Week 3: Differential Geometry of Curves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This Course Is an Introduction to the Geometry of Smooth Curves and Surf

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This course is an introduction to the geometry of smooth if the velocity never vanishes). Then the speed is a (smooth) curves and surfaces in Euclidean space Rn (in particular for positive function of t. (The cusped curve β above is not regular n = 2; 3). The local shape of a curve or surface is described at t = 0; the other examples given are regular.) in terms of its curvatures. Many of the big theorems in the DE The lengthR [ : Länge] of a smooth curve α is defined as subject – such as the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, a highlight at the j j len(α) = I α˙(t) dt. (For a closed curve, of course, we should end of the semester – deal with integrals of curvature. Some integrate from 0 to T instead of over the whole real line.) For of these integrals are topological constants, unchanged under any subinterval [a; b] ⊂ I, we see that deformation of the original curve or surface. Z b Z b We will usually describe particular curves and surfaces jα˙(t)j dt ≥ α˙(t) dt = α(b) − α(a) : locally via parametrizations, rather than, say, as level sets. a a Whereas in algebraic geometry, the unit circle is typically be described as the level set x2 + y2 = 1, we might instead This simply means that the length of any curve is at least the parametrize it as (cos t; sin t). straight-line distance between its endpoints. Of course, by Euclidean space [DE: euklidischer Raum] The length of an arbitrary curve can be defined (following n we mean the vector space R 3 x = (x1;:::; xn), equipped Jordan) as its total variation: with with the standard inner product or scalar product [DE: P Xn Skalarproduktp ] ha; bi = a · b := aibi and its associated norm len(α):= TV(α):= sup α(ti) − α(ti−1) : jaj := ha; ai. -

The Osculating Circumference Problem

THE OSCULATING CIRCUMFERENCE PROBLEM School I.S.I.S.S. M. Casagrande Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Students Silvia Micheletto (I) Azzurra Soa Pizzolotto (IV) Luca Barisan (II) Simona Sota (IV) Gaia Barella (IV) Paolo Barisan (V) Marco Casagrande (IV) Anna De Biasi (V) Chiara De Rosso (IV) Silvia Giovani (V) Maddalena Favaro (IV) Klara Metaliu (V) Teachers Fabio Breda Francesco Maria Cardano Davide Palma Francesco Zampieri Researcher Alberto Zanardo, University of Padova Italy Year 2019/2020 The osculating circumference problem ISISS M. Casagrande, Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Abstract The aim of the article is to study the osculating circumference i.e. the circumference which best approximates the graph of a curve at one of its points. We will dene this circumference and we will describe several methods to nd it. Finally we will introduce the notions of round points and crossing points, points of the curve where the circumference has interesting properties. ??? Contents Introduction 3 1 The osculating circumference 5 1.1 Particular cases: the formulas cannot be applied . 9 1.2 Curvature . 14 2 Round points 15 3 Beyond round points 22 3.1 Crossing points . 23 4 Osculating circumference of a conic section 25 4.1 The rst method . 25 4.2 The second method . 26 References 31 2 The osculating circumference problem ISISS M. Casagrande, Pieve di Soligo, Treviso Italy Introduction Our research was born from an analytic geometry problem studied during the third year of high school. The problem. Let P : y = x2 be a parabola and A and B two points of the curve symmetrical about the axis of the parabola. -

Plotting Graphs of Parametric Equations

Parametric Curve Plotter This Java Applet plots the graph of various primary curves described by parametric equations, and the graphs of some of the auxiliary curves associ- ated with the primary curves, such as the evolute, involute, parallel, pedal, and reciprocal curves. It has been tested on Netscape 3.0, 4.04, and 4.05, Internet Explorer 4.04, and on the Hot Java browser. It has not yet been run through the official Java compilers from Sun, but this is imminent. It seems to work best on Netscape 4.04. There are problems with Netscape 4.05 and it should be avoided until fixed. The applet was developed on a 200 MHz Pentium MMX system at 1024×768 resolution. (Cost: $4000 in March, 1997. Replacement cost: $695 in June, 1998, if you can find one this slow on sale!) For various reasons, it runs extremely slowly on Macintoshes, and slowly on Sun Sparc stations. The curves should move as quickly as Roadrunner cartoons: for a benchmark, check out the circular trigonometric diagrams on my Java page. This applet was mainly done as an exercise in Java programming leading up to more serious interactive animations in three-dimensional graphics, so no attempt was made to be comprehensive. Those who wish to see much more comprehensive sets of curves should look at: http : ==www − groups:dcs:st − and:ac:uk= ∼ history=Java= http : ==www:best:com= ∼ xah=SpecialP laneCurve dir=specialP laneCurves:html http : ==www:astro:virginia:edu= ∼ eww6n=math=math0:html Disclaimer: Like all computer graphics systems used to illustrate mathematical con- cepts, it cannot be error-free. -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

