St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornishness and Englishness: Nested Identities Or Incompatible Ideologies?

CORNISHNESS AND ENGLISHNESS: NESTED IDENTITIES OR INCOMPATIBLE IDEOLOGIES? Bernard Deacon (International Journal of Regional and Local History 5.2 (2009), pp.9-29) In 2007 I suggested in the pages of this journal that the history of English regional identities may prove to be ‘in practice elusive and insubstantial’.1 Not long after those words were written a history of the north east of England was published by its Centre for Regional History. Pursuing the question of whether the north east was a coherent and self-conscious region over the longue durée, the editors found a ‘very fragile history of an incoherent and barely self-conscious region’ with a sense of regional identity that only really appeared in the second half of the twentieth century.2 If the north east, widely regarded as the most coherent English region, lacks a historical identity then it is likely to be even more illusory in other regions. Although rigorously testing the past existence of a regional discourse and finding it wanting, Green and Pollard’s book also reminds us that history is not just about scientific accounts of the past. They recognise that history itself is ‘an important element in the construction of the region … Memory of the past is deployed, selectively and creatively, as one means of imagining it … We choose the history we want, to show the kind of region we want to be’.3 In the north east that choice has seemingly crystallised around a narrative of industrialization focused on the coalfield and the gradual imposition of a Tyneside hegemony over the centuries following 1650. -

PLANNING PANELS VICTORIA Expert Heritage Evidence

PLANNING PANELS VICTORIA Melbourne Planning Scheme Amendment C365 Heritage Overlay HO1205 Subject Site: “Chart House”, No. 372 - 378 Little Bourke Street Melbourne Expert Heritage Evidence Prepared for Berjaya Developments Pty Ltd By Robyn Riddett Director Anthemion Consultancies POB18183 Collins Street East Melbourne 8003 Tel. +61 3 9495 6389 Email: [email protected] December 2019 “Chart House” No. 372 - 378 Little Bourke Street, Melbourne 1.0 Introduction 1. I have been instructed by Best Hooper, on behalf of Berjaya Developments Pty Ltd, to prepare expert heritage evidence which addresses the heritage aspects of the proposal to grade the site as “Contibutory”, as a consequence of the Guildford and Hardware Laneways Heritage Study prepared by Lovell Chen in May 2017, as a consequence of Melbourne Planning Scheme Amendment C365. 2. The previous Property Schedule included in the Guildford & Hardware Laneways Precinct Citation graded the building as Contributory. In effect it graded the east wall abutting Niagara Lane but not the façade addressing Little Bourke Street which Lovell Chen had indicated was not of any significance. Subsequently the Amendment C271 Panel recommended that “Chart House” be included within HO1205 with a Non-contributory grading. When HO1205 came into effect on 12 August 2019, No. 372 – 378 Little Bourke Street was included within HO1205 but with a Contributory, rather than with a Non- contributory grading and on an interim basis as a consequence of Amendment C355melb. This change in grading appears to have been influenced by correspondence from Melbourne Heritage Action which put forward new information about “Chart House”. It is now proposed, as a consequence of Amendment C365melb, to include No. -

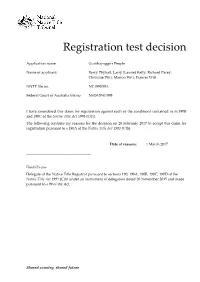

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Gumbaynggirr People Name of applicant Barry Phyball, Larry (Laurie) Kelly, Richard Pacey, Christine Witt, Marion Witt, Frances Witt NNTT file no. NC1998/015 Federal Court of Australia file no. NSD6104/1998 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). The following contains my reasons for the decision on 28 February 2017 to accept this claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Date of reasons: 1 March 2017 ___________________________________ Heidi Evans Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) under an instrument of delegation dated 20 November 2015 and made pursuant to s 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] This document sets out my reasons, as the delegate of the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar), for the decision to accept the claim for registration pursuant to s 190A of the Act. [2] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the amended Gumbaynggirr People claimant application to the Registrar on 7 November 2016 pursuant to s 64(4) of the Act. This has triggered the Registrar’s duty to consider the claim made in the application under s 190A of the Act. [3] I am satisfied that neither subsection 190A(1A) nor subsection 190A(6A) apply to this claim. This is because the application was not amended as the result of an order of the Court, nor do the nature of the particular amendments to the application fall within the scope of s 190A(6A)(d). -

C:\Documents and Settings\Chris Dunkerley\My Documents\Excel

CORNISH ASSOCIATION OF NSW - MEMBERS LENDING & RESEARCH LIBRARY - Jan 2008 Search using Edit, Find in this page (Firefox) For more information or to borrow contact Eddie or Eileen Lyon on: (02) 9349 1491 or Email: [email protected] Id No BOOK NAME AUTHOR DESCRIPTION 1 Yesterday's Town: St Ives Noall Cyril Book - illustrated history 2 King Arthur Country in Cornwall Duxbury & Williams Book - information 3 Story of St Ives, The Noall Cyril Book 4 St Ives in the 1800's Laity R.P. Book 5 Cornish Surnames, A Handbook of G. Pawley White Book 6 Cornish Pioneers of Ballarat Dell & Menhennet Book 7 Kernewek for Kids Franklin Sharon Book - Copper Triangle Puzzles, Stories 8 Australian Celtic Journal Vol.One Darlington J Journal 9 Microform Collection Index (OUT OF CIRCULATION) Aust. Soc of Genealogy Journal 10 Where Now Cousin Jack? Hopkins Ruth Book 11 Cornwall - A Genealogical Bibliography Raymond Stuart Journal LOST 12 Penwith - The Illustrated Past Noall Cyril Book 13 St Ives, The Book of Noall Cyril Book - pictorial history LOST IN FIRE 14 Cornish Names Dexter T.F.G. Book 15 Scilly and the Scillonians Read A.H. & Son Book - pictorial history 16 Shipwrecks at Land's End Larn & Mills Book 17 Minerals, Rocks and Gemstones in Cornwall Rogers Cedric Book - collector’s guide 18 King Arthur, Tintagel Castle & Celtic Monuments Tintagel Parish Council Book 19 Shipwrecks on the Isles of Scilly Gibson F.E. Book 20 Which Francis Symonds Symonds John Symonds history - Cornwall and Australia 21 St Ives, The Beauty of Badger H.G. Illustration Booklet 22 Little Land of Cornwall, The Rowse A.L. -

Architecture Creating Connections Recognised in 2020 Victorian Architecture Awards Shortlist

Architecture creating connections recognised in 2020 Victorian Architecture Awards shortlist The best of Victoria’s architecture, showcasing the immense value architects add when embedded end to end in a project, has been revealed with the release today of the 2020 Victorian Architecture Awards shortlist. The awards program, run by the Victorian Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects, features a shortlist recognising architecture in the public realm, residential sector, regional areas, embedded sustainability and much more. Spread across 14 categories, 108 entries have made the shortlist which encompasses 76 individual projects. Victorian Chapter President Amy Muir says the shortlisted projects define the significant role that quality built outcomes have in creating sustainable, resilient buildings that can endure for generations. The selected projects go beyond the parameters of the brief to deliver compelling results. ‘This year’s shortlisted projects are exemplars of the outcomes that can be achieved when architects are engaged in the entire process, resulting in a strong collaboration between client, consultants and contracted builders,’ said Ms Muir. ‘These projects are leading examples of how architects elevate quality through carefully considered outcomes in the building process. The selected projects create a lasting legacy that enable architecture to be accessed more broadly throughout the community. ‘During these strange times we are thrilled to celebrate architecture that continues to challenge the status quo. In -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

Heritage Precincts: History and Significance

MELBOURNE PLANNING SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 1 The City of Melbourne 5 Background History 5 City of Melbourne Summary Statement of Significance 11 2. Carlton Heritage Precinct 13 Background History 13 Statement of Significance for Carlton Heritage Precinct 16 3. East Melbourne Heritage Precinct including Jolimont and the Parliamentary Precinct 19 Background History 19 0 Statement of Significance for East Melbourne Heritage Precinct including Jolimont and the Parliamentary Precinct 22 4. Kensington & Flour Milling Heritage Precinct 27 Background History 27 Statement of Significance for Kensington & Flour Milling Heritage Precinct 29 5. North & West Melbourne Heritage Precinct 31 Background History 31 Statement of Significance for North & West Melbourne Heritage Precinct 34 6. Parkville Heritage Precinct 37 Background History 37 Statement of Significance for Perky'Ile Heritage Precinct 40 7. South Yarra Heritage Precinct 43 Background History 43 Statement of Significance for South Yarra Heritage Precinct 46 8. Bank Place Heritage Precinct 50 Background History 50 Statement of Significance for Bank Place Heritage Precinct 52 9. Bourke Hill Heritage Precinct 54 Background History 54 Statement of Significance for Bourke Hill Heritage Precinct 56 10. Collins Street East Heritage Precinct59 Background History 59 Statement of Significance for Collins Street East Heritage Precinct 61 REFERENCE DOCUMENT - PAGE 2 OF 94 MELBOURNE PLANNING SCHEME 11. Flinders Lane Heritage Precinct 64 Background History 64 Statement of Significance for Flinders Lane Heritage Precinct 65 12. Flinders Street Heritage Precinct 68 Background History 68 Statement of Significance for Flinders Street Heritage Precinct 69 13. Guildford Lane Heritage Precinct 72 Background History 72 Statement of Significance for Guildford Lane Heritage Precinct 73 14. -

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review

City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Place name: B.A.L.M. Paints Factory Citation No: Administration Building 8 (former) Other names: - Address: 2 Salmon Street, Port Heritage Precinct: None Melbourne Heritage Overlay: HO282 Category: Factory Graded as: Significant Style: Interwar Modernist Victorian Heritage Register: No Constructed: 1937 Designer: Unknown Amendment: C29, C161 Comment: Revised citation Significance What is significant? The former B.A.L.M. Paints factory administration building, to the extent of the building as constructed in 1937 at 2 Salmon Street, Port Melbourne, is significant. This is in the European Modernist manner having a plain stuccoed and brick façade with fluted Art Deco parapet treatment and projecting hood to the windows emphasising the horizontality of the composition. There is a tower towards the west end with a flag pole mounted on a tiered base in the Streamlined Moderne mode and porthole motif constituting the key stylistic elements. The brickwork between the windows is extended vertically through the cement window hood in ornamental terminations. Non-original alterations and additions to the building are not significant. How is it significant? The former B.A.L.M. Paints factory administration building at 2 Salmon Street, Port Melbourne is of local historic, architectural and aesthetic significance to the City of Port Phillip. City of Port Phillip Heritage Review Citation No: 8 Why is it significant? It is historically important (Criterion A) as evidence of the importance of the locality as part of Melbourne's inner industrial hub during the inter-war period, also recalling the presence of other paint manufacturers at Port Melbourne including Glazebrooks, also in Williamstown Road. -

Paolo Giorza and Music at Sydney's 1879 International Exhibition

‘Pleasure of a High Order:’ Paolo Giorza and Music at Sydney’s 1879 International Exhibition Roslyn Maguire As Sydney’s mighty Exhibition building took shape, looking to the harbour from an elevated site above the Botanic Gardens, anxiety and excitement mounted. This was to be the first International Exhibition held outside Europe or America and musical entertainment was to be its greatest attraction.1 An average of three thousand people would attend each week day and as recent studies have shown, Sydney’s International Exhibition helped initiate reforms to education, town planning, technologies, photography, manufacturing and patronage of the arts, music and literature.2 Although under construction since January 1879, it was mid May before the Exhibition’s influential Executive Commissioner Patrick Jennings3 announced the appointment of his friend, Milanese composer Paolo Giorza4 as musical director: [H]is credentials are of such a nature both as a conductor, composer and artist, that I could not justly pass them over. I think that he should also be authorised to compose a march and cantata for the opening ceremony … Signor Giorza offers to give his exclusive services as composer and director and performer on the organ and to organise a competent orchestra of local artists for promenade concerts, and to conduct the same.5 The extent of Jennings’s personal interest in Exhibition music is evident in this report publicising Giorza’s appointment. It amounts to one of the colony’s most interesting cultural documents for the ideas, attitudes and objectives it reveals, including consideration of whether an ‘Australian School of Music, as distinguished from any of the well-defined schools’ existed. -

Religion, Cultural Diversity and Safeguarding Australia

Cultural DiversityReligion, and Safeguarding Australia A Partnership under the Australian Government’s Living In Harmony initiative by Desmond Cahill, Gary Bouma, Hass Dellal and Michael Leahy DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS and AUSTRALIAN MULTICULTURAL FOUNDATION in association with the WORLD CONFERENCE OF RELIGIONS FOR PEACE, RMIT UNIVERSITY and MONASH UNIVERSITY (c) Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Intellectual Property Branch, Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or at http:www.dcita.gov.au The statement and views expressed in the personal profiles in this book are those of the profiled person and are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth, its employees officers and agents. Design and layout Done...ByFriday Printed by National Capital Printing ISBN: 0-9756064-0-9 Religion,Cultural Diversity andSafeguarding Australia 3 contents Chapter One Introduction . .6 Religion in a Globalising World . .6 Religion and Social Capital . .9 Aim and Objectives of the Project . 11 Project Strategy . 13 Chapter Two Historical Perspectives: Till World War II . 21 The Beginnings of Aboriginal Spirituality . 21 Initial Muslim Contact . 22 The Australian Foundations of Christianity . 23 The Catholic Church and Australian Fermentation . 26 The Nonconformist Presence in Australia . 28 The Lutherans in Australia . 30 The Orthodox Churches in Australia . -

St Vincent Place East (South Melbourne) – H0441

Port Phillip Heritage Review 6.32 St Vincent Place East (South Melbourne) – H0441 Existing Designations: Heritage Council Register: nil National Estate Register: nil National Trust Register: nil Previous Heritage Studies: Conservation Study 1975: Precincts 3 and 6 (part) Conservation Study 1987: UC1: Precinct C Heritage Review 2000: HO3 (part) 6.32.1 History The residential estate known as St Vincent Place was created in 1854 as an extension to the original Emerald Hill town plan, which had been laid out two years earlier. Its striking design, attributed to Andrew Clarke (then Surveyor-General of Victoria), was based on the traditional Circus or Crescent developments of Georgian London, where housing was laid out in a curve around a central public reserve. Clarke’s original scheme, as depicted on an 1855 survey map, proposed a rectangular estate with curved ends, defined by Park Street, Howe Crescent, Bridport Street and Merton Crescent. It comprised two concentric rows of residential allotments with a laneway between, enclosing an open space with two small elliptical reserves flanking a longer round-ended reserve, the latter with indications of landscaping and a network of curved pathways. This grand scheme, however, was not realised at that time, and would subsequently be revised when it was decided to run the new St Kilda railway line parallel to Ferrars Street, which effectively split the proposed St Vincent Place estate into two parts. A revised design, prepared by Clement Hodgkinson in 1857, proposed the development of each portion as a discrete subdivision. The smaller eastern portion, east of the new railway line, became a stand-alone estate with two streets that curved around a central semi-circular reserve alongside the railway cutting. -

State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston Street, Melbourne Conservation

State Library of Victoria 328 Swanston Street, Melbourne Conservation Management Plan – Volume 1 State Library of Victoria Complex 328 Swanston Street, Melbourne Conservation Management Plan Volume 1: Conservation Analysis and Policy Prepared for the State Library of Victoria February 2011 Date Document status Prepared by April 2009 Final draft Lovell Chen October 2010 Wheeler Centre component Lovell Chen update issued February 2011 Final report Lovell Chen TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF FIGURES iii LIST OF TABLES vii CONSULTANTS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and Brief 1 1.2 Report Structure and Format 1 1.3 Location 2 1.4 Heritage Listings and Statutory Controls 4 1.5 Terminology 5 2.0 HISTORY 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 The Public Library 7 2.3 The Intercolonial Exhibition 21 2.4 The National Gallery 27 2.5 The Industrial and Technological Museum 33 2.6 The Natural History Museum 37 2.7 Relocation of the Museum and the State Library Master Plan 41 3.0 PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT AND ANALYSIS 45 3.1 Introduction 45 3.2 Stages of Construction 46 3.3 Construction types and detailing 72 3.4 Survey of Building Fabric and Room Data Sheets 77 3.5 Services 82 4.0 INVESTIGATION OF DECORATIVE FINISHES 83 4.1 Methodology 83 4.2 Review Comment 83 4.3 1985 Investigation Results 83 4.4 The Decorative Schemes 93 5.0 FURNITURE SURVEY 95 5.1 Introduction and Overview 95 5.2 Summary of 1985 Survey Results 95 5.3 Current Furniture Holdings 96 6.0 ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 99 6.1 Introduction and Overview