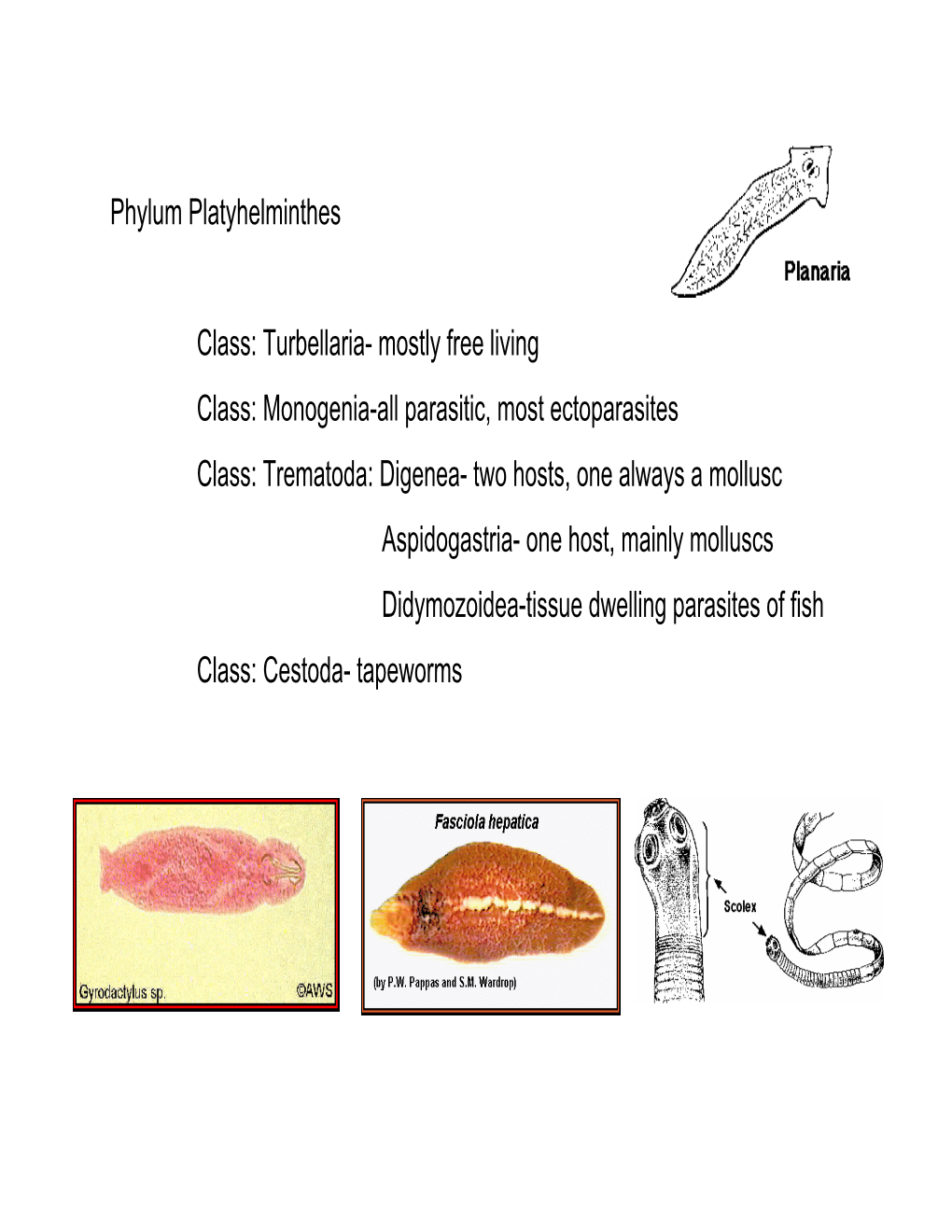

Phylum Platyhelminthes Class: Turbellaria- Mostly Free Living Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on the Systematics of the Cestodes Infecting the Emu

10F z ú 2 n { Studies on the systematics of the cestodes infecting the emu, Dromaíus novuehollandiue (Latham' 1790) l I I Michael O'Callaghan Department of Environmental Biology School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The llniversity of Adelaide Frontispiece. "Hammer shaped" rostellar hooks of Raillietina dromaius. Scale bars : l0 pm. a DEDICATION For mum and for all of the proficient scientists whose regard I value. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1-11 Declaration lll Acknowledgements lV-V Publication arising from this thesis (see Appendices H, I, J). Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Generalintroduction 1 1.2 Thehost, Dromaius novaehollandiae(Latham, 1790) 2 1.3 Cestodenomenclature J 1.3.1 Characteristics of the family Davaineidae 4 I.3.2 Raillietina Fuhrmann, 1909 5 1.3.3 Cotugnia Diamare, 1893 7 t.4 Cestodes of emus 8 1.5 Cestodes from other ratites 8 1.6 Records of cestodes from emus in Australia 10 Chapter 2. GENERAL MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1 Cestodes 11 2.2 Location of emu farms 11 2.3 Collection of wild emus 11 2.4 Location of abattoirs 12 2.5 Details of abattoir collections T2 2.6 Drawings and measurements t3 2.7 Effects of mounting medium 13 2.8 Terminology 13 2.9 Statistical analyeis 1.4 Chapter 3. TAXONOMY OF THE CESTODES INFECTING STRUTHIONIFORMES IN AUSTRALIA 3.1 Introduction 15 3.2 Material examined 3.2.1 Australian Helminth Collection t6 3.2.2 Parasitology Laboratory Collection, South Australian Research and Development Institute 17 3.2.3 Material collected at abattoirs from farmed emus t7 J.J Preparation of cestodes 3.3.1 -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Clinical Cysticercosis: Diagnosis and Treatment 11 2

WHO/FAO/OIE Guidelines for the surveillance, prevention and control of taeniosis/cysticercosis Editor: K.D. Murrell Associate Editors: P. Dorny A. Flisser S. Geerts N.C. Kyvsgaard D.P. McManus T.E. Nash Z.S. Pawlowski • Etiology • Taeniosis in humans • Cysticercosis in animals and humans • Biology and systematics • Epidemiology and geographical distribution • Diagnosis and treatment in humans • Detection in cattle and swine • Surveillance • Prevention • Control • Methods All OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) publications are protected by international copyright law. Extracts may be copied, reproduced, translated, adapted or published in journals, documents, books, electronic media and any other medium destined for the public, for information, educational or commercial purposes, provided prior written permission has been granted by the OIE. The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The views expressed in signed articles are solely the responsibility of the authors. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. –––––––––– The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the World Health Organization or the World Organisation for Animal Health concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

A Large 28S Rdna-Based Phylogeny Confirms the Limitations Of

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysA 500: large 25–59 28S (2015) rDNA-based phylogeny confirms the limitations of established morphological... 25 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.500.9360 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A large 28S rDNA-based phylogeny confirms the limitations of established morphological characters for classification of proteocephalidean tapeworms (Platyhelminthes, Cestoda) Alain de Chambrier1, Andrea Waeschenbach2, Makda Fisseha1, Tomáš Scholz3, Jean Mariaux1,4 1 Natural History Museum of Geneva, CP 6434, CH - 1211 Geneva 6, Switzerland 2 Natural History Museum, Life Sciences, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK 3 Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic 4 Department of Genetics and Evolution, University of Geneva, CH - 1205 Geneva, Switzerland Corresponding author: Jean Mariaux ([email protected]) Academic editor: B. Georgiev | Received 8 February 2015 | Accepted 23 March 2015 | Published 27 April 2015 http://zoobank.org/DC56D24D-23A1-478F-AED2-2EC77DD21E79 Citation: de Chambrier A, Waeschenbach A, Fisseha M, Scholz T and Mariaux J (2015) A large 28S rDNA-based phylogeny confirms the limitations of established morphological characters for classification of proteocephalidean tapeworms (Platyhelminthes, Cestoda). ZooKeys 500: 25–59. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.500.9360 Abstract Proteocephalidean tapeworms form a diverse group of parasites currently known from 315 valid species. Most of the diversity of adult proteocephalideans can be found in freshwater fishes (predominantly cat- fishes), a large proportion infects reptiles, but only a few infect amphibians, and a single species has been found to parasitize possums. Although they have a cosmopolitan distribution, a large proportion of taxa are exclusively found in South America. -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Invertebrates Invertebrates: • Are Animals Without Backbones • Represent 95% of the Animal Kingdom Animal Diversity Morphological Vs

Invertebrates Invertebrates: • Are animals without backbones • Represent 95% of the animal kingdom Animal Diversity Morphological vs. Molecular Character Phylogeny? A tree is a hypothesis supported or not supported by evidence. Groupings change as new evidence become available. Sponges - Porifera Natural Bath Sponges – over-collected, now uncommon Sponges • Perhaps oldest animal phylum (Ctenphora possibly older) • may represent several old phyla, some now extinct ----------------Ctenophora? Sponges - Porifera • Mostly marine • Sessile animals • Lack true tissues; • Have only a few cell types, cells kind of independent • Most have no symmetry • Body resembles a sac perforated with holes, system of canals. • Strengthened by fibers of spongin, spicules Sponges have a variety of shapes Sponges Pores Choanocyte Amoebocyte (feeding cell) Skeletal Water fiber flow Central cavity Flagella Choanocyte in contact with an amoebocyte Sponges - Porifera • Sessile filter feeder • No mouth • Sac-like body, perforated by pores. • Interior lined by flagellated cells (choanocytes). Flagellated collar cells generate a current, draw water through the walls of the sponge where food is collected. • Amoeboid cells move around in the mesophyll and distribute food. Sponges - Porifera Grantia x.s. Sponge Reproduction Asexual reproduction • Fragmentation or by budding. • Sponges are capable of regeneration, growth of a whole from a small part. Sexual reproduction • Hermaphrodites, produce both eggs and sperm • Eggs and sperm released into the central cavity • Produces -

In the Ancient Times Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen Appreciated the Animal Nature of Tapeworms

1 In the ancient times Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen appreciated the animal nature of tapeworms. The Arabs susgested that segments passed with the faeces were a separate species of parasite from tapeworms: they called these segments the cucuribitini, after their similarity to cucumber seeds. Andry, in 1718, was first to illustrate the scolex of a tapeworm from a human. Sexually mature tapeworms live in the intestine or its diverticula ( rarely in the coelum) of all classes of vertebrates. These are a group of parasites which are fairly common in both domestic animals and wild animals, and humans. CLASS CESTODA This class differs from the Trematoda in having a tape-like body with no body cavity and alimentarty canal. There is a wide variation in length, ranging from a few milimeters to several meters. The body is segmented, each segment containing one and sometimes two sets of male and female reproductive organs. Almost all the tapeworms of veterinary importance are in the order Cyclophylidea, two exceptions being in the order Pseudophyllidea. During their life cycle, one or two ( or more ) intermediated host are required in each of which the tapeworm undergo a phase of their development. Order : Cyclophyllidea Family : Taenidae Genus : Taenia, Echinococcus Family : Anoplocephalidae Genus : Anoplocephala, Paranoplocephala, Monezia, Thysanosoma,Thysaniezia, Stilesia, Avitellina Family : Dilepididae Genus : Dipylidium , Amoebotaenia, Choanotaenia, Joyeuxiella, Diplopylidium Family : Paruterinidae Genus : Metroliasthes Family : Davaineidae -

Report on the Status of Mediterranean Chondrichthyan Species

United Nations Environment Programme Mediterranean Action Plan Regional Activity Centre For Specially Protected Areas REPORT ON THE STATUS OF MEDITERRANEAN CHONDRICHTHYAN SPECIES D. CEBRIAN © L. MASTRAGOSTINO © R. DUPUY DE LA GRANDRIVE © Note : The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of their frontiers or boundaries. © 2007 United Nations Environment Programme Mediterranean Action Plan Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) Boulevard du leader Yasser Arafat B.P.337 –1080 Tunis CEDEX E-mail : [email protected] Citation: UNEP-MAP RAC/SPA, 2007. Report on the status of Mediterranean chondrichthyan species. By Melendez, M.J. & D. Macias, IEO. Ed. RAC/SPA, Tunis. 241pp The original version (English) of this document has been prepared for the Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) by : Mª José Melendez (Degree in Marine Sciences) & A. David Macías (PhD. in Biological Sciences). IEO. (Instituto Español de Oceanografía). Sede Central Spanish Ministry of Education and Science Avda. de Brasil, 31 Madrid Spain [email protected] 2 INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION 3 3. HUMAN IMPACTS ON SHARKS 8 3.1 Over-fishing 8 3.2 Shark Finning 8 3.3 By-catch 8 3.4 Pollution 8 3.5 Habitat Loss and Degradation 9 4. CONSERVATION PRIORITIES FOR MEDITERRANEAN SHARKS 9 REFERENCES 10 ANNEX I. LIST OF CHONDRICHTHYAN OF THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA 11 1 1. -

Cestóides Pseudophyllidea Parasitos De Congro-Rosa, Genypterus

28 http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2014.192 Cestóides Pseudophyllidea parasitos de congro-rosa, Genypterus brasiliensis Regan, 1903 comercializados no estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Pseudophyllidea cestodes parasitic in cusk-eel, Genypterus brasiliensis Regan, 1903 purchased in the Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil Marcelo Knoff,* Sérgio Carmona de São Clemente,** Caroline Del Giudice de Andrada,*** Francisco Carlos de Lima,** Rodrigo do Espírito Santo Padovani,**** Michelle Cristie Gonçalves da Fonseca,* Renata Carolina Frota Neves,* Delir Corrêa Gomes* Resumo Entre outubro de 2002 e setembro de 2003 foram adquiridos 74 espécimes de Genypterus brasiliensis comercializados nos mercados dos municípios de Niterói e Rio de Janeiro. Estes foram necropsiados, filetados e seus órgãos analisados. Dos 74 espécimes analisados, 18 (24,3%) estavam parasitados por plerocercóides pertencentes ao gênero Diphyllobothrium Cobbold, 1858 na cavidade abdominal, serosa do intestino, intestino e musculatura, onde a intensidade média de infecção foi de 1,66 parasitos por peixe, a amplitude de variação da intensidade de infecção variou de um a sete e a abundância média foi de 0,40. Este é o primeiro registro de plerocercóides de Diphyllobothrium sp. em peixes teleósteos no Brasil. Palavras-chave: Diphyllobothrium sp., Genypterus brasiliensis, Brasil. Abstract Between October 2002 and September 2003 were collected 74 specimens of Genypterus brasiliensis purchased in the Niterói and Rio de Janeiro municipalities. Those were necropsied, fileted and their organs analyzed. From 74 specimens analyzed, 18 (24,3%) were parasitized by plerocercoids of Diphyllobothrium Cobbold, 1858 on the cavity abdominal, intestine serose, intestine and musculature, where the mean intensity of infection was 1,66 parasites per fish, the range was one to seven and mean abundance was 0,40. -

R E S E a R C H / M a N a G E M E N T Aquatic and Terrestrial Flatworm (Platyhelminthes, Turbellaria) and Ribbon Worm (Nemertea)

RESEARCH/MANAGEMENT FINDINGSFINDINGS “Put a piece of raw meat into a small stream or spring and after a few hours you may find it covered with hundreds of black worms... When not attracted into the open by food, they live inconspicuously under stones and on vegetation.” – BUCHSBAUM, et al. 1987 Aquatic and Terrestrial Flatworm (Platyhelminthes, Turbellaria) and Ribbon Worm (Nemertea) Records from Wisconsin Dreux J. Watermolen D WATERMOLEN Bureau of Integrated Science Services INTRODUCTION The phylum Platyhelminthes encompasses three distinct Nemerteans resemble turbellarians and possess many groups of flatworms: the entirely parasitic tapeworms flatworm features1. About 900 (mostly marine) species (Cestoidea) and flukes (Trematoda) and the free-living and comprise this phylum, which is represented in North commensal turbellarians (Turbellaria). Aquatic turbellari- American freshwaters by three species of benthic, preda- ans occur commonly in freshwater habitats, often in tory worms measuring 10-40 mm in length (Kolasa 2001). exceedingly large numbers and rather high densities. Their These ribbon worms occur in both lakes and streams. ecology and systematics, however, have been less studied Although flatworms show up commonly in invertebrate than those of many other common aquatic invertebrates samples, few biologists have studied the Wisconsin fauna. (Kolasa 2001). Terrestrial turbellarians inhabit soil and Published records for turbellarians and ribbon worms in leaf litter and can be found resting under stones, logs, and the state remain limited, with most being recorded under refuse. Like their freshwater relatives, terrestrial species generic rubric such as “flatworms,” “planarians,” or “other suffer from a lack of scientific attention. worms.” Surprisingly few Wisconsin specimens can be Most texts divide turbellarians into microturbellarians found in museum collections and a specialist has yet to (those generally < 1 mm in length) and macroturbellari- examine those that are available. -

Behaviour of Roach (Rutilus Mtilus L.) Altered by Ligula Intestinalis (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea): a Field Demonstration

Freshwuter Biology (2001) 46, 1219-1227 Behaviour of roach (Rutilus mtilus L.) altered by Ligula intestinalis (Cestoda: Pseudophyllidea): a field demonstration GÉRALDINE LOOT," SÉBASTIEN BROSSE,*,SOVAN LEK" and JEAN-FRANçOIS GUÉGANt "CESAC, UMR CNRS 5576, Bâtiment NR3, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulbuse Cedex 4, Frame i tCerztre $Etudes sur le Polymorphisme des Micro-orgaizismes, Centre IRD de Montpellier, UMR CNRS-IRD 9926, Montpellier Cedex 1, France J 6 SUMMARY 3 1. We studied the influence of a cestode parasite, the tapeworm Ligula intestinalis (L.) on roach (Xufilusrutilus L.) spatial occupancy in a French reservoir (Lake Pareloup, South- west of France). 2. Fish host age, habitat use and parasite occurrence and abundance were determined during a 1 year cycle using monthly gill-net catches. Multivariate analysis [generalized linear models (GLIM)], revealed significant relationships (P < 0.05) between roach age, its spatial occupancy and parasite occurrence and abundance. 3. Three-year-old roach were found to be heavily parasitized and their location toward the bank was significantly linked to parasite occurrence and abundance. Parasitized fish, considering both parasite occurrence and abundance, tended to occur close to the bank between July and December. On the contrary, between January and June no significant relationship was found. 4. These behavioural changes induced by the parasite may increase piscivorous bird encounter rate and predation efficiency on parasitized roach and therefore facilitate completion of the parasite's life cycle. Keywords: host behaviour, Ligula intestinalis, parasite-mediated manipulation, parasitism, Rutilus rutilus enon 'Parasite Increased Trophic Transmission (PITT)' Introduction which results from an evolutionary process that Many trophically transmitted parasites alter their increases parasite fitness. -

AQUACULTURE in the ENSENADA REGION of NORTHERN BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO José A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology - Publications Stamford 4-1-2008 MARINE SCIENCE ASSESSMENT OF CAPTURE-BASED TUNA (Thunnus orientalis) AQUACULTURE IN THE ENSENADA REGION OF NORTHERN BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO José A. Zertuche-González Universidad Autonoma de Baja California Ensenada Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki Centro de Investigacion Cientifica y de Educacion Superior de Ensenada (CICESE) Juan G. Vaca Rodriguez Universidad Autonoma de Baja California Ensenada Raul del Moral Simanek Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT) Ensenada Charles Yarish University of Connecticut, [email protected] Recommended Citation Zertuche-González, José A.; Sosa-Nishizaki, Oscar; Vaca Rodriguez, Juan G.; del Moral Simanek, Raul; Yarish, Charles; and Costa- Pierce, Barry A., "MARINE SCIENCE ASSESSMENT OF CAPTURE-BASED TUNA (Thunnus orientalis) AQUACULTURE IN THE ENSENADA REGION OF NORTHERN BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO" (2008). Publications. 1. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/ecostam_pubs/1 See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/ecostam_pubs Part of the Marine Biology Commons Authors José A. Zertuche-González, Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki, Juan G. Vaca Rodriguez, Raul del Moral Simanek, Charles Yarish, and Barry A. Costa-Pierce This report is available at OpenCommons@UConn: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/ecostam_pubs/1 1 MARINE SCIENCE ASSESSMENT OF CAPTURE-BASED TUNA (Thunnus orientalis) AQUACULTURE IN THE ENSENADA REGION OF NORTHERN BAJA CALIFORNIA,