Gariwo, the Forest of the Righteous 11 May 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Ángel De Budapest Egy Angyal Budapesten

EL ÁNGEL DE BUDAPEST EGY ANGYAL BUDAPESTEN EL ÁNGEL DE BUDAPEST EGY ANGYAL BUDAPESTEN 4 En memoria del diplomático español Ángel Sanz Briz Justo entre las Naciones (1910-1980), quien en 1944, junto con los empleados y colaboradores de la Legación de España en Budapest, salvó la vida de más de 5.000 judíos húngaros de la persecución del nazismo. “No te quedes inactivo cuando derraman la sangre de tu prójimo” (Levítico 19/16.) Embajada de España en Budapest (Hungría), 2015 IN MEMORIAM Ángel Sanz Briz a „Világ Igaza” (1910-1980), spanyol diplomata, 1944-ben Budapesten a Span- yol Követség munkatársaival és segítőivel közösen több mint 5000 magyar zsidó életét mentette meg a náci üldöztetéstől”. „…ne légy tétlen, ha felebarátaid vérét ontják” (3Móz. 19:16) „ Spanyol Nagykövetség, 2015 5 5 Antisemitismo, Antiszemitizmus, persecución üldöztetés y deportaciones és deportálások Al poco de comenzar la segunda guerra mundial Kevéssel a II. világháború kitörése után, a háttérben y con el telón de fondo del auge del nazismo y del Európában a nácizmus és az antiszemitizmus antisemitismo en Europa, se promulgaron una se- megerősödése mellett, számos olyan törvényt rie de leyes en Hungría contra la población judía hírdettek ki Magyarországon, amelyek szörnyű que les impuso unas condiciones terribles. Así lo helyzetbe hozták a zsidó lakosságot. Katarina Bohrer, narra la superviviente judía húngara Katarina Bo- egy túlélő magyar zsidó így meséli el: hrer: „ […] Például, a gimnáziumban egy osztályban csak ”[…] Por ejemplo, en el instituto, en la clase no podía 6-7 zsidó származású diák tanulhatott. Ez volt a haber más de 6 ó 7 estudiantes judíos. -

Argentina Commemorates the International Day in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust Within the Framework of the International

Argentina commemorates the International Day in memory of the victims of the Holocaust Within the framework of the International Day of Commemoration in memory of the victims of the Holocaust – which was settled by the United Nations in 2005 in remembrance of the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 1945- yesterday the national government organized its ceremony, which was attended by members of the national government, authorities of the City of Buenos Aires, survivors and members of different organizations of the Jewish community and the civil society committed with the Holocaust remembrance. The ceremony was organized by the Argentinean Chapter of the IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance), the main international organization dedicated to the research, remembrance and education on the Holocaust. The IHRA is currently integrated by 31 member countries: States of Europe, Israel, United States, Canada and Argentine (which is the only full member of Latin America). The IHRA Local Chapter is formed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Justice and Humans Rights (represented by the Secretary of Humans Rights and Cultural Pluralism) and organizations of the civil society. It has an annual rotating Chairmanship among the Ministries, being in 2016 Chaired by the Secretary of Humans Rights and Cultural Pluralism from the Ministry of Justice and Humans Rights. In this opportunity, the ceremony was held together with the inauguration of the National Monument to honor Holocaust Survivors and also with the inauguration of the “Paseo de los Justos” (The Righteous Square). The Monument consists of a concrete wall composed by 114 cubes with impressions of objects of everyday life, emphasizing the absence of the human being through these marks carved on stone. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection GIORGIO PERLASCA CORRESPONDENCE WITH EVA AND PÁL LANG, 1988‐1997 2016.169.1 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Tel. (202) 479‐9717 e‐mail: [email protected] Descriptive summary Title: Giorgio Perlasca correspondence with Eva and Pál Lang Dates: 1988‐1997 Accession number: 2016.169.1 Creator: Perlasca, Giorgio. Extent: 5 folders Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Abstract: Correspondence, sent between Giorgio Perlasca, of Padua, Italy, and Eva and Pál Lang, of Budapest, Hungary, 1988‐1992. and with Perlasca's family, 1992‐1997. The Langs, who were among the Jews saved by Perlasca's actions in Budapest in 1944‐1945, when Perlasca provided over 5,000 people with safe conduct passes through the Spanish legation in Budapest to prevent their deportation by the Nazis, contacted him in 1988 to express their gratitude. The Langs remained in contact with Perlasca in the following years, visiting him in Italy and hosting visits in Hungary, which are documented in this correspondence. In addition, Perlasca describes Holocaust commemoration events he had been invited to, including his naming as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1988, and his reflections on human rights and anti‐ Semitism in contemporary Europe. Languages: Italian, Hungarian. Administrative Information Access: Collection is open for use, but is stored offsite. Please contact the Reference Desk more than seven days prior to visit in order to request access. -

Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003

Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003 Based on information by the National Focal Points of the RAXEN Information Network Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 – 2003 Based on information by the National Focal Points of the EUMC - RAXEN Information Network EUMC - Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003 2 EUMC – Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 – 2003 Foreword Following concerns from many quarters over what seemed to be a serious increase in acts of antisemitism in some parts of Europe, especially in March/April 2002, the EUMC asked the 15 National Focal Points of its Racism and Xenophobia Network (RAXEN) to direct a special focus on antisemitism in its data collection activities. This comprehensive report is one of the outcomes of that initiative. It represents the first time in the EU that data on antisemitism has been collected systematically, using common guidelines for each Member State. The national reports delivered by the RAXEN network provide an overview of incidents of antisemitism, the political, academic and media reactions to it, information from public opinion polls and attitude surveys, and examples of good practice to combat antisemitism, from information available in the years 2002 – 2003. On receipt of these national reports, the EUMC then asked an independent scholar, Dr Alexander Pollak, to make an evaluation of the quality and availability of this data on antisemitism in each country, and identify problem areas and gaps. The country-by-country information provided by the 15 National Focal Points, and the analysis by Dr Pollak, form Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 of this report respectively. -

TEACHING NIGHT in the SECONDARY CLASSROOM By

TEACHING NIGHT IN THE SECONDARY CLASSROOM by Dyanne K. Loput A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida August 2010 Copyright by Dyanne K. Loput 2010 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express her sincere thanks to Dr. Alan L. Berger for his guidance, encouragement, patience, expertise, and profound brilliance throughout the writing of this manuscript. The author is also grateful to Dr. Miriam Klein Kassenoff for offering the Holocaust Institute, a program that provides educators with a springboard for the knowledge and resources they need to teach Holocaust literature effectively. Additionally, Dr. Barclay Barrios’s and Professor Papatya Bucak’s guidance and inspiration in teaching analytical and creative writing are very much appreciated. iv ABSTRACT Author: Dyanne K. Loput Title: Teaching Night in the Secondary Classroom Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Alan L. Berger Degree: Master of Arts in Teaching English Year: 2010 As a secondary-level educator of literature and writing, I have observed the fundamental need for a sensitive, well-developed curriculum in the art of teaching Eliezer Wiesel’s Night to high school students. This thesis contextualizes Wiesel’s memoir by examining the history of Jewish persecution, the Holocaust itself, and Wiesel’s background. Educational strategies and activities that use both literary analysis and creative writing to engender a comprehensive and thorough realization of the history as expressed through the literature are elucidated. Additionally, several ways in which teachers may lead students to examine the effects, implications, and ramifications of Wiesel’s legacy are supplied. -

