A Masterpiece Born of Saint Anthony's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isenheim Altarpiece Restoration Finally Back on Track After Public Outcry

AiA Art News-service Isenheim Altarpiece restoration finally back on track after public outcry More than 30 conservators will treat paintings and sculptures, seven years after French culture ministry halted reckless cleaning of two panels VINCENT NOCE 7th November 2018 10:45 GMT The painted panels will be restored at Colmar’s Unterlinden Museum Photo: Ruedi Walti; © Musée Unterlinden Seven years after halting an unorthodox restoration of the Isenheim Altarpiece, French conservators have resumed work on the celebrated northern Renaissance polyptych in the hope of getting it right this time. It took only six days in 2011 for two restorers with a cloth to strip the varnish off a painted panel depicting the Temptation of Saint Anthony and to revarnish it. They then started to repeat the process on half of Saint Anthony Visiting Saint Paul. Launched before a major expansion of the Unterlinden Museum in the Alsatian region of Colmar, where the altarpiece is housed, the work was not preceded by a scientific examination. When the online magazine La Tribune de l’Art and the newspaper Libération expressed alarm at the speed of the intervention, the ensuing indignation prompted France’s culture ministry to step in and halt the pair. A study that began in 2013 concluded that no real damage had been done to the 1512-16 painting, regarded as the masterpiece of the German artist Mathis Gothart-Nithart, called Matthias Grünewald by art historians. It was a close call, nonetheless. The varnish had been left almost untouched in the darker parts but wiped off in the clearer sections. -

Art in the Stages of Suffering and Death Joanna Aramini College of the Holy Cross, [email protected]

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Visual Arts Department Student Scholarship Visual Arts Department 12-15-2018 Art in the Stages of Suffering and Death Joanna Aramini College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/ visual_arts_student_scholarship Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Art Therapy Commons, and the Pain Management Commons Recommended Citation Aramini, Joanna, "Art in the Stages of Suffering and Death" (2018). Visual Arts Department Student Scholarship. 1. https://crossworks.holycross.edu/visual_arts_student_scholarship/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Visual Arts Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visual Arts Department Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. Art in the Stages of Suffering and Death Joanna Aramini December 15, 2018 Abstract: There has always been a strong link between art and the study of science and medicine, and one of the most iconic images of suffering and death in history to date is Christ suffering on the cross. In this thesis, I examine if and how art can make it possible to transcend human pain and overcome suffering, especially in our modern society where pain is seen as something we cannot deal with, and where we look to medicine and prescriptions to diminish it. I argue that art in the states of suffering and death, closely examining Michelangelo’s La Pieta and Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, can provide a model as a response to pain. For all their differences in composition and artistic style, Michelangelo and Grunewald’s works of art encourage their viewers to focus on pain as a distinctly human experience, in which hope and peace can be found. -

The Word Made Visible in the Painted Image

The Word made Visible in the Painted Image The Word made Visible in the Painted Image: Perspective, Proportion, Witness and Threshold in Italian Renaissance Painting By Stephen Miller The Word made Visible in the Painted Image: Perspective, Proportion, Witness and Threshold in Italian Renaissance Painting By Stephen Miller This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Stephen Miller All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8542-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8542-3 For Paula, Lucy and Eddie CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 Setting the Scene The Rise of Humanism and the Italian Renaissance Changing Style and Attitudes of Patronage in a Devotional Context The Emergence of the Altarpiece in -

DX225792.Pdf

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Olivier Messiaen and the culture of modernity Sholl, Robert The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 Olivier Messiaen and the Culture of Modernity Robert Peter Sholl Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of King's College, University of London, for the degree of PhD. 2003 BL UNW. Robert Sholl Précis Olivier Messiaen and the Culture of Modernity This study interprets the French composer Olivier Messiaen as a religious modernist with a view to revealing a new critical perspective on the origin, style and poetics of his music and its importance in the twentieth century. -

Studies in Late Medieval Wall Paintings, Manuscript Illuminations, and Texts, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-47476-2 BIBLIOGRAPHY

CODA PARTICIPATING IN SYMBOLS OF DEATH Like Nicholas Love’s Mirror, The Somonyng of Everyman is adapted from a Continental text, in this case from the Dutch Elckerlijc. As reading matter designed to appeal to the merchant and artisan classes in an urban setting, Everyman invokes neither pastoral nor monastic contemplation but rather invites participation through an imaginative confrontation with Death and subsequent pilgrimage leading to entry into the grave. The study of Everyman in terms of participation in the symbols of death and dying can serve as an appropriate capstone to the present volume, hence originally intended to be a final chapter. The essay can be accessed at https://works.bepress.com/clifford_davidson/265. © The Author(s) 2017 111 C. Davidson, Studies in Late Medieval Wall Paintings, Manuscript Illuminations, and Texts, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-47476-2 BIBLIOGRAPHY Alexander, Jennifer. “Coventry Holy Trinity Wall Painting.” EDAM Newsletter 11 no. 2 (1989): 37. Alkerton, Richard. [Easter Week sermon, 1406.] British Library, Add. MS. 37677. Allen, Hope Emily, ed. English Writings of Richard Rolle. 1931; reprint, Oxford: Clarendon (1963). ——— and Sanford Brown Meech, eds. The Book of Margery Kempe. EETS, o.s. 212. London: Oxford University Press (1940). Anderson, M. D. The Imagery of British Churches. London: John Murray (1955). Arbismann, Rudolph. “The Concept of ‘Christus Medicus’ in St. Augustine.” Traditio 10 (1954): 1–28. Ashley, Kathleen, and Pamela Sheingorn. Interpreting Cultural Symbols: Sainte Anne in Late Medieval Society. Athens: University of Georgia Press (1990). Aston, Margaret. England’s Iconoclasts I: Laws Against Images. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1988). Augustine of Hippo, St. -

WIT 2002 Round 6

WIT 2002 Round 6 Seth Teitler, Larissa Kelly, Jeff Kelly October 22, 2002 1 Tossups The transmembrane conductance regulator, a molecule that transports sodium chloride in and out of cells, malfunctions as a result of a defective gene on chromosome seven. Symptoms can include liver disease, which causes five percent of deaths, poor functioning of the pancreas, and increased suscepti- bility to Pseudomonas, Hemophilus, and Streptococcus bacteria. FTP, name this fatal genetic disease whose most prominent symptom is a buildup of mu- cus in the lungs. Answer: cystic fibrosis Their language, now almost extinct, is a member of the Tungus branch of the Altaic family. Early records describe them as the I-lou, a group of fishers, hunters, and gatherers, or as the Tung-ihu, “eastern barbarians.” In the 12th century a group of them known as the Jurchen drove the Sung out of northeastern China, where they established a dynasty that was soon destroyed by the Mongols. They forced the Chinese to adopt their tribal custom of braiding their hair into pigtails when in 1644. FTP–name this ethnicgroup drove out the Ming to establish the Qing dynasty. Answer: Manchu One of his forms is the wind-god Ehecatl [eh-heh-CAHTULL], and his twin brother Xolotl [pron. show-LOW-tull] guides the dead down to Mict- 1 lan. He presided over the fifth sun, and was identified with the Mayan god Kukulcan [coo-cool-CAHN]. A son of the goddess Coatlicue [coh-AT- lih-cue], he was driven out by his rival Tezcatlipoca [tez-cat-lih-POH-cah], but promised he would return. -

Worthy Is the Lamb: Pastoral Symbols of Salvation in Christian Art and Music

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-22-2004 Worthy is the Lamb: Pastoral Symbols of Salvation in Christian Art and Music Jo W. Harney Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Harney, Jo W., "Worthy is the Lamb: Pastoral Symbols of Salvation in Christian Art and Music" (2004). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 33. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/33 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worthy is the Lamb: Pastoral Symbols of Salvation in Christian Art and Music By Jo W. Harney Final project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Skidmore College April 2004 Dr. Tom Davis and Dr. Penny Jolly, Advisors Table of Contents List of Illustrations .... .... ... ... ........ ... .... ... .... ...... ... .... .... ... ... .... .. .... ... .. .. ....... ... ... ....... ... ........ 2 Abstract. ............................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter I: Introduction ....... ....... ...... .... .......... ... .... ... ... .... ...... ..... ... ... ... ...... ... .... ... ... .... ... 4 Chapter II: The Shepherd and Sheep -

The Protestant Reformation Revolutionized Art

The Protestant Reformation Revolutionized Art Martin Luther's Reformation ended a period of dominance and unity in Europe under the Roman Catholic Church. This unity lasted for more than 1,000 years. The Protestant reformers influenced artists who became inspired by the new ideas of faith, forgiveness, a personal relationship with God through Jesus Christ, and the powerful stories in the Holy Bible. Isenheim Altarpiece: The Resurrection, (Matthias Grunewald, 1512) This painting illustrates the Ascension and Resurrection as one event with Christ emerging from the tomb and ascending into Heaven bathed in light. Grunewald may have painted three soldiers to remind us of the three wise men. The contrast of light and dark colors enhances the drama of this historic event on the victory of life over death. The soldiers have fallen and their swords have no power. A stunning "world cup" defeat! Think of the impact of this masterpiece of art as a means for teaching people in the troubled world of the 16th century that Jesus Christ has power over armed soldiers, personal conflicts, and death. One can see how Mathias Grunewald thinks deeply about spiritual things and his faith. He cannot read the Holy Bible in his own language (yet) and he understands the importance of the mystery of faith and the Resurrection clearly in his heart, mind, and eyes. The paintings on the Isenheim altar suggest that common people understood God and Jesus Christ in a very personal way before Luther's posting of the 95 Theses and debates with the clergy. I wonder what the ordinary merchant or farmer thought as they viewed these illustrations of the birth of Jesus, John the Baptist, crucifixion, and resurrection. -

Opening: the Isenheim Altarpiece Or “The Taking on Board of Suffering”

Opening: The Isenheim Altarpiece or “The Taking on Board of Suffering” Perhaps one has never suffered, or at least never understood what it is to suffer, unless one has confronted the Christ of the Isenheim altarpiece (1512–16), now in the Unterlinden Museum, Colmar, Alsace (Figure 1). Not that this polyptych altarpiece—or for that matter The Guide to Gethsemane— aims to justify suffering. Rather, it is that Christ the man is held there on the cross in a “suffering,” or in a “pure suffering taken on board” [pâtir pur], to which we shall all be exposed at some time, and from which none of us can fully draw back.1 The ordeal of suffering, from sickness to death, grips humankind, as Emmanuel Levinas says, in an “impossibility of retreat.”2 There are no exemptions; and if we try to claim exemption we risk lying to ourselves about the burden of what is purely and simply our humanity. There are agonies that challenge us to the very limits, that make us see the seriousness of our own decease, even if we share a belief that only God can give us, that we are subsequently to be raised from the dead. A book or a body of work, like life itself, always has to start with some “suffering,” or in any event one has to take on board “suffering” it. Chris- tian ity, which was falsely satisfied with the illusion of purification through suffering, now nourishes itself with a respectable attempt at conciliation (irenicism). In general, it prefers the won der of the newly born to the con- vulsions of someone about to depart this life or the rapture of revelation to the numb stupor caused by a death. -

The Isenheim Alterpiece

Good Friday reflection by Andrew McCully! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! THE ISENHEIM ALTERPIECE ! One of the many things that I love about so much Christian art is that it so often shares universal significance with a focus on a specific place and specific worshipers. The mysterious German painter Grunewald, painted this extraordinary crucifixion as part of a large and folding altarpiece for the Anthonine canons of Isenheim in Alsace. The altarpiece, broken up when religious orders were suppressed during the French Revolution, is now in a beautiful museum in Colmar, near Strasbourg, which Nicholas and I visited a couple of years ago. The Anthonines sheltered pilgrims and nursed lepers and victims of plague; but above all they specialized, as they did in their hospital at Isenheim, in the treatment of St Anthony’s Fire. This was the name given to the dreadful condition caused (as we now know, but was not understood at the time) by the ergot fungus which attacks rye. In times of famine, mouldy rye would be milled into flour along with the healthy grain, contaminating the bread eaten by poor people. The result was epidemics in Northern Europe, in which the skin of those affected itched and burned, then turned black and gangrenous. The bishop of Lincoln’s chaplain, passing through the region in 1200 has this terrifying description of sufferers: “Their flesh was partly burnt, the bones charred and certain limbs had fallen off and, despite these mutilations, their half-preserved bodies appeared to be in rude health.” All this was naturally accompanied by excruciating pain and frequently by hallucinations caused by the fungus. -

Disease and the Diabolical in Grünewald's Temptation of St

Touch of Evil: Disease and the Diabolical in Grünewald’s Temptation of St. Anthony Jerry Marino From the ninth century to as recent as the 1950s, a mysterious Differing from St. Roch, who was believed to have suffered illness swept periodically through Northern Europe, ravaging from Bubonic plague and survived, or from St. Sebastian, entire villages and afflicting both population and livestock.1 whose arrow-pierced body came to represent transcendence Eye-witness accounts, sometimes horrific in detail, described over infectious disease, St. Anthony did not initially have the the devastation and posited a variety of infernal names for makings of a plague saint.6 However, throughout much of the ailment: ignis sacer (holy fire), ignis infernalis (hell fire), late-medieval France and Germany, his legend was reinter- and ignis occultus (hidden fire).2 Outbreaks of this fiery illness preted and his image was refashioned into that of a plague were especially virulent in the late fifteenth century, such as saint.7 He was invested with the power both to cure and to those documented in Strasbourg in 1466 and in Augsburg in inflict his eponymous disease upon humanity, at will.8 He 1488.3 Contemporary accounts make repeated mention of was also included among the pantheon of plague saints, the now familiar ignis sacer, in addition to two other names often appearing in altarpieces alongside St. Sebastian as co- of relatively later coinage, mal des ardents (the burning illness) intercessor for the afflicted.9 Finally, and most essential to his and feu de Saint Antoine (Saint Anthony’s Fire).4 meteoric fame among the sick and dying, he was appointed The latter term has long been a conundrum since St. -

A Masterpiece Born of Saint Anthony's

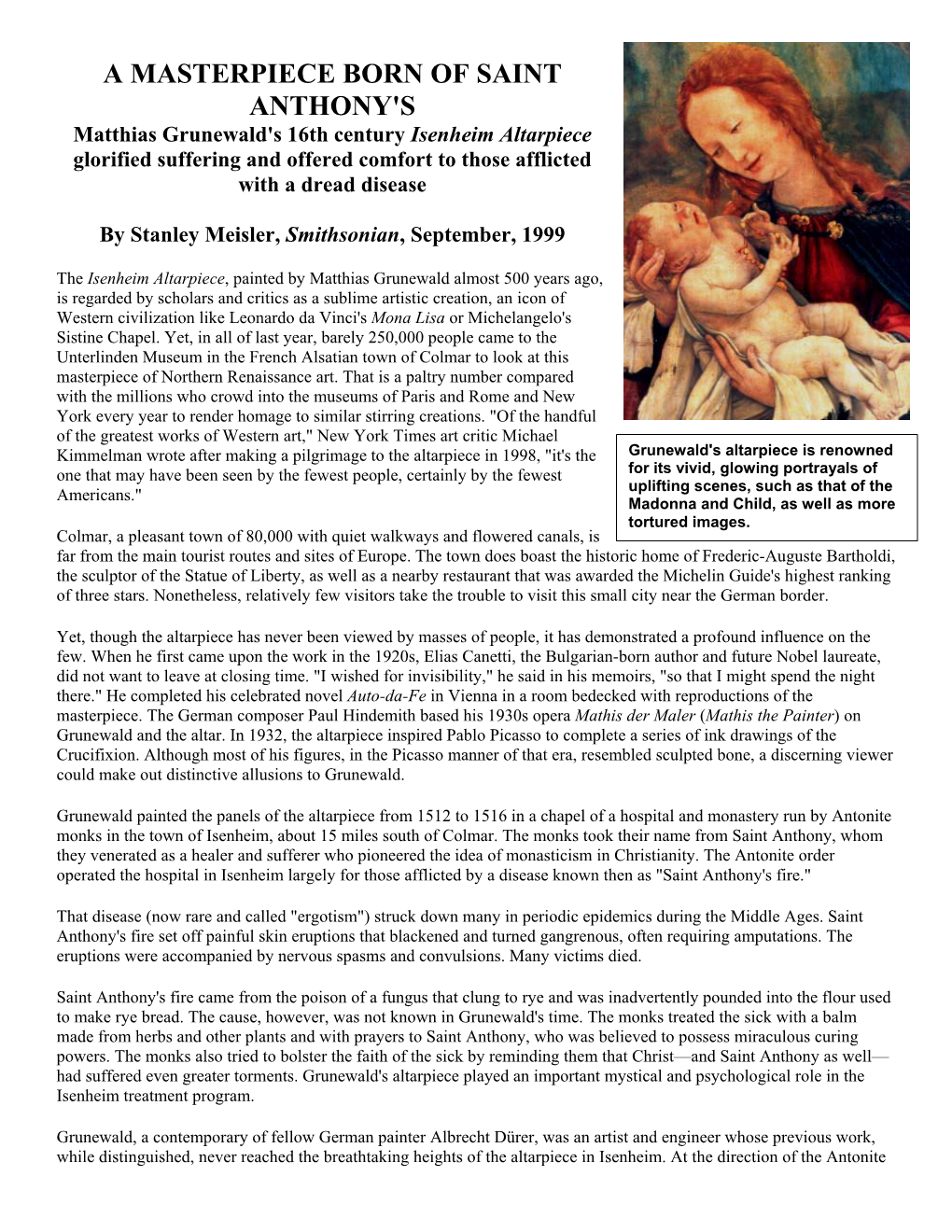

A MASTERPIECE BORN OF SAINT ANTHONY'S Matthias Grunewald's 16th century Isenheim Altarpiece glorified suffering and offered comfort to those afflicted with a dread disease By Stanley Meisler, Smithsonian, September, 1999 The Isenheim Altarpiece, painted by Matthias Grunewald almost 500 years ago, is regarded by scholars and critics as a sublime artistic creation, an icon of Western civilization like Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa or Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. Yet, in all of last year, barely 250,000 people came to the Unterlinden Museum in the French Alsatian town of Colmar to look at this masterpiece of Northern Renaissance art. That is a paltry number compared with the millions who crowd into the museums of Paris and Rome and New York every year to render homage to similar stirring creations. "Of the handful of the greatest works of Western art," New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman wrote after making a pilgrimage to the altarpiece in 1998, "it's the Grunewald's altarpiece is renowned one that may have been seen by the fewest people, certainly by the fewest for its vivid, glowing portrayals of uplifting scenes, such as that of the Americans." Madonna and Child, as well as more tortured images. Colmar, a pleasant town of 80,000 with quiet walkways and flowered canals, is far from the main tourist routes and sites of Europe. The town does boast the historic home of Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi, the sculptor of the Statue of Liberty, as well as a nearby restaurant that was awarded the Michelin Guide's highest ranking of three stars.