'The Dragon Run', a Travel Memoir of Bhutan with Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts

BORDERS AND CROSSINGS TRAVEL WRITING CONFERENCE Pula – Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS BORDERS AND CROSSINGS 2018 International and Multidisciplinary Conference on Travel Writing Pula-Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Published by Juraj Dobrila University of Pula For the Publisher Full Professor Alfio Barbieri, Ph.D. Editor Assistant Professor Nataša Urošević, Ph.D. Proofreading Krešimir Vunić, prof. Graphic Layout Tajana Baršnik Peloza, prof. Cover illustrations Joseph Mallord William Turner, Antiquities of Pola, 1818, in: Thomas Allason, Picturesque Views of the Antiquities of Pola in Istria, London, 1819 Hugo Charlemont, Reconstruction of the Roman Villa in the Bay of Verige, 1924, National Park Brijuni ISBN 978-953-7320-88-1 CONTENTS PREFACE – WELCOME MESSAGE 4 CALL FOR PAPERS 5 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 6 ABSTRACTS 22 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS 88 GENERAL INFORMATION 100 NP BRIJUNI MAP 101 Dear colleagues, On behalf of the Organizing Committee, we are delighted to welcome all the conference participants and our guests from the partner institutions to Pula and the Brijuni Islands for the Borders and Crossings Travel Writing Conference, which isscheduled from 13th till 16th September 2018 in the Brijuni National Park. This year's conference will be a special occasion to celebrate the 20thanniversary of the ‘Borders and Crossings’ conference, which is the regular meeting of all scholars interested in the issues of travel, travel writing and tourism in a unique historic environment of Pula and the Brijuni Islands. The previous conferences were held in Derry (1998), Brest (2000), Versailles (2002), Ankara (2003), Birmingham (2004), Palermo (2006), Nuoro, Sardinia (2007), Melbourne (2008), Birmingham (2012), Liverpool (2013), Veliko Tarnovo (2014), Belfast (2015), Kielce (2016) and Aberystwyth (2017). -

Bhutan Glacier Inventory 2018

BHUTAN GLACIER INVENTORY 2018 NATIONAL CENTER FOR HYDROLOGY AND METEOROLOGY NATIONAL CENTER FOR HYDROLOGY AND METEOROLOGY ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN www.nchm.gov.bt 2019 ISBN: 978-99980-862-2-7 BHUTAN GLACIER INVENTORY 2018 NATIONAL CENTER FOR HYDROLOGY & METEOROLOGY ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN 2019 Prepared by: Cryosphere Services Division, NCHM Published by: National Center for Hydrology and Meteorology Royal Government of Bhutan PO Box: 2017 Thimphu, Bhutan ISBN#:978-99980-862-2-7 © National Center for Hydrology and Meteorology Printed @ United Printing Press, Thimphu Foreword Bhutan is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Bhutan is already facing the impacts of climate change such as extreme weather and changing rainfall patterns. The Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB) recognizes the devastating impacts climate change can cause to the country’s natural resources, livelihood of the people and the economy. Bhutan is committed to addressing these challenges in the 12th Five Year Plan (2018-2023) through various commitments, mitigation and adaption plans and actions on climate change at the international, national, regional levels. Bhutan has also pledged to stay permanently carbon neutral at the Conference of Parties (COP) Summit on climate change in Copenhagen. Accurate, reliable and timely hydro-meteorological information underpins the understanding of weather and climate change. The National Center for Hydrology and Meteorology (NCHM) is the national focal agency responsible for studying, understanding and generating information and providing services on weather, climate, water, water resources and the cryosphere. The service provision of early warning information is one of the core mandates of NCHM that helps the nation to protect lives and properties from the impacts of climate change. -

Third Five Year Plan Introduction, Planning Commission

Forward The process of planned economic development in Bhutan started more than a decade ago. With the decade ending March, 1071, we have implemented two Five Plans. We are now in the midst of our Third Five Year Plan which was launched in April, 1972. This is the first time that we have printed our Plan document. With Our membership of the United Nations there has been an all-round increase of interest in Bhutan and it is, therefore, only appropriate that interested people should be able to know of our efforts to modernise our country and bring a measure of prosperity to our people. We are following a system of Annual Plans which enables us to review the progress of various schemes and shift the priorities where necessary. In this context, it would not be much relevant to include year- wise phasing of various programmes and we have, therefore, in this document confined our selves only to the Plan outlay as a whole. I take this opportunity to warmly thank the Government of India for their generous assistance not only in terms of money but also in providing technical personnel. While we are making determined efforts to plan our manpower requirements and orient the same to our development needs, it will be sometime before these efforts will bear fruit. CHAPTER I Introduction 1.1 The Kingdom of Bhutan, known as the 'Dragon Land' is situated in the heart of the Himalayas and has an area of about 18,000 sq. miles, roughly between 26.5 and 28.5 degree latitude and between 88 and 92 degree longitude. -

