Meningitis and Encephalitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 New Jersey Reportable Communicable Disease Report (January 3, 2016 to December 31, 2016) (Excl

10:34 Friday, June 30, 2017 1 2016 New Jersey Reportable Communicable Disease Report (January 3, 2016 to December 31, 2016) (excl. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis) (Refer to Technical Notes for Reporting Criteria) Case Jurisdiction Disease Counts STATE TOTAL AMOEBIASIS 98 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - CUTANEOUS 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - INHALATION 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - INTESTINAL 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - OROPHARYNGEAL 0 STATE TOTAL BABESIOSIS 174 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - FOODBORNE 0 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - INFANT 10 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - OTHER, UNSPECIFIED 0 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - WOUND 1 STATE TOTAL BRUCELLOSIS 1 STATE TOTAL CALIFORNIA ENCEPHALITIS(CE) 0 STATE TOTAL CAMPYLOBACTERIOSIS 1907 STATE TOTAL CHIKUNGUNYA 11 STATE TOTAL CHOLERA - O1 0 STATE TOTAL CHOLERA - O139 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE 4 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - FAMILIAL 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - IATROGENIC 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - NEW VARIANT 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - SPORADIC 2 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - UNKNOWN 1 STATE TOTAL CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS 198 STATE TOTAL CYCLOSPORIASIS 29 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - DENGUE 43 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - DENGUE-LIKE ILLNESS 3 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - SEVERE DENGUE 4 STATE TOTAL DIPHTHERIA 0 STATE TOTAL EASTERN EQUINE ENCEPHALITIS(EEE) 1 STATE TOTAL EBOLA 0 STATE TOTAL EHRLICHIOSIS/ANAPLASMOSIS - ANAPLASMA PHAGOCYTOPHILUM (PREVIOUSLY HGE) 109 STATE TOTAL EHRLICHIOSIS/ANAPLASMOSIS - EHRLICHIA CHAFFEENSIS (PREVIOUSLY -

Joint Statement on Insect Repellents by EPA And

Joint Statement on Insect Repellents from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention July 17, 2014 The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are recommending that the public use insect repellents and take other precautions to avoid biting insects that carry serious diseases. The incidence of these diseases is on the rise. This joint statement discusses diseases that are transmitted by ticks and mosquitoes, the role of government in vector control and disease prevention, the history of repellents, how to use repellents as part of an integrated control program, and how to select and use a repellent. Introduction and Purpose CDC and EPA developed this joint statement to promote awareness of repellents and to highlight the effectiveness of repellents in preventing mosquito and tick bites. The agencies believe that promoting the use of repellents may reduce the impact of diseases and nuisance effects caused by these pests. Vector-borne diseases, such as those transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, are among the world's leading causes of illness and death today. A wide variety of arthropods, including mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, black flies, sand flies, horse flies, stable flies, kissing bugs, lice and mites, feed on human blood. Among these, mosquitoes and ticks transmit some of the most serious vector- borne diseases both globally and within the United States. Diseases Transmitted by Mosquitoes and Ticks Mosquito-transmitted West Nile virus caused over 36,000 disease cases and 1,500 deaths in the United States between 1999 and 2012 (CDC, 2012). Mosquitoes also transmit other viruses that cause severe disease in the United States, including La Crosse encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis and dengue. -

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue

2019 Science & Discovery Webinar Series ME/CFS in the Era of the Human Microbiome: Persistent Pathogens Drive Chronic Symptoms by Interfering With Host Metabolism, Gene Expression, and Immunity with Amy Proal, Ph.D. November 14, 2019 | 1:00 PM Eastern www.SolveME.org About Our Webinars • Welcome to the 2019 Webinar Series! • The audience is muted; use the question box to send us questions. Dr. Proal will address as many questions as time permits at the end of the webinar • Webinars are recorded and the recording is made available on our YouTube channel http://youtube.com/SolveCFS • The Solve ME/CFS Initiative does not provide medical advice www.SolveCFS.org 2019 Science & Discovery Webinar Series ME/CFS in the Era of the Human Microbiome: Persistent Pathogens Drive Chronic Symptoms by Interfering With Host Metabolism, Gene Expression, and Immunity with Amy Proal, Ph.D. November 14, 2019 | 1:00 PM Eastern www.SolveME.org Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in the Era of the Human Microbiome: Persistent Pathogens Drive Chronic Symptoms by Interfering With Host Metabolism, Gene Expression, and Immunity Amy Proal, Autoimmunity Research Foundation/PolyBio Millions of patients across the globe are suffering with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS) Currently there is no one disease-specific biomarker and severely ill patients are often wheelchair dependent, bedridden and unable to perform basic tasks of work or daily living. #millionsmissing Myalgic Encephalomeylitis (ME) = swelling of the brain • Unrelenting fatigue that does -

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

TABLE OF CONTENTS AFRICAN TICK BITE FEVER .........................................................................................3 AMEBIASIS .....................................................................................................................4 ANTHRAX .......................................................................................................................5 ASEPTIC MENINGITIS ...................................................................................................6 BACTERIAL MENINGITIS, OTHER ................................................................................7 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE .............................................................................................8 BOTULISM, INFANT .......................................................................................................9 BOTULISM, WOUND .................................................................................................... 10 BOTULISM, OTHER ...................................................................................................... 11 BRUCELLOSIS ............................................................................................................. 12 CAMPYLOBACTERIOSIS ............................................................................................. 13 CHANCROID ................................................................................................................. 14 CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS INFECTION ................................................................. -

African Meningitis Belt

WHO/EMC/BAC/98.3 Control of epidemic meningococcal disease. WHO practical guidelines. 2nd edition World Health Organization Emerging and other Communicable Diseases, Surveillance and Control This document has been downloaded from the WHO/EMC Web site. The original cover pages and lists of participants are not included. See http://www.who.int/emc for more information. © World Health Organization This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale nor for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. The mention of specific companies or specific manufacturers' products does no imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................... i PREFACE ..................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 1 1. MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM ........................................................3 1.1 REVIEW OF EPIDEMICS SINCE THE 1970S .......................................................................................... 3 Geographical distribution -

Seizures in Encephalitis

Neurology Asia 2008; 13 : 1 – 13 REVIEW ARTICLES Seizures in encephalitis Usha Kant Misra DM, *C T Tan MD, Jayantee Kalita DM Department of Neurology, Sanjay Gandhi PGIMS, Lucknow, India; *Department of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract A large number of viruses can result in encephalitis. However, certain viruses are more prevalent in certain geographical regions. For example, Japanese encephalitis (JE) and dengue in South East Asia and West Nile in Middle East whereas Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) occurs all over the world without any seasonal or regional variation. Encephalitis can result in acute symptomatic seizures and remote symptomatic epilepsy. Risk of seizures after 20 years is 22% following encephalitis and 3% after meningitis with early seizures. Amongst the viruses, HSE is associated with most frequent and severe epilepsy. Seizures may be presenting feature in 50% because of involvement of highly epileptogenic frontotemporal cortex. Presence of seizures in HSE is associated with poor prognosis. HSE can also result in chronic and relapsing form of encephalitis and may be an aetiology factor in drug resistant epilepsy. Amongst the Flaviviruses, Japanese encephalitis is the most common and is associated with seizures especially in children. The frequency of seizures in JE is reported to be 6.9% to 46%. Associated neurocysticercosis in JE patients may aggravate the frequency and severity of seizures. Other flaviviruses such as equine, St Louis, and West Nile encephalitis can also produce seizures. In Nipah encephalitis, seizures are commoner in relapsed and late-onset encephalitis as compared to acute encephalitis (50% vs 24%). Other viruses like measles, varicella, mumps, influenza and enteroviruses may result in encephalitis and seizures. -

Summer Safety Guide C L I N T O N C O U N T Y H E a L T H D E P a R T M E N T

SUMMER SAFETY GUIDE C L I N T O N C O U N T Y H E A L T H D E P A R T M E N T S U M M E R 2 0 1 7 WHAT'S INSIDE... 2 7 W H A T ' S B I T I N G Y O U ? P R O T E C T Y O U R H O M E 3 8-9 M O S Q U I T O E S A N I M A L S A N D R A B I E S 4-5 10 T I C K S A N D L Y M E D I S E A S E B E D B U G S 6 11-12 P R O T E C T Y O U R S E L F S U N A N D W A T E R S A F E T Y WHAT'S BITING YOU? P R E V E N T I O N I S Y O U R B E S T D E F E N S E SUMMER HAS ARRIVED! THAT Mosquitoes West Nile virus (WNV) and Eastern MEANS SUN AND FUN, BUT IT equine encephalitis (EEE) are the most common diseases transmitted IS ALSO THE TIME OF YEAR Animals by local mosquitoes. There are no Wildlife is part of the beauty of our WHEN PEOPLE ARE MOST human vaccines for these diseases, Adirondack region, but animals are but there are simple steps you can best viewed from afar. -

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and the Spectrum of JC Virus-Related Disease

REVIEWS Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and the spectrum of JC virus- related disease Irene Cortese 1 ✉ , Daniel S. Reich 2 and Avindra Nath3 Abstract | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a devastating CNS infection caused by JC virus (JCV), a polyomavirus that commonly establishes persistent, asymptomatic infection in the general population. Emerging evidence that PML can be ameliorated with novel immunotherapeutic approaches calls for reassessment of PML pathophysiology and clinical course. PML results from JCV reactivation in the setting of impaired cellular immunity, and no antiviral therapies are available, so survival depends on reversal of the underlying immunosuppression. Antiretroviral therapies greatly reduce the risk of HIV-related PML, but many modern treatments for cancers, organ transplantation and chronic inflammatory disease cause immunosuppression that can be difficult to reverse. These treatments — most notably natalizumab for multiple sclerosis — have led to a surge of iatrogenic PML. The spectrum of presentations of JCV- related disease has evolved over time and may challenge current diagnostic criteria. Immunotherapeutic interventions, such as use of checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive T cell transfer, have shown promise but caution is needed in the management of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an exuberant immune response that can contribute to morbidity and death. Many people who survive PML are left with neurological sequelae and some with persistent, low-level viral replication in the CNS. As the number of people who survive PML increases, this lack of viral clearance could create challenges in the subsequent management of some underlying diseases. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is for multiple sclerosis. Taken together, HIV, lymphopro- a rare, debilitating and often fatal disease of the CNS liferative disease and multiple sclerosis account for the caused by JC virus (JCV). -

Outbreak of Powassan Encephalitis Maine and Vermont, 1999-2001

FROM THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION nal fluid (CSF) contained 40 white blood Her clinical examination showed agita- Outbreak of cells (WBCs)/mm3 (normal: Ͻ4/mm3) tion without confusion, ataxia, bilat- (87% lymphocytes) with elevated pro- eral lateral gaze palsy, and dysarthria. Powassan tein (96 mg/dL; normal: 20-50 mg/dL). CSF contained 148 WBCs/mm3 (46% Encephalitis— Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) neutrophils, 40% lymphocytes). Dur- revealed parietal changes consistent with ing hospitalization, she developed al- Maine and Vermont, microvascular ischemia or demyelinat- tered mental status, generalized muscle 1999-2001 ing disease. No causes for his apparent weakness, and complete ophthalmople- stroke were found. After 22 days of hos- gia. An electroencephalogram (EEG) in- MMWR. 2001;50:761-764 pitalization, he was discharged to a reha- dicated diffuse encephalitis, and a MRI bilitation facility. Nearly 3 months after showed bilateral temporal lobe abnor- POWASSAN (POW) VIRUS, A NORTH symptom onset, he remains in the facil- malities consistent with microvascular American tickborne flavivirus related to ity and is unable to move his left arm or ischemia or demyelinating disease. Af- the Eastern Hemisphere’s tickborne en- leg. Serum specimens and CSF col- ter 13 days, she was transferred to a re- cephalitis viruses,1 was first isolated from lected 3 days after hospitalization habilitation facility where she re- a patient with encephalitis in 1958.1,2 revealed POW virus-specific IgM; neu- mained for 2 months. Nine months after During 1958-1998, 27 human POW en- tralizing antibody (1:640 titer) also was onset of symptoms, she was walking and cephalitis cases were reported from found in serum specimens. -

Encephalitis Fact Sheet

Encephalitis Fact Sheet What is encephalitis? Encephalitis is an inflammation (irritation and swelling) of the brain tissue. It can occur as a primary illness or as a result of another illness elsewhere in the body. Frequently caused by an infection with a virus, encephalitis can be mild or severe, but severe cases are rare. Who gets encephalitis? Anyone can get encephalitis, but young children, older adults, and persons with weakened immune systems are more at risk. How is encephalitis spread? Primary encephalitis occurs when a virus directly infects the brain. Viruses that are carried by infected mosquitoes and ticks can cause primary encephalitis. Other viruses can cause an illness and then encephalitis can develop as a complication of the viral illness. When encephalitis develops after another infection, it is called post-infectious encephalitis. Post-infectious encephalitis most commonly follows a bout of chickenpox, mumps, or measles. What are the symptoms of encephalitis? Encephalitis frequently causes headache, fever, confused thinking, seizures, or problems with vision, speech, or movement. Infants and young children might have nausea, vomiting, body stiffness, constant crying, and poor feeding. How soon after exposure do symptoms appear? Encephalitis can occur within two to three weeks after a viral illness. Symptoms begin within a few days to one or two weeks after the bite from an infected mosquito. How is encephalitis diagnosed? Medical evaluation and special tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis. Anyone with a severe headache, fever, and altered mental status should seek medical care immediately. What is the treatment for encephalitis? Doctors might prescribe antiviral drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs, or other treatments for the symptoms as needed. -

Meningitis/Encephalitis Pathogen Panel

Meningitis/Encephalitis Pathogen Panel The list of pathogens which can potentially cause meningitis, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis is broad. Early effective therapy for both bacterial and certain viral pathogens has been associated with improved outcomes. Patients whose history, exam, and/or imaging suggests one of these conditions should have a lumber puncture performed with appropriate diagnostic testing including a cell count with differential, protein, and glucose. Additional tests to consider include bacterial culture, cryptococcal antigen testing, fungal cultures, cultures for acid fast bacilli and/or the new Meningitis/Encephalitis Pathogen Panel. Nebraska Medicine has recently introduced a new FDA-approved test called the Meningitis/Encephalitis Pathogen Panel (MEPP). This test uses a nested multiplex PCR-approach to amplify DNA targets directly from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with signs and symptoms of meningitis or encephalitis. It is able to detect a variety of common bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens (Table 1). Table 1: Pathogens Detected by Meningitis/Encephalitis Pathogen Panel Bacteria Viruses Yeast Gram-negative Cytomegalovirus Cryptococcus Escherichia coli K1 Enterovirus neoformans/gattii Haemophilus influenzae Herpes simplex virus 1 Neisseria meningitidis Herpes simplex virus 2 Gram-positive Human herpesvirus 6 Listeria monocytogenes Human parechovirus Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Strep) Varicella zoster virus (VZV) Streptococcus pneumoniae This test is sensitive and very specific (see Supplementary Table 1 for complete detail), and should only be performed in patients where CNS infection is being seriously considered. Previous studies have shown that using clinical and CSF criteria to determine when to perform PCR testing is unlikely to miss clinically significant results and is highly cost-effective.1-3 For example Wilen, et al.3 restricted herpes virus and enterovirus PCR testing to patients who were: age <2 years, immunosuppressed, or who had >10 WBCs/µl. -

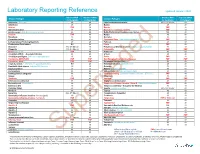

Laboratory Reporting Reference Updated January 2020

Laboratory Reporting Reference Updated January 2020 Report to MOH Report to CMOH Report to MOH Report to CMOH Disease / Pathogen Disease / Pathogen (or Designate) (or Designate) (or Designate) (or Designate) Aeromonas (Stool only) 48 48 Lymphogranuloma Venereum 48 to STI Director 48 Amoebiasis 48 48 Malaria 48 48 Anthrax FMP 48 Measles FMP 48 Arboviral Infections1 48 48 Meningococcal Disease, Invasive FMP 48 Bacillus cereus (Only stool or implicated food) 48 48 Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus N/A 48 Botulism FMP 48 Mumps 48 48 Brucellosis 48 48 Norovirus 48 48 Campylobacteriosis 48 48 Paratyphoid Fever (Salmonella paratyphi A, B or C) FMP 48 Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms 48 48 Pertussis 48 48 Cerebrospinal Fluid Isolates N/A 48 Plague FMP 48 Chancroid 48 to STI Director 48 Pneumococcal Disease, Invasive (Streptococcus pneumoniae) 48 48 Chlamydia 48 to STI Director 48 Poliomyelitis FMP FMP Cholera (O1, O139) FMP 48 Psittacosis 48 48 Clostridium difficile – Associated Infection 48 48 Q fever 48 48 Clostridium perfringens (Only stool or implicated food) 48 48 Rabies FMP 48 Coronavirus, MERS/SARS FMP FMP Rare/Emerging Communicable Diseases2 FMP FMP Coronavirus, Novel FMP FMP Respiratory Syncytial Virus 48 48 Corynebacterium (C. Ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) N/A 48 Rickettsial Infections (Spotted Fevers) 48 48 Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Includes 14-3-3 protein) 48 48 Rotavirus 48 48 Cryptosporidiosis 48 48 Rubella (Includes congenital) 48 48 Cyclosporiasis 48 48 Salmonellosis (Excludes paratyphi & typhi) 48 48 Cytomegalovirus,