Isenheim Altarpiece AHIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BULLETIN IS Jan

ST. ELIJAH ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN CHURCH 15000 N. May, Oklahoma City, OK 73134 Church Office: 755-7804 Church Website: www.stelijahokc.com Church Email: [email protected] JANUARY 17, 2021 Issue 33 Number 3 Venerable and God-bearing Father Anthony the Great & TwelFth Sunday oF Luke; Saints of the Day: Anthony the New, the ascetic of Berrea in Macedonia; New-Martyr George of Ionnina DIRECTORY WELCOME V. Rev. Fr. John Salem Parish Priest 410-9399 We welcome all our visitors. It is an honor to have you worshipping with us. You may find the worship of the Rev. Fr. Elias Khouri Ancient Church very different. We welcome your questions. Assistant Priest 640-3016 Please join us for our Reception held in the Church Hall V. Rev. Fr. Constantine Nasr immediately following the Divine Liturgy. Emeritus We understand Holy Communion to be an act of our unity in Rev. Dn. Ezra Ham faith. While we work toward the unity of all Christians, it Administrator 602-9914 regrettably does not now exist. Therefore, only baptized Rev. Fr. Ambrose Perry Orthodox Christians (who have properly prepared) are Attached permitted to participate in Holy Communion. However, everyone is welcome to partake of the blessed bread that is Anthony Ruggerio 847-721-5192 distributed at the end of the service. We look forward to Youth Director meeting you during the Reception that follows the service. Mom’s Day Out & Pre-K NEW ORTHROS & LITURGY BOOK Sara Cortez – Director 639-2679 • Orthros: p. 4 Email: [email protected] Facebook: “St Elijah Mom’s Day Out” • The Divine Liturgy p. -

Bulgakov Handbook

October 21 G.† Our Ven. Father Hilarion the Great He was born in Palestine, near Gaza City, studied the sciences and was baptized in Alexandria. When he was 15 years old, Hilarion heard about Ven. Anthony the Great and admiring "Anthony's spiritually divine, virtuous way of life" went to him. Having returned home with a blessing from Ven. Anthony, Hilarion found that his parents died and, "despising all worldly pleasures", distributed all his remaining inherited estate to the poor and in a certain deserted place was devoted entirely to prayer and abstinence. St. Hilarion struggled a lot with unclean thoughts, who confused his mind and inflamed his body; but he exhausted his body with work and drove away these thoughts by prayer and meditation on God. The holy hermit suffered much from demons and more than once while standing in prayer heard the crying of children, sobbing of women, roaring of lions and other wild animals, awful noises and confusion presented by the demons. But he did not fear the "demonic traps" and through fervent prayer conquered the "gloomy enemy powers". Once, robbers set upon the holy ascetic, but he by the power of his word convinced them to leave their vice and to lead a good life. Soon all of Palestine heard about the holy hermit's life and many began to come to him for healing of body and soul, but others wished to save their soul under his direction. With his blessing many monasteries were built in Palestine, and going from one monastery to another, he established a strict ascetic paradigm of life in them, having become the same kind of trainer for those seeking salvation in Palestine as Ven. -

Mediterranean Festival—2018

1 The Messenger October 2018 Vol. 31 Issue 10 Mediterranean Festival—2018 2 Orthodox Trivia Quiz 1. Who is the 1st Christian martyr? 7. As Orthodox Christians, we believe “God is the a. Peter b. Stephen Trinity: three ________, one God.” c. David d. Mary Magdalene a. Spirits b. Persons c. Gods d. Angels 2. When did Christianity become legal in the Roman Empire? 8. Which prophet is commonly ascribed as the a. 33 AD b. 70 AD author of the Book of Psalms from the Old Testament? c. 313 AD d. 1054 AD a. David b. Solomon c. Moses d. Abraham 3. Who is referred to as the “new Adam” in some liturgical texts within the Orthodox Church? a. John the Baptist 9. Which city is NOT considered to be one of the b. Jesus Christ first five patriarchates (important centers) of c. Emperor Constantine the Great Christianity? d. Prophet Moses a. Rome b. Bethlehem c. Jerusalem d. Alexandria 4. Who is the first called of the 12 Apostles of Christ? 10. What Great Feast in the Life of the Church is a. Peter c. Matthew celebrated on November 21st (New Calendar)? c. Andrew d. Judas a. Transfiguration of our Lord b. Entrance of our Lord into the Temple 5. What was Peter’s occupation before becoming c. Nativity of the Theotokos a “follower of Christ?” d. Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple a. tent-maker b. carpenter c. farmer d. fisherman 6. Why do Orthodox Christians gather on Sundays to worship during Liturgy and celebrate the Eucharist OR what do we commemorate every Sunday throughout the year? a. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 10, Issue 02, 2021: 28-50 Article Received: 02-02-2021 Accepted: 22-02-2021 Available Online: 28-02-2021 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: https://doi.org/10.18533/jah.v10i2.2053 The Enthroned Virgin and Child with Six Saints from Santo Stefano Castle, Apulia, Italy Dr. Patrice Foutakis1 ABSTRACT A seven-panel work entitled The Monopoli Altarpiece is displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. It is considered to be a Cretan-Venetian creation from the early fifteenth century. This article discusses the accounts of what has been written on this topic, and endeavors to bring field-changing evidence about its stylistic and iconographic aspects, the date, the artists who created it, the place it originally came from, and the person who had the idea of mounting an altarpiece. To do so, a comparative study on Byzantine and early-Renaissance painting is carried out, along with more attention paid to the history of Santo Stefano castle. As a result, it appears that the artist of the central panel comes from the Mystras painting school between 1360 and 1380, the author of the other six panels is Lorenzo Veneziano around 1360, and the altarpiece was not a single commission, but the mounting of panels coming from separate artworks. The officer Frà Domenico d’Alemagna, commander of Santo Stefano castle, had the idea of mounting different paintings into a seven-panel altarpiece between 1390 and 1410. The aim is to shed more light on a piece of art which stands as a witness from the twilight of the Middle Ages and the dawn of Renaissance; as a messenger from the Catholic and Orthodox pictorial traditions and collaboration; finally as a fosterer of the triple Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance expression. -

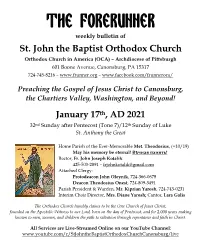

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Church

St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Church Metropolitan JOSEPH, Archbishop A parish of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America Bishop BASIL of Wichita Church Office Tuesday-Friday: 9:00am - 4:00pm Office is Closed on Mondays (281) 251-6000 [email protected] www.StAnthonyTheGreat.org WELCOME TO OUR VISITORS & GUESTS It is a joy to have you with us this morning! Please feel free to complete the Welcome Card or sign the Guest Book in the narthex. Thank you for worshipping with us! RECEIVING COMMUNION While the Orthodox Church continues to pray for the unity of all, Holy Communion is only served to Orthodox Christians who have prepared themselves through prayer, fasting and confession. ELECTRONIC DEVICES Upon entering the church, we ask that you silence your cell phone and refrain from using electronic devices during the service. PRAYER REQUESTS To be included on the prayer list, or to join the parish prayer chain, please contact the church office at [email protected]. TODAY’S ANNOUNCEMENTS ~ August 23, 2020 BREAD OF OBLATION is offered by Vasiliki Domati. SCHEDULE OF THIS WEEK’S DIVINE SERVICES Saturday, August 29 4:30 p Confession (or by appointment w/Fr. Anthony) 5:00 p Great Vespers Sunday, August 30 9:00 AM Orthros 10:00 AM Divine Liturgy Sunday Divine Liturgy live-streamed on our Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/stanthonyspringtx/ UPCOMING ONLINE MEETINGS AND ACTIVITIES SEEKERS, ENQUIRERS & CATECHUMENS CLASS via ZOOM continues this Wednesday, August 26th at 6:30p. The class will discuss “Church Etiquette” and all are welcome to join! ARE YOU 55 OR OLDER? Join Fr. -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 196-212 brill.com/jjs Girolamo Muziano, Scipione Pulzone, and the First Generation of Jesuit Art John Marciari The Morgan Library & Museum, New York [email protected] Abstract While Bernini and other artists of his generation would be responsible for much of the decoration at the Chiesa del Gesù and other Jesuit churches, there was more than half a century of art commissioned by the Jesuits before Bernini came to the attention of the order. Many of the early works painted in the 1580s and 90s are no longer in the church, and some do not even survive; even a major monument like Girolamo Muzia- no’s Circumcision, the original high altarpiece, is neglected in scholarship on Jesuit art. This paper turns to the early altarpieces painted for the Gesù by Muziano and Scipione Pulzone, to discuss the pictorial and intellectual concerns that seem to have guided the painters, and also to some extent to speculate on why their works are no longer at the Gesù, and why these artists are so unfamiliar today. Keywords Jesuit art – Il Gesù – Girolamo Muziano – Scipione Pulzone – Federico Zuccaro – Counter-Reformation – Gianlorenzo Bernini Visitors to the Chiesa del Gesù in Rome, or to the recent exhibition of Jesuit art at Fairfield University,1 might naturally be led to conclude that Gianlorenzo 1 Linda Wolk-Simon, ed., The Holy Name: Art of the Gesù; Bernini and His Age, Exh. cat., Fair- field University Art Museum, Early Modern Catholicism and the Visual Arts 17 (Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, 2018). -

Observations on Van Dyck As a Religious Painter Thomas L

Document generated on 09/28/2021 9:09 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Observations on van Dyck as a Religious Painter Thomas L. Glen Volume 10, Number 1, 1983 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1074637ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1074637ar See table of contents Publisher(s) UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Glen, T. L. (1983). Observations on van Dyck as a Religious Painter. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 10(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.7202/1074637ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Association d'art des universités du Canada), 1983 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Observations on van Dyck as a Religions Painter* THOMAS L. GLEN McGill University When dealing with Europcan religious art of the for the main altar of the Church of St. Walburgis seventeenth century, one must inevitably contend (Fig. 2). In Rubens’ altarpiece we witness Christ with the awesome personality of Sir Peter Paul triumphant. -

Isenheim Altarpiece Restoration Finally Back on Track After Public Outcry

AiA Art News-service Isenheim Altarpiece restoration finally back on track after public outcry More than 30 conservators will treat paintings and sculptures, seven years after French culture ministry halted reckless cleaning of two panels VINCENT NOCE 7th November 2018 10:45 GMT The painted panels will be restored at Colmar’s Unterlinden Museum Photo: Ruedi Walti; © Musée Unterlinden Seven years after halting an unorthodox restoration of the Isenheim Altarpiece, French conservators have resumed work on the celebrated northern Renaissance polyptych in the hope of getting it right this time. It took only six days in 2011 for two restorers with a cloth to strip the varnish off a painted panel depicting the Temptation of Saint Anthony and to revarnish it. They then started to repeat the process on half of Saint Anthony Visiting Saint Paul. Launched before a major expansion of the Unterlinden Museum in the Alsatian region of Colmar, where the altarpiece is housed, the work was not preceded by a scientific examination. When the online magazine La Tribune de l’Art and the newspaper Libération expressed alarm at the speed of the intervention, the ensuing indignation prompted France’s culture ministry to step in and halt the pair. A study that began in 2013 concluded that no real damage had been done to the 1512-16 painting, regarded as the masterpiece of the German artist Mathis Gothart-Nithart, called Matthias Grünewald by art historians. It was a close call, nonetheless. The varnish had been left almost untouched in the darker parts but wiped off in the clearer sections. -

Download the Press

PRESS KIT www.tourisme-colmar.com PAYS DE COLMAR Summary Press service caring for you 3 Lovely Colmar 4 Tourism in Colmar 5 Not to be missed ! 6 History 7 Wander around 9 Discover Colmar differently 10 Museums 12 100% Alsace Shopping! 18 For dinner 20 Accommodation 21 An event for each season ! 22 To go further 26 How to find us ? 27 2 Press service caring for you To facilitate the organization of your reports the press service of the Tourist Office is at your disposal. We listen to you to create a program in line with your expectations. Accommodation, catering, visits... Our service takes care of you for a custom home. Presse contact [email protected] - 0033 3 89 20 69 10 3 Lovely Colmar « Colmar is a condensed version of Alsace in all that is most typically Alsatian » Identity card It is no longer necessary to extol the charms of Colmar : timbered houses, canals, pedestrian town center with many flowers and good food ... Condensed of an idyllic Prefecture of Upper-Rhin Alsace, the capital of Alsace the wines is the guardian of a lifestyle that you need to Capital of Centre-Alsace discover! 67 214 inhabitants 66.57 km² Colmar offers the intimacy of a small town combined with a rich heritage and culture. 3rd city of Alsace (population) Nestled at the foot of the vineyard, at the crossroads of major European roads, the city with multicolored houses is also the birthplace of sculptor Bartholdi, father of the Folwers city : 4 stars famous Statue of Liberty in New York and was born Hansi, the best known illustrators Climate : semi-continental of Alsace. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos