Establishing Law and Order After Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law and Order

THE HAMLYN LECTURES Thirty-seventh series Law and Order Ralf Dahrendorf K.B.E., F.B.A. STEVENS Law and Order by Ralf Dahrendorf K.B.E., F.B.A. Professor of Social Science in the University of Constance; formerly Director of the London School of Economics In this book, based on his 1985 Hamlyn Lectures, Professor Ralf Dahrendorf considers the fundamental questions posed for the social order of free countries by the decline in respect for the law. Taking as his point of departure the terrors of our streets and the riots in our football grounds, Professor Dahrendorf discusses the implication for social order and liberty of such issues as unemployment, the cracks in the party system and the growing disorientation of the young. There are four major themes in the book— • The Road to Anomia—crime statistics are but the most dramatic symptoms of a loosening of social ties and norms. • Seeking Rousseau, Finding Hobbes—a widespread dream of goodness has resulted in the dismantling of some of the institutions designed to protect us from badness. • The Struggle for the Social Contract—underlying social changes have led from the class struggle to conflicts about the boundaries of society. • Society and Liberty—most reactions to the new condition involve threats to liberty—we need to reassert the links between law, order and liberty. Professor Dahrendorf has had a most distinguished career, both in his native Germany and in the United Kingdom. In Law and Order he offers a lively and stimulating analysis of a topic of vital importance in the life of every citizen. -

B Workshop Papers and Highlights

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. S. Department of Justice ce of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice INational Institute of Justice I Policingin Emerging Democracies: b WorkshopPapers and Highlights P_ National Institute of Justice U.S. Department of Justice ,g Bureau of International Narcotics Ir and Law Enforcement Affairs U.S. Department of State I rares o~ I I Washington, D.C., December 14-15,1995 I I I I I I U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs I 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 I Janet Reno Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice I John C. Dwyer Acting Associate Attorney General I Laurie Robinson Assistant Atto~tey General I Jeremy Travis Director, National Institute of Justice Justice Information Center i World Wide Web Site http.'l/www, ncjrs, org I Opinions or points of view expressed in this document are those of the authors and I do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice. The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice i Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. I NCJ 167024 I I I I I Policingin Emerging Democracies: m Workshop Papers and Highlights I I National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice I I I Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, U.S. -

A Gold-Colored Rose

Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer – Editor: Brent Manley – Assistant Editors: Mark Horton, Brian Senior & Franco Broccoli – Layout Editor: Akis Kanaris – Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue No. 13 Thursday, 22 June 2006 A Gold-Colored Rose VuGraph Programme Teatro Verdi 10.30 Open Pairs Final 1 15.45 Open Pairs Final 2 TODAY’S PROGRAMME Open and Women’s Pairs (Final) 10.30 Session 1 15.45 Session 2 Rosenblum winners: the Rose Meltzer team IMP Pairs 10.30 Final A, Final B - Session 1 In 2001, Geir Helgemo and Tor Helness were on the Nor- 15.45 Final A, Final B - Session 2 wegian team that lost to Rose Meltzer's squad in the Bermu- Senior Pairs da Bowl. In Verona, they joined Meltzer, Kyle Larsen,Alan Son- 10.30 Session 5 tag and Roger Bates to earn their first world championship – 15.45 Session 6 the Rosenblum Cup. It wasn't easy, as the valiant team captained by Christal Hen- ner-Welland team mounted a comeback toward the end of Contents the 64-board match that had Meltzer partisans worried.The rally fizzled out, however, and Meltzer won handily, 179-133. Results . 2-6 The bronze medal went to Yadlin, 69-65 winners over Why University Bridge? . .7 Welland in the play-off. Left out of yesterday's report were Osservatorio . .8 the McConnell bronze medallists – Katt-Bridge, 70-67 win- Championship Diary . .9 ners over China Global Times. Comeback Time . .10 As the tournament nears its conclusion, the pairs events are The Playing World Represented by Precious Cartier Jewels . -

USA Recapture Mcconnell Cup

Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer (France) Issue: 12 Chief Editor: Mark Horton (England) Editors: Brent Manley (USA), Brian Senior (England) Layout Editor: George Hatzidakis (Greece) Photographer: Ron Tacchi (England) 28th August 2002 USA recapture McConnell Cup ATTENTION!!! All events begin at 10.00 Open and Women's Pairs 152 pairs play in the Open Pairs Semi-final. Approxi- mately 66 of these will qualify for the final, where about six more pairs are expected to drop in from the Rosenblum semi-finals and final to make a 72-pair final. An American team won the inaugural McConnell Cup 52 pairs play in the Women's Pairs Semi-final.We ex- contest in Albuquerque in 1994 and now eight years pect 21 to qualify for the final, with another 11 pairs later the trophy returns to its native soil.The all Amer- joining them from the McConnell semi-finals and final ican final saw Irina Levitina, Kerri Sanborn, Lynn Deas, to make a field of 32 pairs for the final. Beth Palmer, Randi Montin and Jill Meyers (pictured Both finals will be played over five sessions commenc- above) comfortably outscore Judi Radin, Shawn Quinn, ing on Thursday morning at 10.00 a.m. Mildred Breed, Rozanne Pollack, Hjordis Eythorsdottir and Valerie Westheimer. Seniors Pairs In the Power Rosenblum, after two scintillating semi fi- There are 72 pairs playing in the Seniors Pairs Qualify- nals, Lavazza meet Munawar in today's final. ing stage, of which 28 will go through to the final.This is a three-session event that starts at 10.00 a.m. -

Development Ofmonitoring Instruments Forjudicial and Law

Background Research on Systems and Context on Systems Research Background Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement institutions in the Western Balkans Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans 2009 - 2011 CARDS Regional Action Programme With funding by the European Commission April 2010 Disclaimers This Report has not been formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Comments on this report are welcome and can be sent to: Statistics and Survey Section United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 5475 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 7 5475 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org 1 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context 2 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans April 2010 3 Acknowledgements Funding for this report was provided by the European Commission under the CARDS 2006 Regional Action Programme. This report was produced under the responsibility of Statistics and Surveys Section (SASS) and Regional Programme Office for South Eastern Europe (RPOSEE) of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) based on research conducted by the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). -

ICITAP's IT & Border Security Systems Expertise

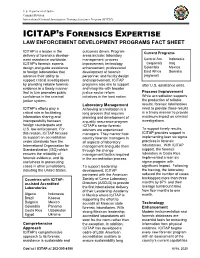

U.S. Department of Justice Criminal Division International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP) ICITAP’S FORENSICS EXPERTISE LAW ENFORCEMENT DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS FACT SHEET ICITAP is a leader in the outcomes driven. Program Current Programs delivery of forensics develop- areas include: laboratory ment assistance worldwide. management; process Central Am. Indonesia ICITAP’s forensic experts improvement; technology (regional) Iraq design and guide assistance enhancement; professional Colombia Mexico to foreign laboratories that development of forensic East Africa Somalia advance their ability to personnel; and facility design (regional) support critical investigations and improvement. ICITAP by providing reliable forensic programs also aim to support after U.S. assistance ends. evidence in a timely manner and integrate with broader that in turn promotes public justice sector reform Process Improvement confidence in the criminal initiatives in the host nation. While accreditation supports justice system. the production of reliable Laboratory Management results, forensic laboratories ICITAP’s efforts play a Achieving accreditation is a need to provide those results critical role in facilitating long process that requires in a timely manner to provide information sharing and planning and development of maximum impact on criminal interoperability between a quality assurance program. investigations. foreign counterparts and ICITAP’s senior forensic U.S. law enforcement. For advisors are experienced To support timely results, this reason, ICITAP focuses managers. They mentor host ICITAP provides support in its support on accreditation country forensic managers in implementing lean six sigma under standards from the all aspects of laboratory practices in forensic International Organization for management and guide them laboratories. With ICITAP Standardization (ISO) which through the change support, the forensic ensures the reliability of management tactics required laboratory in Costa Rica forensic evidence, and its in the accreditation process. -

BULLETIN Editorial

THE INTERNATIONAL BRIDGE PRESS ASSOCIATION Editor: John Carruthers This Bulletin is published monthly and circulated to around 400 members of the International Bridge Press Association comprising the world’s leading journalists, authors and editors of news, books and articles about contract bridge, with an estimated readership of some 200 million people BULLETIN who enjoy the most widely played of all card games. www.ibpa.com No. 563 Year 2011 Date December 10 President: PATRICK D JOURDAIN Editorial 8 Felin Wen, Rhiwbina ACBL tournaments are noted for their ability to handle walk-up entries, even in elite Cardiff CF14 6NW, WALES UK (44) 29 2062 8839 events with hundreds of tables. Only events which require seeding of teams require [email protected] some sort of pre-tournament entry. For all other events, entries are accepted up until Chairman: game time. PER E JANNERSTEN Nevertheless, there are some areas that can be improved upon and these were evident Banergatan 15 SE-752 37 Uppsala, SWEDEN in Seattle at the Fall NABC. The first was in broadcasting the events over BBO. The main (46) 18 52 13 00 events at the Fall Nationals are the Reisinger, the Blue Ribbon Pairs (each three days in [email protected] length), the Open Teams (Board-a-Match) and the Open Pairs (each two days long). Executive Vice-President: There are also big events for seniors, juniors and women, the biggest of which is the JAN TOBIAS van CLEEFF Senior Knockout Teams. So we had ten days of top-flight competition – unfortunately, Prinsegracht 28a only three days’ worth was broadcast on BBO (semifinals, one match only, and finals of 2512 GA The Hague, NETHERLANDS the Senior KO and the third day of the Reisinger). -

Crime, 1966-1967

The original documents are located in Box D6, folder “Ford Press Releases - Crime, 1966- 1967 (2)” of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. The Council donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box D6 of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library CONGRESSMAN NEWS GERALD R. FORD HOUSE REPUBLICAN LEADER RELEASE ••Release in PMs of August 3-- Remarks by Rep. Gerald R. Ford, R-Mich., prepared for delivery on the floor of the House on Thursday, August 3, 1967. Mr. Speaker, America today is shaken by a deep national crisis--a near- breakdown of law and order made even more severe by civil disorders in which criminal elements are heavily engaged. The law-abiding citizens of America who have suffered at the hands of the lawless and the extremists are anxiously awaiting a remedy. This is a time for swift and decisive acti~n. -

Educating Toto Test Your Technique the Rabbit's Sticky Wicket

A NEW BRIDGE MAGAZINE The Rabbit’s Sticky Wicket Test Your Technique Educating Toto EDITION 22 October 2019 A NEW BRIDGE MAGAZINE – OCTOBER 2019 The State of the Union announcement of the Writing on its web site, the Chairman of the start of an U31 series English Bridge Union rightly pays tribute to the as from next year. performance of the English teams in the recently Funding these brings concluded World Championships in Wuhan. He a greater burden on A NEW concludes with the sentence: All in all an excel- the membership and lent performance and one I think the membership the current desire of will join with me in saying well done to our teams. the WBF to hold many events in China means If the EBU believe the membership takes pride that travel costs are high. The EBU expects to in the performance of its teams at international support international teams but not without level it is difficult to understand the decision to limit. That is, after all, one reason for its exist- BRIDGE withdraw financial support for English teams ence. We expect to continue to support junior hoping to compete in the World Bridge Games events into the future. We also expect to support MAGAZINE in 2020. (They will still pay the entry fees). They Editor: all our teams to at least some extent. Sometimes will continue to support some of the teams that is entry fee and uniform costs only. That is Mark Horton competing in the European Championships in true, for example of the Mixed series introduced Advertising: Madeira in 2020, but because it will now be eas- last year. -

The-Encyclopedia-Of-Cardplay-Techniques-Guy-Levé.Pdf

© 2007 Guy Levé. All rights reserved. It is illegal to reproduce any portion of this mate- rial, except by special arrangement with the publisher. Reproduction of this material without authorization, by any duplication process whatsoever, is a violation of copyright. Master Point Press 331 Douglas Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5M 1H2 (416) 781-0351 Website: http://www.masterpointpress.com http://www.masteringbridge.com http://www.ebooksbridge.com http://www.bridgeblogging.com Email: [email protected] Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Levé, Guy The encyclopedia of card play techniques at bridge / Guy Levé. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55494-141-4 1. Contract bridge--Encyclopedias. I. Title. GV1282.22.L49 2007 795.41'5303 C2007-901628-6 Editor Ray Lee Interior format and copy editing Suzanne Hocking Cover and interior design Olena S. Sullivan/New Mediatrix Printed in Canada by Webcom Ltd. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08 07 Preface Guy Levé, an experienced player from Montpellier in southern France, has a passion for bridge, particularly for the play of the cards. For many years he has been planning to assemble an in-depth study of all known card play techniques and their classification. The only thing he lacked was time for the project; now, having recently retired, he has accom- plished his ambitious task. It has been my privilege to follow its progress and watch the book take shape. A book such as this should not to be put into a beginner’s hands, but it should become a well-thumbed reference source for all players who want to improve their game. -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm.