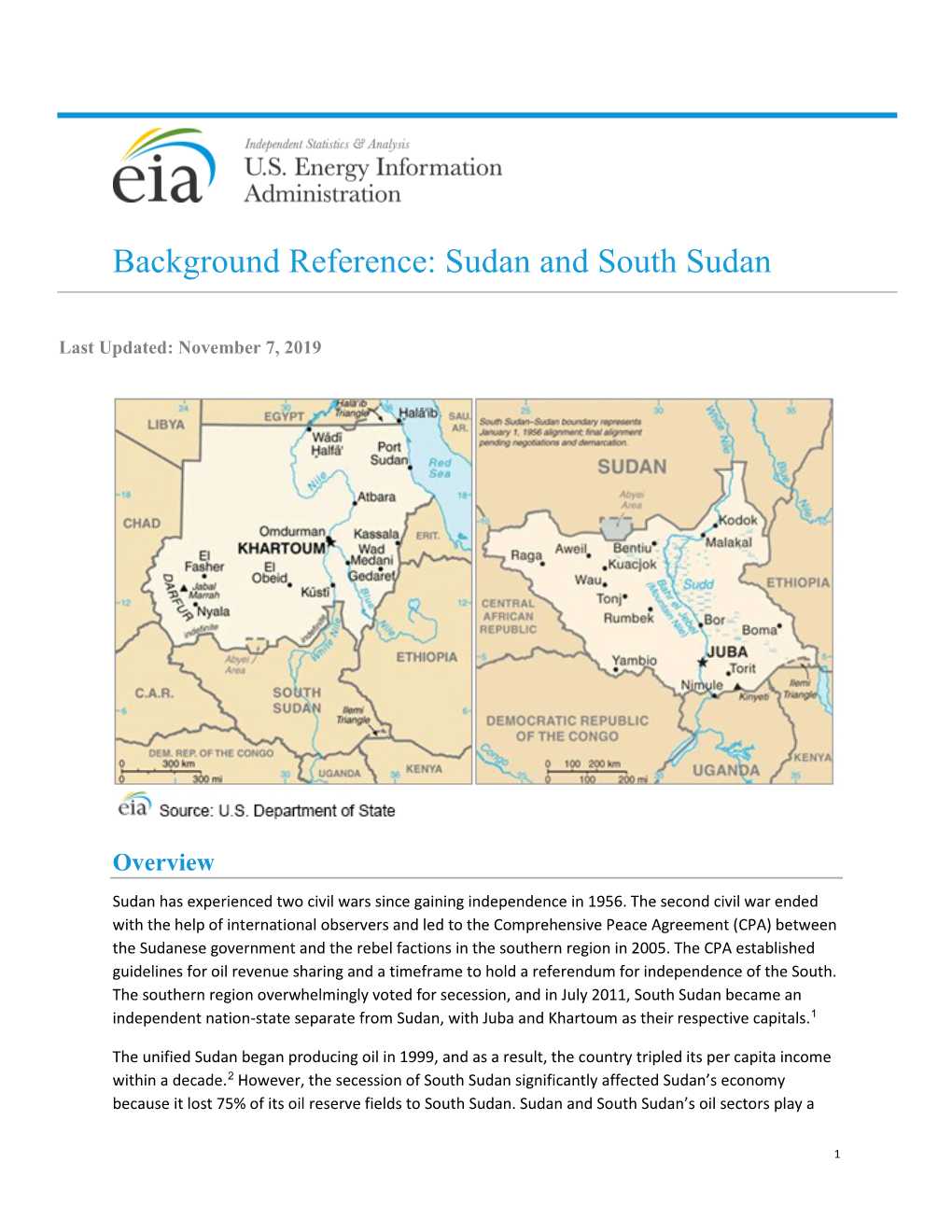

Background Reference: Sudan and South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Addis Ababa Agreement on the Problem of South Sudan

THE ADDIS ABABA AGREEMENT ON THE PROBLEM OF SOUTH SUDAN Draft Organic Law to organize Regional Self-Government in the Southern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Sudan In accordance with the provisions of the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Sudan and in realization of the memorable May Revolution Declaration of June 9, 1969, granting the Southern Provinces of the Sudan Regional Self-Government within a united socialist Sudan, and in accordance with the principle of the May Revolution that the Sudanese people participate actively in and supervise the decentralized system of the government of their country, it is hereunder enacted: Article 1. This law shall be called the law for Regional Self-Government in the Southern Provinces. It shall come into force and a date within a period not exceeding thirty days from the date of Addis Ababa Agreement. Article 2. This law shall be issued as an organic law which cannot be amended except by a three- quarters majority of the People’s National Assembly and confirmed by a two-thirds majority in a referendum held in the three Southern Provinces of the Sudan. CHAPTER I: DEFINITIONS Article 3. a) ‘Constitution’ refers to the Republican Order No. 5 or any other basic law replacing or amending it. b) ‘President’ means the president of the Democratic Republic of the Sudan. c) ‘Southern Provinces of the Sudan’ means the Provinces of Bahr El Ghazal, Equatoria and Upper Nile in accordance with their boundaries as they stood January 1, 1956, and other areas that were culturally and geographically a part of the Southern Complex as may be decided by a referendum. -

Nomads' Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future Action

Nomads’ Settlement in Sudan: Experiences, Lessons and Future action (STUDY 1) Copyright © 2006 By the United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retreival system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Printed by SCPP Editor: Ms: Angela Stephen Available through: United Nations Development Programme in Sudan House 7, Block 5, Avenue P.O. Box: 913 Khartoum, Sudan. www.sd.undp.org The analysis and policy recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations, including UNDP, its Executive Board or Member States. This study is the work of an independent team of authors sponsored by the Reduction of Resource Based Conflcit Project, which is supported by the United Nations Development Programme and partners. Contributing Authors The Core Team of researchers for this report comprised of: 1. Professor Mohamed Osman El Sammani, Former Professor of Geography, University of Khartoum, Team leader, Principal Investigator, and acted as the Report Task Coordinator. 2. Dr. Ali Abdel Aziz Salih, Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Khartoum. Preface Competition over natural resources, especially land, has become an issue of major concern and cause of conflict among the pastoral and farming populations of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Sudan, where pastoralists still constitute more than 20 percent of the population, is no exception. Raids and skirmishes among pastoral communities in rural Sudan have escalated over the recent years. -

ENERGY COUNTRY REVIEW Sudan

ENERGY COUNTRY REVIEW Sudan keyfactsenergy.com KEYFACTS Energy Country Review Sudan Most of Sudan's and South Sudan's proved reserves of oil and natural gas are located in the Muglad and Melut Basins, which extend into both countries. Natural gas associated with oil production is flared or reinjected into wells to improve oil output rates. Neither country currently produces or consumes dry natural gas. In Sudan, the Ministry of Finance and National Economy (MOFNE) regulates domestic refining operations and oil imports. The Sudanese Petroleum Corporation (SPC), an arm of the Ministry of Petroleum, is responsible for exploration, production, and distribution of crude oil and petroleum products in accordance with regulations set by the MOFNE. The SPC purchases crude oil at a subsidized cost from MOFNE and the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). The Sudan National Petroleum Corporation (Sudapet) is the national oil company in Sudan. History Sudan (the Republic of the Sudan) is bordered by Egypt (north), the Red Sea, Eritrea, and Ethiopia (east), South Sudan (south), the Central African Republic (southwest), Chad (west) and Libya (northwest). People lived in the Nile valley over 10,000 years ago. Rule by Egypt was replaced by the Nubian Kingdom of Kush in 1700 BC, persisting until 400 AD when Sudan became an outpost of the Byzantine empire. During the 16th century the Funj people, migrating from the south, dominated until 1821 when Egypt, under the Ottomans, Country Key Facts Official name: Republic of the Sudan Capital: Khartoum Population: 42,089,084 (2019) Area: 1.86 million square kilometers Form of government: Presidential Democratic Republic Language: Arabic, English Religion Sunni Muslim, small Christian minority Currency: Sudanese pound Calling code: +249 KEYFACTS Energy Country Review Sudan invaded. -

PETRONAS' Journey in Human Capital Development

UNCTAD 17th Africa OILGASMINE, Khartoum, 23-26 November 2015 Extractive Industries and Sustainable Job Creation Building Institutional Capabilities: PETRONAS' journey in Human Capital Development By Mohamad Yusof Shahid Chairman, PETRONAS Sudan Operations The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNCTAD. Building Institutional Capabilities: PETRONAS' journey in Human Capital Development Presented by Mr. M Yusof Shahid Chairman, PETRONAS Sudan Operations © 2015 PETROLIAM NASIONAL BERHAD (PETRONAS) All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the permission of the copyright owner. ©Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS) 2015 1 AGENDA PETRONAS is a Major Multinational Oil and Gas Company 01 PETRONAS: Structured Approach for Human Resources Development 02 PETRONAS in Sudan 04 The Future © 2015 PETROLIAM NASIONAL BERHAD (PETRONAS) All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the permission of the copyright owner. ©Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS) 2015 2 Agile Development & Growth Transformation of an NOC into a global energy champion REVENUE (USD bil) Domestic Regulator Domestic Player Going International Global Player 100 Ventured into • Ventured into Iraq 2009 Turkmenistan -

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Lead Authors:∗ Tamara Gurevich and Peter Herman Contributing Authors: Nabil Abbyad, Meryem Demirkaya, Austin Drenski, Jeffrey Horowitz, and Grace Kenneally Version 1.00 Abstract This document provides technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset. The Dynamic Gravity dataset provides extensive country and country pair information for a total of 285 countries and territories, annually, between the years 1948 to 2016. This documentation extensively describes the methodology used for the creation of each variable and the information sources they are based on. Additionally, it provides a large collection of summary statistics to aid in the understanding of the resulting Dynamic Gravity dataset. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional devel- opment of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. ∗We thank Renato Barreda, Fernando Gracia, Nuhami Mandefro, and Richard Nugent for research assistance in completion of this project. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Nomenclature . .3 1.2 Variables Included in the Dataset . .3 1.3 Contents of the Documentation . .6 2 Country or Territory and Year Identifiers 6 2.1 Record Identifiers . -

Beyond Juba Building Consensus on Sustainable Peace in Uganda

Beyond Juba Building Consensus on Sustainable Peace in Uganda Why Being Able to Return Home Should be Part of Transitional Justice: Urban IDPs in Kampala and their quest for a Durable Solution Working Paper No. 2 March 2010 Beyond Juba A transitional justice project of the Faculty of Law, Makerere University, the Refugee Law Project and the Human Rights & Peace Centre and conflict-related issues in Uganda and is a direct response to the Juba peace talks between the Government of Uganda and the Lord’s Resistance Army. diff of society Development Agency (SIDA) and the Norwegian Embassy. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS neighbourhoods of Kireka-Banda (Acholi Quarters), Namuwongo and Naguru in Kampala. The research team consisted of Paulina Wyrzykowski and Benard Okot Kasozi. This paper was written by Paulina Wyrzykowski and Benard Okot Kasozi with valuable input from Dr. Chris Dolan. The authors are also grateful to Moses C. Okello for his assistance in the initial conceptualization and planning and to all the members of the urban Internally Displaced Persons communities who contributed their time and opinions to this research, and who were kind enough to share with us their personal and deeply moving experiences. Beyond Juba Contents Acknowledgements Acronyms ................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Recommendations.... ....................................................................................3 -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Soil and Oil

COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 i COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 ii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE © 2006 by the Coalition for International Justice. All rights reserved. February 2006 iii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CIJ wishes to thank the individuals, Sudanese and not, who graciously contributed assistance and wisdom to the authors of this research. In particular, the authors would like to express special thanks to Evan Raymer and David Baines. February 2006 iv 25E 30E 35E SAUDI ARABIA ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT LIBYA Red Lake To To Nasser Hurghada Aswan Sea Wadi Halfa N u b i a n S aS D e s e r t ha ah raar a D De se es re tr t 20N N O R T H E R N R E D S E A 20N Kerma Port Sudan Dongola Nile Tokar Merowe Haiya El‘Atrun CHAD Atbara KaroraKarora RIVER ar Ed Damer ow i H NILE A d tb a a W Nile ra KHARTOUM KASSALA ERITREA NORTHERN Omdurman Kassala To Dese 15N KHARTOUM DARFUR NORTHERN 15N W W W GEZIRA h h KORDOFAN h i Wad Medani t e N i To le Gedaref Abéche Geneina GEDAREF Al Fasher Sinnar El Obeid Kosti Blu WESTERN Rabak e N i En Nahud le WHITE DARFUR SINNAR WESTERN NILE To Nyala Dese KORDOFAN SOUTHERN Ed Damazin Ed Da‘ein Al Fula KORDOFAN BLUE SOUTHERN Muglad Kadugli DARFUR NILE B a Paloich h 10N r e 10N l 'Arab UPPER NILE Abyei UNIT Y Malakal NORTHERN ETHIOPIA To B.A.G. -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. P-3753-SU REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONALDEVELOPMENT TO THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS ON A PROPOSED SDR 11.6 MILLION (US$12.0MILLION) CREDI' TO THE DEMOCRATICREPUBLIC OF SUDAN Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A PETROLEUM TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT June 19, 1984 Public Disclosure Authorized This documenthas a restricteddistribution and may be used by recipientsonly in the performanceof their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Unit = Sudanese Pound (LSd) LSd 1.00 = US$0.77 US$1.00 = LSd 1.30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS GMRD = Geological and Mineral Resources Department GPC = General Petroleum Corporation MEM = Ministry of Energy and Mines NEA = National Energy Administration NEC National Electricity Corporation PSR = Port Sudan Refinery WNPC = White Nile Petroleum Corporation WEIGHTS AND MEASURES bbl = barrel BD = barrels per day GWh = gigawatt hour kgoe = kilograms of oil equivalent KW = kilowatt LPG = liquid petroleum gas MMCFD = million cubic feet per day MT = metric tons MW = megawatt NGL = natural gas liquids TCF = trillion cubic feet toe = tons of oil equivalent GOVERNMENT OF SUDAN FISCAL YEAR July 1 - June 30 FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF SUDAN PETROLEUMTECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT CREDIT AND PROJECT SUMMARY Borrower : Democratic Republic of Sudan Amount : SDR 11.6 million (US$12.0million equivalent) Beneficiary : The Ministry of Energy and Mining Terms : Standard Project Objectives : The project would strengthen the national petroleum administration,support the Government'sefforts to promote the explorationfor hydrocarbons,and help address issues that have been raised by the discovery of oil and gas in the country. -

Conference Programme and Opening Ceremony

Registration Conference Programme and Opening Ceremony Monday 23 November 11:00- 12:00 9:00 to 18:00 Registration and badge distribution Press Conference (Friendship Hall) (by Cubic Globe) (Friendship Hall) UNCTAD: Mr. Samuel Gayi, Head of Special Unit on Commodities For all meeting participants, including: Government of Sudan: - speakers H.E. Dr. Ahmed Mohamed Mohamed Sadig Al-Karouri, Minister of Minerals - officials from Governments H.E. Dr. Mohamed Zayed Awad Musa, Minister of Petroleum and Gas - academics Mr. Saud Al Birair, President, Sudanese Businessmen and Employers Federation - NGO - civil society - press - students 19:30-19:45 19:50-21:00 21:00-23:00 Official exhibition Opening Ceremony (Friendship Hall) Cocktail Dinner opening Recitation of the Holy Coran H.E. Dr. Ahmed Mohamed Mohamed Sadig Al-Karouri, Minister of Minerals, Sudan, President of the Conference Mr. Samuel Gayi, Head, Special Unit on Commodities, UNCTAD Ms. Marta Ruedas, UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator, Sudan Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, Secretary-General of United Nations Conference on Trade and Development H.E. Dr. Mohamed Zayed Awad Musa, Minister of Petroleum and Gas, Sudan H.E. Mr. Omer Hassan Ahmed Al Bashir, President of the Republic of the Sudan 1 17th OILGASMINE Programme - semi-final version as of 25 Nov 2015.docx Tuesday 24 November 08:30- 10:30 Session 1 Upstream potential in Sudan's extractive industries Chair: H.E. Dr. Azhari A. Abdalla, Vice-President of the High Committee of the OILGASMINE Conference, Minister of Petroleum and Gas, Sudan Moderator: Mr. Azhan Ali, President, Petrodar Operating Co. Ltd, Sudan Investment climate in Sudan: Laws and Regulations Mr. -

Turkana, Kenya): Implications for Local and Regional Stresses

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Early syn-rift igneous dike patterns, northern Kenya Rift (Turkana, Kenya): Implications for local and regional stresses, GEOSPHERE, v. 16, no. 3 tectonics, and magma-structure interactions https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02107.1 C.K. Morley PTT Exploration and Production, Enco, Soi 11, Vibhavadi-Rangsit Road, 10400, Thailand 25 figures; 2 tables; 1 set of supplemental files CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT basins elsewhere in the eastern branch of the East African Rift, which is an active rift, several studies African Rift. (Muirhead et al., 2015; Robertson et al., 2015; Wadge CITATION: Morley, C.K., 2020, Early syn-rift igneous dike patterns, northern Kenya Rift (Turkana, Kenya): Four areas (Loriu, Lojamei, Muranachok-Muru- et al., 2016) have explored interactions between Implications for local and regional stresses, tectonics, angapoi, Kamutile Hills) of well-developed structure and magmatism in the upper crust by and magma-structure interactions: Geosphere, v. 16, Miocene-age dikes in the northern Kenya Rift (Tur- ■ INTRODUCTION investigating stress orientations inferred from no. 3, p. 890–918, https://doi.org /10.1130/GES02107.1. kana, Kenya) have been identified from fieldwork cone lineaments and caldera ellipticity (dikes were Science Editor: David E. Fastovsky and satellite images; in total, >3500 dikes were The geometries of shallow igneous intrusive sys- insufficiently well exposed). Muirhead et al. (2015) Associate Editor: Eric H. Christiansen mapped. Three areas display NNW-SSE– to N-S– tems -

Rapid Assessment Report the Impact of Drought in Red Sea State, Sudan

Rapid Assessment Report On The impact of Drought in Red Sea State, Sudan 6 April 2018 Early Warning Early Action (EWEA) Initiative, FAO Sudan Rapid Assessment on the impact of drought in Red Sea State Early Warning Early Action (EWEA) Initiative, FAO Sudan Contents Page Acronyms and abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment Highlights ............................................................................................................................ 3 1. OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................. 5 3. ASSESSED AREAs ........................................................................................................................ 5 4. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 6 5. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................ 6 6. LIVELIHOOD PROFILE AND POPULATION ................................................................................. 7 7. RAINFALL AND KHOR BARAKA FLOODING ............................................................................... 8 8. LIVESTOCK ...................................................................................................................................