Differential Geometry Motivation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polar Coordinates, Arc Length and the Lemniscate Curve

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Calculus Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Summer 2018 Gaussian Guesswork: Polar Coordinates, Arc Length and the Lemniscate Curve Janet Heine Barnett Colorado State University-Pueblo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Barnett, Janet Heine, "Gaussian Guesswork: Polar Coordinates, Arc Length and the Lemniscate Curve" (2018). Calculus. 3. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_calculus/3 This Course Materials is brought to you for free and open access by the Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Calculus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gaussian Guesswork: Polar Coordinates, Arc Length and the Lemniscate Curve Janet Heine Barnett∗ October 26, 2020 Just prior to his 19th birthday, the mathematical genius Carl Freidrich Gauss (1777{1855) began a \mathematical diary" in which he recorded his mathematical discoveries for nearly 20 years. Among these discoveries is the existence of a beautiful relationship between three particular numbers: • the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, or π; Z 1 dx • a specific value of a certain (elliptic1) integral, which Gauss denoted2 by $ = 2 p ; and 4 0 1 − x p p • a number called \the arithmetic-geometric mean" of 1 and 2, which he denoted as M( 2; 1). Like many of his discoveries, Gauss uncovered this particular relationship through a combination of the use of analogy and the examination of computational data, a practice that historian Adrian Rice called \Gaussian Guesswork" in his Math Horizons article subtitled \Why 1:19814023473559220744 ::: is such a beautiful number" [Rice, November 2009]. -

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This Course Is an Introduction to the Geometry of Smooth Curves and Surf

J.M. Sullivan, TU Berlin A: Curves Diff Geom I, SS 2019 This course is an introduction to the geometry of smooth if the velocity never vanishes). Then the speed is a (smooth) curves and surfaces in Euclidean space Rn (in particular for positive function of t. (The cusped curve β above is not regular n = 2; 3). The local shape of a curve or surface is described at t = 0; the other examples given are regular.) in terms of its curvatures. Many of the big theorems in the DE The lengthR [ : Länge] of a smooth curve α is defined as subject – such as the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, a highlight at the j j len(α) = I α˙(t) dt. (For a closed curve, of course, we should end of the semester – deal with integrals of curvature. Some integrate from 0 to T instead of over the whole real line.) For of these integrals are topological constants, unchanged under any subinterval [a; b] ⊂ I, we see that deformation of the original curve or surface. Z b Z b We will usually describe particular curves and surfaces jα˙(t)j dt ≥ α˙(t) dt = α(b) − α(a) : locally via parametrizations, rather than, say, as level sets. a a Whereas in algebraic geometry, the unit circle is typically be described as the level set x2 + y2 = 1, we might instead This simply means that the length of any curve is at least the parametrize it as (cos t; sin t). straight-line distance between its endpoints. Of course, by Euclidean space [DE: euklidischer Raum] The length of an arbitrary curve can be defined (following n we mean the vector space R 3 x = (x1;:::; xn), equipped Jordan) as its total variation: with with the standard inner product or scalar product [DE: P Xn Skalarproduktp ] ha; bi = a · b := aibi and its associated norm len(α):= TV(α):= sup α(ti) − α(ti−1) : jaj := ha; ai. -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

NOTES Reconsidering Leibniz's Analytic Solution of the Catenary

NOTES Reconsidering Leibniz's Analytic Solution of the Catenary Problem: The Letter to Rudolph von Bodenhausen of August 1691 Mike Raugh January 23, 2017 Leibniz published his solution of the catenary problem as a classical ruler-and-compass con- struction in the June 1691 issue of Acta Eruditorum, without comment about the analysis used to derive it.1 However, in a private letter to Rudolph Christian von Bodenhausen later in the same year he explained his analysis.2 Here I take up Leibniz's argument at a crucial point in the letter to show that a simple observation leads easily and much more quickly to the solution than the path followed by Leibniz. The argument up to the crucial point affords a showcase in the techniques of Leibniz's calculus, so I take advantage of the opportunity to discuss it in the Appendix. Leibniz begins by deriving a differential equation for the catenary, which in our modern orientation of an x − y coordinate system would be written as, dy n Z p = (n = dx2 + dy2); (1) dx a where (x; z) represents cartesian coordinates for a point on the catenary, n is the arc length from that point to the lowest point, the fraction on the left is a ratio of differentials, and a is a constant representing unity used throughout the derivation to maintain homogeneity.3 The equation characterizes the catenary, but to solve it n must be eliminated. 1Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm, \De linea in quam flexile se pondere curvat" in Die Mathematischen Zeitschriftenartikel, Chap 15, pp 115{124, (German translation and comments by Hess und Babin), Georg Olms Verlag, 2011. -

The Arc Length of a Random Lemniscate

The arc length of a random lemniscate Erik Lundberg, Florida Atlantic University joint work with Koushik Ramachandran [email protected] SEAM 2017 Random lemniscates Topic of my talk last year at SEAM: Random rational lemniscates on the sphere. Topic of my talk today: Random polynomial lemniscates in the plane. Polynomial lemniscates: three guises I Complex Analysis: pre-image of unit circle under polynomial map jp(z)j = 1 I Potential Theory: level set of logarithmic potential log jp(z)j = 0 I Algebraic Geometry: special real-algebraic curve p(x + iy)p(x + iy) − 1 = 0 Polynomial lemniscates: three guises I Complex Analysis: pre-image of unit circle under polynomial map jp(z)j = 1 I Potential Theory: level set of logarithmic potential log jp(z)j = 0 I Algebraic Geometry: special real-algebraic curve p(x + iy)p(x + iy) − 1 = 0 Polynomial lemniscates: three guises I Complex Analysis: pre-image of unit circle under polynomial map jp(z)j = 1 I Potential Theory: level set of logarithmic potential log jp(z)j = 0 I Algebraic Geometry: special real-algebraic curve p(x + iy)p(x + iy) − 1 = 0 Prevalence of lemniscates I Approximation theory: Hilbert's lemniscate theorem I Conformal mapping: Bell representation of n-connected domains I Holomorphic dynamics: Mandelbrot and Julia lemniscates I Numerical analysis: Arnoldi lemniscates I 2-D shapes: proper lemniscates and conformal welding I Harmonic mapping: critical sets of complex harmonic polynomials I Gravitational lensing: critical sets of lensing maps Prevalence of lemniscates I Approximation theory: -

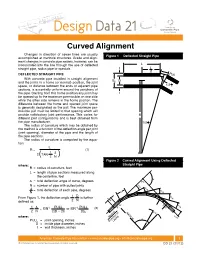

Design Data 21

Design Data 21 Curved Alignment Changes in direction of sewer lines are usually Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe accomplished at manhole structures. Grade and align- Figure 1 Deflected Straight Pipe ment changes in concrete pipe sewers, however, can be incorporated into the line through the use of deflected L straight pipe, radius pipe or specials. t L 2 DEFLECTED STRAIGHT PIPE Pull With concrete pipe installed in straight alignment Bc D and the joints in a home (or normal) position, the joint ∆ space, or distance between the ends of adjacent pipe 1/2 N sections, is essentially uniform around the periphery of the pipe. Starting from this home position any joint may t be opened up to the maximum permissible on one side while the other side remains in the home position. The difference between the home and opened joint space is generally designated as the pull. The maximum per- missible pull must be limited to that opening which will provide satisfactory joint performance. This varies for R different joint configurations and is best obtained from the pipe manufacturer. ∆ 1/2 N The radius of curvature which may be obtained by this method is a function of the deflection angle per joint (joint opening), diameter of the pipe and the length of the pipe sections. The radius of curvature is computed by the equa- tion: L R = (1) 1 ∆ 2 TAN ( 2 N ) Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected Figure 2 Curved Alignment Using Deflected where: Straight Pipe R = radius of curvature, feet Straight Pipe L = length of pipe sections measured along the centerline, feet ∆ ∆ = total deflection angle of curve, degrees P.I. -

Radius-Of-Curvature.Pdf

CHAPTER 5 CURVATURE AND RADIUS OF CURVATURE 5.1 Introduction: Curvature is a numerical measure of bending of the curve. At a particular point on the curve , a tangent can be drawn. Let this line makes an angle Ψ with positive x- axis. Then curvature is defined as the magnitude of rate of change of Ψ with respect to the arc length s. Ψ Curvature at P = It is obvious that smaller circle bends more sharply than larger circle and thus smaller circle has a larger curvature. Radius of curvature is the reciprocal of curvature and it is denoted by ρ. 5.2 Radius of curvature of Cartesian curve: ρ = = (When tangent is parallel to x – axis) ρ = (When tangent is parallel to y – axis) Radius of curvature of parametric curve: ρ = , where and – Example 1 Find the radius of curvature at any pt of the cycloid , – Solution: Page | 1 – and Now ρ = = – = = =2 Example 2 Show that the radius of curvature at any point of the curve ( x = a cos3 , y = a sin3 ) is equal to three times the lenth of the perpendicular from the origin to the tangent. Solution : – – – = – 3a [–2 cos + ] 2 3 = 6 a cos sin – 3a cos = Now = – = Page | 2 = – – = – – = = 3a sin …….(1) The equation of the tangent at any point on the curve is 3 3 y – a sin = – tan (x – a cos ) x sin + y cos – a sin cos = 0 ……..(2) The length of the perpendicular from the origin to the tangent (2) is – p = = a sin cos ……..(3) Hence from (1) & (3), = 3p Example 3 If & ' are the radii of curvature at the extremities of two conjugate diameters of the ellipse = 1 prove that Solution: Parametric equation of the ellipse is x = a cos , y=b sin = – a sin , = b cos = – a cos , = – b sin The radius of curvature at any point of the ellipse is given by = = – – – – – Page | 3 = ……(1) For the radius of curvature at the extremity of other conjugate diameter is obtained by replacing by + in (1). -

Curvatures of Smooth and Discrete Surfaces

Curvatures of Smooth and Discrete Surfaces John M. Sullivan Abstract. We discuss notions of Gauss curvature and mean curvature for polyhedral surfaces. The discretizations are guided by the principle of preserving integral relations for curvatures, like the Gauss/Bonnet theorem and the mean-curvature force balance equation. Keywords. Discrete Gauss curvature, discrete mean curvature, integral curvature rela- tions. The curvatures of a smooth surface are local measures of its shape. Here we con- sider analogous quantities for discrete surfaces, meaning triangulated polyhedral surfaces. Often the most useful analogs are those which preserve integral relations for curvature, like the Gauss/Bonnet theorem or the force balance equation for mean curvature. For sim- plicity, we usually restrict our attention to surfaces in euclidean three-space E3, although some of the results generalize to other ambient manifolds of arbitrary dimension. This article is intended as background for some of the related contributions to this volume. Much of the material here is not new; some is even quite old. Although some references are given, no attempt has been made to give a comprehensive bibliography or a full picture of the historical development of the ideas. 1. Smooth curves, framings and integral curvature relations A companion article [Sul08] in this volume investigates curves of finite total curvature. This class includes both smooth and polygonal curves, and allows a unified treatment of curvature. Here we briefly review the theory of smooth curves from the point of view we arXiv:0710.4497v1 [math.DG] 24 Oct 2007 will later adopt for surfaces. The curvatures of a smooth curve γ (which we usually assume is parametrized by its arclength s) are the local properties of its shape, invariant under euclidean motions. -

Discrete and Smooth Curves Differential Geometry for Computer Science (Spring 2013), Stanford University Due Monday, April 15, in Class

