The North Borneo Claim As State Policy 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil, Gas & Energy Sector

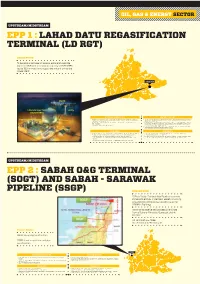

OIL, GAS & ENERGY SECTOR UPSTREAM/MIDSTREAM EPP 1 : LAHAD DATU REGASIFICATION TERMINAL (LD RGT) DESCRIPTION To develop a facilities to receive, store and vaporize imported LNG with a maximum capacity of 0.76 MTPA (up to 100 mmscfd) and supply the natural gas to the Power Plant lahad datu Berth LNG Storage Tank Jetty (0.76 MTPA) Key outcomes of the EPP / KPIs What needs to be done? Vaporization Station • Availability of natural gas supply at east coast of Sabah including Sandakan, Lahad Datu • Construction period of LNG Storage Tank which is the critical path of the project (normally and Tawau (also along the route) will take up to 24 months) • Transfer of technology and knowledge to local manpower and contractors who are involved • Front End phase of a project, where activities are mainly focused towards project planning with this project and contracting/bidding activities for the appointment of Frond End Engineering Design • Spurring the economy along the pipeline Consultant expected in mid-October 2011 • Evaluate and finalize the land lease of the reclaimed land of the proposed site with POIC. • Site Reclamation works is expected to start by Q1 2012 Key Challenges Mitigation Plan • Transporting major equipment and bulk materials from Sandakan to Lahad Datu (~200km) • Improvement of the road condition from Sandakan to Lahad Datu or consider for • Shortage of capable manpower due to simultaneous construction of LD power plant permanent/temporary jetty at Lahad Datu • Available manpower are lack of re-gas terminal construction skills (special) -

Sabah REDD+ Roadmap Is a Guidance to Press Forward the REDD+ Implementation in the State, in Line with the National Development

Study on Economics of River Basin Management for Sustainable Development on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Conservation in Sabah (SDBEC) Final Report Contents P The roject for Develop for roject Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Study .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Detailed Work Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 ing 1.4 Implementation Schedule ............................................................................................. 3 Inclusive 1.5 Expected Outputs ......................................................................................................... 4 Government for for Government Chapter 2 Rural Development and poverty in Sabah ........................................................... 5 2.1 Poverty in Sabah and Malaysia .................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policy and Institution for Rural Development and Poverty Eradication in Sabah ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Issues in the Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation from Perspective of Bangladesh in Corporation City Biodiversity -

Prk Kerusi Parlimen Pasca Pru-14 Di Sabah: P186- Sandakan, P176-Kimanis, P185-Batu Sapi Dan Darurat

Volume 6 Issue 23 (April 2021) PP. 200-214 DOI 10.35631/IJLGC.6230014 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LAW, GOVERNMENT AND COMMUNICATION (IJLGC) www.ijlgc.com PRK KERUSI PARLIMEN PASCA PRU-14 DI SABAH: P186- SANDAKAN, P176-KIMANIS, P185-BATU SAPI DAN DARURAT THE POST GE-14 PARLIAMENTARY SEAT BY-ELECTIONS IN SABAH: P186- SANDAKAN, P176-KIMANIS, P185-BATU SAPI AND THE EMERGENCY Mohd Azri Ibrahim1*, Romzi Ationg2*, Mohd Sohaimi Esa3*, Irma Wani Othman4*, Saifulazry Mokhtar5 & Abang Mohd Razif Abang Muis6 1 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 2 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 3 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 4 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 5 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] 6 Centre for the Promotion of Knowledge and Language Learning, Universiti Malaysia Sabah Email: [email protected] * Corresponding Author Article Info: Abstrak: Article history: Kertas kerja ini mengetengahkan perbincangan tentang pelaksanaan mahupun Received date: 15.01.2021 penangguhan Pilihanraya Kecil (PRK) di Sabah dalam era pasca Pilihanraya Revised date: 15.02.2021 Umum ke-14 (PRU-14) dan kaitannya dengan pelaksanaan Perintah Kawalan Accepted date: 15.03.2021 Pergerakan (PKP) serta darurat. Secara khusus, kertas kerja ini Published date: 30.04.2021 membincangkan secara mendalam pelaksanaan PRK di P186 Sandakan dan To cite this document: P176 Kimanis. -

UK and Colonies

This document was archived on 27 July 2017 UK and Colonies 1. General 1.1 Before 1 January 1949, the principal form of nationality was British subject status, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the Crown's dominions. On and after this date, the main form of nationality was citizenship of the UK and Colonies, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the UK and Colonies. 2. Meaning of the expression 2.1 On 1 January 1949, all the territories within the Crown's dominions came within the UK and Colonies except for the Dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, India, Pakistan and Ceylon (see "DOMINIONS") and Southern Rhodesia, which were identified by s.1(3) of the BNA 1948 as independent Commonwealth countries. Section 32(1) of the 1948 Act defined "colony" as excluding any such country. Also excluded from the UK and Colonies was Southern Ireland, although it was not an independent Commonwealth country. 2.2 For the purposes of the BNA 1948, the UK included Northern Ireland and, as of 10 February 1972, the Island of Rockall, but excluded the Channel Islands and Isle of Man which, under s.32(1), were colonies. 2.3 The significance of a territory which came within the UK and Colonies was, of course, that by virtue of a connection with such a territory a person could become a CUKC. Persons who, prior to 1 January 1949, had become British subjects by birth, naturalisation, annexation or descent as a result of a connection with a territory which, on that date, came within the UK and Colonies were automatically re- classified as CUKCs (s.12(1)-(2)). -

Sabah 90000 Tabika Kemas Kg

Bil Nama Alamat Daerah Dun Parlimen Bil. Kelas LOT 45 BATU 7 LORONG BELIANTAMAN RIMBA 1 KOMPLEKS TABIKA KEMAS TAMAN RIMBAWAN Sandakan Sungai SiBuga Libaran 11 JALAN LABUKSANDAKAN SABAH 90000 TABIKA KEMAS KG. KOBUSAKKAMPUNG KOBUSAK 2 TABIKA KEMAS KOBUSAK Penampang Kapayan Penampang 2 89507 PENAMPANG 3 TABIKA KEMAS KG AMAN JAYA (NKRA) KG AMAN JAYA 91308 SEMPORNA Semporna Senallang Semporna 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI WDT 09 89909 4 TABIKA KEMAS KG. AMBOI Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KAMPUNG PULAU GAYA 88000 Putatan 5 TABIKA KEMAS KG. PULAU GAYA ( NKRA ) Tanjong Aru Putatan 2 KOTA KINABALU (Daerah Kecil) KAMPUNG KERITAN ULU PETI SURAT 1894 89008 6 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG KERITAN ULU Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 7 TABIKA KEMAS ( NKRA ) KG MELIDANG TABIKA KEMAS KG MELIDANG 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 8 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG KUANGOH TABIKA KEMAS KG KUANGOH 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 9 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG MONGITOM JALAN APIN-APIN 89008 KENINGAU Keningau Bingkor Keningau 1 TABIKA KEMAS KG. SINDUNGON WDT 09 89909 10 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) KG. SINDUNGON Tenom Kemabong Tenom 1 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TAMAN MUHIBBAH LORONG 3 LOT 75. 89008 11 TABIKA KEMAS (NKRA) TAMAN MUHIBBAH Keningau Liawan Keningau 1 KENINGAU 12 TABIKA KEMAS ABQORI KG TANJUNG BATU DARAT 91000 Tawau Tawau Tanjong Batu Kalabakan 1 FASA1.NO41 JALAN 1/2 PPMS AGROPOLITAN Banggi (Daerah 13 TABIKA KEMAS AGROPOLITAN Banggi Kudat 1 BANGGIPETI SURAT 89050 KUDAT SABAH 89050 Kecil) 14 TABIKA KEMAS APARTMENT INDAH JAYA BATU 4 TAMAN INDAH JAYA 90000 SANDAKAN Sandakan Elopura Sandakan 2 TABIKA KEMAS ARS LAGUD SEBRANG WDT 09 15 TABIKA KEMAS ARS (A) LAGUD SEBERANG Tenom Melalap Tenom 3 89909 TENOM SABAH 89909 TENOM TABIKA KEMAS KG. -

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 45: 225–235, 2021 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published July 15 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01112 Endang Species Res OPEN ACCESS Hunting pressure is a key contributor to the impending extinction of Bornean wild cattle Penny C. Gardner1,2,3,4, Benoît Goossens1,2,5,6,*, Soffian Bin Abu Bakar5, Michael W. Bruford2,6 1Danau Girang Field Centre, c/o Sabah Wildlife Department, Wisma Muis, 88100 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia 2Organisms and Environment Division, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Sir Martin Evans Building, Museum Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3AX, UK 3School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Environmental and Life Sciences, Life Sciences Building 85, University of Southampton, Highfield Campus, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK 4RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy SG19 2DL, UK 5Sabah Wildlife Department, Wisma Muis, 88100 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia 6Sustainable Places Research Institute, Cardiff University, 33 Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3BA, UK ABSTRACT: Widespread and unregulated hunting of ungulates in Southeast Asia is resulting in population declines and localised extinctions. Increased access to previously remote tropical for- est following logging and changes in land-use facilitates hunting of elusive wild cattle in Borneo, which preferentially select secluded habitat. We collated the first population parameters for the Endangered Bornean banteng Bos javanicus lowi and developed population models to simulate the effect of different hunting offtake rates on survival and the recovery of the population using reintroduced captive-bred individuals. Our findings suggest that the banteng population in Sabah is geographically divided into 4 management units based on connectivity: the Northeast, Sipitang (West), Central and Southeast, which all require active management to prevent further population decline and local extinction. -

The Kimanis By-Election: a Much-Needed Sweet (Manis) Victory for Warisan

ISSUE: 2020 No. 3 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore |16 January 2020 The Kimanis By-election: A Much-needed Sweet (Manis) Victory for Warisan Lee Poh Onn and Kevin Zhang*1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • On 18 January 2020, a by-election will be held for the parliamentary seat of Kimanis in Sabah. The Federal Court has upheld the Election Court's ruling that Anifah Aman's victory in the 14th General Elections (GE14) was nullified by election discrepancies. • This by-election is seen as a referendum on the Warisan state government’s performance over the past 18 months since replacing the Barisan Nasional (BN) after GE14, and the outcome would have some impact on Sabah Chief Minister Shafie Apdal’s standing. Warisan-PH and BN had won an equal number of state seats, but Warisan formed the state government only after the defection of some BN state assemblymen. At the Federal level, the Pakatan Harapan government sorely needs a victory in Kimanis to reverse the trend of by-election defeats it has suffered over the past year. • Warisan began the election contest on a stronger footing but it is shaping up to be a close fight. Both candidates, Warisan’s Karim Bujang and UMNO’s Mohamad Alamin, have strong political experience in Kimanis. • Bread and butter issues matter greatly to Kimanis residents who mostly suffer from low incomes and poor infrastructure. Warisan is on the defensive against the BN’s claims that the state government has failed to bring economic uplift to the area. -

BIMP-EAGA Subregional Programs Power Interconnection

BIMP-EAGA Subregional Programs Power Interconnection 3rd Regional Power Market & Cross Border Interconnections Training 13th -17th November 2017 Quick Facts on BIMP EAGA Subregional Program • Established on 1994 mainly to address socioeconomic development of less developed, marginalized and far-flung areas. • To narrow development gap within and across the sub-region. 2 Quick Facts on BIMP EAGA Subregional Program • Geographically covers: - Entire Brunei Darussalam - 9 Provinces in Kalimantan and Sulawesi, Maluko Islands, Papua in Indonesia - Federal States of Sabah and Sarawak, and the Federal Territory of Labuan in Malaysia - 26 provinces of Mindanao and the Island Province of Palawan in the Philippines 3 BIMP EAGA Subregional Program The BIMP EAGA Subregion 5 BIMP EAGA Institutional Structure 6 BIMP-EAGA Implementation Blueprint Results Framework Goal: To narrow the development gap across & within EAGA member countries as well as across the ASEAN-6 countries Objectives: >Increase Trade >Increase Tourism >Increase Investments Strategic Pillar 1: Strategic Pillar 2: Strategic Pillar 3: Strategic Pillar 4: Connectivity Food Basket Community Based Environment • Infrastructure Ecotourism •Sustainable Development • Food Security • Tourism Products Management of Critical Ecosystems • Air, Sea, & Land • Export Development & tourism Services infrastructure •Climate Change • Sustainable •Clean and Green • Power Livelihood • Community & Interconnection & Production Private Technologies Renewable Energy • Sector •Transboundary issues • ICT Participation • Environment • Trade Facilitation • CBET destination mainstreaming Rolling Pipeline: Programs/Projects/Policy Support/Activities/Events Results Monitoring (Outputs and Outcomes) BRUNEI DARUSSALAM-INDONESIA-MALAYSIA-THE PHILIPPINES EAST ASEAN GROWTH AREA (BIMP-EAGA) Part 2: Energy Cooperation in Subregional Program NO PROJECT TITLE Status 2017 (Include Lead Country) As of Today Activities with milestones 1 Trans Borneo Power Grid: Sarawak- West Kalimantan Power Completed/Commissioned Energized 20 Jan. -

Borneo's New World

Borneo’s New World Newly Discovered Species in the Heart of Borneo Dendrelaphis haasi, a new snake species discovered in 2008 © Gernot Vogel © Gernot WWF’s Heart of Borneo Vision With this report, WWF’s Initiative in support of the Heart of Borneo recognises the work of scientists The equatorial rainforests of the Heart and researchers who have dedicated countless hours to the discovery of of Borneo are conserved and effectively new species in the Heart of Borneo, managed through a network of protected for the world to appreciate and in its areas, productive forests and other wisdom preserve. sustainable land-uses, through cooperation with governments, private sector and civil society. Cover photos: Main / View of Gunung Kinabalu, Sabah © Eric in S F (sic); © A.Shapiro (WWF-US). Based on NASA, Visible Earth, Inset photos from left to right / Rhacophorus belalongensis © Max Dehling; ESRI, 2008 data sources. Dendrobium lohokii © Amos Tan; Dendrelaphis kopsteini © Gernot Vogel. A declaration of support for newly discovered species In February 2007, an historic Declaration to conserve the Heart of Borneo, an area covering 220,000km2 of irreplaceable rainforest on the world’s third largest island, was officially signed between its three governments – Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia and Malaysia. That single ground breaking decision taken by the three through a network of protected areas and responsibly governments to safeguard one of the most biologically managed forests. rich and diverse habitats on earth, was a massive visionary step. Its importance is underlined by the To support the efforts of the three governments, WWF number and diversity of species discovered in the Heart launched a large scale conservation initiative, one that of Borneo since the Declaration was made. -

UK and Colonies 1. General 1.1 Before 1 January 1949

UK and Colonies 1. General 1.1 Before 1 January 1949, the principal form of nationality was British subject status, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the Crown's dominions. On and after this date, the main form of nationality was citizenship of the UK and Colonies, which was obtained by virtue of a connection with a place within the UK and Colonies. 2. Meaning of the expression 2.1 On 1 January 1949, all the territories within the Crown's dominions came within the UK and Colonies except for the Dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Newfoundland, India, Pakistan and Ceylon (see "DOMINIONS") and Southern Rhodesia, which were identified by s.1(3) of the BNA 1948 as independent Commonwealth countries. Section 32(1) of the 1948 Act defined "colony" as excluding any such country. Also excluded from the UK and Colonies was Southern Ireland, although it was not an independent Commonwealth country. 2.2 For the purposes of the BNA 1948, the UK included Northern Ireland and, as of 10 February 1972, the Island of Rockall, but excluded the Channel Islands and Isle of Man which, under s.32(1), were colonies. 2.3 The significance of a territory which came within the UK and Colonies was, of course, that by virtue of a connection with such a territory a person could become a CUKC. Persons who, prior to 1 January 1949, had become British subjects by birth, naturalisation, annexation or descent as a result of a connection with a territory which, on that date, came within the UK and Colonies were automatically re- classified as CUKCs (s.12(1)-(2)). -

Colony of North Borneo Annual Report

«r; • c- 2.^.0- COLONIAL REPORTS North Borneo .-•■■'■ . ■ - - ■ LONDON HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE 1956 1 i Designed, printed and bound by the Technical Staff of the Government Printing Department, North Borneo, 1956 Contents Page PART i Chapter 1 General Review ... ... ... ... 1 PART II Chapter 1 Population ... ... ... ... 9 2 Occupation, Wages and Labour Organisation ... 14 3 Public Finance and Taxation ... ... 20 4 Currency and Banking ... ... ... 27 5 Commerce ... ... ... ... 28 6 Production Land Utilisation and Ownership ... ... 34 Agriculture ... ... ... ... 39 Animal Husbandry ... ... ... 46 Drainage and Irrigation ... .. 48 Forests ... ... ... ... 49 Fisheries ... ... ... ... 57 7 Social Services Education ... ... ... ... 60 Public Health ... ... ... ... 68 Housing and Town Planning ... 74 Social Welfare ... ... ... ... 77 8 Legislation ... ... ... ... 84 9 Justice, Police and Prisons Justice ... ... ... ... 86 Police ... ... ... ... 87 Prisons ... ... ... ... 93 10 Public Utilities and Public Works Public Works Department ... ... 96 Electricity ... ... ... ... 98 Water ... ... ... ... 99 11 Communications Harbours and Shipping ... ... 102 Railways ... ... ... ... 106 Roads ... ... ... ... 109 Road Transport ... ... Ill Air Communications ... ... ... Ill Posts ... ... ... ... 114 Telecommunications ... ... ... 114 12 Government Information Services, Broadcasting, Press and Films ... ... ... 116 13 Geology ... ... ... ... 122 PART III Chapter 1 Geography and Climate ... ... ... 129 2 History History ... ... ... ... 134 List -

No. 10760 UNITED KINGDOM of GREAT BRITAIN and NORTHERN

No. 10760 UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND and FEDERATION OF MALAYA, NORTH BORNEO, SARAWAK and SINGAPORE Agreement relating to Malaysia (with annexes, including the Constitutions of the States of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore, the Malaysia Immigration Bill and the Agreement between the Governments of the Federation of Malaya and Singapore on common market and financial arrangements). Signed at London on 9 July 1963 Agreement amending the above-mentioned Agreement. Signed at Singapore on 28 August 1963 Authentic texts of the Agreement: English and Malay. Authentic text of the annexes: English. Authentic text of the amending Agreement: English. Registered by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on 21 September 1970. United Nations — Treaty Series 1970 AGREEMENT 1 RELATING TO MALAYSIA The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore; Desiring to conclude an agreement relating to Malaysia; Agree as follows: Article I The Colonies of North Borneo and Sarawak and the State of Singapore shall be federated with the existing States of the Federation of Malaya as the States of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore in accordance with the constitutional instruments annexed to this Agreement and the Federation shall thereafter be called " Malaysia ". Article II The Government of the Federation of Malaya will take such steps as may be appropriate and available to them to secure the enactment by the Parliament of the Federation of Malaya of an Act in the form set out in Annex A to this Agreement and that it is brought into operation on 31st August 1963 * (and the date on which the said Act is brought into operation is hereinafter referred to as " Malaysia Day ").