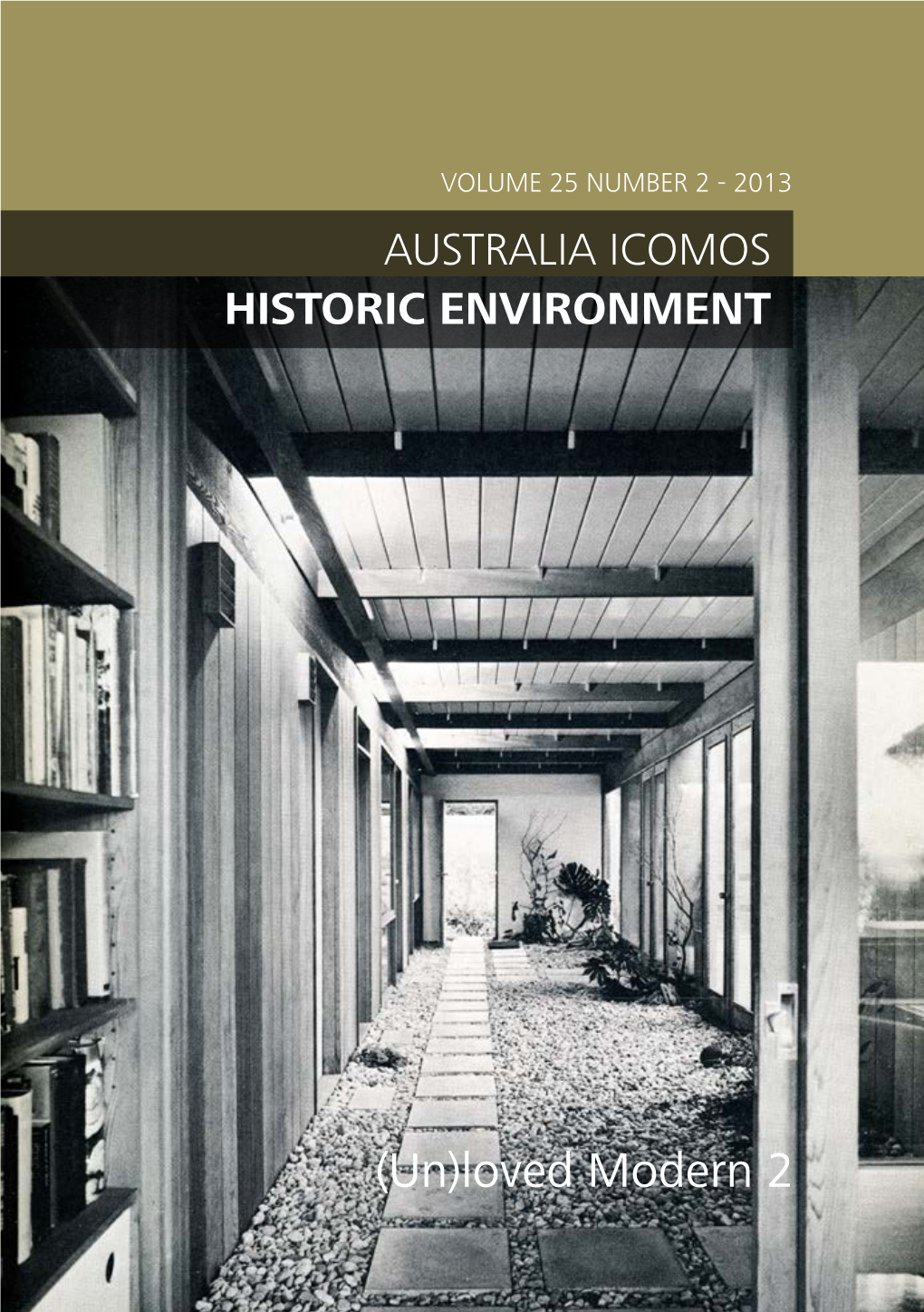

(Un)Loved Modern 2 AUSTRALIA ICOMOS HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne

St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne – Aikenhead Wing Proposed demolition Referral report and Heritage Impact Statement 27 & 31 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy July 2021 Prepared by Prepared for St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne Quality Assurance Register The following quality assurance register documents the development and issue of this report prepared by Lovell Chen Pty Ltd in accordance with our quality management system. Project no. Issue no. Description Issue date Approval 8256.03 1 Draft for review 24 June 2021 PL/MK 8256.03 2 Final Referral Report and HIS 1 July 2021 PL Referencing Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced as endnotes or footnotes and/or in figure captions. Reasonable effort has been made to identify and acknowledge material from the relevant copyright owners. Moral Rights Lovell Chen Pty Ltd asserts its Moral right in this work, unless otherwise acknowledged, in accordance with the (Commonwealth) Copyright (Moral Rights) Amendment Act 2000. Lovell Chen’s moral rights include the attribution of authorship, the right not to have the work falsely attributed and the right to integrity of authorship. Limitation Lovell Chen grants the client for this project (and the client’s successors in title) an irrevocable royalty- free right to reproduce or use the material from this report, except where such use infringes the copyright and/or Moral rights of Lovell Chen or third parties. This report is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Lovell Chen Pty Ltd and its Client. Lovell Chen Pty Ltd accepts no liability or responsibility for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. -

Land at 10 King Henry's Road, London, NW3

Our ref: APP/X5210/C/18/3219239 Rebecca Anderson Iceni Projects Da Vinci House 44 Saffron Hill Farringdon EC1N 8FH 12 March 2020 Dear Madam, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTIONS 174 & 177 APPEAL MADE BY THE GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA LAND AT 10 KING HENRY’S ROAD, LONDON, NW3 3RP ENFORCEMENT REF: EN18/0027 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of Mr K L Williams BA, MA, MRTPI, who held a public local inquiry on 24 September and 11 October into your client’s appeal against an enforcement notice issued on 16 November 2018, by the London Borough of Camden. The enforcement notice is summarised by the Inspector as follows: • The breach of planning control as alleged in the notice is a change of use from 2 residential units (Class 3) to museum (Class D1) including the erection of a single storey rear conservatory, alteration to boundary treatment including addition of metal railing and alterations to existing entrance steps including the installation of a disabled platform lift to access the upper ground floor. • The requirements of the notice are to cease the use of the memorial/museum (Class D1) and revert to previous use and layout as 2 residential units (Class C3). • The period for compliance with the requirements is 6 months. 2. On 20 September 2019, this appeal was recovered for the Secretary of State's determination, in pursuance of section 174 of, and paragraph 2(a) of, the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. -

PLANNING PANELS VICTORIA Expert Heritage Evidence

PLANNING PANELS VICTORIA Melbourne Planning Scheme Amendment C365 Heritage Overlay HO1205 Subject Site: “Chart House”, No. 372 - 378 Little Bourke Street Melbourne Expert Heritage Evidence Prepared for Berjaya Developments Pty Ltd By Robyn Riddett Director Anthemion Consultancies POB18183 Collins Street East Melbourne 8003 Tel. +61 3 9495 6389 Email: [email protected] December 2019 “Chart House” No. 372 - 378 Little Bourke Street, Melbourne 1.0 Introduction 1. I have been instructed by Best Hooper, on behalf of Berjaya Developments Pty Ltd, to prepare expert heritage evidence which addresses the heritage aspects of the proposal to grade the site as “Contibutory”, as a consequence of the Guildford and Hardware Laneways Heritage Study prepared by Lovell Chen in May 2017, as a consequence of Melbourne Planning Scheme Amendment C365. 2. The previous Property Schedule included in the Guildford & Hardware Laneways Precinct Citation graded the building as Contributory. In effect it graded the east wall abutting Niagara Lane but not the façade addressing Little Bourke Street which Lovell Chen had indicated was not of any significance. Subsequently the Amendment C271 Panel recommended that “Chart House” be included within HO1205 with a Non-contributory grading. When HO1205 came into effect on 12 August 2019, No. 372 – 378 Little Bourke Street was included within HO1205 but with a Contributory, rather than with a Non- contributory grading and on an interim basis as a consequence of Amendment C355melb. This change in grading appears to have been influenced by correspondence from Melbourne Heritage Action which put forward new information about “Chart House”. It is now proposed, as a consequence of Amendment C365melb, to include No. -

Australia's National Heritage

High Court–National Gallery Precinct AUSTRALI A N C A PI TA L T E R R ITORY The High Court–National Gallery Precinct is significant as a group of public buildings and landscape conceived as a single entity. The complex is stylistically integrated in terms of architectural forms and finishes, and as an ensemble of freestanding buildings in a cohesive landscape setting. The Precinct occupies a 16-hectare site in the north-east corner of the Parliamentary Zone. It includes the High Court, National Gallery of Australia and the Gallery’s Sculpture Garden. The landscape brief from the National Capital National Gallery of Australia Development Commission required that the High Court, National Gallery and surrounding landscape become a chambers. A waterfall designed by Robert Woodward and single precinct in visual terms, with the High Court as constructed from South Australian speckled granite runs the dominant element to be open to views from Lake the full length of the entry ramp. Burley Griffin. The National Gallery is a complex building of varied The Precinct is a synthesis of design, aesthetic, social and levels and spaces arranged on four floors of approximately environment values with a clear Australia identity. This 23 000 square metres. Like the High Court, much of the is represented in the pattern of functional columns and building is made of reinforced bush-hammered concrete, towers in the architectural elements, the sculptures of the an example of the architect’s philosophy that concrete has national collection in a landscaped setting, and the high as much integrity as stone. -

National Architecture Award Winners 1981 – 2019

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2019 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 81 2019 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Yagan Square (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Lyons in collaboration with Iredale Pedersen Hook and landscape architects ASPECT Studios COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Dangrove (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Breathe Architecture Private Women’s Club (VIC) National Award for Commercial Architecture Kerstin Thompson Architects EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Primary School (NSW) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture BVN Braemar College Stage 1, Middle School National Award for Educational Architecture Hayball Adelaide Botanic High School (SA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Cox Architecture and DesignInc QUT Creative Industries Precinct 2 (QLD) National Commendation for Educational Architecture KIRK and HASSELL (Architects in Association) ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Sails in the Desert (NT) National Award for Enduring Architecture Cox Architecture HERITAGE Premier Mill Hotel (WA) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Spaceagency architects Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Heritage Breathe Architecture Flinders Street Station Façade Strengthening & Conservation National Commendation for Heritage (VIC) Lovell Chen Sacred Heart Building Abbotsford Convent Foundation -

The Garden of Australian Dreams: the Moral Rights of Landscape Architects

EDWARD ELGAR THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER SENIOR LECTURER ACIPA, FACULTY OF LAW, THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACIPA, Faculty Of Law, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 0200 Work Telephone Number: (02) 61254164 E-Mail Address: [email protected] THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER* * Matthew Rimmer, BA (Hons)/ LLB (Hons) (ANU), PhD (UNSW), is a Senior Lecturer at ACIPA, the Faculty of Law, the Australian National University. The author is grateful for the comments of Associate Professor Richard Weller, Tatum Hands, Dr Kathy Bowrey, Dr Fiona Macmillan and Kimberlee Weatherall. He is also thankful for the research assistance of Katrina Gunn. 1 Prominent projects such as National Museums are expected to be popular spectacles, educational narratives, tourist attractions, academic texts and crystallisations of contemporary design discourse. Something for everyone, they are also self-consciously set down for posterity and must at some level engage with the aesthetic and ideological risks of national edification. Richard Weller, designer of the Garden of Australian Dreams1 Introduction This article considers the moral rights controversy over plans to redesign the landscape architecture of the National Museum of Australia. The Garden of Australian Dreams is a landscaped concrete courtyard.2 The surface offers a map of Australia with interwoven layers of information. It alludes to such concepts as the Mercator Grid, parts of Horton’s Map of the linguistic boundaries of Indigenous Australia, the Dingo Fence, the 'Pope’s Line', explorers’ tracks, a fibreglass pool representing a suburban swimming pool, a map of Gallipoli, graphics common to roads, and signatures or imprinted names of historical identities.3 There are encoded references to the artistic works of iconic Australian painters such as Jeffrey Smart, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, and Gordon Bennett. -

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One

Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria: Stage One Volume 1: Contextual Overview, Methodology, Lists & Appendices Prepared for Heritage Victoria October 2008 This report has been undertaken in accordance with the principles of the Burra Charter adopted by ICOMOS Australia This document has been completed by David Wixted, Suzanne Zahra and Simon Reeves © heritage ALLIANCE 2008 Contents 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Context ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Project Brief .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Contextual Overview .................................................................................................................. 7 3.0 Places of Potential State Significance .................................................................................... 35 3.1 Identification Methodology .......................................................................................................... 35 3.2 Verification of Places .................................................................................................................. 36 3.3 Application -

CITY of BOROONDARA Review of B-Graded Buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn

CITY OF BOROONDARA Review of B-graded buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn Prepared for City of Boroondara January 2007 Revised June 2007 VOLUME 4 BUILDINGS NOT RECOMMENDED FOR THE HERITAGE OVERLAY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 Main Report VOLUME 2 Individual Building Data Sheets – Kew VOLUME 3 Individual Building Data Sheets – Camberwell and Hawthorn VOLUME 4 Individual Building Data Sheets for buildings not recommended for the Heritage Overlay LOVELL CHEN 1 Introduction to the Data Sheets The following data sheets have been designed to incorporate relevant factual information relating to the history and physical fabric of each place, as well as to give reasons for the recommendation that they not be included in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay in the Boroondara Planning Scheme. The following table contains explanatory notes on the various sections of the data sheets. Section on data sheet Explanatory Note Name Original and later names have been included where known. In the event no name is known, the word House appears on the data sheet Reference No. For administrative use by Council. Building type Usually Residence, unless otherwise stated. Address Address as advised by Council and checked on site. Survey Date Date when site visited. Noted here if access was requested but not provided. Grading Grading following review (C or Ungraded). In general, a C grading reflects a local level of significance albeit a comparatively low level when compared with other examples. In some cases, such buildings may not have been extensively altered, but have been assessed at a lower level of local significance. In other cases, buildings recommended to be downgraded to C may have undergone alterations or additions since the earlier heritage studies. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement: Exchanges Between Greece and Britain (1876-1930)

The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) M.Phil thesis Mary Greensted University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Introduction 1 1. The Arts and Crafts Movement: from Britain to continental 11 Europe 2. Arts and Crafts travels to Greece 27 3 Byzantine architecture and two British Arts and Crafts 45 architects in Greece 4. Byzantine influence in the architectural and design work 69 of Barnsley and Schultz 5. Collections of Greek embroideries in England and their 102 impact on the British Arts and Crafts Movement 6. Craft workshops in Greece, 1880-1930 125 Conclusion 146 Bibliography 153 Acknowledgements 162 The Arts and Crafts Movement: exchanges between Greece and Britain (1876-1930) Introduction As a museum curator I have been involved in research around the Arts and Crafts Movement for exhibitions and publications since 1976. I have become both aware of and interested in the links between the Movement and Greece and have relished the opportunity to research these in more depth. It has not been possible to undertake a complete survey of Arts and Crafts activity in Greece in this thesis due to both limitations of time and word constraints. -

East of England

EastEast of of England England Berwick-upon-Tweed Lindisfarne Castle Giant’s Causeway Carrick-a-Rede Cragside Downhill Coleraine Demesne and Hezlett House Morpeth Wallington LONDONDERRY Blyth Seaton Delaval Hall Whitley Bay Tynemouth Newcastle Upon Tyne M2 Souter Lighthouse Jarrow and The Leas Ballymena Cherryburn Gateshead Gray’s Printing Larne Gibside Sunderland Press Carlisle Consett Washington Old Hall Houghton le Spring M22 Patterson’s M6 Springhill Spade Mill Carrickfergus Durham M2 Newtownabbey Brandon Peterlee Wellbrook Cookstown Bangor Beetling Mill Wordsworth House Spennymoor Divis and the A1(M) Hartlepool BELFAST Black Mountain Newtownards Workington Bishop Auckland Mount Aira Force Appleby-in- Redcar and Ullswater Westmorland Stewart Stockton- Middlesbrough M1 Whitehaven on-Tees The Argory Strangford Ormesby Hall Craigavon Lough Darlington Ardress House Rowallane Sticklebarn and Whitby Castle Portadown Garden The Langdales Coole Castle Armagh Ward Wray Castle Florence Court Beatrix Potter Gallery M6 and Hawkshead Murlough Northallerton Crom Steam Yacht Gondola Hill Top Kendal Hawes Rievaulx Scarborough Sizergh Terrace Newry Nunnington Hall Ulverston Ripon Barrow-in-Furness Bridlington Fountains Abbey A1(M) Morecambe Lancaster Knaresborough Beningbrough Hall M6 Harrogate York Skipton Treasurer’s House Fleetwood Ilkley Middlethorpe Hall Keighley Yeadon Tadcaster Clitheroe Colne Beverley East Riddlesden Hall Shipley Blackpool Gawthorpe Hall Nelson Leeds Garforth M55 Selby Preston Burnley M621 Kingston Upon Hull M65 Accrington -

Who Is Council Housing For?

‘We thought it was Buckingham Palace’ ‘Homes for Heroes’ Cottage Estates Dover House Estate, Putney, LCC (1919) Cottage Estates Alfred and Ada Salter Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey Metropolitan Borough Council (1924) Tenements White City Estate, LCC (1938) Mixed Development Somerford Grove, Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Neighbourhood Units The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, LCC (1951) Post-War Flats Spa Green Estate, Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Berthold Lubetkin Post-War Flats Churchill Gardens Estate, City of Westminster (1951) Architectural Wars Alton East, Roehampton, LCC (1951) Alton West, Roehampton, LCC (1953) Multi-Storey Housing Dawson’s Heights, Southwark Borough Council (1972) Kate Macintosh The Small Estate Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham, LCC (1965) Low-Rise, High Density Lambeth Borough Council Central Hill (1974) Cressingham Gardens (1978) Camden Borough Council Low-Rise, High Density Branch Hill Estate (1978) Alexandra Road Estate (1979) Whittington Estate (1981) Goldsmith Street, Norwich City Council (2018) Passivhaus Mixed Communities ‘The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.’ Pat Hayes, LB Lewisham, Director of Regeneration You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view… We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street – the living tapestry of a mixed community.