Eclipsed Visions Esiaba Irobi Interviewed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Admi

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: OSUAGWU, Linus Chukwunenye. Status: Professor & Former Vice Chancellor. Specialization: Business Administration/Marketing . Nationality: Nigerian. State of Origin: Imo State of Nigeria (Ihitte-Uboma LGA). Marital status: Married (with two children: 23 years; and 9 years). Contact address: School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria,Yola, Adamawa State, Nigeria; Tel: +2348033036440; +2349033069657 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Skype ID: linus.osuagwu; Twitter: @LinusOsuagwu Website: www.aun.edu.ng SCHOOLS ATTENDED WITH DATES: 1. Comm. Sec. School, Onicha Uboma, Ihitte/Uboma, Imo State, Nigeria (1975 - 1981). 2. Federal University of Technology Owerri, Nigeria, (1982 - 1987). 3. University of Lagos, Nigeria (1988 - 1989; 1990 - 1997). ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: PhD Business Administration/Marketing (with Distinction), University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1998). M.Sc. Business Administration/Marketing, University of Lagos, Nigeria, (1990). B.Sc. Tech., Second Class Upper Division, in Management Technology (Maritime), Federal University of Technology Owerri (FUTO), Nigeria (1987). 1 WORKING EXPERIENCE: 1. Vice Chancellor, Eastern Palm University, Ogboko, Imo State, Nigeria (2017-2018). 2. Professor of Marketing, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2008-Date). 3. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Institutional Review Boar (IRB), American University of Nigeria Yola (2008-Date). 4. Professor of Marketing & Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria, Yola (May 2013-May 2015). 4. Professor of Marketing & Acting Dean, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (January 2013-May 2013) . 5. Professor of Marketing & Chair of Business Administration, Department of Business Administration, School of Business & Entrepreneurship, American University of Nigeria (2008-2013). 6. -

Imperatives of Entrepreneurship Education Amongst Library And

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln January 2020 Imperatives of Entrepreneurship Education Amongst Library and Information Science Undergraduate in Nigeria: The Case Study of LIS Undergraduates in South-East and South-South Geopolitical Zones of Nigeria Nneka C. Agim Federal University of Technology, Owerri, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Agim, Nneka C., "Imperatives of Entrepreneurship Education Amongst Library and Information Science Undergraduate in Nigeria: The Case Study of LIS Undergraduates in South-East and South-South Geopolitical Zones of Nigeria" (2020). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 3907. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/3907 Imperatives of Entrepreneurship Education Amongst Library and Information Science Undergraduate in Nigeria: The Case Study of LIS Undergraduates in South-East and South-South Geopolitical Zones of Nigeria Agim, Nneka Chinaemerem University Library Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Entrepreneurship education and its training is an important skill oriented education with prospects of creating self employment amongst students upon graduation and national development. Specifically, to be examined in this study are the available entrepreneurial courses in the curricular of library and information schools in both South-East and South-South Geopolitical zones of Nigeria, to determine the benefit of entrepreneurial courses for undergrad uates in library schools in South- East and South-South Geopolitical zones of Nigeria and to examine the factors affecting entrepreneurship education in library schools in South-East and South-South Geopolitical zone of Nigeria. -

Determination of Aquifer Potentials of Abia State University Uturu (ABSU

Journal of Geology and Mining Research Vol. 3(10), pp. 251-264, October 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JGMR ISSN 2006-9766 ©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Determination of aquifer potentials of Abia State University, Uturu (ABSU) and its environs using vertical electrical sounding (VES) M. U. Igboekwe* and Akpan, C. B. Department of Physics, Micheal Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike, P. M.B. 7267 Umuahia, Nigeria. Accepted 23 October, 2010 Resistivity soundings have been carried out around the Abia State University, Uturu (ABSU) and its environs, using the Schlumberger configuration. The major aim is to delineate potential aquifer zones for regional groundwater harvesting and further development. The geologic formations in the study area consist of a sequence of underlying Lower Coal Measures (Mamu), the Ajali formation and the upper coal measures (Nsukka formation). The Ajali formation, which is the most predominant in the sequence, consists of false-bedded poorly sorted sandstones. Twenty (20) vertical electrical soundings (VES) are taken with AB/2 = 500 m. The geoelectrical data analysis indicates the heterogenous nature of the aquifer with resistivity range between 2291.8 to 100,000 m. Assuming a homogeneous sandy aquifer, the average hydraulic conductivity (k) and transmissivity (Tr) distribution within the study area, are found to be 8.12 m/day and 1154.2 m2/day respectively. Based on these results, potential aquifer zones have been identified between Ugba junction (Uturu) and 200 m southeastward along Isukwuato- ABSU road. Key words: Abia State University Uturu (ABSU), aquifer, Schlumberger, VES, resistivity, transmissivity. INTRODUCTION Unlike surface water resources, the evaluation of population. -

4.Leonard Nwosu and Doris Ndubueze

Human Journals Research Article February 2017 Vol.:5, Issue:4 © All rights are reserved by Leonard Nwosu et al. Geoelectric Investigation of Water Table Variation with Surface Elevation for Mapping Drill Depths for Groundwater Exploitation in Owerri Metropolis, Imo State, Nigeria. Keywords: Water table, surface elevation, drill depth, resistivity, groundwater. ABSTRACT A total of 20 Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) were *1Leonard Nwosu and 2Doris Ndubueze carried out in different locations in Owerri Metropolis, Imo state of Nigeria in order to investigate water table variation 1. Department of Physics University of Port with surface elevation for assessment of groundwater Harcourt, Nigeria. potential. Field data were acquired using the OHMEGA-500 resistivity meter and accessories. The Schlumberger electrode 2. Department of Physics Michael Okpara University configuration with maximum electrode spread of 700m was adopted. At each VES point, coordinates and elevations were of Agriculture Umudike, Nigeria. measured using the Global Positioning System (GPS). The field data were interpreted using the Advanced Geosciences Submission: 2 February 2017 Incorporation (AGI) 1D software and the Schlumberger automatic analysis version. The results revealed that the area Accepted: 7 February 2017 is underlain by multi geoelectric layers with about 6 to 9 Published: 25 February 2017 lithological units identified. The aquiferous layer is composed mainly of fine sand and sandstone units with low resistivity values recorded in Owerri West Area. The resistivity values ranged from 0.6Ωm to 1100.8Ωm. The depth to the water table varied across the area with surface elevation and ranged from 16.80m to 85.6m. Similarly, the aquifer thickness www.ijsrm.humanjournals.com ranged from 13.23m to 111.56m. -

Senate Building

PROPOSED SENATE BUILDING FOR IMO STATE UNIVERSITY, OWERRI 1: ,Enhancing higher productivity in administration through effective space planning) BY FAK'ERE, ALEXANDER ADEYEMI ARCI0414333 ' A THESIS SUBMIITED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF TECHNOLOGY (M. TECH.) IN ARCHITECTURE, FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AKURE, ONDO ,STATE, NIGERIA JULY, 2006. , . -- -------- ABSTRACT The need for a befitting central Administrative building for any institution of higher learning and Imo State University in particular cannot be overemphasized. This is evident in the situation experienced presently at the Imo State University where conversion of mere office blocks to University administrative building is not enhancing productivity in administration and hence, increases fatigue. The student carried out this study in order to address this problem of lack of a central administrative center in Imo State University, Owerri, as the existing structures are far apart and not easy to locate by visitors. This situation from the ll:formation gathered, was as a result of the relocation of the university form the old site to the present site. This present site was designed for Federal Government Girls' College, Owerri. The university had to relocate to this site when it was displaced from the former site at Uturu, Okigwe in 1991 when Abia State was created. The methods used by the student to carry out the research were interviews with some of the senior administrative staff of the university, data collection from some published and unpublished materials and the internet, and case studies of existing administrative buildings of some universities. -

Percentage of Special Needs Students

Percentage of special needs students S/N University % with special needs 1. Abia State University, Uturu 4.00 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi 0.00 3. Achievers University, Owo 0.00 4. Adamawa State University Mubi 0.50 5. Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba 0.08 6. Adeleke University, Ede 0.03 7. Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti - Ekiti State 8. African University of Science & Technology, Abuja 0.93 9. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 0.10 10. Ajayi Crowther University, Ibadan 11. Akwa Ibom State University, Ikot Akpaden 0.00 12. Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike, Ikwo 0.01 13. Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin 0.00 14. Al-Qalam University, Katsina 0.05 15. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 0.03 16. American University of Nigeria, Yola 0.00 17. Anchor University Ayobo Lagos State 0.44 18. Arthur Javis University Akpoyubo Cross River State 0.00 19. Augustine University 0.00 20. Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo 0.12 21. Bayero University, Kano 0.09 22. Baze University 0.48 23. Bells University of Technology, Ota 1.00 24. Benson Idahosa University, Benin City 0.00 25. Benue State University, Makurdi 0.12 26. Bingham University 0.00 27. Bowen University, Iwo 0.12 28. Caleb University, Lagos 0.15 29. Caritas University, Enugu 0.00 30. Chrisland University 0.00 31. Christopher University Mowe 0.00 32. Clifford University Owerrinta Abia State 0.00 33. Coal City University Enugu State 34. Covenant University Ota 0.00 35. Crawford University Igbesa 0.30 36. Crescent University 0.00 37. Cross River State University of Science &Technology, Calabar 0.00 38. -

11 August, 2014 Prof. Alessandro Prinetti, Chair of ISN-CC, Professor

11 August, 2014 Prof. Alessandro Prinetti, Chair of ISN-CC, Professor of Biochemistry Department of Medical Biotechnology and Translational Medicine The Medical School, University of Milano, Italy Dear Prof. Prinetti, REPORT OF 5TH INBR 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEUROSCIENCE CONFERENCE, OWERRI, NIGERIA The 5th biennial conference of the Institute of Neuroscience and Biomedical Research (INBR) held in Global Towers Hotels and Tourism Ltd, Owerri, Nigeria, from 28th to 31st July 20104, and dwelt on the theme “Nervous System in Health and Disease: Nutritional Supplements”. The Meeting was very successful in many respects. It started on Wednesday, 28th July 2014, with a vey scintillating pre-Conference Workshop held in the Histology Auditorium of the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology of the Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria. The interaction centered on techniques of writing research papers, neuroimaging with emphasis on PET techniques, and neurobehavioural tests. Resource persons were Peter Brust (Germany), Polycarp Nwoha, Meashack Ijomone (Nigeria). Participants were diverse, undergraduate students, graduate students, science teachers, researchers in universities and other higher institutions. There was general appreciation of all the information provided by the resource persons, including the round table that provided open lively and spirited discussion. On Tuesday the 29th July, the Conference proper began with the 1st plenary lectrure “The Light Theory of Brain Function and Gender Complimentarity”delivered by Academician Dr. Philip Njemanze; this was followed by discussions. The next plenary lecture “Health Hazards of Polluted Environment” was delivered by Professor Polycarp Nwoha, and thereafter discussions. The third plenary lecture” Onchocerciasis and Nervous System In Africa: The Present Appraisal” was delivered by Professor BEB Nwoke, the former Vice-Chancellor, Imo State university, followed by discussions. -

Usein Imo State, Nigeria

Nigerian Agricultural Policy Research Journal. Volume 1, Issue 1, 2016. http://aprnetworkng.org Usein Imo State, Nigeria A. O. Ejiogu and E.C. Onyenoneke Department of Agricultural Economics, Imo State University, Owerri Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract child labour use in Imo State of Nigeria. Specifically, the study determined the effect of the socioeconomic factors that -stage random sampling was employed in choosing the respondents for this study. One local government area (LGA) in each of the three agricultural zones was purposively selected for the study based on suitability for rice production. Communities which are known for rice production were purposively selected from the selected LGAs. The list of rice farmers in each chosen community was obtained from Imo ADP. The list formed the sampling frame from which the respondent rice farmers were selected using random sampling procedure. Thirty rice farmers were selected from each community, making a sample size of 90.Data was analyzed with binary logistic regression technique. The variables namely gender, marital ge and educational attainment were significant at 1% level. Furthermore, gender, marital status, family size, farm size, educational attainment and rice farm experience were statistically significant variables with negatively effect on the use of child labour. Age though statistically significant, had positive effect on the use of child labour. Efforts aimed at curbing the adverse effects of child labour should to all intents and purposes be fundamentally targeted at the predisposing socioeconomic factors. Key Words: Rice farmers, labour use, socioeconomic, Imo State 1. Introduction Rice is a staple food for many people in Imo rice production in Nigeria has been identified to State, Nigeria. -

265 Austine O. Nnaji Federal University of Technology Owerri

e-Review of Tourism Research (eRTR), Vol. 9, No. 6, 2011 http://ertr.tamu.edu Austine O. Nnaji Federal University of Technology Owerri P. A. Igbojiekwe and C. C. Nnaji Imo State University An Assessment of Developmental Potential of Oguta Lake as a Tourist Destination Recent efforts by the Imo State government of Nigeria to generate income through tourism identified Oguta Blue Lake as a potentially homogeneous region for tourism development. This understanding is expanded through a study of the bio-physical nature of the lake to ascertain its socio-economic viability for tourism development. Sustainability and diversity attributes of the lake were a major focus. Utilizing empirical data generated from structured questionnaires and field surveys, analysis was performed employing ANOVA statistic and simple percentages to reveal the lake’s potential as a tourist destination. The paper also projects rapid urbanization of the region powered by tourism while recommending massive infrastructural development of the lake to accommodate the anticipated population surge. Key words: Tourism Development, Outdoor Recreation, Oguta Lake, watershed management, Recreation, Hospitality industry Austine O. Nnaji Department of Environmental Technology Federal University of Technology Owerri Nigeria Phone: 07062678890 Email: [email protected] P. A. Igbojiekwe and C. C. Nnaji Dept of Hospitality and Tourism Management Imo State University, Owerri Nigeria Dr. Austine O. Nnaji is a senior Lecturer at Federal University of Technology Owerri, Nigeria, while an adjunct lecturer at Imo State University. His has a Ph.D in Geography from University of Florida, Gainesville (1999), an M. Sc from Florida A&M University, Tallahasse (1993) and a B. -

The Effect of Strikes on Students Who Attended Imo State University, Nigeria, from 2012 -2017: a Phenomenological Study

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Department of Conflict Resolution Studies CAHSS Theses, Dissertations, and Applied Theses and Dissertations Clinical Projects 2020 The Effect of Strikes on Students Who Attended Imo State University, Nigeria, from 2012 -2017: A Phenomenological Study Innocent Okechukwu Ntiasagwe Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss_dcar_etd Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Share Feedback About This Item This Dissertation is brought to you by the CAHSS Theses, Dissertations, and Applied Clinical Projects at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Conflict Resolution Studies Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effect of Strikes on Students Who Attended Imo State University, Nigeria, from 2012 -2017: A Phenomenological Study by Innocent Ntiasagwe A Dissertation Presented to the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences of Nova Southeastern University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Nova Southeastern University 2020 Copyright © by Innocent Ntiasagwe June 2020 Nova Southeastern University College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences This dissertation was submitted by Innocent Ntiasagwe under the direction of the chair of the dissertation committee listed below. It was submitted to the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences and approved in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Conflict Analysis and Resolution at Nova Southeastern University. Approved: __June 12, 2020______ _Elena P, Bastidas R___ Date of Defense Elena Bastidas, Ph.D. Chair _Robin Cooper_________ Robin Cooper, Ph.D. Judith McKay___________ Judith McKay, J.D., Ph.D. -

Funding Teacher Education: a Catalyst for Enhancing the Universal Basic Education in IMO State of Nigeria Martin Okoro Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) 2011 Funding Teacher Education: a Catalyst for Enhancing the Universal Basic Education in IMO State of Nigeria Martin Okoro Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Okoro, Martin, "Funding Teacher Education: a Catalyst for Enhancing the Universal Basic Education in IMO State of Nigeria" (2011). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 436. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/436 FUNDING TEACHER EDUCATION: A CATALYST FOR ENHANCING THE UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATIBN IN IN0 STATE OF NIGERIA BY MARTIN OKORO Dissertation Committee Elaine Walker, Ph. D., Mentor Daniel Gutmore, Ph.D. Joseph Stetar, Ph.D. Maurice Ene, Ph.D Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor Of Education Seton Hall University SETON HALL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN SERVICES OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES APPROVAL FOR SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE Doctoral Candidate, Martin Okoro, has successfully defended and made the required modifications to the text of the doctoral dissertation for the Ed.D. during this Fall Semester 2010. DISSERTATION COMMITTEE (please sign and date beside your name) Mentor: Dr. Elaine Walker / / " Committee Member: Dr. Daniel Gutmore Committee Member: Dr. Joseph Stetar Y Committee Memb Dr. Maurice Ene External Reader: The mentor and any other committee members who uiish to review revisions will sign and date this document only when revisions have been completed. Please return this form to the Office of Graduate Studies, where it will be placed in the candidate's file and submit a copy with your final dissertation to be bound as page number two. -

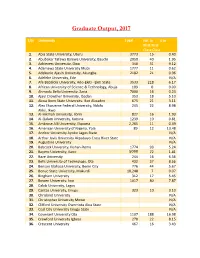

Graduate Output, 2017

Graduate Output, 2017 S/N University Total No. In % in First First Class Class 1. Abia State University, Uturu 3773 15 0.40 2. Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi 2050 40 1.95 3. Achievers University, Owo 340 31 9.12 4. Adamawa State University Mubi 1777 11 0.62 5. Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba 2182 21 0.96 6. Adeleke University, Ede N/A 7. Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti - Ekiti State 3533 218 6.17 8. African University of Science & Technology, Abuja 109 0 0.00 9. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria 7000 16 0.23 10. Ajayi Crowther University, Ibadan 353 18 5.10 11. Akwa Ibom State University, Ikot Akpaden 675 21 3.11 12. Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu 245 22 8.98 Alike, Ikwo 13. Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin 827 16 1.93 14. Al-Qalam University, Katsina 1239 10 0.81 15. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 2,265 11 0.49 16. American University of Nigeria, Yola 89 12 13.48 17. Anchor University Ayobo Lagos State N/A 18. Arthur Javis University Akpabuyo Cross River State N/A 19. Augustine University N/A 20. Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo 1774 93 5.24 21. Bayero University, Kano 5098 72 1.41 22. Baze University 244 16 6.56 23. Bells University of Technology, Ota 432 37 8.56 24. Benson Idahosa University, Benin City 776 44 5.67 25. Benue State University, Makurdi 10,248 7 0.07 26. Bingham University 312 17 5.45 27. Bowen University, Iwo 1017 80 7.87 28.