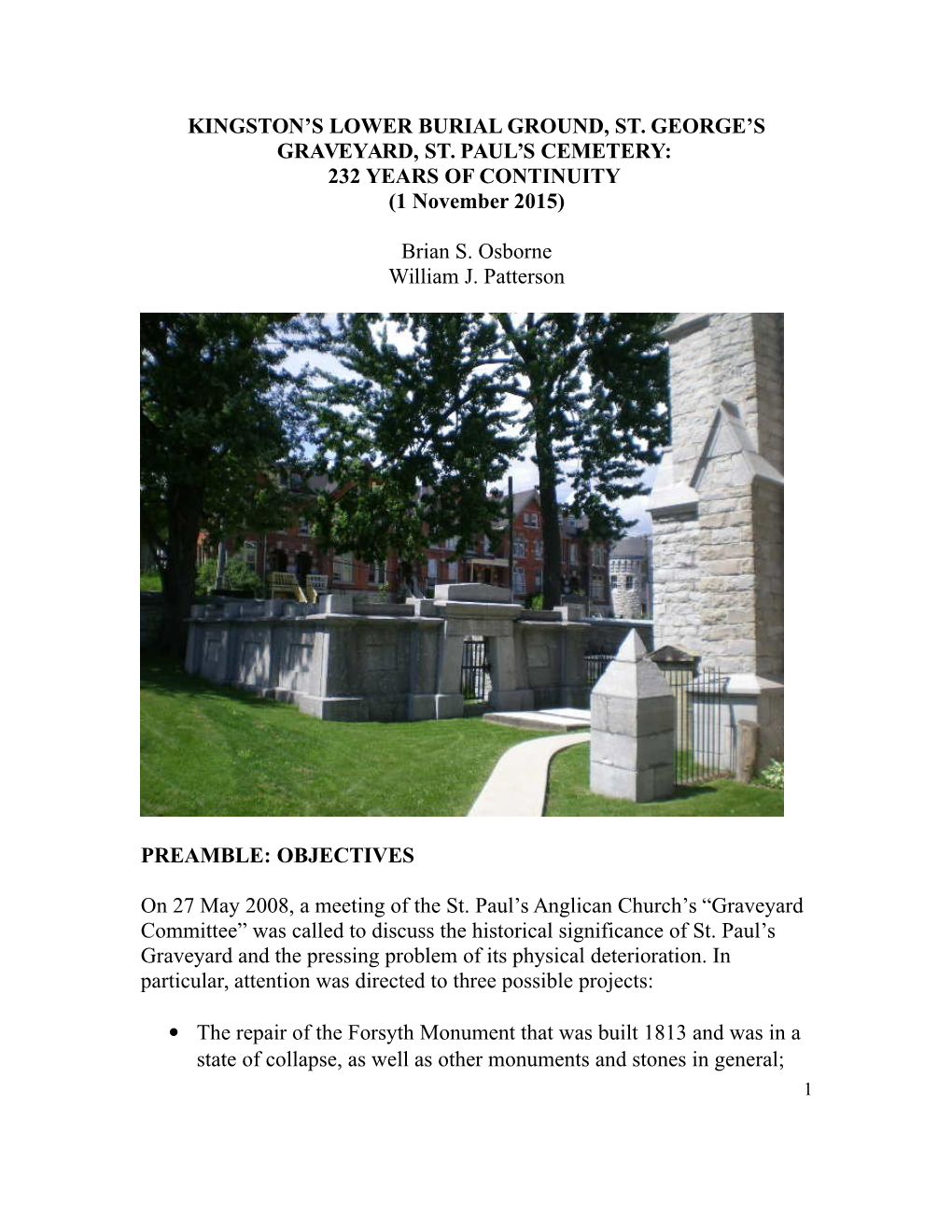

Kingston's Lower Burial Ground, St. George's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index by Subject

- 155 - Russell, Peter Cruikshank: The Early life and letters of the Honourable Peter Russell, XXIX, 121. Cruikshank and Hunter (ed.): The Correspondence ~ the Honourable Peter Russell, with allied documents relating to his administration of the government of Upper Canada during the o~ficial term of Lieutenant-Governor J.G. Simcoe, while on leave of absence, 3 v. Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1932-36. Firth: The Administration of Peter Russell, 1796-1799, XLVIII, 163. Hunter: The Probated wills of men prominent in the public affairs of Upper Canada, XXIII, 328. Ryerse, Captain Samuel Ryerse: Port Ryerse; its harbour and former trade, XX, 145. Tasker: The United Empire Loyalist settlement at Long Point, Lake Erie, II, 9. Ryerson, Egerton Hathaway: Early schools of Toronto, XXIII, 312. Hathaway: The River Credit and the Mississaugas, XXVI, 432. McGregor: Egerton Ryerson, Albert Carman, and the founding of Albert College, Belleville, LXIII, 205. Onn: Egerton Ryerson's philosophy of education, something borrowed or something new?, LXI, 77. Ryerson, George Sissons (ed.): George pyeraon to Sir Peregrine Maitland, 9 June, 1826, XLIV, 23. Ryerson, Col. Joseph Locke: The Loyalists in Ontario, XXX, 181. Tasker: The United Empire Loyalist settlement at Long Point, Lake Erie, II, 9. S St. Catharines Clark: The Ml'.nicipal loan fund in Upper Canada, XVIII, 44. St. Davids, Niagara County Ruley: Along the Four Mile Creek, XLVIII, Ill. Saint Domingo Cruikshank: Simcoe's mission to Saint Domingo, XXV, 78. St. Ives, Middlesex County Jury: St. Ives, XLI, 133. Saint Joseph Island, Lake Huron Hamil: An Early settlement on St. Joseph Island, LIII, 251. -

The Effect of British Colonial Policy on Public Educational Institutions in Upper Canada, 1784-1840

THE EFFECT OF BRITISH COLONIAL POLICY ON PUBLIC EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN UPPER CANADA, 1784-1840 by Walter E. Downes Thesis presented to the School of Graduate Studies as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Education- '' LIBRARIES \ **»rty Ol °^ UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA OTTAWA, CANADA, 1974 Downes, Ottawa, Canada, 1974 UMI Number: DC53364 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53364 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENT This thesis was prepared under the direction of Professor Mary Mulcahy, Ph.D., of the Faculty of Education of the University of Ottawa. The writer is indebted to Dr. Mulcahy for her interest, direction and encouragement. CURRICULUM STUDIORUM Walter E. Downes was born September 15t 1932, in Peterborough, Ontario. He received the Bachelor of Arts degree from Queen's University in 1956 and the Master of Education degree from the University of Toronto in 1966. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter page INTRODUCTION vii PART I BACKGROUND 1 I. -

Chronology of North King's Town

Chronology of North King’s Town, Kingston by Jennifer McKendry PhD Note Index! Revised 15 May 2018 Photography by Jennifer McKendry unless otherwise noted [email protected] “Study Area” refers to the parts of North King’s Town under discussion NORTH KING’S TOWN Page 2 of 196 “[The site of Frontenac School on Cowdy at Adelaide Streets] is on an eminence, which commands a view of the whole city and of the district for miles around. From the first flat can be distinctly seen the G.T.R. bridge at Kingston Mills and the lapping waters of the historic Cataraqui river can be traced from its meeting with the majestic St Lawrence almost to Kingston Mills six miles away. Far down in the township of Pittsburg, as far as the eye can see, can be viewed greenclad slopes extending to so great a distance that their outline is lost in the blue haze of the atmosphere. To the north the same view is presented while to the west the grandeur of the outlook is past description. The scene from the building is kaleidoscopic in character and the view from its apex will surpass anything at present in existence in the city.” Daily British Whig, 13 June 1896 NORTH KING’S TOWN Page 3 of 196 Table of Contents Years 10,000 BCE – 1200 AD ......................................................................................... 9 Years 1600-1673 ........................................................................................................... 10 Years 1673-1758 .......................................................................................................... -

The Revd. John Stuart, DD, UEL of Kingston, UC

FROM-THE- LIBRARYOF TR1NITYCOLLEGETORDNTO FROM-THE- LIBRARY-OF TWNITYCOLLEGETORQNTO & FROM THE LIBRARY OF THE LATE COLONEL HENRY T. BROCK DONATED NOVEMBER. 1933 The Revd. John Stuart D.D., U.E.L. OF KINGSTON, U. C. and His Family A Genealogical Study by A. H. YOUNG 19 Contents PACK Portraits of Dr. John Stuart and his wife, Jane Okill viii Preface 1 Note on the Origin and Distribution of the Stuart Family in Canada 7 The Revd. John Stuart and Jane Okill 9 I. George-Okill Stuart and his Wives 10 II. John Stuart, Jr., and Sophia Jones 12 III. Sir James Stuart, Bart., and Elizabeth Robertson 27 IV. Jane Stuart 29 V. Charles Stuart and Mary Ross 29 VI. The Hon. Andrew Stuart and Marguerite Dumoulin 30 VII. Mary Stuart and the Hon. Charles Jones, M.L.C 41 VIII. Ann Stuart and Patrick Smyth 44 Extract from Dr. Strachan's Funeral Sermon on Dr. John Stuart 47 The Only Sermon of Dr. John Stuart known to be extant 55 Addenda . 62 Preface little study of the distinguished Stuart family, founded by the Revd. John Stuart, D.D., of Kings THISton, has grown out of researches for a Life of Bishop Strachan, who called him "my spiritual father." Perusal of original letters to the Society for the Propa gation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, together with the Society's Journals and Annual Reports from 1770 to 1812-, gives one a good idea of "the little gentleman," as he was called, notwithstanding his six feet four inches, even before he left the Province of New York in 1781. -

Religious Print Culture and the British and Foreign Bible Society in Canada, 1820-1904

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 Religious Print Culture and the British and Foreign Bible Society in Canada, 1820-1904 Barnard, Stuart Wayne Barnard, S. W. (2016). Religious Print Culture and the British and Foreign Bible Society in Canada, 1820-1904 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27618 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2909 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “Religious Print Culture and the British and Foreign Bible Society in Canada, 1820-1904” by Stuart Wayne Barnard A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2016 © Stuart Wayne Barnard 2016 Abstract This study addresses the central question of how Canadians came to obtain the bibles they read in nineteenth century Canada. Historians of religion in Canada have recognized the importance of evangelicalism in nineteenth century Canada, but have rooted their analyses largely in denominational and intellectual frameworks. This study seeks to examine Protestant evangelicalism through its outworking in the British and Foreign Bible Society, one of the largest voluntary societies in Canada in this period. -

One World, Two Churches

Building Identities: St. George’s Anglican Churches, Kingston, Upper Canada, 1792-1826 CARMEN NIELSON VARTY Churches are articulate visual statements declaring the preoccupations, aspirations and ideologies of their builders. Whether a church is a small, weatherboard structure in a rural parish or a large imposing stone cathedral, its architectural style can tell historians a great deal about the people who built and attended it and the kind of religion they practised. This is particularly evident if we consider St. George’s Anglican Church in Kingston, Upper Canada during the first fifty years of the congrega- tion’s history. The first St. George’s church was built in 1792; what would eventually become St. George’s Cathedral was built in 1826 to meet the needs of an expanding congregation. What is fascinating is how different these churches were, architecturally; it is clear that they were really quite different in terms of the aspirations and assumptions of their respective congregations. However, historians have tended to focus attention on the formal architectural styles of large urban churches and their symbolic importance for participants and observers. Thus, we know a great deal less about the vernacular architecture of small rural churches like the one at Kingston and the meaning that this church had for those who attended it. Certainly a good deal has been written about the St. George’s Church built in 1826. Several articles explore what historians imply is the “real” St. George’s. Moreover, as one of the few neo-classical churches built in the nineteenth century in Upper Canada St. -

F2053 ARCHIBALD HOPE YOUNG COLLECTION Description And

F2053 ARCHIBALD HOPE YOUNG COLLECTION Description and Finding Aid Prepared by Christopher Hogendoorn 2014 A..H. Young collection ARCHIBALD HOPE YOUNG COLLECTION Dates of creation 1809? – [2000?] Extent 2.4 m of textual records 2 artefacts 24 graphic items Biographical sketch Archibald Hope Young, educator and historian, was known as “Archie” to generations of Trinity College students. Born 6 February 1863 in Sarnia, Canada West, to Archibald and Annie (née Wilson) Young, he attended Sarnia Public, Private, and High Schools before going to Upper Canada College 1878-1882, where he was Head Boy in his final year. He matriculated at the University of Toronto in 1882 as a Prince of Wales Scholar and graduated with a BA in Modern Languages in 1887. He was also the president of the University of Toronto Modern Language Club 1886-1887. He received a BA ad eundem in 1892 from the University of Trinity College, and his MA in 1893. He also studied for a period of time at the University of Strasbourg. In 1916 he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Civil Law, honoris causa , by the University of King’s College. Before coming to Trinity College, Young was the assistant master in Drummondville High School 1884-1885 and an assistant junior master in Upper Canada College 1887-1889. He was also a Modern Languages master 1887-1892 and an assistant housemaster 1889-1891. Young first became associated with Trinity College in 1892, when he was hired as a lecturer on Modern Languages and Philology. He held this position until 1900, when he was promoted to Professor of Modern Languages and Philology. -

HISTORICAL PAPERS 1998 Canadian Society of Church History

HISTORICAL PAPERS 1998 Canadian Society of Church History Annual Conference University of Ottawa 29-30 May 1998 Edited by Bruce L. Guenther ©Copyright 1998 by the authors and the Canadian Society of Church History Printed in Canada ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Historical Papers June 2/3 (1988)- Annual. A selection of papers delivered at the Society’s annual meeting. Place of publication varies. Continues: Proceedings of the Canadian Society of Church History, ISSN 0842-1056. ISSN 0848-1563 ISBN 0-9696744-0-6 (1993) 1. Church History—Congresses. 2. Canada—Church history—Congresses. l. Canadian Society of Church history. BR570.C322 fol. 277.1 C90-030319-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Papers The Gospel of Success in Canada: Charles W. Gordon (Ralph Connor) as Exemplar ROBERT A. KELLY 5 The Church as Employer: Social Ideology and Ecclesial Practice During Labour Conflict OSCAR COLE-ARNAL 17 The Central Canada Presbytery: Prospects, Perplexities, Problems ELDON HAY 29 Through the Eyes of The Tattler: Concerns of Baptist Youth in Rural Nova Scotia, 1933-1940 RUSSELL PRIME 45 The Calgary Local Council of Women: Traditional Female Christianity in Action (1895-1897 and 1912-1933) ANNE WHITE 67 “Casting Sand in the Eyes”: Conrad Brasco’s Literary Dispute with the Orthodox Reformed Preachers in Elberfeld, 1704-1706 DOUGLAS H. SHANTZ 89 Building Identities: St George’s Anglican Churches, Kingston, Upper Canada, 1792-1826 CARMEN NIELSON VARTY 113 CSCH President’s Address “Give me that old-time Religion”: The Postmodernist Plot Of the Theologians PAUL H. FRIESEN 129 4 Contents Please Note: Papers by Elizabeth Elbourne, Thomas Evans, Gillis J. -

Inventaire Du Fonds Chauveau

Inventaire du Fonds Chauveau de la Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée nationale Réalisé par Clément LeBel avec la collaboration de Claire Jacques et Martin Pelletier (dernière mise à jour : janvier 2017) Fonds Chauveau Introduction L’acquisition du fonds et son morcellement En 1892, le gouvernement québécois se portait acquéreur de la bibliothèque de Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, le premier des premiers ministres du Québec (1867-1873), décédé deux ans plus tôt1. La collection originale, destinée à la Bibliothèque de la Législature, était constituée de 6723 documents, soit 3512 volumes reliés et 3211 brochures. Le Fonds Chauveau compte aujourd’hui 3715 ouvrages. En un peu plus de cent ans, il s’est donc effrité de près de la moitié de son contenu2. On aurait sans doute pu sauvegarder un plus grand nombre d’imprimés si on avait choisi de leur accorder, dès le départ, une attention particulière. C’est un peu ce que recommandait Charles Langelier, secrétaire de la province, lorsqu’il faisait part à l’Assemblée législative, le 30 décembre 1890, des intentions du gouvernement « d’acheter la bibliothèque de l’honorable M. Chauveau et d’en faire une collection à part, qui garderait le nom de son ancien propriétaire ». Ce souhait de conserver la collection intacte était, du reste, partagé par quelques contemporains de Chauveau, comme en témoignent la correspondance relative à l’acquisition de la bibliothèque par l’État de même que divers articles parus dans les journaux de l’époque3. Les autorités du temps en ont cependant décidé autrement puisque nous savons aujourd’hui qu’après l’achat seuls certains livres sélectionnés ont bénéficié d’un traitement privilégié. -

Manuscript Collection in the Toronto Public Libraries

GUIDE TO THE MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION IN THE TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARIES TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARIES 1954 GUIDE TO THE MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION IN THE TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARIES TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARIES 1954 PRINTED IN CANAllA THORN PRESS, TORONTO PREFATORY NOTE The manuscript collection of the Toronto Public Libra~ies consists mainly of Canadian, and more particularly of Upper CanadIan historical manuscripts, with a few British and American items. There are several large sets of personal papers and many single pieces, in cluding diaries, account-books, letter-books, and single documents. The collection has grown steadily since it was begun in 1886 with the purchase by Dr. James Bain, historian, collector, and first librarian, of the manuscript, An account of the Seven Years' War, 1757-1759. About the turn of the century half a dozen large sets were given to the library by Toronto families whose members have been outstanding in the early history of the country. Through the years the collection has been en riched by the gifts of generous and history-minded benefactors, and by purchase. In the more recent acquisitions there is greater emphasis on business history, and on regions farther afield from Toronto. A Preliminary guide to the manuscripts was published in 1940. It was intended to be no more than a rough guide to be used until sufficient work on the material warranted the publication of a definitive catalogue. Now, fourteen years later, it is again necessary to apologize for the long uncalendared sets, the unidentified or undated single pieces. The work goes steadily on, but if the public are to know and use the large number of acquisitions since 1940, another preliminary guide is needed. -

International Fugitives and the Law in British Orth America/Canada, 1819

Emptying the Den of Thieves: International Fugitives and the Law in British orth America/Canada, 1819-1910 by Bradley Miller A Thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © Copyright by Bradley Miller, 2012 ABSTRACT Emptying the Den of Thieves: International Fugitives and the Law in British North America/Canada, 1819-1910 Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Bradley Miller Department of History, University of Toronto This thesis examines how the law dealt with international fugitives. It focuses on formal extradition and the cross-border abduction of wanted criminals by police officers and other state officials. Debates over extradition and abduction reflected important issues of state power and civil liberty, and were shaped by currents of thought circulating throughout the imperial, Atlantic, and common law worlds. Debates over extradition involved questioning the very basis of international law. They also raised difficult questions about civil liberties and human rights. Throughout this period escaped American slaves and other groups made claims for what we would now call refugee status, and argued that their surrender violated codes of law and ideas of justice that transcended the colonies and even the wider British Empire. Such claims sparked a decades-long debate in North America and Europe over how to codify refugee protections. Ultimately, Britain used its imperial power to force Canada to accept such safeguards. Yet even as the formal extradition system developed, an informal system of police abductions operated in the Canadian-American borderlands. This system defied formal law, but it also manifested sophisticated local ideas about community justice and transnational legal order. -

City Council Agenda

Exhibit A Notice of Intention to Pass a By-Law to Designate 235 Frontenac Street / 136 Alfred Street, 890 Front Road, 484 Albert Street, 620 Princess Street, 946 Old Kingston Mills Road, 3702 Highway 38, 3581 Princess Street, 1216 Unity Road and 2586 Kepler Road To be of Cultural Heritage Value and Interest Pursuant to the Provisions of the Ontario Heritage Act (R.S.O. 1990, Chapter 0.18) Take Notice that the Council of The Corporation of the City of Kingston intends to pass by-laws under Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, R.S.O. 1990, Chapter 0.18, to designate the following lands to be of cultural heritage value and interest: 235 Frontenac Street and 136 Alfred Street (Lots 903-910, Plan A13, City of Kingston, County of Frontenac and Lots 911-912, 939-940, 945-946, Plan A 12, Except Part 1 on Reference Plan 13R-11181; City of Kingston, County of Frontenac), known as the Kingston Collegiate and Vocational Institute. The property, locally known as KCVI, represents the inception of secondary school education in Ontario. KCVI can trace its roots back to 1786 when it was originally established by The Reverend John Stuart as the first secondary school in Ontario. The earliest of the current buildings date from 1911 with additions added in 1931, 1959 and 1968. KCVI has further associative value with well- known local architects Joseph Power and Colin Drever. KCVI has a long list of influential alumni such as former Members of federal and provincial parliament, former City Mayors, as well as members of the Kingston rock band The Tragically Hip and soloist David Usher.