Homework 1: Discrete and Smooth Curves Differential Geometry for Computer Science (Spring 2013), Stanford University Due Monday, April 15, in class This is the first homework assignment for CS 468. We will have assignments approximately every two weeks. Check the course website for assignment materials and the late policy. Although you may discuss problems with your peers in CS 468, your homework is expected to be your own work. Problem 1 (20 points). Consider the parametrized curve g(s) := a cos(s/L), a sin(s/L), bs/L for s 2 R, where the numbers a, b, L 2 R satisfy a2 + b2 = L2. (a) Show that the parameter s is the arc-length and find an expression for the length of g for s 2 [0, L]. (b) Determine the geodesic curvature vector, geodesic curvature, torsion, normal, and binormal of g. (c) Determine the osculating plane of g. (d) Show that the lines containing the normal N(s) and passing through g(s) meet the z-axis under a constant angle equal to p/2. (e) Show that the tangent lines to g make a constant angle with the z-axis. Problem 2 (10 points). Let g : I ! R3 be a curve parametrized by arc length. Show that the torsion of g is given by ... hg˙ (s) × g¨(s), g(s)i ( ) = − t s 2 jkg(s)j where × is the vector cross product. Problem 3 (20 points). Let g : I ! R3 be a curve and let g˜ : I ! R3 be the reparametrization of g defined by g˜ := g ◦ f where f : I ! I is a diffeomorphism. -

Superellipse (Lamé Curve)

6 Superellipse (Lamé curve) 6.1 Equations of a superellipse A superellipse (horizontally long) is expressed as follows. Implicit Equation x n y n + = 10<b a , n > 0 (1.1) a b Explicit Equation 1 n x n y = b 1 - 0<b a , n > 0 (1.1') a When a =3, b=2 , the superellipses for n = 9.9 , 2, 1 and 2/3 are drawn as follows. Fig1 These are called an ellipse when n= 2, are called a diamond when n = 1, and are called an asteroid when n = 2/3. These are known well. parametric representation of an ellipse In order to ask for the area and the arc length of a super-ellipse, it is necessary to calculus the equations. However, it is difficult for (1.1) and (1.1'). Then, in order to make these easy, parametric representation of (1.1) is often used. As far as the 1st quadrant, (1.1) is as follows . xn yn 0xa + = 1 a n b n 0yb Let us compare this with the following trigonometric equation. sin 2 + cos 2 = 1 Then, we obtain xn yn = sin 2 , = cos 2 a n b n i.e. - 1 - 2 2 x = a sin n ,y = bcos n The variable and the domain are changed as follows. x: 0a : 0/2 By this representation, the area and the arc length of a superellipse can be calculated clockwise from the y-axis. cf. If we represent this as usual as follows, 2 2 x = a cos n ,y = bsin n the area and the arc length of a superellipse can be calculated counterclockwise from the x-axis. -

Arc Length and Curvature

Arc Length and Curvature For a ‘smooth’ parametric curve: xftygt= (), ==() and zht() for atb≤≤ OR for a ‘smooth’ vector function: rijk()tftgtht= ()++ () () for atb≤≤ the arc length of the curve for the t values atb≤ ≤ is defined as the integral b 222 ('())('())('())f tgthtdt++ ∫ a b For vector functions, the integrand can be simplified this way: r'(tdt ) ∫a Ex) Find the arc length along the curve rjk()tt= (cos())33+ (sin()) t for 0/2≤ t ≤π . Unit Tangent and Unit Normal Vectors r'(t ) Unit Tangent Vector Æ T()t = r'(t ) T'(t ) Unit Normal Vector Æ N()t = (can be a lengthy calculation) T'(t ) The unit normal vector is designed to be perpendicular to the unit tangent vector AND it points ‘into the turn’ along a vector curve’s path. 2 Ex) For the vector function rij()tt=++− (2 3) (5 t ), find T()t and N()t . (this blank page was NOT a mistake ... we’ll need it) Ex) Graph the vector function rij()tt= (2++− 3) (5 t2 ) and its unit tangent and unit normal vectors at t = 1. Curvature Curvature, denoted by the Greek letter ‘ κ ’ (kappa) measures the rate at which the ‘tilt’ of the unit tangent vector is changing with respect to the arc length. The derivation of the curvature formula is a rather lengthy one, so I will leave it out. Curvature for a vector function r()t rr'(tt )× ''( ) Æ κ= r'(t ) 3 Curvature for a scalar function yfx= () fx''( ) Æ κ= (This numerator represents absolute value, not vector magnitude.) (1+ (fx '( ))23/2 ) YOU WILL BE GIVEN THESE FORMULAS ON THE TEST!! NO NEED TO MEMORIZE!! One visualization of curvature comes from using osculating circles.