Stewart Geddes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: Interviews complete and in-progress (at January 2019) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed Recording Agreement, agreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and Moving Image catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR PATRICK BOURNE ELISABETH COLLINS IVOR ABRAHAMS DENIS BOWEN MICHAEL COMPTON NORMAN ACKROYD FRANK BOWLING ANGELA CONNER NORMAN ADAMS ALAN BOWNESS MILEIN COSMAN ANNA ADAMS SARAH BOWNESS STEPHEN COX CRAIGIE AITCHISON IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG EDWARD ALLINGTON GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ALEXANDER ANTRIM STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON RASHEED ARAEEN RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ARDIZZONE ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW DIANA ARMFIELD STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE KENNETH ARMITAGE ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE MARIT ASCHAN LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS ROY ASCOTT ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS FRANK AVRAY WILSON JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE GILLIAN AYRES SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES WILLIAM BAILLIE KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY PHYLLIDA BARLOW STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILHELMINA BARNS- CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY GRAHAM NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WENDY BARON ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS -

CV New 2020 Caronpenney (CRAFTSCOUNCIL)

Caron Penney Profile Caron Penney is a master tapestry weaver, who studied at Middlesex University and has worked in textile production for over twenty-five years. Penney creates and exhibits her own artist led tapestries for exhibition and teaches at numerous locations across the UK. Penney is also an artisanal weaver and she has manufactured the work of artists from Tracey Emin to Martin Creed. Employment DATES October 2013 - Present POSITION Freelance Sole Trader BUSINESS NAME Atelier Weftfaced CLIENTS Martin Creed, Gillian Ayres, Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Campaign for Wool, Simon Martin & Pallant House Gallery TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Tapestry DATES 2016, 2017 & 2018 POSITION Special Lecturer EMPLOYER Central Saint Martins, University of Arts London LEVEL BA Hons Textile Design TYPE OF BUSINESS Education DATES January 2014 - July 2015 POSITION Consultant EMPLOYER West Dean Tapestry Studio, W. Sussex, PO18 0QU CLIENTS Basil Beattie, Hayes Gallery, Craft Study Centre for ‘Artists Meets their Makers’ exhibition, Pallant House. TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Tapestry DATES December 2009 - October 2013 POSITION Director EMPLOYER West Dean Tapestry Studio, W. Sussex, PO18 0QU RESPONSIBILITIES The main duties included directing a team of weavers, while creating commissions, curating exhibitions, developing new innovations, assisting with fundraising, and creating a conservation and archiving procedure for the department. CLIENTS Tracey Emin, White Cube Gallery, Martin Creed, Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Historic Scotland. TYPE OF BUSINESS Manufacture of Textiles/Tapestry DATES 2000 - Present POSITION Short Course Tutor EMPLOYERS Fashion and Textiles Museum, Ashmolean Museum, Morley College, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Ditchling Museum , Fleming Collection, Charleston Farmhouse, West Dean College, William Morris Gallery, and many others. -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

Sturm Und Drang : JONAS BURGERT at BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY DAFYDD JONES : JONAS BURGERT at JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN

FREE 16 HOT & COOL ART : JONAS BURGERT AT BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY : JONAS BURGERT AT Sturm und Drang DAFYDD JONES JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN STATE 11 www.state-media.com 1 THE ARCHERS OF LIGHT 8 JAN - 12 FEB 2015 ALBERTO BIASI | WALDEMAR CORDEIRO | CARLOS CRUZ-DÍEZ | ALMIR MAVIGNIER FRANÇOIS MORELLET | TURI SIMETI | LUIS TOMASELLO | NANDA VIGO Luis Tomasello (b. 1915 La Plata, Argentina - d. 2014 Paris, France) Atmosphère chromoplastique N.1016, 2012, Acrylic on wood, 50 x 50 x 7 cm, 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 x 2 3/4 inches THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING: 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ CAREL VISSER, 18 FEB - 10 APR 2015 TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com JAN_AD(STATE).indd 1 03/12/2014 10:44 WiderbergAd.State3.awk.indd 1 09/12/2014 13:19 rosenfeld porcini 6th febraury - 21st march 2015 Ali BAnisAdr 11 February – 21 March 2015 4 Hanover Square London, W1S 1BP Monday – Friday: 10.00 – 18.00 Saturday: 10.00 – 17.0 0 www.blainsouthern.com +44 (0)207 493 4492 >> DIARY NOTES COVER IMAGE ALL THE FUN OF THE FAIR IT IS A FACT that the creeping stereotyped by the Wall Street hedge-fund supremo or Dafydd Jones dominance of the art fair in media tycoon, is time-poor and no scholar of art history Jonas Burgert, 2014 the business of trading art and outside of auction records. The art fair is essentially a Photographed at Blain|Southern artists is becoming a hot issue. -

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Dennis, M. Submitted version deposited in Coventry University’s Institutional Repository Original citation: Dennis, M. () Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979. Unpublished MSC by Research Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to Third Party Copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Mark Dennis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy/Master of Research September 2016 Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement Title: Forename: Family Name: Mark Dennis Student ID: Faculty: Award: 4744519 Arts & Humanities PhD Thesis Title: Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Freedom of Information: Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) ensures access to any information held by Coventry University, including theses, unless an exception or exceptional circumstances apply. In the interest of scholarship, theses of the University are normally made freely available online in the Institutions Repository, immediately on deposit. -

Peter Lanyon's Biography

First Crypt Group installation, 1946 Lanyon by Charles Gimpel Studio exterior, Little Park Owles c. 1955 Rosewall in progress 1960 Working on the study for the Liverpool mural 1960 On Porthchapel beach, Cornwall PETER Lanyon Peter Lanyon Zennor 1936 Oil on canvas November: Awarded second prize in John Sheila Lanyon Moores Exhibition, Liverpool for Offshore. Exterior, Attic Studio, St Ives February: Solo exhibition, Catherine Viviano Records slide lecture for British Council. February: Resigns from committee of Penwith Gallery, New York. Included in Sam Hunter’s European Painting Wartime, Middle East, 1942–3 Society. January: One of Three British Painters at and Sculpture Today, Minneapolis Institute of January: Solo exhibition, Fore Street Gallery, Passedoit Gallery, New York. Later, Motherwell throws a party for PL who Art and tour. St Ives. Construction 1941 March: Demobilised from RAF and returns Spring: ‘The Face of Penwith’ article, Cornish meets Mark Rothko and many other New At Little Park Owles late 1950s April: Travels to Provence where he visits Aix March –July: Stationed in Burg el Arab, fifty to St Ives. Review, no 4. January–April: Italian government scholarship York artists. Visiting Lecturer at Falmouth College of Art January: Solo exhibition, Catherine Viviano March–April: Visiting painter, San Antonio and paints Le Mont Ste Victoire. miles west of Alexandria. March: Exhibits in Danish, British and – spends two weeks in Rome and rents and West of England College, Bristol. Gallery, New York. Art Institute, Texas, during which time he April: Marries Sheila Browne. 6 February: Among the ‘moderns’ who March: Exhibits in London–Paris at the ICA, American Abstract Artists at Riverside studio at Anticoli Corrado in the Abruzzi June: Joins Perranporth gliding club. -

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

Jack Tworkov: Becoming Himself

Jack Tworkov: Becoming Himself By Carter Ratcliff, May 2017 Jack Tworkov developed an acclaimed Abstract Expressionist style and then left it behind, seeking to transcend style and achieve true selfexpression through painting. In 1958, the Museum of Modern Art in New York launched one of its most influential exhibitions. Titled “The New American Painting,” it sent works by leading Abstract Expressionists on a tour of eight European cities. Responses were varied. Some Old World critics saw canvases by Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, and their colleagues as unnecessarily large and aesthetically naïve. Others acknowledged, with differing degrees of reluctance, that the unfamiliar imagery confronting them was genuinely innovative. A critic in Berlin praised Jack Jack Tworkov, X on Circle in the Square (Q4-81 #2), Tworkov for dispensing 1981, acrylic on canvas, 49 x 45 in.; Courtesy Alexander with ready-made premises Gray Associates, New York © Estate of Jack Tworkov / and assumptions, seeing the Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY world afresh, and painting what is “real.” “The New American Painting” advanced an ambitious hypothesis: the Abstract Expressionists now formed the modernist vanguard. Convinced that they were no less significant than Impressionists or Cubists, the painters themselves had come to this conclusion a decade earlier. No longer American provincials, they had merged personal ambition with historical destiny. with historical destiny. Understandably, then, when an Abstract Expressionist achieved a mature style he—or she, in the cases of Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell—tended to stay with it. Of course, signature styles evolved over the years. Mark Rothko’s imagery grew darker. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture. -

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge

Generation Painting: Abstraction and British Art, 1955–65 Saturday 5 March 2016, 09:45-17:00 Howard Lecture Theatre, Downing College, Cambridge 09:15-09:40 Registration and coffee 09:45 Welcome 10:00-11:20 Session 1 – Chaired by Dr Alyce Mahon (Trinity College, Cambridge) Crossing the Border and Closing the Gap: Abstraction and Pop Prof Martin Hammer (University of Kent) Fellow Persians: Bridget Riley and Ad Reinhardt Moran Sheleg (University College London) Tailspin: Smith’s Specific Objects Dr Jo Applin (University of York) 11:20-11:40 Coffee 11:40-13:00 Session 2 – Chaired by Dr Jennifer Powell (Kettle’s Yard) Abstraction between America and the Borders: William Johnstone’s Landscape Painting Dr Beth Williamson (Independent) The Valid Image: Frank Avray Wilson and the Biennial Salon of Commonwealth Abstract Art Dr Simon Pierse (Aberystwyth University) “Unity in Diversity”: New Vision Centre and the Commonwealth Maryam Ohadi-Hamadani (University of Texas at Austin) 13:00-14:00 Lunch and poster session 14:00-15:20 Session 3 – Chaired by Dr James Fox (Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge) In the Thick of It: Auerbach, Kossoff and the Landscape of Postwar Painting Lee Hallman (The Graduate Center, CUNY) Sculpture into Painting: John Hoyland and New Shape Sculpture in the Early 1960s Sam Cornish (The John Hoyland Estate) Painting as a Citational Practice in the 1960s and After Dr Catherine Spencer (University of St Andrews) 15:20-15:50 Tea break 15:50-17:00 Keynote paper and discussion Two Cultures? Patrick Heron, Lawrence Alloway and a Contested -

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS' LIVES Terry Frost Interviewed By

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Terry Frost Interviewed by Tamsyn Woollcombe C466/22 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/22 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Frost Title: Sir Interviewee’s forename: Terry Sex: Male Occupation: Artist Dates: 1915 - 2003 Dates of recording: 1994.11.19, 1994.11.20, 1994.11.21, 1994.11.22, 1994.12.18 Location of interview: Interviewee’s studio and home Name of interviewer: Tamsyn Woollcombe Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Recording format: D60 Cassette F numbers of playback cassettes: F4312- F4622 Total no. -

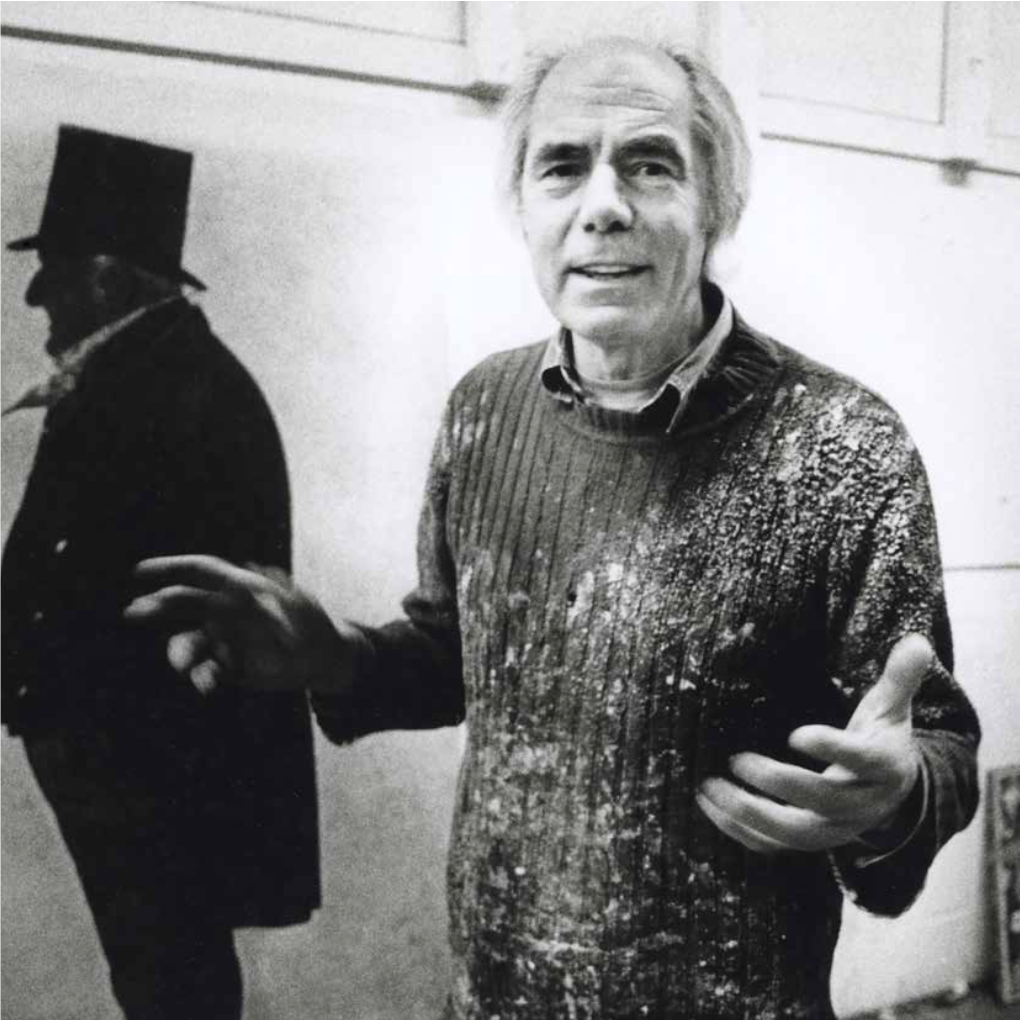

Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES ARTISTS’ LIVES Michael Kidner Interviewed by Penelope Curtis & Cathy Courtney C466/40 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] This transcript is accessible via the British Library’s Archival Sound Recordings website. Visit http://sounds.bl.uk for further information about the interview. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT Access to this interview and transcript is for private research only. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ( [email protected] ) © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C466/40/01-08 Digitised from cassette originals Collection title: Artists’ Lives Interviewee’s surname: Kidner Title: Interviewee’s forename: Michael Sex: Male Occupation: Dates: 1917 Dates of recording: 16.3.1996, 29.3.1996, 4.8.1996 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home Name of interviewer: Penelope Curtis and Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 and two lapel mics Recording format: TDK C60 Cassettes F numbers of playback cassettes: F5079-F5085, F5449 Total no.