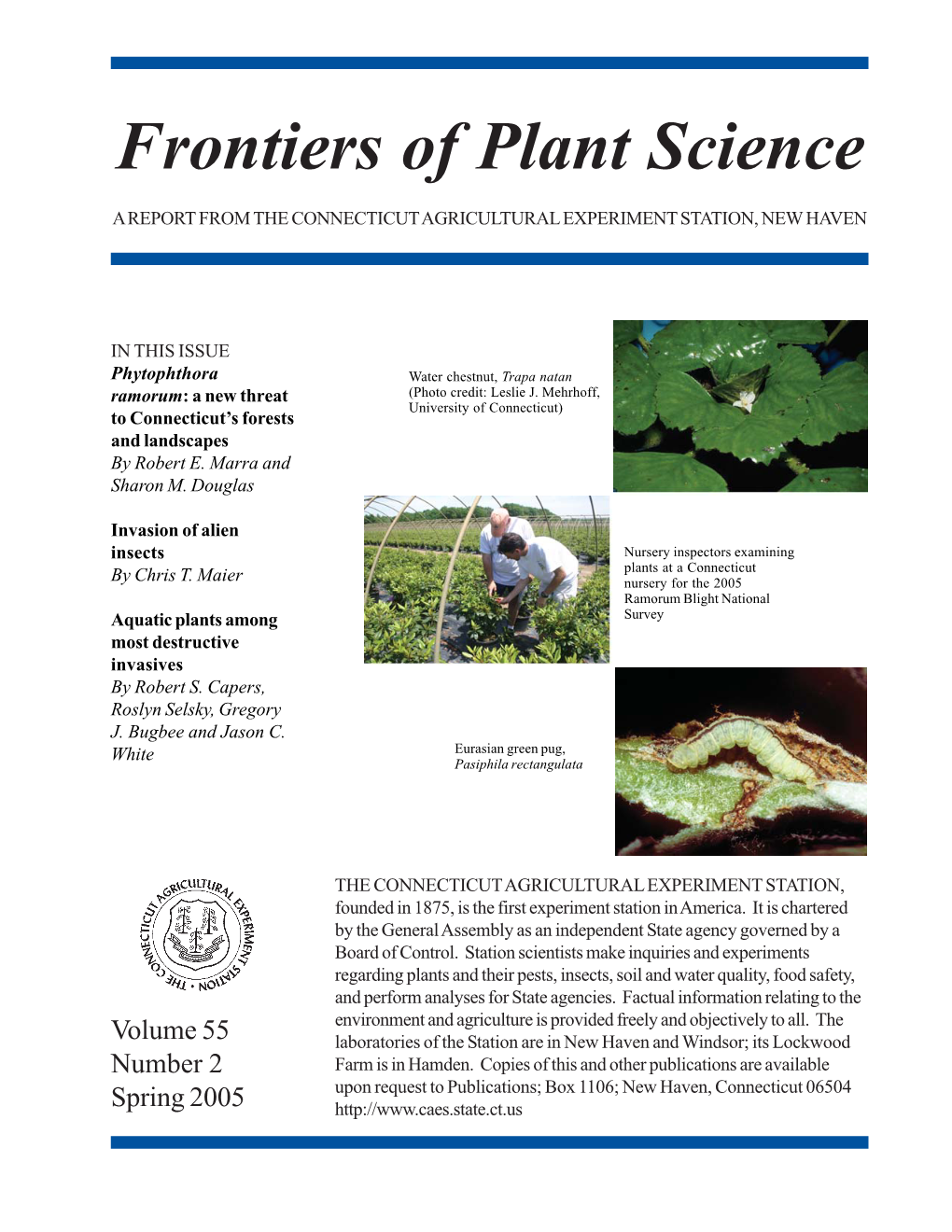

Frontiers of Plant Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Lepidoptera, Ex Cluding Non-Crambine Pyralidae

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 55-172 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: LEPIDOPTERA, EX CLUDING NON-CRAMBINE PYRALIDAE By J. S. Dugdale1 CONTENTS Introduction 55 Acknowledgements 58 Faunal Composition and Relationships 58 Faunal List 59 Key to Families 68 1. Arctiidae 71 2. Carposinidae 73 Coleophoridae 76 Cosmopterygidae 77 3. Crambinae (pt Pyralidae) 77 4. Elachistidae 79 5. Geometridae 89 Hyponomeutidae 115 6. Nepticulidae 115 7. Noctuidae 117 8. Oecophoridae 131 9. Psychidae 137 10. Pterophoridae 145 11. Tineidae... 148 12. Tortricidae 156 References 169 Note 172 Abstract: This paper deals with all Lepidoptera, excluding the non-crambine Pyralidae, of Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Snares Is. The native resident fauna of these islands consists of 42 species of which 21 (50%) are endemic, in 27 genera, of which 3 (11%) are endemic, in 12 families. The endemic fauna is characterised by brachyptery (66%), body size under 10 mm (72%) and concealed, or strictly ground- dwelling larval life. All species can be related to mainland forms; there is a distinctive pre-Pleistocene element as well as some instances of possible Pleistocene introductions, as suggested by the presence of pairs of species, one member of which is endemic but fully winged. A graph and tables are given showing the composition of the fauna, its distribution, habits, and presumed derivations. Host plants or host niches are discussed. An additional 7 species are considered to be non-resident waifs. The taxonomic part includes keys to families (applicable only to the subantarctic fauna), and to genera and species. -

Rules Governing Invasive Species and Noxious Weeds

02.06.09 – RULES GOVERNING INVASIVE SPECIES AND NOXIOUS WEEDS 000. LEGAL AUTHORITY. This chapter is adopted under the legal authority of Sections, 22-1907, 22-2004, 22-2006, 22-2403, and 22-2412, Idaho Code. ( ) 001. TITLE AND SCOPE. 01. Title. The title of this chapter is IDAPA 02.06.09, “Rules Governing Invasive Species and Noxious Weeds.” ( ) 02. Scope. This rule governs the designation of invasive species, inspection, permitting, decontamination, recordkeeping and enforcement and apply to the possession, importation, shipping, transportation, eradication, and control of invasive species. This rule identifies those noxious weeds that have been officially designated by the Director as Noxious Weeds in the state of Idaho, designates articles capable of disseminating noxious weeds, requires treatment of articles to prevent dissemination of noxious weeds and provides authority to designate cooperative weed management areas for management of noxious weeds. Also this rule governs the inspection, certification, and marking of noxious weed free forage and straw to allow for the transportation and use of forage and straw in Idaho and states where regulations and restrictions are placed on such commodities. ( ) 002. -- 109. (RESERVED) SUBCHAPTER A – INVASIVE SPECIES 110. DEFINITIONS. In addition to the definitions found in Section 22-1904 and 22-2005, Idaho Code, the following definitions apply in the interpretation and enforcement of Subchapter A only: ( ) 01. Acts. Title 22, Chapter 19, Idaho Code, the “Idaho Invasive Species Act of 2008” and Title 22, Chapter 20, the “Idaho Plant Pest Act of 2002.” ( ) 02. Aquatic Invertebrate Invasive Species. Those species listed in Section 140. ( ) 03. Control. The abatement, suppression, or containment of an invasive species or pest population. -

Methods and Work Profile

REVIEW OF THE KNOWN AND POTENTIAL BIODIVERSITY IMPACTS OF PHYTOPHTHORA AND THE LIKELY IMPACT ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES JANUARY 2011 Simon Conyers Kate Somerwill Carmel Ramwell John Hughes Ruth Laybourn Naomi Jones Food and Environment Research Agency Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 13 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Objectives .......................................................................................................................... 15 2. Review of the potential impacts on species of higher trophic groups .................... 16 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 Methods ............................................................................................................................. 16 2.3 Results ............................................................................................................................... 17 2.4 Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 44 3. Review of the potential impacts on ecosystem services ....................................... -

E-Acta Natzralia Pannonica

e ● Acta Naturalia Pannonica e–Acta Nat. Pannon. 5: 39–46. (2013) 39 Hungarian Eupitheciini studies (No. 2) Records from Nattán’s collection (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) Imre Fazekas Abstract: Data on 37 species collected in Hungary are given. Additional data on faunistics, taxonomy and zoogeography of cer- tain species are provided by the author, with comments. Figures of the genitalia of some species are included. With 18 figures. Key words: Lepidoptera, Geometridae, Euptheciini, distribution, biology, Hungary. Author’s address: Imre Fazekas, Regiograf Institute, Majális tér 17/A, H-7300 Komló, Hungary. Introduction A detailed account of the Eupitheciini species in 20% KOH solution. Genitalia were cleaned and Hungary has been given in five previous works dehydrated in ethanol and mounted in Euparal (Fazekas 1977ab, 1979ab, 1980, 2012). To date 64 between microscope slides and cover slips. Illus- Hungarian Geometridae, tribus Eupitheciini are trations of adults were produced by a multi-layer known. technique using a Sony DSC HX100V with a 4x Present paper contains faunistical data of the Macro Conversion Lens. The photographs were Eupitheciini specimens in the Nattán collection (in processed by the software Photoshop CS3 version. coll. Janus Pannonius Museum, H-Pécs) that col- The genitalia illustrations were produced in a sim- lected outside of the South Transdanubia. ilar manner with multi-layer technique, using an- Miklós Nattán (1910–1970) was an amateur lep- other digital camera (BMS tCam 3,0 MP) and a idopterist who, over nearly six decades, made one XSP-151-T-LED Microscope with a plan lens 4/0.1 of the most significant private collections of Lepi- and 10/0.25. -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and Evolutionary Correlates of Novel Secondary Sexual Structures

Zootaxa 3729 (1): 001–062 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3729.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CA0C1355-FF3E-4C67-8F48-544B2166AF2A ZOOTAXA 3729 Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures JASON J. DOMBROSKIE1,2,3 & FELIX A. H. SPERLING2 1Cornell University, Comstock Hall, Department of Entomology, Ithaca, NY, USA, 14853-2601. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E9 3Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Brown: 2 Sept. 2013; published: 25 Oct. 2013 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 JASON J. DOMBROSKIE & FELIX A. H. SPERLING Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures (Zootaxa 3729) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2013 ISBN 978-1-77557-288-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-289-3 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2013 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2013 Magnolia Press 2 · Zootaxa 3729 (1) © 2013 Magnolia Press DOMBROSKIE & SPERLING Table of contents Abstract . 3 Material and methods . 6 Results . 18 Discussion . 23 Conclusions . 33 Acknowledgements . 33 Literature cited . 34 APPENDIX 1. 38 APPENDIX 2. 44 Additional References for Appendices 1 & 2 . 49 APPENDIX 3. 51 APPENDIX 4. 52 APPENDIX 5. -

Pests in Northwestern Washington Prompted a 1994-1995 CAPS Survey of Apple Trees to Identify All Leaf-Feeding Apple Pests Currently in Whatcom County

6. Biology / Phenology a. Biology 1. Exotic Fruit Tree Pests in Whatcom County, Washington Eric LaGasa Plant Services Div., Wash. St. Dept. of Agriculture P.O. Box 42560, Olympia, Washington 98504-2560 (360) 902-2063 [email protected] The Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) has conducted detection surveys and other field projects for exotic pests since the mid-1980's, with funding provided by the USDA/ APHIS Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) program. Recent discovery of several exotic fruit tree pests in northwestern Washington prompted a 1994-1995 CAPS survey of apple trees to identify all leaf-feeding apple pests currently in Whatcom County. Additional exotic apple pest species, new to either the region or U.S. were discovered. This paper presents some brief descriptions of species detected in that project, and other exotic fruit tree pest species discovered in northwest Washington since 1985. Table 1. - Exotic Fruit Tree Pests New to Northwestern Washington State - 1985 to 1995 green pug moth - Geometridae: Chloroclystis rectangulata (L.) An early, persistent European pest of apple, pear, cherry and other fruit trees. Larvae attack buds, blossoms, and leaves from March to June. Damage to blossoms causes considerable deformation of fruit. Larvae are common in apple blossoms in Whatcom County, where it was first reared from apple trees in 1994. This pest, new to North America, was also recently detected in the northeastern U.S. Croesia holmiana - Tortricidae: Croesia holmiana (L.) A common pest of many fruit trees and ornamental plants in Europe and Asia, where it is considered a minor problem. Spring larval feeding affects only leaves. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Barrowhill, Otterpool and East Stour River)

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 D (Barrowhill, Otterpool and East Stour River) The tetrad TR13 D is an area of mostly farmland with several small waterways, of which the East Stour River is the most significant, and there are four small lakes (though none are publically-accessible), the most northerly of which is mostly covered with Phragmites. Other features of interest include a belt of trees running across the northern limit of Lympne Old Airfield (in the extreme south edge of the tetrad), part of Harringe Brooks Wood (which has no public access), the disused (Otterpool) quarry workings and the westernmost extent of Folkestone Racecourse and. The northern half of the tetrad is crossed by the major transport links of the M20 and the railway, whilst the old Ashford Road (A20), runs more or less diagonally across. Looking south-west towards Burnbrae from the railway Whilst there are no sites of particular ornithological significance within the area it is not without interest. A variety of farmland birds breed, including Kestrel, Stock Dove, Sky Lark, Chiffchaff, Blackcap, Lesser Whitethroat, Yellowhammer, and possibly Buzzard, Yellow Wagtail and Meadow Pipit. Two rapidly declining species, Turtle Dove and Spotted Flycatcher, also probably bred during the 2007-11 Bird Atlas. The Phragmites at the most northerly lake support breeding Reed Warbler and Reed Bunting. In winter Fieldfare and Redwing may be found in the fields, whilst the streams have attracted Little Egret, Snipe and, Grey Wagtail, with Siskin and occasionally Lesser Redpoll in the alders along the East Stour River. Corn Bunting may be present if winter stubble is left and Red Kite, Peregrine, Merlin and Waxwing have also occurred. -

[email protected]

Import Health Standard Commodity Sub-class: Fresh Fruit/Vegetables Korean pear, Pyrus pyrifolia from the Republic of Korea ISSUED Issued pursuant to Section 22 of the Biosecurity Act 1993 Date Issued: 29 July 1999 1 NEW ZEALAND NATIONAL PLANT PROTECTION ORGANISATION The New Zealand national plant protection organisation is the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and as such, all communication should be addressed to: Chief Plants Officer Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry PO Box 2526 Wellington NEW ZEALAND Fax: 64-4-474 4240 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.maf.govt.nz 2 GENERAL CONDITIONS FOR ALL PLANT PRODUCTS All plants and plant products are PROHIBITED entry into New Zealand, unless an import health standard has been issued in accordance with Section 22 of the Biosecurity Act 1993. Should prohibited plants or plant products be intercepted by the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the importer will be offered the option of reshipment or destruction of the consignment. The national plant protection organisation of the exporting country is requested to inform the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of any change in its address. The national plant protection organisation of the exporting country is required to inform the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of any newly recorded organisms which may infest/infect any commodity approved for export to New Zealand. Pursuant to the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, proposals for the deliberate introduction of new organisms (including genetically modified organisms) as defined by the Act IHS Fresh Fruit/Vegetables. Korean pear, Pyrus pyrifolia from the Republic of Korea (Biosecurity Act 1993) ISSUED: 29 July 1999 Page 1 of 16 should be referred to: Manager, Operations Environment Risk Management Authority PO Box 131 Wellington NEW ZEALAND Also note: In order to meet the Environmental Risk Management Authority's requirements the scientific name (i.e. -

Strawberry Root Weevil and Black Vine Weevil By: Christelle Guédot, UW – Madison Fruit Crop Entomology and Extension

Wisconsin Fruit News Volume 2, Issue 4 – May 26, 2017 In This Issue: General Information General Information: Soil-borne diseases of fruit crops: Soil-borne diseases of fruit crops: Introduction Introduction By: Sara Thomas-Sharma and Patricia McManus page 1 IPM: Monitoring pest populations The soil is a major source of plant pathogens – fungi, nematodes, and bacteria and action thresholds – that cause a variety of diseases in fruit crops (Fig. 1, following page). Soil-borne page 2 diseases can also be ‘disease complexes’, caused by a combination of pathogens and Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic specific soil conditions, and some soil-borne pathogens such as nematodes can update additionally vector viruses. Soil-borne pathogens often have: page 3 • A wide host range, infecting multiple crops Insect Diagnostic Lab update • Ability to survive as non-pathogens in organic debris page 4 • Hardy survival structures (in the soil or on the plant) that can withstand Berry Crops: temperature differences, dry conditions, and long periods without a plant Spotted wing drosophila forecast for 2017 host. page 5 • A preference for specific soil/water conditions (e.g., nematodes prefer sandy Strawberry root weevil and Black soils and Phytophthora prefers waterlogged soils). vine weevil page 5 Symptoms associated with soil-borne diseases can be aboveground and/or belowground. Aboveground symptoms (Fig. 1 A, B) such as wilting, stunting, and Cranberries: Cranberry degree-day map and yellowing are more readily observed, and call attention to an underlying problem. On update the other hand, it is only when infected plants are uprooted (Fig. 1 C, D), that page 7 belowground symptoms such as root/crown rot, discoloration of vascular system, etc. -

Biosecurity Risk Assessment

An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries by Dr Robert C Keogh February 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-007347 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-320-8 ISSN 1440-6845 An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries Publication No. 11/141 Project No. PRJ-007347 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication.