My Child and My Life: Sacrificial Obligation and Chaucer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Qanon Conspiracy

THE QANON CONSPIRACY: Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy THE QANON CONSPIRACY: PRESENTED BY Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy NETWORK CONTAGION RESEARCH INSTITUTE POLARIZATION AND EXTREMISM RESEARCH POWERED BY (NCRI) INNOVATION LAB (PERIL) Alex Goldenberg Brian Hughes Lead Intelligence Analyst, The Network Contagion Research Institute Caleb Cain Congressman Denver Riggleman Meili Criezis Jason Baumgartner Kesa White The Network Contagion Research Institute Cynthia Miller-Idriss Lea Marchl Alexander Reid-Ross Joel Finkelstein Director, The Network Contagion Research Institute Senior Research Fellow, Miller Center for Community Protection and Resilience, Rutgers University SPECIAL THANKS TO THE PERIL QANON ADVISORY BOARD Jaclyn Fox Sarah Hightower Douglas Rushkoff Linda Schegel THE QANON CONSPIRACY ● A CONTAGION AND IDEOLOGY REPORT FOREWORD “A lie doesn’t become truth, wrong doesn’t become right, and evil doesn’t become good just because it’s accepted by the majority.” –Booker T. Washington As a GOP Congressman, I have been uniquely positioned to experience a tumultuous two years on Capitol Hill. I voted to end the longest government shut down in history, was on the floor during impeachment, read the Mueller Report, governed during the COVID-19 pandemic, officiated a same-sex wedding (first sitting GOP congressman to do so), and eventually became the only Republican Congressman to speak out on the floor against the encroaching and insidious digital virus of conspiracy theories related to QAnon. Certainly, I can list the various theories that nest under the QAnon banner. Democrats participate in a deep state cabal as Satan worshiping pedophiles and harvesting adrenochrome from children. President-Elect Joe Biden ordered the killing of Seal Team 6. -

This Is a Test

‘GOODNIGHT FOR JUSTICE: QUEEN OF HEARTS’ PRODUCTION BIOS LUKE PERRY (Executive Producer) – In 1989, Luke Perry was chosen for a starring role on the internationally popular television series “Beverly Hills 90210,” in which he portrayed the brooding but sensitive Dylan McCay. The highly-rated program won a Golden Globe Award for Best Dramatic Television series in 1991. Perry made his feature film debut in a starring role in “8 Seconds,” the remarkable account of champion bull rider Lane Frost, which he co-produced. His serious devotion to the inspirational legend of Lane Frost led him to train vigorously for 18 months in order to master the techniques of bull riding and to be able to perform many of his own stunts during production. Other film credits include Columbia’s “Fifth Element”, directed by Luc Besson, “Riot for Showtime,” “Normal Life,” “American Strays” and “The Florentine,” in which he co-starred with Chris Penn, Jim Belushi, Michael Madsen and Mary Stuart Masterson. Perry made his debut on Broadway in the critically acclaimed musical The Rocky Horror Picture Show, where he portrayed Brad, the character originally played by Barry Bostwick in the cult film classic. In 2004, Perry appeared onstage in London opposite Allyson Hannigan in When Harry Met Sally. Not one to be typecast because of his work on “90210,” Perry’s television credits include a myriad of roles, including a lead in the NBC drama “Windfall,” HBO’s “John From Cincinnati,” starring for two seasons on “Jeremiah,” the Showtime Network sci-fi series, a multi-episode arc on HBO’s critically acclaimed series “Oz,” in which he portrayed a televangelist convicted of fraud, as well as roles in Hallmark Channel productions “Johnson County War,” “Supernova,” “A Gunfighter’s Pledge” and “Angel and the Badman.” Perry starred in “Goodnight for Justice,” Hallmark Movie Channel’s highest rated movie of all time. -

PEOPLE PLAYING THEMSELVES MY FECIS Thesis Submitted in Partial

PEOPLE PLAYING THEMSELVES MY FECIS Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Visual & Critical Studies By Kelly Elizabeth Lloyd Department/Program Visual & Critical Studies The School of the Art Institute of Chicago Summer, 2015 Thesis Committee: Primary Advisor/1st Reader: Romi Crawford, Associate Professor Visual and Critical Studies, School of the Art Institute of Chicago 2nd Reader: Shannon Stratton, Chief Curator, Museum of Arts and Design 3rd Reader: Hamza Walker, Adjunct Professor, Painting & Drawing, School of the Art Institute of Chicago You’re a vacuum cleaner, and at the same time you’re the guy selling it. Dustin Gold The creator will never participate in anything other than the creation of a small dirty deposit, a succession of small dirty deposits juxtaposed. Jacques Lacan I hate a movie that will end by telling you that the first thing you should do is learn to love yourself. That is so insulting and condescending, and so meaningless. My characters don't learn to love each other or themselves. Charlie Kaufman Look Like Yourself Is it particularly important that it is Matt Le Blanc playing himself in Episodes? No, not really. If I know things about Matt and Joey (the character who Matt played on Friends from 1994-2004 and on Joey from 2004-2006) I am rewarded with jokes here and there, but often the details of these actor’s lives are actually irrelevant to the storyline. When people play themselves, what matters most is not that they are themselves, but that they are a specific kind of an actor. -

Contag 100 011

UB-INNSBRUCK FAKULTATSBIBLIOTHEK THEOLOGIE Z3 CONTAG 100 011 VOLUME 11 SPRING 2004 EDITOR ANDREW MCKENNA I LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ADVISORY EDITORS REN£ GIRARD, STANFORD UNIVERSITY JAMES WILLIAMS, SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY EDITORIAL BOARD REBECCA ADAMS CHERYL K3RK-DUGGAN UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME MEREDITH COLLEGE MARK ANSPACH PAISLEY LIVINGSTON £COLE POLYTECHNIQUE, PARIS MCGILL UNIVERSITY CESAREO BANDERA CHARLES MABEE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA ECUMENICAL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, DETROIT DIANA CULBERTSON KENT STATE UNIVERSITY JOZEF NIEWIADOMSKI THEOLOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE, LINZ JEAN-PIERRE DUPUY STANFORD UNIVERSITY, £COLE POLYTECHNIQUE SUSAN NOWAK SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PAUL DUMOUCHEL UNIVERSITE DU QUEBEC A MONTREAL WOLFGANG PALAVER UNIVERSITAT INNSBRUCK ERIC GANS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES MARTHA REINEKE UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN IOWA SANDOR GOODHART WHITMAN COLLEGE TOBIN SIEBERS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ROBERT HAMERTON-KELLY STANFORD UNIVERSITY THEE SMITH EMORY UNIVERSITY HANS JENSEN AARHUS UNIVERSITY, DENMARK MARK WALLACE SWARTHMORE COLLEGE MARK JUERGENSMEYER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, EUGENE WEBB SANTA BARBARA UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON Rates for the annual issue of Contagion are: individuals $10.00; institutions $32. The editors invite submission of manuscripts dealing with the theory or practical application of the mimetic model in anthropology, economics, literature, philosophy, psychology, religion, sociology, and cultural studies. Essays should conform to the conventions of The Chicago Manual of Style and should not exceed a length of 7,500 words including notes and bibliography. Accepted manuscripts will require final sub- mission on disk written with an IBM compatible program. Please address correspondence to Andrew McKenna, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, Loyola University, Chicago, IL 60626. Tel: 773-508-2850; Fax: 773-508-2893; Email: [email protected]. Member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals CELJ © 1996 Colloquium on Violence and Religion at Stanford ISSN 1075-7201 Cover illustration: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Envy, 1557. -

GLOBAL BURDEN of ARMED VIOLENCE 2011 ISBN 978-1-107-60679-1 Takes an Integrated an Takes 2011

he Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011 takes an integrated approach to the complex and volatile dynamics of armed GENEVA T violence around the world. Drawing on comprehensive country- DECLARATION level data, including both conflict-related and criminal violence, it estimates that at least 526,000 people die violently every year, more than three-quarters of them in non-conflict settings. It highlights that the 58 countries with high rates of lethal violence account for two- thirds of all violent deaths, and shows that one-quarter of all violent GLOBAL deaths occur in just 14 countries, seven of which are in the Americas. New research on femicide also reveals that about 66,000 women GLOBAL BURDEN VIOLENCE and girls are violently killed around the world each year. 2 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 This volume also assesses the linkages between violent death rates and socio-economic development, demonstrating that homicide rates are higher wherever income disparity, extreme poverty, and hunger are high. It challenges the use of simple analytical classifications and policy responses, and offers researchers and policy-makers new tools for studying and tackling different forms of violence. of ARMED VIOLENCE o f ARMED BURDEN Photos Top left: Rescuers evacuate a wounded person from Utoeya, Norway, July 2011. © Morten Edvarsen/AFP Photo Lethal Centre left: Morgue workers transport a coffin to be buried along with other unidentified bodies found in mass graves, Durango, Mexico, June 2011. © Jorge Valenzuela/Reuters Encounters Bottom right: An armed fighter walks past a burnt-out armed vehicle in the Abobo 2011 district of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2010. -

For Immediate Release

‘LIVING OUT LOUD’ PRODUCTION BIOS JACK GROSSBART (Executive Producer) – Jack Grossbart is an independent producer who has produced nearly 40 telefilms in the last 20 years. Partnered with Linda Kent in Grossbart Kent Productions, their recent TV movie “Why I wore Lipstick to my Mastectomy,” starring Sarah Chalke, earned them the 2007 Gracie Award, a 2007 Humanitas Prize nomination, and a 2007 Emmy nomination for Outstanding Made for Television Movie. Before forming Grossbart Kent Productions, Grossbart was partnered with Joan Barnett in Grossbart/Barnett Productions for 15 years, producing telefilms for CBS, NBC, ABC and HBO, as well as some of the newly emerging cable channels. Among their productions have been “Any Mother’s Son,” “The Marriage Fool,” starring Walter Matthau and Carol Burnett, “Unforgivable,” starring John Ritter, the award winning “Something to Live For: The Alison Gertz Story,” “Leave of Absence” starring Brian Dennehy and Jacqueline Bisset, “Last Wish” starring Patty Duke and Maureen Stapleton, and HBO’s “The Comrades of Summer,” starring Joe Mantegna. Grossbart executive produced the Emmy nominated miniseries “Echoes in the Darkness,” based on the best selling Joseph Wambaugh book, The Preppie Murder. In the half-hour series arena, Grossbart executive produced the Valerie Bertinelli series “Sydney” for CBS and “Café Americain” for NBC. Grossbart graduated from Rutgers University with a B.A. in English and Dramatic Arts and started working in the mailroom at ICM, where he worked his way up to become an agent in their theater department. After four years, he moved to Los Angeles to work for the William Morris Agency where he was an agent in the television department for five years. -

![Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8197/infanticide-dictionary-entry-m-1078197.webp)

Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications Theology, Department of 11-1-2011 Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M. Therese Lysaught Marquette University Published version. "Infanticide [Dictionary Entry]," in Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Eds. Joel B. Green, Jacqueline E. Lapsley, Rebekah Miles, and Allen Verhey. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Publishing Group, 2011. Publisher Link. Used with permission. © 2011 Baker Publishing Group. No print copies may be produced without obtaining written permission from Baker Publishing Group. Inequality See Equality Infanticide Infanticide refers to intentional practices that cause the death of newborn infants or, second arily, older children. Scripture and the Christian tradition are un equivocal: infanticide is categorically condemned. Both Judaism and Christianity distinguished themselves in part via their opposition to wide spread practices of infanticide in their cultural contexts. Are Christian communities today like wise distinguished, Of, like many of their Israel ite forebears, do they profess faith in God while worshiping Molech? Infanticide in Scripture Infanticide stands as an almost universal practice across history and culture (Williamson). Primary justifications often cite economic scarcity or popu lation control needs, although occasionally infan ticide flourished in prosperous cultural contexts (Levenson) . Infanticide or, more precisely, child sacrifice forms the background of much of the OT. Jon Levenson argues that the transformation of child sacrifice, captured in the repeated stories of the death and resurrection of the beloved and/or first born son, is at the heart of the Judea-Christian tradition. The Israelites found themselves among peoples who practiced child sacrifice, particularly sacrifice of the firstborn son. In Deut. 12:31 it is said of the inhabitants of Canaan that "they even burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods" (d. -

