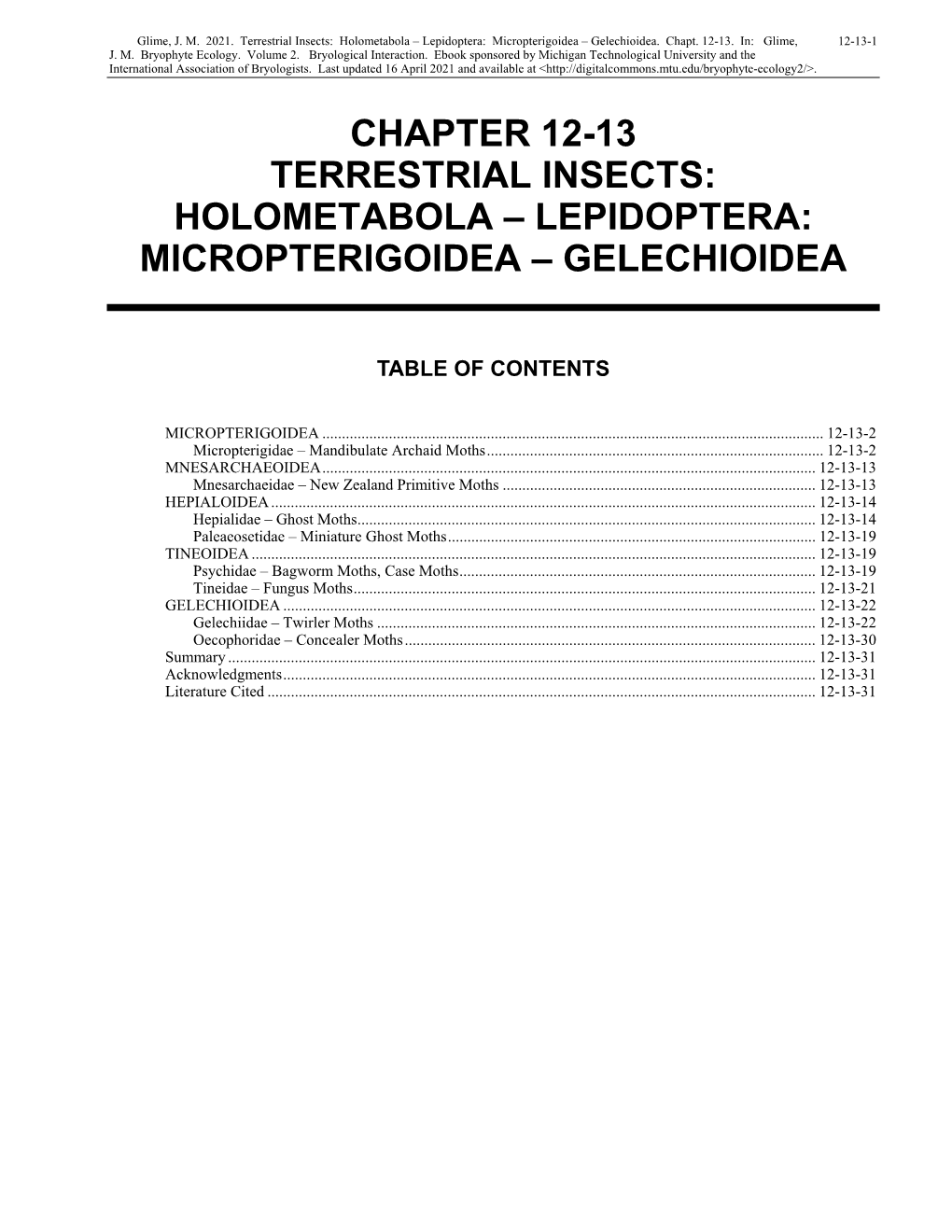

Volume 2, Chapter 12-13: Terrestrial Insects: Holometabola–Lepidoptera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22 3 205 210 Strakh Yefrem.P65

Russian Entomol. J. 22(3): 205210 © RUSSIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL JOURNAL, 2013 New records of Elasmus Westwood, 1833 (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) species from Southeast Asia Íîâûå íàõîäêè âèäîâ ðîäà Elasmus Westwood, 1833 (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) èç Þãî-âîñòî÷íîé Àçèè I.S. Strakhova1, Z.A. Yefremova1, 2 È.Ñ. Ñòðàõîâà1, Ç.À. Åôðåìîâà1, 2 1 Ulyanovsk State Pedagogical University, 4 pl. 100-letya, Ulyanovsk 432700, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Óëüÿíîâñêèé ãîñóäàðñòâåííûé ïåäàãîãè÷åñêèé óíèâåðñèòåò, ïë. 100-ëåòèÿ, 4, Óëüÿíîâñê 432700, Ðîññèÿ. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Zoology, George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Israel. Êàôåäðà çîîëîãèè, ôàêóëüòåò íàóê î æèçíè èìåíè Æîðæà Âàéçà, Òåëü-Àâèâñêèé óíèâåðñòèòåò, Èçðàèëü. KEY WORDS: Elasmus, Eulophidae, Hymenoptera, Southeast Asia. ÊËÞ×ÅÂÛÅ ÑËÎÂÀ: Elasmus, Eulophidae, Hymenoptera, Þãî-Âîñòî÷íàÿ Àçèÿ. ABSTRACT: Nine species of the genus Elasmus the present study, Elasmus species were not reported are newly recorded from continental Southeast Asia from Thailand. Elasmus brevicornis and E. johnstoni with diagnoses, distributions and remarks. E. philippi- Ferrière, 1929 are known from Myanmar (Burma) [Hert- nensis Ashmead, 1904 is re-described. A key to species ing, 1975, 1977]. Elasmus species were not found in of the genus Elasmus known from Thailand is presented. Cambodia and Laos. Seven species (Elasmus anticles Walker, 1846, E. brevicornis, E. cameroni Verma et ÐÅÇÞÌÅ: Äåâÿòü âèäîâ ðîäà Elasmus âïåðâûå Hayat, 1986, E. corbetti Ferrière, 1930, E. hyblaeae óêàçûâàþòñÿ äëÿ êîíòèíåíòàëüíîé ÷àñòè Þãî-Âîñ- Ferrière, 1929, E. nephantidis, E. philippinensis Ash- òî÷íîé Àçèè ñ äèàãíîçîì, ðàñïðîñòðàíåíèåì è êîì- mead, 1904) are known from Malaysia [Ferrière, 1930; ìåíòàðèÿìè. -

List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) A list of the UK BAP priority terrestrial invertebrate species, divided by taxonomic group into: Insects, Arachnids, Molluscs and Other invertebrates (Crustaceans, Worms, Cnidaria, Bryozoans, Millipedes, Centipedes), is provided in the tables below. The list was created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report published in 2007. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Insects Scientific name Common Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK name Ireland BAP species? Acosmetia caliginosa Reddish Buff moth Y N Yes – SAP Acronicta psi Grey Dagger moth Y Y Y Y Acronicta rumicis Knot Grass moth Y Y N Y Adscita statices The Forester moth Y Y Y Y Aeshna isosceles -

English Nature Research Report No

23 6 REQUIREMENTS FOR CONSERVATION 6.1 Introduction A very few examples of the artificial habitats considered in this report have statutory protection as SSSI or LNRs, A few, not all the same ones, have good invertebrate records. None have good enough invertebrate records, as seen in the Introduction, to be able to define invertebrate "communities" by more than species lists and, cxcasionally, relative abundances of some species in a very few years. The importance of such habitats for biodiversity consewation is however substantial, as demonstrated above. Few Broad Habitat types could boast as inany as 12-15% of the list of nationally scarce and rare species, and no other for which no Key Habitat has been defined. The situation is therefore one in which we have the minimal knowledge needed to know how important the problem is and, so far, only the skeleton of a conservation strategy which will address it, Clearly we need to know more about the invertebrates, more about the sites concerned and have a better strategy for conservation. It is not easy to judge how to do this and to set the priorities in the right urder. In the following I leave aside the purely synanthropic species which are either controversial for conservation (such as specific parasites) or common species present as curiosities well outside their global range (such as camel crickets and the range of tropical pyralid moths which breed in aquatic nurseries). 6.2 lnvertcbratc surveys We know too little about the invertebrate faunas of artificial sites, in particular and in general, There are two consequences of this, First, important sites may disappear unknown because they have not been surveyed or have been inadequately surveyed. -