Annual Information Bulletin

དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། ཞབས་ཏོག་辷ན་ཁག སྲིད་བྱུས་དང་འཆར་ག筲་སྡེ་ཚན། 䍲མ་坴ག 2 ANNUAL 0 INFORMATION 1 BULLETIN 8 དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། ཞབས་ཏོག་辷ན་ཁག སྲིད་བྱུས་དང་འཆར་ག筲་སྡེ་ཚན། 䍲མ་坴ག དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། ཞབས་ཏོག་辷ན་ཁག སྲིད་བྱུས་དང་འཆར་ག筲་སྡེ་ཚན། 䍲མ་坴ག 2 ANNUAL 0 INFORMATION 1 BULLETIN 8 དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། ཞབས་ཏོག་辷ན་ཁག སྲིད་བྱུས་དང་འཆར་ག筲་སྡེ་ཚན། 䍲མ་坴ག NATIONAL HIGHWAYNational AND GEWOG Highway CONNECTIVITY and NETWORK Gewog AS OF Connectivity MAY 2018 Road Network National Highway Gewog Connectivity Road Border Road Gasa (23) Damji Dungkhar (23) Tashithang (37) (11) Toewang Rimchu Khoma (6) Bumdeling Naro (13) Gangzur Lhuentse Chhubu (1) (5) Samadingkha Bumthang (8.5) (29) (12) (12) (3) (28) Tang T/Yangtse Jangchubcholing Shengana (14) Tangmachu Zam Kabjisa Tangmachu Dodena Punakha (12) (16) (4) Kurjey (8) (9) (3) (17) Khuruthang Tashidingkha (7) Minjay Kawang Nobgang (15) (3) Nubi Pangrizampa Talo (4) (12) Lingmukha (14) Nobding Pelela Jakar Metsho (30) (7) (28) (16) (10) (9) Dungmethang (9) (17) (13) (49) Tshenkharla Dochula Samtengang (24) Yotongla Thimphu (16) (34) Drukgyal Dzong (39) Mesina(10) Toetsho Lawala Trongsa (6) Doteng (20) (28) Bajo Chuzomsa (21) (8) (6) (6.5) (10) Sheytangla (2) Nangar (36) (16) Chuserbu (27) Chhume Khamdang Wangdue (20) Ura (3) (14) Tshangkha Yalang (3) Jaray Tomzhangtshen Damthang Lamgong Dopshari Hesothangkha (16) (6) Gangte Kungarabten (12) (21) (7) (11) Autsho (8) Gasetshogom (4) Paro (35) (16) Gaselo Phobjikha (20) Duksum Ramjar (4) (31) Galakpa Bji Katsho (11) Thrumshingla (7.4) Bidung (7) Refee (10) (26) (14) -

Monday Morning on the Plane to Paro; Oct 22

Monday Morning on the plane to Paro; Oct 22 Last night we flew into Bangkok, arriving at 5:30 (with a one hour time change from HK, so now we were only 12 hours different than home). We made our way through customs and immigration (remembering the last time we did this we had to wait for Phyllis to prove she did not have Yellow Fever). We stepped outside to catch the shuttle to the airport hotel and were hit with a wall of heat. My glasses fogged up. I had forgotten the heat/humidity of Thailand. We spent the night at the Novotel, a large (really large) airport hotel, where Andy and I had stayed once before. The lobby is beautiful in the Thai style, with trees and sculptures of lotus flowers. We went to our room, and by 8:00 were fast asleep. Good thing as we had to get up at 3:00 (AM!!) to catch our morning flight to Bhutan. We had our breakfast buffet (which opens at 3:30 – lots of travelers here with early morning flights) and shuttled back to the airport to check in with Druk Air, the Royal Bhutan Airline. (Druk in Bhutanese means Thunder Dragon). There were surprising a lot of people there for 4:30 in the morning. We checked in and asked for a window seat as Alvin told us the view flying into Paro was amazing. I asked the agent specifically not to be sitting on the wing. We were driven by bus to the plane. And guess where we ended up sitting? On the wing. -

The Judiciary of the Kingdom of Bhutan

The Judiciary of the Kingdom of Bhutan THE JUDICIARY OF THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN HISTORICAL BACKGROUND - The Bhutanese legal system has a long traditional background, primarily based on Buddhist natural law and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal’s Code from early 17th century. The first comprehensive codified laws known as the Thrimzhung Chhenmo or the Supreme Law was enacted by the National Assembly during the Third Druk Gyalpo, His Majesty Jigme Dorji Wangchuck’s reign. MISSION, POLICIES & OBJECTIVES - The Judiciary aims to safeguard, uphold, and administer Justice fairly and independently without fear, favour, or undue delay in accordance with the Rule of Law to inspire trust and confidence and to enhance access to Justice. INDEPENDENCE - Among others, the independence of the Judiciary is manifested through: (a) Separation of judicial power from the apex to the lowest court; (b) Collective independence (the concept of non-interference, jurisdictional monopoly, transfer jurisdiction, control over judicial administration); (c) Institutional and financial independence; (d) Personnel independence (qualification, selection and training, conditions of services, suspension, removal and disciplinary measures. Security of tenure and protection from arbitrary removal from office); (e) Decentralization of all personnel administration and financial operations to respective courts; and (f) Distinctive court building, distinct kabney and court seal. JURISDICTION The Royal Court of Justice The judicial authority of Bhutan is vested in the Royal Courts of Justice comprising the Supreme Court, the High Court, the Dzongkhag Court and the Dungkhag Court. Other courts and tribunals will be established from time to time by the Druk Gyalpo on the recommendation of the National Judicial Commission. Additional Benches are established in some Dzongkhags and Dungkhags with higher caseload. -

Edwards H. Metcalf Library Collection on TE Lawrence

Edwards H. Metcalf Library Collection on T.E. Lawrence: Scrapbooks Huntington Library Scrapbook 1 Page Contents 1 recto [Blank]. 1 verso Anal. 1. Newspaper clipping. North, John, 'Hejaz railway brings back memories of Lawrence', Northern Echo, June 14, 1965. Anal. 2. Newspaper clipping. 'Memories of T.E.', Yorkshire Post, May 18, 1965. Mss. Note from Beaumont 'Please accept these free with my compliments. T.W. Beaumont'. 2 recto Black-and-white photograph of Beaumont. 'Thomas W. Beaumont Served under T.E. Lawrence in Arabia as his Sgt. Vickers Gunner'. 2 verso Black-and-white photograph. Mss. 'To my friend Theodora Duncan with every good wish. T.W. Beaumont' Typed note. ' Parents of Peter O'Toole with T.W. Beaumont At the gala opening of the film "Lawrence of Arabia", at the Majestic Theatre in Leeds, Yorkshire, Sunday evening, Oct. 13, 1963'. 3 recto Anal. 3. Newspaper clipping. 'A Lawrence Talks About That Legend', Leeds, Yorkshire, April 10, 1964. Two black-and-white photographs. 'Mr. T. W. Beaumont meets Dr. M.R. Lawrence elder brother of T.E. Lawrence, at Leeds City Station, Yorkshire. April 10, 1964. 3 verso Newspaper cartoon. 'Boy! I'm glad they don't use US nowadays!' Anal. 4. 'The following small photographs were taken during WW-I on the Eastern Front by T.W. Beaumont & friends, and smuggled out of Arabia. Newspaper cartoon. 'Arms for the love of Allah!' 4 recto Black-and-white photograph. 'Siwa Oasis, 1915-17 Involved in the defense of Suez. Operations against the Senussi in Lybian Desert. Photographed by C.S. -

Entomological Fieldwork Bhutan May-June 2017

Mission Report Entomological fieldwork Bhutan May-June 2017 Jan van Tol for C. Gielis, F.K. Gielis, W.F. Klein, J. van Tol & O. Vorst (the Netherlands), and Ch. Dorji, P. Dorji, T. Gyeltshen, T. Nidup & K. Wangdi (Bhutan) December 2017 Team Klein in Phuentshogthang From left to right: (standing) Thinley Gyeltshen, Phurpa Dorji, Cheten Dorji, Wim Klein, Oscar Vorst, Tshering Nidup; (sitting) Jan van Tol and Kuenzang Choeda. Internal report of Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, The Netherlands December 2017 |2 Mission Report Entomological fieldwork Bhutan May-June 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 1. Introduction .................................1 Three years ago, the National Biodiversity Centre 2. Participants and contacts ......................2 (Bhutan) and Naturalis Biodiversity Center signed 3. Itinerary, meetings ...........................3 a Memorandum of Understanding for scientific 4. Sampling stations ............................5 cooperation. An important partner for the scientific 5. Costs estimate, visa etc .......................17 and outreach activities was the Bhutan Trust Fund 6. Observations and suggestions for future for Environmental Conservation (Thimphu), which fieldwork ...................................19 provided a grant of USD 150,000 for the period 2014-2016. Although the grant ended by the end of Appendices 2016, but it was decided that further entomological fieldwork was needed, for instance to prepare for the 1. Photographs of localities aquatic insects .......21 next phase which will focus on applied entomology 2. Maps .......................................35 and water quality assessment. Costs of the Bhutanese 3. Permits .....................................41 counterparts for this fieldwork were covered by a grant 4. Memorandum of Understanding ..............49 of Naturalis. 5. Research proposal 2017 .......................55 We would like to thank for support our colleagues in Naturalis (Prof. -

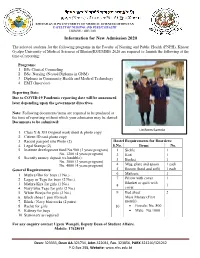

Information for New Admission 2020

KHESAR GYALPO UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES OF BHUTAN FACULTY OF NURSING AND PUBLIC HEALTH THIMPHU: BHUTAN Information for New Admission 2020 The selected students for the following programs in the Faculty of Nursing and Public Health (FNPH), Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan(KGUMSB) 2020 are required to furnish the following at the time of reporting: Programs: 1. BSc.Clinical Counseling 2. BSc. Nursing (Nested Diploma in GNM) 3. Diploma in Community Health and Medical Technology 4. EMT (Inservice) Reporting Date: Due to COVID-19 Pandemic reporting date will be announced later depending upon the government directives. Note: Following documents/items are required to be produced at the time of reporting without which your admission may be denied: Documents to be submitted: Uniform Sample 1. Class X & XII Original mark sheet & photo copy 2. Citizen ID card photo copy 3. Recent passport size Photo (2) Hostel Requirements for Boarders: 4. Legal Stamps (2) S.No. Items No. 5. Institute development fund Nu.900 (3 years program) 1 Sickle 1 Nu. 1200 (4 years program) 2 Koti 1 6. Security money deposit (refundable): 3 Bucket 1 Nu. 3000 (3 years program) Nu. 4000 (4 years program) 4 Mug, plate and spoon 1 each 5 Broom (hard and soft) 1 each General Requirements: 1. Mathra Gho for boys (1 No.) 6 Mattress 1 2. Lagay or Tego for boys (2 Nos.) 7 Pillow with cover 1 Blanket or quilt with 3. Mathra Kira for girls (1 No.) 8 1 4. Navy blue Tego for girls (2 No.) cover 5. White Wonju for girls (2 No.) 9 Bed sheet 2 6. -

Your Gateway to Bhutan for a Unique Experience with Your Loved Ones

JULY-AUGUST/2013 01 COVER STORY 10 THE NEW facE OF BHUtan’s DEMOcracy 22 Article PHOTO ESSAY 48 Know Your Food Generation In-be tween Seshy Shamu Pith Instructions For Understanding Bhutan’s Youth. 50 Restaurant 14 IMAGES FROM BEFORE AND Review DURING THE GENERAL ELEctION 32 Feature Jimmy’s Kitchen Quality Education How can Bhutan 52 Movie Review achieve it. Arrows or the Thunder LIVING WITH Dragon. 26 Travel London Calling 54 Book Review The White Tiger. 60 LIVING WITH SEWING MACHINES 40 Feature 60 Leisure Emprowering Rural Communities, Creating 66 Most Discussed Conditions for rural INTERVIEW prosperity. 68 Art Page 54 THIRD EYE 30 Column 72 Last Word Election Aftermath: Zero Point Eight Meters A milestone or a millstone ? 44 What’s New? Trends The Raven July / August, 2013 1 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Sir/Madam, There are lessons to be learnt from The Raven on Greetings from Munich, Germany. what journalism is about; reporting things as seen I am regularly in Bhutan, guiding pilgrimage or heard without taking sides. groups. I heard about The Raven magazine and This and its analytical treatment of the real con- I am very interested in reading it. temporary issues is probably why The Raven has Also, do you have a website, foreign subscrip- established and maintained a serious readership. tions? Tshewang Tashi, Thimphu Detlev Gobel, Germany My name is Ford Hamidi and I am from Canada. I spent some time working in Bhutan and became The monastic community can be above poli- fond of your magazine with it’s high quality arti- tics, but not above the law especially when it cles and design. -

