? Are the Sons of Anarchy really anarchists? How does their relationship to their bikes help to shape the Sons’ worldview? Do members of SAMCRO have the right to kill and make war? Does membership in the MC tend to foster virtue or vice? Do the club’s practices and moral code make it like a religion? FX’s hit television series Sons of Anarchy draws viewers into the morally ambiguous world of a close-knit outlaw motorcycle club, where standard social conventions and authority are shunned and replaced with a moral framework based on brotherhood, family, and community. It’s a violent and dangerous world where members frequently war with other outlaw groups and the federal government to protect their interests and those of their home base, the town of Charming, California. Featuring essays by philosophical fans of the show and drawing on the ideas of some of history’s greatest Brains Before Bullets philosophers, including Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Machiavelli, Hobbes, Marx, and Nietzsche, Sons of Anarchy and Philosophy examines the ethos of life in the MC, exploring the ethics of loyalty, honor, and revenge, individual and group identity, the morality of war and terrorism, religion, and the nature of political authority. Essential reading for fans of the show, this book takes readers deeper into the Sons of Anarchy Motorcycle Club, the Teller-Morrow family, and the ethics that surround their lives and activities. -

Virtue and Vice in the Samcropolis Aristotle Views Sons of Anarchy

Chapter 1 Virtue and Vice in the SAMCROpolis Aristotle Views Sons of Anarchy Jason T. Eberl At the end of Season 5 of Sons of Anarchy, just before she’s arrested as an accessory to murder, Tara informs Jax that she and their boys are leaving Charming. She doesn’t want her and Jax to “end up like the two people we hate the most”—Clay and Gemma Morrow—and their boys to be “destined to re-live all of our mistakes” (“J’ai Obtenu Cette”). Jax faces an ultimatum: either leave SAMCRO behind or lose his family. Less than two years earlier, after getting out of a three- month stint in Stockton prison, Jax had told Tara that he was done with SAMCRO and had made a deal with Clay to give him a way out. So Tara’s ultimatum should be a no-brainer for Jax, yet he seems torn. In the past several months, Jax has assumed the presidency of the MC and taken on more responsibility for the future direction of the club. But is his allegiance to the club and his sense of responsibility to its members—his brothers—the only thing holding him back from going to Oregon with his family? Could it be that he simply can’t bring himself to leave SAMCRO? After all, it’s the only life he’s ever known: “Since I was five, Tara, all I ever wanted was a Harley and a cut” (“Potlatch”). He has also confessed that, without SAMCRO, he’s just “an okay mechanic with a GED. -

Sons of Anarchy" Pilot GREEN Revision 06/16/08 1

TB Revised Pilot #179 Written by Kurt Sutter PRODUCTION Draft • 05/28/08 BLUE (FULL) Revision • 06/03/08 PINK (FULL) Revision • 06/10/08 YELLOW Revision • 06/11/08 GREEN Revision • 06/16/08 Story #: Revised Pilot Episode #179 Production #: 1WAB179 © 2008 Pacific 2.1 Entertainment Group, Inc. All rights reserved. TB “SON’S OF ANARCHY” PILOT Revision History PRODUCTION DRAFT (WHITE) 05/28/08 BLUE (Full) Revision 06/03/08 PINK (Full) Revision 06/10/08 YELLOW Revision 06/11/08 pp. 2, 3, 3A, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26 GREEN Revision 06/16/08 pp. 24, 26 TB “PILOT” CAST JAX TELLER ………………………………………………………… Charlie Hunnam CLAY TELLER ……………………………………………………… Ron Perlman GEMMA TELLER …………………………………………………… Katey Sagal TARA KNOWLES …………………………………………………… Maggie Siff BOBBY MUNSON …………………………………………………… Mark Boone Junior OPIE WINSTON …………………………………………………… Ryan Hurst CHIBS TELFORD ………………………………………………… Tommy Flanagan HALF-SACK EPPS ……………………………………………… Johnny Lewis TIG TRAGER ………………………………………………………… Kim Coates JUICE ORTIZ………………………………………………………… Theo Rossi PINEY WINSTON ………………………………………………… William Lucking WENDY CASE ………………………………………………………… Drea De Matteo HAPPY ……………………………………………………………………… David Labrava ERNEST DARBY …………………………………………………… Mitch Pileggi DONNA WINSTON…………………………………………………… Sprague Grayden CHIEF WAYNE UNSER ……………………………………… TBD MARCUS ALVAREZ ……………………………………………… Emilio Rivera SHERIFF VIC TRAMMEL ………………………………… Glenn Plummer SKEETER ………………………………………………………………… TBD LAROY ……………………………………………………………………… Tory Kittles LUANN DELANEY ………………………………………………… Dendrie Taylor LONG JOHN (HANG-AROUND)