Child Protection and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2020

Child Protection and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2020 Report No. 71, 56th Parliament Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee August 2020 Legal Affairs and Community Safety Committee Chair Mr Peter Russo MP, Member for Toohey Deputy Chair Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs1 Members Mr Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani Mrs Laura Gerber MP, Member for Currumbin Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister2 Ms Corrine McMillan MP, Member for Mansfield Committee Secretariat Telephone +61 7 3553 6641 Fax +61 7 3553 6699 Email [email protected] Technical Scrutiny +61 7 3553 6601 Secretariat Committee Web Page www.parliament.qld.gov.au/lacsc Acknowledgements The committee acknowledges the assistance provided by the Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women and the Queensland Parliamentary Library. 1 Mr Rob Molhoek MP, Member for Southport, was a substitute for the Deputy Chair, Mr James Lister MP, Member for Southern Downs, on 10 August 2020 2 Mr Chris Whiting MP, Member for Bancroft was a substitute for Mrs Melissa McMahon MP, Member for Macalister, on 27 July 2020. Child Protection and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2020 Contents Abbreviations iii Chair’s foreword v Recommendation vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Role of the committee 1 1.2 Inquiry process 1 1.3 Policy objectives of the Bill 1 1.4 Government consultation on the Bill 2 1.5 Should the Bill be passed? 3 2 Background to the Bill 4 2.1 Adoption as a means of providing permanency 4 2.1.1 Legislation in other jurisdictions 4 2.1.2 Research on adoption -

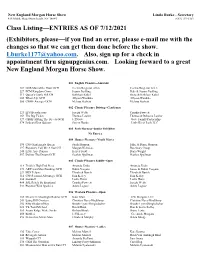

Class Listing—ENTRIES AS of 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, Please—If You Find an Error, Please E-Mail Me with the Changes So That We Can Get Them Done Before the Show

New England Morgan Horse Show Linda Burke - Secretary 435 Middle Road Horseheads, NY 14845 (607) 739-6169 Class Listing—ENTRIES AS OF 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, please—if you find an error, please e-mail me with the changes so that we can get them done before the show. [email protected]. Also, sign up for a check in appointment thru signupgenius.com. Looking forward to a great New England Morgan Horse Show. 001 English Pleasure--Amateur 102 GLB Man of the Hour GCH Cecilia Bergeron Allen Cecilia Bergeron Allen 227 FCM Kingdom Come Jeanne Fuelling Dale & Jeanne Fuelling 311 Queen's Castle Hill CH Kathleen Kabel Steve & Kathleen Kabel 380 What's Up GCH Allyson Wandtke Allyson Wandtke 566 CBMF Avenger GCH Melissa Beckett Melissa Beckett 002 Classic Pleasure Driving--Gentlemen 123 LPS Beaudacious Joseph Webb Cynthia Fawcett 169 The Big Ticket Thomas Lawlor Thomas & Rebecca Lawlor 327 CBMF Hitting The Streets GCH Jeff Gove Gove Family Partnership 574 Ledyard Don Quixote Steven Handy Little Bit of Luck LLC 003 Park Harness--Junior Exhibitor No Entries 004 Hunter Pleasure--Youth Mares 190 CFS Gentlemen's Queen Sarah Munson Mike & Diane Munson 197 Playmor's Call Me A Star CH Morgan Nicholas Rosemary Croop 248 Little Acre Dancia Kelsey Scott Darla Wright 507 Deliver The Dream GCH Scarlett Spellman Scarlett Spellman 005 Classic Pleasure Saddle--Open 118 Treble's High End Piece Amanda Zsido Amanda Zsido 173 ADC Last Man Standing GCH Robin Vergato James & Robin Vergato 229 MJS Eclipse Elizabeth Burick Elizabeth Burick 314 CFF Personal Advantage GCH -

Current, February 07, 2005

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2000s) Student Newspapers 2-7-2005 Current, February 07, 2005 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, February 07, 2005" (2005). Current (2000s). 247. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s/247 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2000s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 37 February 7, 2e05 See page 12 Get Ready for Valentine's Day T HECURRENTONLlNE.COM ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. UN I VERSI~OF M ISSO~RI - S~LOUIS l~ Forum focuses on The art of kissing .. .in public student retention BY BEN SWOFFORD do to make UMSL better," wrote. · ·~'_~·'"_ ' " __ _ '_ ' _ ~' _ _ _ ' __ _ ' __ _ ____ N ' _ __ __ ' "_'_." _ _ _ StaffWlriter Student Services Coordinator Joe Flees, in an email to prospective student focus, group attendees. Students had the chance to The discussion focused on student comment and complain about their experiences with academic advising Ii' experience with the University on campus, at the advising center, at academic advising system on Monday, the individual colleges and within Ian. 31. majors. _ The Office of Student Affairs at 'There are four types of advising," UM-St. Louis sponsored a series of Crockett said during . the discussion. discussions in the Millennium Student "You have got a new University-wide Center on retention and lldvismg. -

Hollywood for Habitat for Humanity

Hollywood for Habitat for Humanity (HFHFH) is an Sponsors have included: entertainment industry partnership with Habitat for 1stCall Studio Equipment, ABC, A+E Networks, AEG, Humanity of Greater Los Angeles (HFH GLA) that was CAA, Disney, The Ellen Show, Esquire , Facebook, Fox founded in 2000 by Screenwriter, Director and Producer Broadcasting Company, Glamour, Google, Grey’s Anatomy, Randall Wallace (Braveheart, We Were Soldiers, Guerilla Union, HBO, Harmonix , The Hollywood Reporter, Secretariat) to encourage the entertainment industry to House & Garden, International Creative Management, Jon support Habitat for Humanity's goal of eliminating Bon Jovi Soul Foundation , Lava Bear Films, MTV Networks, substandard housing worldwide. HFHFH works with talent the Music Builds Tour, Music for Relief, MySpace, NCIS, Oprah Winfrey’s An gel Network, Overbrook and industry leaders who support the organization through Entertainment, Overture Films, Pa ramount Pictures, Ricky donations, volunteer hours and advocacy. Martin Foundation, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Staples Center Foundation, Theory of a Deadman , Turner Broadcast Founding Advisory Board Members: Systems, United Talent Agency, Universal Pictures, Vanity Melanie Cook (Partner, Ziffren Brittenh am L LP), Gale Fair, Variety, The Walt Disney Company, Warner Bros., Anne Hurd (CEO, Valhalla Motion Pi ctures), Erin Wheelhouse Entertainment, W!ldbrain Entertainment, William Rank (President & Adams), and David Wirtschafter Morris Endeavor Entertainment, Women in Film and Ziffren (William Morris Endeavor Entertainment). Brittenham LLP. Habitat for Supporters and volunteers have Founded in 1976, included: Humanity has built over 500,000 30 Seconds To Mars, John Abraham, homes, housing more than 2.3 million David Arquette, Patricia Arquette, people wor ldwide, in more than 90 Christian Bale, Jacinda Barrett, Camille countries. -

Profiles in Caring 2019

Saint Francis Foundation Profiles 2019 in Caring Saint Francis Foundation Saint Francis Foundation Board of Directors Colleagues Officers: Lynn B. Rossini Lynn B. Rossini* Vice President and Chief Development Officer Vice President and Chief Development Officer Amy Griffin Buzzell, M.B.A. John F. Rodis*, M.D., M.B.A., FACHE Regional Director of Operations, Philanthropy President, Saint Francis Hospital Brenda Carbone John A. Green Special Events Manager Chairman Whitney Hubbs Dionne, M.B.A. Victor J. Dowling Director of Communications Vice Chairman & Stewardship Programs Karl J. Badey, CPA, MST Melida Gilbert Treasurer Department Assistant Barbara C. Gordon Lisa Irizarry Secretary Development Officer Susan Joyse Director of Philanthropy Active Directors: Jay Mullarkey Charles G. Andrew, Jr. Howard W. Orr Genie Lomba Karl J. Badey, CPA, MST Linda Pendergast* Database and Financials Administrator Nelson Bayron William Reis Ana Moore Sam Chang Kimberlee Richard Executive Associate Ranjana Chawla John F. Rodis*, M.D., M.B.A. Andrew R. Crumbie Stuart Rosenberg, M.B.A. Mark O’Donnell, Ph.D. Edward P. Danek, Jr. Lynn B. Rossini* Senior Grant Writer Hema N. de Silva, M.D. Nancy Taylor Marc Spencer Victor J. Dowling Thomas R. Trumble Development Officer Reverend Henry C. Frascadore Overseers: Kate Sullivan Vaghini Charles F. Gfeller, Esq. Most Rev. LeRoy Bailey, Jr. Development Associate Heidi Grise Brad Davis Clare Walker Barbara C. Gordon Lisa Gerrol Data Analyst John A. Green Ronald D. Jarvis Sasa Harriott Peter G. Kelly, Esq. James T. Healey, Jr. Karl J. Krapek Marcy A. Hollander Irene O’Connor Theresa Hopkins-Staten Pauline N. Olsen, M.D.