Eric Newby Worked Briefly in Advertising Before Joininga Finnish Four-Masted Bark in 1938, an Experience He Described in the Last Grain Race

PENGUIN BOOKS A SHORT WALK IN THE HINDU RUSH Born in London in 1919 and educated at St. Paul's School, Eric Newby worked briefly in advertising before joininga Finnish four-masted bark in 1938, an experience he described in The Last Grain Race. In 1942 he was captured off Sicily while trying to rejoin the submarine from which he had landed to attack a German airfield. When the Snow Comes, They Will Take You Away describes how he escaped with the aid of the woman he subsequently married. For nine years or so he worked in the wholesale fashion business, "tottering up the back stairs of stores with armfuls of stock" (of which he wrote in Something Wholesale), and in a Mayfair couture house. Then he left to explore wildest Nuristan, an expedition hilariously chronicled in A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. In 1963—after some years as fashion buyer to a chai n of department stores-—together with his wife, Wanda, he made a 1,200-mile descent of the Ganges, described in Slowly down the Ganges. On his return he became travel editor of the Observer. Other books by Eric Newby include Love and War in the Apennines, The World Atlas of Exploration, and Great Ascents. His most recent book, The Big Red Train Ride, an account of his journey from Moscow to the Pacific on the Trans-Siberian Railway, is also published by Penguin Books. He and his wife now live in Devonshire when not traveling abroad. ERIC NEWBY A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush Preface by Evelyn Waugh PENGUIN BOOKS Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books, 625 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10022, U.S.A. -

Chapter 5 Spatial Pattern and Environmental Conditions of Bhutan

The Project for Formulation of Comprehensive Development Plan for Bhutan 2030 Final Report CHAPTER 5 SPATIAL PATTERN AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS OF BHUTAN 5.1 Existing Land Cover 5.1.1 Land Cover in 2010 Collected existing land cover data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MoAF) was generated by a supervised classification method using satellite images from ALOS AVNIR-2, acquired between 2006 and 2009. The collected land cover data can be broken down into 11 main classes and 15 sub-classes. A list and map of the land cover classes are shown below. Table 5.1.1 List of Land Cover Classes (1) Class Sub-Class Category Symbol Area (ha) % Forests Conifer Forest Fir Forest FCf 183,944 4.74 Mixed Conifer Forest FCm 614,545 15.85 Blue Pine Forest FCb 77,398 2.00 Chir Pine Forest FCc 107,353 2.77 Broadleaf Forest Broadleaf Forest FB 1,688,832 43.56 Broadleaf and Conifer Forest FBc 31,463 0.81 Shrubs - - SH 419,128 10.81 Meadows - - GP 157,238 4.06 Cultivated Chhuzhing Land - AC 31,127 0.80 Agricultural Land Kamzhing Land - AK 69,487 1.79 Horticultural Apple Orchard HA 2,039 0.05 Land Citrus Orchard HC 5,086 0.13 Areca Nut Plantation HAa 984 0.03 Cardamom Plantation HCo 3,398 0.09 Others HO 17 0.00 Built-Up Area - - BA 6,194 0.16 Non-Built Up Area - - NB 330 0.01 Snow Cover - - OS 299,339 7.72 Bare Areas Rocky Outcrops - RR 107,539 2.77 Scree - RS 23,263 0.60 Bare Soils - BS 27 0.00 Water Bodies Lakes - WL 4,751 0.12 Reservoirs - WRe 131 0.00 Rivers - WR 22,563 0.58 Marshy Areas - - MA 319 0.01 Degraded Areas Landslides - DL 6,999 0.18