Design Data 21

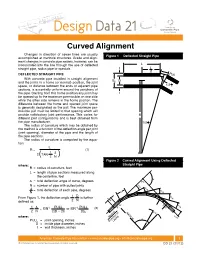

Design Data 21 Curved Alignment Changes in direction of sewer lines are usually Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe accomplished at manhole structures. Grade and align- Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe ment changes in concrete pipe sewers, however, can be incorporated into the line through the use of deflected L straight pipe, radius pipe or specials. t L 2 DEFLECTED STRAIGHT PIPE Pull With concrete pipe installed in straight alignment Bc D and the joints in a home (or normal) position, the joint ∆ space, or distance between the ends of adjacent pipe 1/2 N sections, is essentially uniform around the periphery of the pipe. Starting from this home position any joint may t be opened up to the maximum permissible on one side while the other side remains in the home position. The difference between the home and opened joint space is generally designated as the pull. The maximum per- missible pull must be limited to that opening which will provide satisfactory joint performance. This varies for R different joint configurations and is best obtained from the pipe manufacturer. ∆ 1/2 N The radius of curvature which may be obtained by this method is a function of the deflection angle per joint (joint opening), diameter of the pipe and the length of the pipe sections. The radius of curvature is computed by the equa- tion: L R = (1) 1 ∆ 2 TAN ( 2 N ) Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected where: Straight Pipe R = radius of curvature, feet Straight Pipe L = length of pipe sections measured along the centerline, feet ∆ ∆ = total deflection angle of curve, degrees P.I. -

Radius-Of-Curvature.Pdf

CHAPTER 5 CURVATURE AND RADIUS OF CURVATURE 5.1 Introduction: Curvature is a numerical measure of bending of the curve. At a particular point on the curve , a tangent can be drawn. Let this line makes an angle Ψ with positive x- axis. Then curvature is defined as the magnitude of rate of change of Ψ with respect to the arc length s. Ψ Curvature at P = It is obvious that smaller circle bends more sharply than larger circle and thus smaller circle has a larger curvature. Radius of curvature is the reciprocal of curvature and it is denoted by ρ. 5.2 Radius of curvature of Cartesian curve: ρ = = (When tangent is parallel to x – axis) ρ = (When tangent is parallel to y – axis) Radius of curvature of parametric curve: ρ = , where and – Example 1 Find the radius of curvature at any pt of the cycloid , – Solution: Page | 1 – and Now ρ = = – = = =2 Example 2 Show that the radius of curvature at any point of the curve ( x = a cos3 , y = a sin3 ) is equal to three times the lenth of the perpendicular from the origin to the tangent. Solution : – – – = – 3a [–2 cos + ] 2 3 = 6 a cos sin – 3a cos = Now = – = Page | 2 = – – = – – = = 3a sin …….(1) The equation of the tangent at any point on the curve is 3 3 y – a sin = – tan (x – a cos ) x sin + y cos – a sin cos = 0 ……..(2) The length of the perpendicular from the origin to the tangent (2) is – p = = a sin cos ……..(3) Hence from (1) & (3), = 3p Example 3 If & ' are the radii of curvature at the extremities of two conjugate diameters of the ellipse = 1 prove that Solution: Parametric equation of the ellipse is x = a cos , y=b sin = – a sin , = b cos = – a cos , = – b sin The radius of curvature at any point of the ellipse is given by = = – – – – – Page | 3 = ……(1) For the radius of curvature at the extremity of other conjugate diameter is obtained by replacing by + in (1). -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (Or Leibniz) Was Born at Leipzig on June 21 (O.S.), 1646, and Died in Hanover on November 14, 1716. H

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz (or Leibniz) was born at Leipzig on June 21 (O.S.), 1646, and died in Hanover on November 14, 1716. His father died before he was six, and the teaching at the school to which he was then sent was inefficient, but his industry triumphed over all difficulties; by the time he was twelve he had taught himself to read Latin easily, and had begun Greek; and before he was twenty he had mastered the ordinary text-books on mathematics, philosophy, theology and law. Refused the degree of doctor of laws at Leipzig by those who were jealous of his youth and learning, he moved to Nuremberg. An essay which there wrote on the study of law was dedicated to the Elector of Mainz, and led to his appointment by the elector on a commission for the revision of some statutes, from which he was subsequently promoted to the diplomatic service. In the latter capacity he supported (unsuccessfully) the claims of the German candidate for the crown of Poland. The violent seizure of various small places in Alsace in 1670 excited universal alarm in Germany as to the designs of Louis XIV.; and Leibnitz drew up a scheme by which it was proposed to offer German co-operation, if France liked to take Egypt, and use the possessions of that country as a basis for attack against Holland in Asia, provided France would agree to leave Germany undisturbed. This bears a curious resemblance to the similar plan by which Napoleon I. proposed to attack England. In 1672 Leibnitz went to Paris on the invitation of the French government to explain the details of the scheme, but nothing came of it. -

Geometry in the Age of Enlightenment

Geometry in the Age of Enlightenment Raymond O. Wells, Jr. ∗ July 2, 2015 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Algebraic Geometry 3 2.1 Algebraic Curves of Degree Two: Descartes and Fermat . 5 2.2 Algebraic Curves of Degree Three: Newton and Euler . 11 3 Differential Geometry 13 3.1 Curvature of curves in the plane . 17 3.2 Curvature of curves in space . 26 3.3 Curvature of a surface in space: Euler in 1767 . 28 4 Conclusion 30 1 Introduction The Age of Enlightenment is a term that refers to a time of dramatic changes in western society in the arts, in science, in political thinking, and, in particular, in philosophical discourse. It is generally recognized as being the period from the mid 17th century to the latter part of the 18th century. It was a successor to the renaissance and reformation periods and was followed by what is termed the romanticism of the 19th century. In his book A History of Western Philosophy [25] Bertrand Russell (1872{1970) gives a very lucid description of this time arXiv:1507.00060v1 [math.HO] 30 Jun 2015 period in intellectual history, especially in Book III, Chapter VI{Chapter XVII. He singles out Ren´eDescartes as being the founder of the era of new philosophy in 1637 and continues to describe other philosophers who also made significant contributions to mathematics as well, such as Newton and Leibniz. This time of intellectual fervor included literature (e.g. Voltaire), music and the world of visual arts as well. One of the most significant developments was perhaps in the political world: here the absolutism of the church and of the monarchies ∗Jacobs University Bremen; University of Colorado at Boulder; [email protected] 1 were questioned by the political philosophers of this era, ushering in the Glo- rious Revolution in England (1689), the American Revolution (1776), and the bloody French Revolution (1789). -

An Easier Derivation of the Curvature Formula from First Principles

An easier derivation of the curvature formula from first principles Robert Ferguson Florida, USA bobferg13@comcast .net Introduction he radius of curvature formula is usually introduced in a university calculus Tcourse. Its proof is not included in most high school calculus courses and even some first-year university calculus courses because many students find the calculus used difficult (see Larson, Hostetler & Edwards, 2007, pp. 870– 872). Fortunately, there is an easier way to motivate and prove the radius of curvature formula without using formal calculus. An additional benefit is that the proof provides the coordinates of the centre of the corresponding circle of curvature. Understanding the proof requires only what advanced high school students already know: e.g., algebra, a little geometry about circles, and the intuition that both a circle and a curve have a slope and curvature. The proof is suitable for first-year university and advanced high school students. In terms of algebra, students need to know how to solve two simultaneous linear equations with two unknowns. In terms of geometry, students need to know that: 1. The radius of a circle drawn to a point of tangency between the circle and a tangent line is perpendicular to the tangent line. 2. If two separate lines are tangent to a circle at two different points, the lines drawn perpendicular to the tangent lines at their points of tangency intersect each other at the circle’s centre. 3. Each perpendicular line’s segment from its point of tangency to the point of intersection is a radius. The paper’s development of the radius of curvature formula can be used as an insightful application of the mathematics advanced high school students already know. -

Differential Calculus—I

UNIT I Differential Calculus—I 1.1 INTRODUCTION In many practical situations engineers and scientists come across problems which involve quantities of varying nature. Calculus in general, and differential calculus in particular, provide the analyst with several mathematical tools and techniques in studying how the functions involved in the problem behave. The student may recall at this stage that the derivative, obtained through the basic operation of calculus, called differentiation, measures the rate of change of the functions (dependent variable) with respect to the independent variable. In this chapter we examine how the concept of the derivative can be adopted in the study of curvedness or bending of curves. 1.2 RADIUS OF CURVATURE Let P be any point on the curve C. Draw the tangent at P to the Y C circle. The circle having the same curvature as the curve at P touching the curve at P, is called the circle of curvature. It is also O called the osculating circle. The centre of the circle of the cur- vature is called the centre of curvature. The radius of the circle P of curvature is called the radius of curvature and is denoted by ‘ρ’. Note : 1. If k (> 0) is the curvature of a curve at P, then the radius O X 1 of curvature of the curve of ρ is . This follows from the definition k Fig. 1.1 of radius of curvature and the result that the curvature of a circle is the reciprocal of its radius. dψ Note : 2. If for an arc of a curve, ψ decreases as s increases, then is negative, i.e., k is negative. -

Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces 1

DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY OF CURVES AND SURFACES 1. Curves in the Plane 1.1. Points, Vectors, and Their Coordinates. Points and vectors are fundamental objects in Geometry. The notion of point is intuitive and clear to everyone. The notion of vector is a bit more delicate. In fact, rather than saying what a vector is, we prefer to say what a vector has, namely: direction, sense, and length (or magnitude). It can be represented by an arrow, and the main idea is that two arrows represent the same vector if they have the same direction, sense, and length. An arrow representing a vector has a tail and a tip. From the (rough) definition above, we deduce that in order to represent (if you want, to draw) a given vector as an arrow, it is necessary and sufficient to prescribe its tail. a c b b a c a a b P Figure 1. We see four copies of the vector a, three of the vector b, and two of the vector c. We also see a point P . An important instrument in handling points, vectors, and (consequently) many other geometric objects is the Cartesian coordinate system in the plane. This consists of a point O, called the origin, and two perpendicular lines going through O, called coordinate axes. Each line has a positive direction, indicated by an arrow (see Figure 2). We denote by R the a P y a y x O O x Figure 2. The point P has coordinates x, y. The vector a has also coordinates x, y. -

Osculating Curves and Surfaces*

OSCULATING CURVES AND SURFACES* BY PHILIP FRANKLIN 1. Introduction The limit of a sequence of curves, each of which intersects a fixed curve in « +1 distinct points, which close down to a given point in the limit, is a curve having contact of the «th order with the fixed curve at the given point. If we substitute surface for curve in the above statement, the limiting surface need not osculate the fixed surface, no matter what value » has, unless the points satisfy certain conditions. We shall obtain such conditions on the points, our conditions being necessary and sufficient for contact of the first order, and sufficient for contact of higher order. By taking as the sequence of curves parabolas of the «th order, we obtain theorems on the expression of the »th derivative of a function at a point as a single limit. For the surfaces, we take paraboloids of high order, and obtain such expressions for the partial derivatives. In this case, our earlier restriction, or some other, on the way in which the points close down to the limiting point is necessary. In connection with our discussion of osculating curves, we obtain some interesting theorems on osculating conies, or curves of any given type, which follow from a generalization of Rolle's theorem on the derivative to a theorem on the vanishing of certain differential operators. 2. Osculating curves Our first results concerning curves are more or less well known, and are presented chiefly for the sake of completeness and to orient the later results, t We begin with a fixed curve c, whose equation, in some neighbor- hood of the point x —a, \x —a\<Q, may be written y=f(x).