Groundnut Leaf Miner

Contributions to the body of knowledge of groundnut fructification, calcium nutrition and its major pest, the groundnut leaf miner The Professorial Inaugural lecture by Prof Godfrey E. Zharare Aim of Lecture 1) To highlight my contributions to the body of knowledge on . Fructification and calcium nutrition. Groundnut leaf miner pest. 2) To highlight areas for further research. Presentation outline 1. Introduction-Groundnut leaf miner and fructification/pops problems 2. Development of solution culture techniques for detailed studies on groundnut pops problem 3. Findings from studies on groundnut fructification and calcium nutrition 4. Research focus area for solving the groundnut pops problem 5. Research findings on the groundnut leaf miner 6. Research focus areas Identified for the groundnut leaf miner Introduction Rational for the research Groundnut is a food, oil and cash crop Productivity of the crop is seriously reduced by production of empty pods (pops). Very limited information on the new devastating groundnut leaf miner pest. Introduction-Crop Damage by Groundnut Leaf Miner • (A) and (B) early season leaf symptoms • (C) late season symptoms • (D) Complete crop defoliation • (E) the destructive groundnut leaf miner larva • (F) The adult groundnut leaf miner moth Introduction- The Empty Pods (Pops) Problem of groundnut • Pops are a result of reproductive nature of groundnut • Caused by calcium deficiency due to lack of xylem transport to pods. • Soluble calcium source (gypsum) needs to applied at pegging to avoid pops Groundnut plants showing gynophore • Response is inconsistent penetrating the soil • The aetiology of the disease and The morphology of the role of calcium were unknown groundnut plant. -

New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2018 Band/Volume: 0039 Autor(en)/Author(s): Grehan John R., Witt Thomas Josef, Ignatyev Nikolay N. Artikel/Article: New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae) and a 5,000 km biogeographic disjunction 849-862 Entomofauna 39/239/1 HeftHeft 19:##: 849-862000-000 Ansfelden, 31.2. Januar August 2018 2018 New Species of Aenetus from Sumatra, Indonesia (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae) and a 5,000 km biogeographic disjunction John R. GREHAN, THOMAS J. WITT & NIKOLAI IGNATEV Abstract Discovery of Aenetus sumatraensis nov.sp. from northern Sumatra expands the distribution range of this genus well into southeastern Asia along the Greater and Lesser Sunda. The species belongs to the A. tegulatus clade distributed between northern Australia, New Gui- nea, islands west of New Guinea and the Lesser Sunda that are separated by over 5,000 km from A. sumatraensis nov.sp.. The Sumatran record either represents local differentiation from a formerly widespread ancestor or it is part a larger distribution of the A. tegulatus clade in the Greater Sunda that has not yet been discovered. The bursa copulatrix of the Australian species referred to as A. tegulatus is different from specimens examined in New Guinea and Ambon Islands (locality for the type) and is therefore referred to here as A. ther- mistes stat.rev. Zusammenfassung Die Entdeckung von Aenetus sumatraensis nov.sp. in Nord-Sumatra dehnt das Verbreitungs- gebiet dieser Gattung aus bis nach Südostasien entlang der Großen und Kleinen Sundainseln. -

Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung / C / 42 (1987)

1352 Notes (Z)-3-TetradecenyI Acetate as a Sex-Attractant species feed on Picea, Rumex and Rubus, respective Component in Gelechiinae and Anomologinae ly, and their relative trap captures greatly varied (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) between test sites, depending on host abundance; Ernst Priesner which may explain why one species (A. micella) was missing from the test by Willemse et al. Max-Planek-Institut für Verhaltensphysiologie. D-8131 Seewiesen The outstanding effectiveness of the Z3-14:Ac for Z. Naturforsch. 42c, 1352—1355 (1987); males of these gelechiid species was supported by received August 25, 1987 electroantennogram measurements. These were Sex-Attractant, Attraction-Inhibitor, J3-Alkenyl made from males newly taken in Z3-14:Ac baited A cetates, Chionodes, Monochroa, Argolamprotes, traps (with antennae not yet glued to the adhesive), Aproaerema, Gelechiidae using technical procedures as in other Microlepido- The title compound, unreported as an insect pheromone ptera [3, 4], In the series of (Z)- and (£)-alkenyl ace component, effectively attracted certain male Gelechiidae tates, varied for chain length and double bond posi (genera Chionodes, Monochroa, Argolamprotes) as a sin gle chemical. Trap captures with this chemical decreased tion, the Z3-14:Ac, at the test amount of 1 |ig, elic on addition of either (E)-3-dodecenyl acetate, (£)-3-tetra- ited the greatest EAG response. This was followed decenyl acetate or (Z)-3-tetradecen-l-ol, the sexual attrac- by the geometric isomer (.O-MiAc), the corre tants of other, closely related species. Results on an Aproaerem a test species showing a synergistic attraction sponding alcohol analogue (Z3-14:OH) and some response to combinations of (Z)-3-tetradecenyl acetate positional isomers and shorter-chain homologues with its homologue (Z)-3-dodecenyl acetate are included. -