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades 7-8 A Study in Character Education A project of the Commissioner’s Task Force on Holocaust Education Authorization for reproduction is hereby granted to the state system of public education. No authorization is granted for distribution or reproduction outside the state system of public education without prior approval in writing. The views of this document do not necessarily represent those of the Florida Department of Education. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Definition of the Term Holocaust ............................................................ 7 Why Teach about the Holocaust............................................................. 8 The Question of Rationale.............................................................. 8 Florida’s Legislature/DOE Required Instruction.............................. 9 Required Instruction 1003.42, F.S.................................................. 9 Developing a Holocaust Unit .................................................................. 9 Interdisciplinary and Integrated Units ..................................................... 11 Suggested Topic Areas for a Course of Study on the Holocaust............ 11 Suggested Learning Activities ................................................................ 12 Eyewitnesses in Your Classroom ........................................................... 12 Discussion Points/Questions for Survivors ............................................. 13 Commonly Asked Questions by Students -

Holocaust Resources with Decscription

Things We Couldn’t Say (Book) - the true story of Diet [pronounced Deet] Eman, a young Dutch woman who, with her fiancé, Hein Sietsma, risked everything to rescue Jews imperiled by Nazi persecution in occupied Holland during World War II. Throughout the years that Diet and Hein aided the Resistance - work that would cost Diet her freedom and Hein his life - their courageous effort ultimately saved the lives of hundreds of Dutch Jews. This book is Diet Eman's account of that tumultuous period. The first-person narrative vividly captures the events of her brave saga - from her initial engagement with Hein in the Resistance operation, to her eventual arrest and imprisonment at the Vught concentration camp, to the final grim toll of the war that devastated all of Europe. Diary entries that Diet and Hein logged during the war as well as excerpts from personal letters that passed between the two young lovers detail their thoughts and emotions during those years. Diet Eman's Things We Couldn't Say is an unforgettable story of heroism, faith, and - above all - love. It is also one of the great Christian stories of the twentieth century - the story of two people whose faith compelled them to stand up to the most sinister evil their generation has ever witnessed. Hidden In Silence (DVD) - Przemysl, Poland, WWII. Germany emerges victorious over the Russians, and the city comes under Nazi control. The Jewish are sent to the ghettos. While some stand silent, Catholic teenager Stefania Podgorska chooses the role of a savior and sneaks 13 Jews into her attic. -

The Holocaust Booklet

• Memories of History • ...to remain silent and“ “indifferent is the greatest sin of all... By Elie Wiesel SPONSORED BY THE KNIGHT FOUNDATION “All that is needed for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” –– Edmund Burke, British statesman Learning from Memories of History ABOUT NEWSPAPER IN EDUCATION Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon emaciated bodies had been flung into shallow graves. The Tallahassee Democrat Newspaper in Wiesenthal wrote, “The new generation has to Education program is one of more than 950 hear what the older generation refuses to tell Eisenhower insisted on seeing everything. newspapers that offer educational activities, it.” Wiesenthal, who died in September 2005, He witnessed sheds piled with bodies, various workshops and guides to parents, teachers devoted his life to documenting the crimes of the torture devices and a butcher’s block used for and students. NIE programs make newspapers Holocaust and to hunting down the perpetrators available free to classrooms. smashing gold fillings from the mouths of the still at large. “When history looks back,” dead. According to the Dwight D. Eisenhower In cooperation with The National Council of Wiesenthal explained, “I want people to know Library Archives, “Eisenhower felt that it was Jewish Women (NCJW), Tallahassee Section, this the Nazis weren’t able to kill millions of people necessary for his troops to see for themselves, complementary teaching tool is attached to many and get away with it.” His work stands as a and the world to know about the conditions at learning strands and has been written and aligned reminder and a warning. -

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27 -

USHMM Finding

RG-46.046M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives Finding Aid RG-46 Bulgaria RG-46.046M Acc. 2004. 112 Title: Papers of Dimitr Iosifov Peshev. Fond 1335, 1894 - 1973. Extent: 1 microfilm reel. Organization and arrangement: Fond 1335 Opis 1. Arrangement is thematic. Provenance: From the Central State Archives of Bulgaria in Sofia, Fond 1135 Opis 1. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives received filmed collection via the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum International Programs Division in April 2004. Restrictions on access: No restrictions on access. Restrictions on use: Restrictions on use apply. Copyright for publication remains with the Bulgarian Archives. Duplication of this material in its entirety for commercial purposes can be made to a third party only with permission of the Bulgarian Archives. Language: Bulgarian. Scope and Content: Selected records from papers of Dimitar Peshev, prominent politician, who played a crucial role in the preventing the deportation of the Bulgarian Jews during the Holocaust. Inventory: Fond 1335. Papers of Dimitr Iosifov Peshev, 1894 - 1973. Opis 1 d. 38 Letter from the Central Consistory to Peshev as Minister of Justice regarding the new law of the implementation of civil marriage. 1936. d. 115 List of Jews who perished in all Bulgarian wars from all Bulgarian areas, 1885, 1912, 1913, 1915 - 1918. 1938. RG-46.046M 1 Papers of Dimitr Iosifov Peshev. Fond 1335. RG-46.046M d. 118 Correspondence from the Jewish Consistory, Bulgarian lawyers, and Bulgarian citizens, regarding the development of legislation for the Defense of the Nation. 1940. d. 119 Informational letter from Filov regarding development of the project of the Defense of the Nation Act. -

9"E7<8.E8 ;<#1#)7 <; );4.7 E;<.41;8 4;.79;<.41;<( ,1(1/<)8.E97&7& 9<;/7

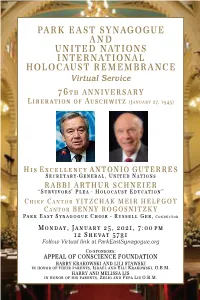

-<9"E7<8.E8 ;<#1#)7 < ; );4.7E;<.41;8 4;.79;<.41;<( ,1(1/<)8.E97&7&9<;/7 Virtual Service B2 <;;4798<9 (?D=CB?A>EAE<6@02?B C>6C=+E!$E ,?@ 70D::D>0+ <;.1;41 #).79978 8D0=DBC=+#D>D=C:$E)>?BD3E;CB?A>@E 9<4E<9.,)9E8/,;7479 86='?'A=@E-:DCEE,A:A0C6@BE7360CB?A> E / , 4 7 / < ; . 1 9 4./,<"E&749E,7(#1. / < ; . 1 9 7;; E91#18;4." -C=E7C@BE8+>C%A%6DE/2A?=EE96@@D::E#D=$ / A > 3 6 0 B A= &A>3C+$EC>6C=+E!$E!!$E *5 !E82D'CBE Follow Virtual link at ParkEastSynagogue.org /A@*A>@A=@ <--7<(E1E/1;8/47;/7E1);<.41; ,<99 E"9<"18"4E<;E(4(4E8.<8"4 ?>E2A>A=EAEB2D?=E*C=D>B@$E4@=CD:EC>3E7::?E"=CA@?$E1& ,<99 E<;E&7(488<E(48 ?>E2A>A=EAE2?@E*C=D>B@$ED:?%EC>3E-D*CE(?@E1& ?=B6C:E8D='?0D Presiding Rabbi Arthur Schneier Senior Rabbi, Park East Synagogue; Founder and President, Appeal of Conscience Foundation Mizmor L’David – The Lord is my Shepherd (Psalm 23) Park East Synagogue Choir; Russell Ger, Conductor Shema Yisrael – Hear ‘O Israel (Keynote Prayer) Etz Chaim – Tree of Life Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Rabbi Arthur Schneier Holocaust Survivor “Survivors Plea - Holocaust Educ ation” His Excellency Antonio Guterres Secretary-General, United Nations Kel Maleh Rachamim – Memorial Prayer Chief Cantor Yitzchak Meir Helfgot Memorial Kaddish Rabbi Arthur Schneier Ani Ma’amin – Prayer of Faith Ose Shalom – A Prayer for Peace Children of the Rabbi Arthur Schneier Park East Day School and Park East Synagogue Nadav, Asaf, Yuval Osterweil, Sophie Gut, Larkin Horowitz and Danielle Rapport Violinist: Yuval Osterweil - Pianist: Sam Nakon 2 Vice President Joseph R.