André Dussollier Excels in This Role, Managing to Be Both Comforting and Disturbing… Yes, André Is a Great Actor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lineup Berlin 2019 Booth Mgb #9

LINEUP BERLIN 2019 BOOTH MGB #9 1 PANORAMA MIDNIGHT TRAVELER A FILM BY HASSAN FAZILI & EMELIE MAHDAVIAN When the Taliban puts a bounty on Afghan director Hassan Fazili's head, he is forced to flee with his wife and two young daughters. Capturing their uncertain journey, Fazili shows both the danger and desperation of their multi-year odyssey and the tremendous love shared between them. “PARTICULARLY GIVEN THE RISE IN IGNORANCE ABOUT AN ANIMOSITY TOWARDS REFUGEES, IT’S A FILM WHICH DESERVES TO BE AS WIDELY SEEN AS POSSIBLE.” SCREEN INTERNATIONAL Old Chilly Pictures USA - Qatar - Canada - UK / 87’ / 2019 / Documentary Sales for North America: CINETIC PANORAMA SCREENINGS: EFM SCREENINGS: SUNDAY 10/02 17:00 CINESTAR 7 MONDAY 11/02 22:30 CINESTAR 7 SATURDAY 09/02 15:00 CINEMAXX 12 WEDNESDAY 13/02 14:30 COLOSSEUM 1 TUESDAY 12/02 12:45 CINEMAXX 16 FRIDAY 15/02 12:00 CINESTAR 7 THURSDAY 14/02 17:30 CINEMAXX 11 2 3 EFM MARKET WHATEVER HAPPENED TO MY REVOLUTION BY JUDITH DAVIS With: Judith Davis, Malik Zidi, Claire Dumas Angèle, a young and restless activist, never stops crusading for social justice, losing sight of her friends, family and love in the process. EFM SCREENINGS: “A RAGING, HILARIOUS COMEDY.” TELERAMA FRIDAY 08/02 14:45 CINEMAXX 12 MONDAY 11/02 9:30 Agat Films - Apsara Films / France / 88’ / 2018 / Feature Film CINEMAXX 14 4 SLAM BY PARTHO SEN-GUPTA With: Adam Bakri, Rachael Blake, Abbey Azziz Ricky is a young Arab Australian whose peaceful suburban life is turned on its head when his sister, Ameena, disappears without trace. -

Download Catalogue

LIBRARY "Something like Diaz’s equivalent "Emotionally and visually powerful" of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville" THE HALT ANG HUPA 2019 | PHILIPPINES | SCI-FI | 278 MIN. DIRECTOR LAV DIAZ CAST PIOLO PASCUAL JOEL LAMANGAN SHAINA MAGDAYAO Manilla, 2034. As a result of massive volcanic eruptions in the Celebes Sea in 2031, Southeast Asia has literally been in the dark for the last three years, zero sunlight. Madmen control countries, communities, enclaves and new bubble cities. Cataclysmic epidemics ravage the continent. Millions have died and millions more have left. "A dreamy, dreary love story packaged "A professional, polished as a murder mystery" but overly cautious directorial debut" SUMMER OF CHANGSHA LIU YU TIAN 2019 | CHINA | CRIME | 120 MIN. DIRECTOR ZU FENG China, nowadays, in the city of Changsha. A Bin is a police detective. During the investigation of a bizarre murder case, he meets Li Xue, a surgeon. As they get to know each other, A Bin happens to be more and more attracted to this mysterious woman, while both are struggling with their own love stories and sins. Could a love affair help them find redemption? ROMULUS & ROMULUS: THE FIRST KING IL PRIMO RE 2019 | ITALY, BELGIUM | EPIC ACTION | 116 MIN. DIRECTOR MATTEO ROVERE CAST ALESSANDRO BORGHI ALESSIO LAPICE FABRIZIO RONGIONE Romulus and Remus are 18-year-old shepherds twin brothers living in peace near the Tiber river. Convinced that he is bigger than gods’ will, Remus believes he is meant to become king of the city he and his brother will found. But their tragic destiny is already written… This incredible journey will lead these two brothers to creating one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen, Rome. -

Filmverleih- Unternehmen in Europa

Filmverleih- unternehmen in Europa André Lange und Susan Newman-Baudais unter Mitarbeit von Thierry Hugot Einleitung .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Hinweise zur Benutzung ........................................................................................................................ 5 Kapitel 1 Filmverleihunternehmen in Europa .........................................................................9 1.1 Ein Überblick 1.2 Wirtschaftliche Analyse INHALT Kapitel 2 Individuelle Gesellschaftsprofi le ............................................................................ 23 AT Österreich ..............................................................25 BE Belgien ...................................................................29 BG Bulgarien ...............................................................41 CH Schweiz ..................................................................45 CZ Tschechische Republik ............................................51 DE Deutschland ...........................................................59 DK Dänemark ..............................................................67 EE Estland ...................................................................73 ES Spanien ..................................................................79 FI Finnland .................................................................95 FR Frankreich ............................................................101 -

Dossier Presse Joseph

Les Films de la Croisade en coproduction avec Iota Production et uFilm en association avec uFund avec la participation de France Télévisions Joseph l’insoumis Une fiction de 90’ inspirée de la vie du Père Joseph Wrésinski, fondateur d’ATD Quart Monde avec Jacques Weber, Anouk Grinberg Nicolas Louis, Patrick Descamps, Laurence Côte Salomé Stévenin, Anne Coesens, Isabelle de Hertogh Un film de Caroline Glorion Projet labellisé réalisé avec le soutien de : CNC, Région Aquitaine, Communauté Française de Belgique, Commission Européenne, Conseil Général de Gironde, Ville de Bordeaux, Ministère de la Santé et des Sports - Délégation à l’information et à la Communication, L’Acsé –Fonds Images de la Diversité, Observatoire National de la Pauvreté, Caisse des Dépôts, Fondation Bettencourt Schueller, Association Georges Hourdin, du Programme Media de l’Union Européenne, de Soficinéma 5 Développement et de TV5 Monde Joseph l’insoumis Le Rachaï Joseph l’insoumis Début des années 60, un bidonville aux portes de Paris. Une poignée de familles survivent sous des abris de fortune dans une misère effroyable et une violence quotidienne. Un homme, le Père Joseph Wrésinski, décide de s’installer au milieu de ceux qu’il appelle « son peuple ». Parmi ces familles, celle de Jacques. Sa vie va être transformée par sa rencontre avec le Père Joseph. La sienne mais la vie aussi de ceux qui vont rejoindre le combat de ce curé révolutionnaire. Un combat contre l’assistance et la charité qui dit-il « enfoncent les pauvres dans l’indignité Distribution artistique Joseph -

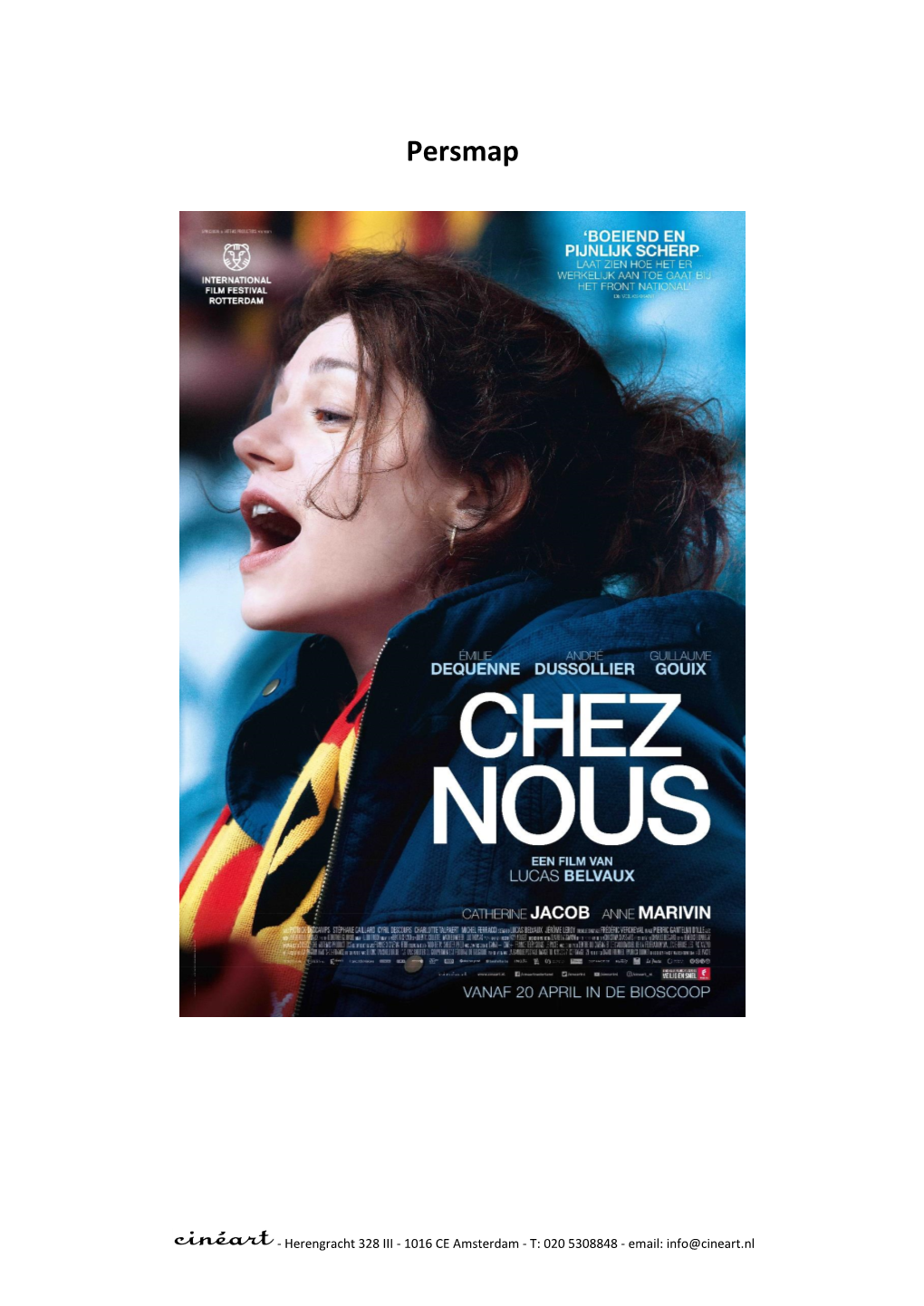

Download Persmap

PERSMAP - Herengracht 328 III - 1016 CE Amsterdam - T: 020 5308848 - F: 020 5308849 - email: [email protected] 38 TÉMOINS Een film van Lucas Belvaux Yvan Attal Sophie Quinton Nicole Garcia Wanneer Louise terugkomt van een zakenreis verneemt ze dat er een moord gepleegd is in haar straat. Niemand heeft iets gezien of gehoord, iedereen sliep. Lijkt het… Pierre, haar man, was aan het werk. Hij was op zee. Lijkt het… De politie start het onderzoek, maar ook de pers roert zich. Beetje bij beetje komt Louise erachter dat 38 mensen iets gehoord of gezien hebben en dat haar man wel eens één van hen zou kunnen zijn… Openingsfilm International Film Festival Rotterdam 2012 Speelduur: 99 min. - Land: België/ Frankrijk - Jaar: 2011 - Genre: Drama Release datum: 28 juni 2012 Distributie: Cinéart Meer informatie: Publiciteit & Marketing: Cinéart Janneke De Jong Herengracht 328 III 1016 CE Amsterdam Tel: +31 (0)20 5308848 Email: [email protected] Persmap en foto’s staan op: www.cineart.nl Persrubriek inlog: cineart / wachtwoord: film - Herengracht 328 III - 1016 CE Amsterdam - T: 020 5308848 - F: 020 5308849 - email: [email protected] CAST Pierre Morvand Yvan Attal Louise Morvand Sophie Quinton Sylvie Loriot Nicole Garcia Kapitein Léonard François Feroleto Anne Natacha Régnier Petrini Patrick Descamps Advocaat Didier Sandre Directeur Bernard Mazzinghi Groepsleider Laurent Fernandez Jonge politieagent Pierre Rochefort Gewelddadige man Philippe Résimont Getuigen Sébastien Libessart Dimitri Rataud Vincent Le Bodo Anne-Sophie Pauchet Chef van Louise Jean-Pierre -

MY KING (MON ROI) a Film by Maïwenn

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRESOR PRESENTS MY KING (MON ROI) A film by Maïwenn “Bercot is heartbreaking, and Cassel has never been better… it’s clear that Maïwenn has something to say — and a clear, strong style with which to express it.” – Peter Debruge, Variety France / 2015 / Drama, Romance / French 125 min / 2.40:1 / Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound Opens in New York on August 12 at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Opens in Los Angeles on August 26 at Laemmle Royal New York Press Contacts: Ryan Werner | Cinetic | (212) 204-7951 | [email protected] Emilie Spiegel | Cinetic | (646) 230-6847 | [email protected] Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman | Shotwell Media | (310) 450-5571 | [email protected] Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | PR & Promotion | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tony (Emmanuelle Bercot) is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on the turbulent ten-year relationship she experienced with Georgio (Vincent Cassel). Why did they love each other? Who is this man whom she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free. LOGLINE Acclaimed auteur Maïwenn’s magnum opus about the real and metaphysical pain endured by a woman (Emmanuelle Bercot) who struggles to leave a destructive co-dependent relationship with a charming, yet extremely self-centered lothario (Vincent Cassel). -

Jaarverslag 2019

Jaarverslag 2019 Dit verslag biedt een analyse van de acties die screen.brussels fund vzw heeft ondernomen om zijn doelstellingen te verwezenlijken. Het bestaat uit vijf grote hoofdstukken: 1. Herhaling van de doelstellingen en taken van screen.brussels fund 2. Balans van de investeringen in de producties 3. Balans van de uitgevoerde acties 4. Boekhoudkundige balans 2019 Dit jaar staat meer bepaald in het teken van de consolidatie van de databases met professionals uit de audiovisuele sector en van de lancering van een platform om de aanvragen voor fondsen elektronisch te kunnen indienen. Dit jaar kenmerkt zich ook door de betaling van de subsidies in vele schijven (verkiezingsjaar). 1 screen.brussels fund vzw – Balans jaar 2019 1. Herhaling van de doelstellingen en taken 1.1. Context Op 2 mei 2016 lanceerde het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest zijn nieuwe strategie die moest zorgen voor een betere toegankelijkheid van het Brusselse audiovisuele aanbod voor alle Brusselse, Belgische en internationale betrokkenen. Deze strategie werd met name concreet door de oprichting van het overkoepelende merk screen.brussels. Dit bestaat uit 4 entiteiten: - screen.brussels film commission (het voormalige Brussels Film Office, onder leiding van visit.brussels) - screen.brussels cluster (de sectorale cluster, ondergebracht bij hub.brussels) - screen.brussels business (financiering van Brusselse audiovisuele bedrijven via finance.brussels) - screen.brussels fund (het Brusselse coproductiefonds) 1.2. Doelstellingen Het doel van de vzw screen.brussels binnen deze organisatie is de ontwikkeling en promotie van de audiovisuele sectoren in het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest, en de organisatie van alle taken die verband houden met de visuele sectoren in het algemeen. -

Dussollier Hands Baer

PHOTOS ARNAUD BORREL / ILLUSTRATION OLIVIER AND MARC-ANTOINE COULON DUSSOLLIER JEAN-LOUIS LIVI JEAN-LOUIS ANDRE A FILM BY MARC A FILMBY PRESENTS HANDS DUGAIN MARINA ND MARC-ANTOINE COULON A PHOTOS ARNAUD BORREL / ILLUSTRATION OLIVIER PHOTOS ARNAUD BORREL / ILLUSTRATION EDOUARD BAER R O GN: DIMITRI SIMON F SI L DE A N I G I R O JEaN-LouiS Livi PRESENTS aNdRE MaRiNa EDOUARd DUSSOLLIER HANDS BAER (UNE EXECUTION ORDINAIRE) a FiLM BY MaRC DUGAIN STudioCaNaL iNTERNaTioNaL MaRkETiNg 1, place du Spectacle 92863 issy-les-Moulineaux Cedex 9 France Phone: +33 1 71 35 11 13 RUNNING TIME : 1h45 www.studiocanal.com FRENCH RELEASE DATE: FEBRUARY 3, 2010 STaLiN To aNNa : “doN’T FoRgET YouR HaNdS, i WiLL CoME WiTH MY PaiN.” Fall 1952. A young urologist and healer who works in a hospital in the Moscow suburbs is desperate to fall pregnant by her husband, a disillusioned doctor who is only surviving because of the love binding him to his wife. To her great terror, she is secretly called upon to look after Stalin who is sick and who has just fired his personal physician. The dictator worms his way into their relationship and creates a relationship with the young woman involving a tangle of secrets and manipulation. By turns friendly and perverse, the monster reveals his skills in the art of terror as never seen before. STaLiN : “i’vE goTTEN Rid oF EvERYoNE WHo WaS iNdiSPENSaBLE. SiNCE THEN, THEY’vE SHoWN ME THaT THEY WEREN’T.” I TERVIEW WITH marc dugain Your book, “The Officers’ Ward” was adapted for the screen in 1991 AN ORDINARY EXECUTION is about the last days of Stalin and covers by François Dupeyron. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Joachim Lafosse Bérénice Bejo Cédric Kahn

LES FILMS DU WORSO AND VERSUS PRODUCTION PRESENT BÉRÉNICE BEJO CÉDRIC KAHN A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE Les films du Worso and Versus production present A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE WITH BÉRÉNICE BEJO AND CÉDRIC KAHN 100MIN - BELGIUM/FRANCE - 2016 - SCOPE - 5.1 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ALIBI COMMUNICATIONS INTERNATIONAL SALES Brigitta PORTIER In Cannes: Unifrance – Village International 5, rue Darcet French mobile: +33 6 28 96 81 65 (from May10th) 75017 Paris International mobile: +32 4 77 98 25 84 Phone: +33 1 44 69 59 59 [email protected] Press materials available for download on www.le-pacte.com SYNOPSIS After 15 years of living together, Marie and Boris decide to get a divorce. Marie had bought the house in which they live with their two daughters, but it was Boris who had completely renovated it. Since he cannot afford to find another place to live, they must continue to share it. When all is said and done, neither of the two is willing to give up. We sense that the two girls are quite disrupted by the situation. At the same time, they give INTERVIEW WITH the impression that they are quite comprehensive regarding the very strict rules imposed by Marie on Boris, just like they’re comprehensive regarding the father’s transgressions: “It’s not JOACHIM LAFOSSE his day”, Jade will tell Margaux, so as to explain the embarrassment which follows Boris’s presence in the house on a Wednesday afternoon. Marie seems to sets all the rules. She’s in charge. Boris does not have a say, but in a way this situation allows What triggered the idea of the film? How did you write it? him to set his own rule. -

WILD Grasscert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES)

WILD GRASS Cert 12A (LES HERBES FOLLES) A film directed by Alain Resnais Produced by Jean‐Louis Livi A New Wave Films release Sabine AZÉMA André DUSSOLLIER Anne CONSIGNY Mathieu AMALRIC Emmanuelle DEVOS Michel VUILLERMOZ Edouard BAER France/Italy 2009 / 105 minutes / Colour / Scope / Dolby Digital / English Subtitles UK Release date: 18th June 2010 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐Mail: [email protected] or FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films – [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 www.newwavefilms.co.uk WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) SYNOPSIS A wallet lost and found opens the door ‐ just a crack ‐ to romantic adventure for Georges (André Dussollier) and Marguerite (Sabine Azéma). After examining the ID papers of the owner, it’s not a simple matter for Georges to hand in the red wallet he found to the police. Nor can Marguerite retrieve her wallet without being piqued with curiosity about who it was that found it. As they navigate the social protocols of giving and acknowledging thanks, turbulence enters their otherwise everyday lives... The new film by Alain Resnais, Wild Grass, is based on the novel L’Incident by Christian Gailly. Full details on www.newwavefilms.co.uk 2 WILD GRASS (LES HERBES FOLLES) CREW Director Alain Resnais Producer Jean‐Louis Livi Executive Producer Julie Salvador Coproducer Valerio De Paolis Screenwriters Alex Réval Laurent Herbiet Based on the novel L’Incident -

Activity Results for 2015

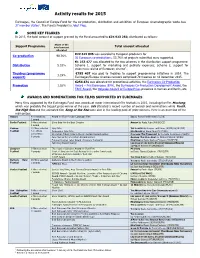

Activity results for 2015 Eurimages, the Council of Europe Fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematographic works has 37 member states1. The Fund’s President is Jobst Plog. SOME KEY FIGURES In 2015, the total amount of support granted by the Fund amounted to €24 923 250, distributed as follows: Share of the Support Programme total amount Total amount allocated allocated €22 619 895 was awarded to European producers for Co-production 90.76% 92 European co-productions. 55.76% of projects submitted were supported. €1 253 477 was allocated to the two schemes in the distribution support programme: Distribution 5.03% Scheme 1, support for marketing and publicity expenses; Scheme 2, support for awareness raising of European cinema2. Theatres (programme €795 407 was paid to theatres to support programming initiatives in 2014. The 3.19% support) Eurimages/Europa Cinemas network comprised 70 theatres on 31 December 2015. €254 471 was allocated for promotional activities, the Eurimages Co-Production Promotion 1.02% Award – Prix Eurimages (EFA), the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award, the FACE Award, the Odyssée-Council of Europe Prize, presence in Cannes and Berlin, etc. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR FILMS SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES Many films supported by the Eurimages Fund won awards at major international film festivals in 2015, including the film Mustang, which was probably the biggest prize-winner of the year. Ida attracted a record number of awards and nominations while Youth, the High Sun and the animated film Song of the Sea were also in the leading pack of prize-winners.