Erster Nachtrag Zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns

©Entomologischer Verein Apollo e.V. Frankfurt am Main; download unter www.zobodat.at Nachr. entomol. Ver. Apollo, N.F. 17 (2): 209-224 (1996) 209 Erster Nachtrag zur Mikrolepidopterenfauna Zyperns Ernst Arenberger und Josef Wimmer Ernst A renberger, Börnergasse 3, 4/6, A-1190 Wien, Österreich Josef Wimmer, Feldstraße 3 D, A-4400 Steyr, Österreich Zusammenfassung: Vor allem durch die Aufsammlungen von J. Wimmer, Steyr, wird die Liste der von Zypern bekannten Mikrolepidopterenfauna um 35 Arten vermehrt und auf insgesamt 496 Taxa ergänzt. Schlüsselwörter: Insecta, Lepidoptera, Mikrolepidoptera, Systematik, Fauni- stik, palaearktische Region, Fauna Zyperns. First Supplement to the microlepidopteran fauna of Cyprus Abstract: The list of the species of microlepidoptera of Cyprus is increased from 461 species to 496 taxa now in total, especially by the collections of J. Wimmer, Steyr, Austria. Key words: Insecta, Lepidoptera, Microlepidoptera, systematics, faunistics, Palaearctic region, fauna of Cyprus. Einleitung Schon kurze Zeit nach Erscheinen der Zusammenfassung aller bisher ge meldeten Meldungen über die Mikrolepidopteren Zyperns (Arenberger 1995) liegen wieder zahlreiche noch unveröffentlichte Funde aus Zypern vor. Es handelt sich insbesondere um Aufsammlungen von J. Wimmer in den Jahren 1993-1995 in der Umgebung von Paphos. Die bisherigen Sam melergebnisse bezogen sich einerseits auf den Norden der Insel, der Um gebung von Kyrenia, und andererseits auf das gebirgige Zentrum im Troodos-Gebirge sowie das Küstengebiet des Südens (Karte siehe bei Arenberger 1995). Jetzt können auch Angaben über die Fauna des westli chen Teiles der Insel gemacht werden. Ergänzt wird der vorliegende Beitrag durch restliche Arten aus den Aus beuten K. Mikkolas und des Autors, die bei Arenberger (1995) nicht ein bezogen werden konnten, sowie einige Funde von R. -

Lampropteryx Otregiata (METCALFE, 1917) Und Aplota Palpella

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Melanargia - Nachrichten der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Rheinisch- Westfälischer Lepidopterologen e.V. Jahr/Year: 2012 Band/Volume: 24 Autor(en)/Author(s): Schumacher Heinz Artikel/Article: Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE, 1917) und Aplota palpella (HAWORTH, 1828) im Bergischen Land (NRW) (Lep., Geometridae et Oecophoridae) 1-5 Melanargia, 24 (1): 1-5 Leverkusen, 1.4.2012 Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE , 1917) und Aplota palpella (HAWORTH , 1828) im Bergischen Land (NRW) (Lep., Geometridae et Oecophoridae) von HEINZ SCHUMACHER Zusammenfassung: Beschrieben wird ein Wiederfund der in Nordrhein-Westfalen als verschollen eingestuften Spannerart Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE , 1917) sowie der Erstnachweis von Aplota palpella (HAWORTH , 1828) für das Bergische Land. Abstract: Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE , 1917) and Aplota palpella (HAWORTH , 1828) in the the Bergi- sches Land region (North-Rhine Westphalia) Refinding in North-Rhine Westphalia of the geometrid species Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE , 1917) which was considered to be lost as well as the first record of Aplota palpella (Haworth, 1828) for the Bergisches Land. 1986 fanden H.-J. WEIGT und A. BENNEWITZ den Sumpflabkraut-Blattspanner Lampropteryx otregiata (METCALFE , 1917 ) in einem Tal im Arnsberger Wald (Kreis Soest, nördliches Sauerland) (WEIGT 1986). Die Fundorte liegen in einer Höhe zwischen 250-300 m ü.NN (WEIGT schriftl.Mitt.). Es handelte sich damals um den Erstnachweis für Nordrhein-Westfalen. Da in der Folgezeit weitere Funde in NRW nicht bekannt geworden sind, wurde L. otregiata in der aktuel- len Roten Liste der in Nordrhein-Westfalen gefährdeten Schmetterlinge von 2010 als verschollen eingestuft (ROTE LISTE NRW 2010: Bearbeitungsstand Juli 2010). -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Amphiesmeno- Ptera: the Caddisflies and Lepidoptera

CY501-C13[548-606].qxd 2/16/05 12:17 AM Page 548 quark11 27B:CY501:Chapters:Chapter-13: 13Amphiesmeno-Amphiesmenoptera: The ptera:Caddisflies The and Lepidoptera With very few exceptions the life histories of the orders Tri- from Old English traveling cadice men, who pinned bits of choptera (caddisflies)Caddisflies and Lepidoptera (moths and butter- cloth to their and coats to advertise their fabrics. A few species flies) are extremely different; the former have aquatic larvae, actually have terrestrial larvae, but even these are relegated to and the latter nearly always have terrestrial, plant-feeding wet leaf litter, so many defining features of the order concern caterpillars. Nonetheless, the close relationship of these two larval adaptations for an almost wholly aquatic lifestyle (Wig- orders hasLepidoptera essentially never been disputed and is supported gins, 1977, 1996). For example, larvae are apneustic (without by strong morphological (Kristensen, 1975, 1991), molecular spiracles) and respire through a thin, permeable cuticle, (Wheeler et al., 2001; Whiting, 2002), and paleontological evi- some of which have filamentous abdominal gills that are sim- dence. Synapomorphies linking these two orders include het- ple or intricately branched (Figure 13.3). Antennae and the erogametic females; a pair of glands on sternite V (found in tentorium of larvae are reduced, though functional signifi- Trichoptera and in basal moths); dense, long setae on the cance of these features is unknown. Larvae do not have pro- wing membrane (which are modified into scales in Lepi- legs on most abdominal segments, save for a pair of anal pro- doptera); forewing with the anal veins looping up to form a legs that have sclerotized hooks for anchoring the larva in its double “Y” configuration; larva with a fused hypopharynx case. -

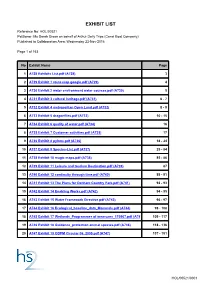

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

An Annotated List of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 38: 1–549 (2010) Annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 MONOGRAPH www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada Gregory R. Pohl1, Gary G. Anweiler2, B. Christian Schmidt3, Norbert G. Kondla4 1 Editor-in-chief, co-author of introduction, and author of micromoths portions. Natural Resources Canada, Northern Forestry Centre, 5320 - 122 St., Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6H 3S5 2 Co-author of macromoths portions. University of Alberta, E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum, Department of Biological Sciences, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E3 3 Co-author of introduction and macromoths portions. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, K.W. Neatby Bldg., 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0C6 4 Author of butterfl ies portions. 242-6220 – 17 Ave. SE, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2A 0W6 Corresponding authors: Gregory R. Pohl ([email protected]), Gary G. Anweiler ([email protected]), B. Christian Schmidt ([email protected]), Norbert G. Kondla ([email protected]) Academic editor: Donald Lafontaine | Received 11 January 2010 | Accepted 7 February 2010 | Published 5 March 2010 Citation: Pohl GR, Anweiler GG, Schmidt BC, Kondla NG (2010) An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada. ZooKeys 38: 1–549. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 Abstract Th is checklist documents the 2367 Lepidoptera species reported to occur in the province of Alberta, Can- ada, based on examination of the major public insect collections in Alberta and the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes.