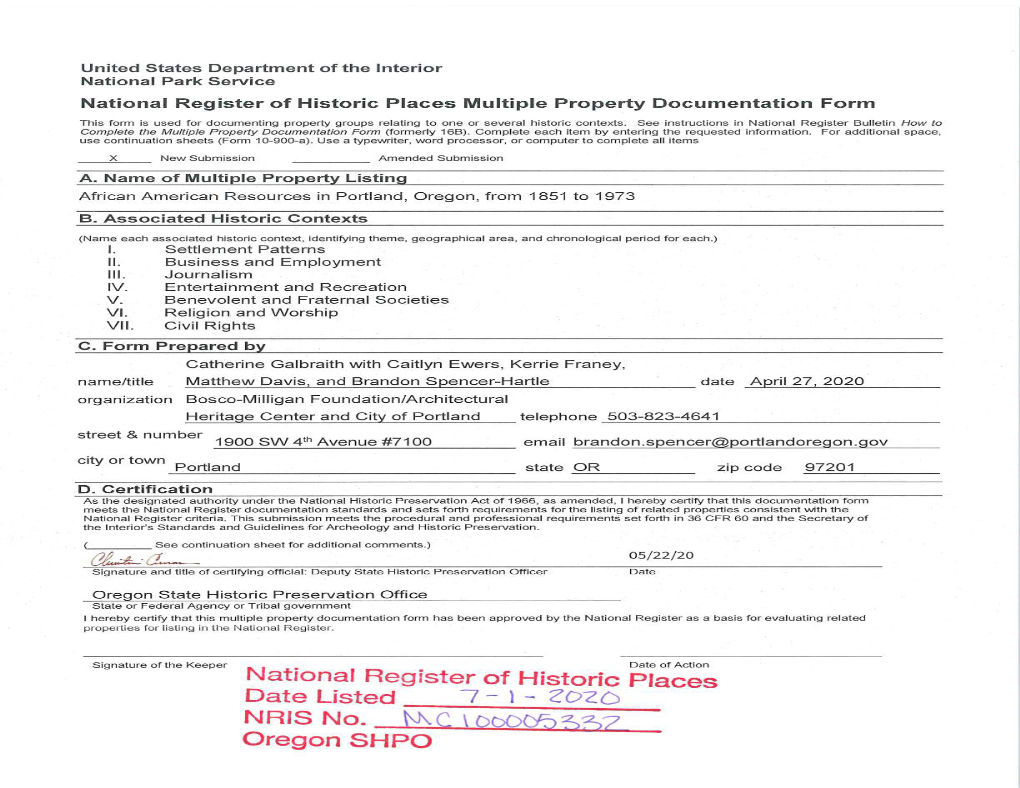

African American Resources in Portland MPD Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Voters' Pamphlet

Washington Elections Division 3700 SW Murray Blvd. Beaverton, OR 97005 County www.co.washington.or.us voters’ pamphlet VOTE-BY-MAIL PRIMARY NOMINATING ELECTION May 20, 2008 To be counted, voted ballots must be in our office by 8:00 pm on May 20, 2008 Washington County Dear Voter: Board of County This pamphlet contains information for several dis- Commissioners tricts and there may be candidates/measures included that are not on your ballot. If you have any questions, Tom Brian, Chair call 503-846-5800. Dick Schouten, District 1 Desari Strader, District 2 Roy Rogers, District 3 Attention: Andy Duyck, District 4 Washington County Elections prints information as submitted. We do not correct spelling, punctuation, grammar, syntax, errors or inaccurate information. W-2 W-3 W-4 WASHINGTON COUNTY Commissioner, District 3 Roy R. Rogers (Nonpartisan) OCCUPATION: Certified Public Accountant /County Commissioner OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: Managing Partner of large local firm. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Portland State University; Bachelor of Science Degree; Numerous additional courses in finance, management, and public finance. PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: County Commissioner (current); Mayor, City of Tualatin (3 terms); President Oregon Mayors Association; Clean Water Services Board; Numerous State, Regional and County Transportation and Planning Committees; Board Member of Enhanced Sheriffs Patrol, Urban Road Maintenance and Housing Authority Districts ROY IS INVOLVED! • Tigard First Citizen • Past President - Tigard Rotary, Tigard Chamber, Tigard -

Ellen Rosenblum Sworn in As Attorney General 1989 -2012 T the Oregon State Capitol, Ellen Rosenblum Was Sworn in As Attorney General of Oregon on June 29

Published Quarterly by Oregon Women Lawyers Volume 23, No. 3 Summer 2012 23 years of breaking barriers Ellen Rosenblum Sworn In as Attorney General 1989 -2012 t the Oregon State Capitol, Ellen Rosenblum was sworn in as attorney general of Oregon on June 29. AGovernor John Kitzhaber had appointed her to the office, vacated by John Kroger. She is the first woman to President serve as Oregon’s attorney general. Megan Livermore Governor Kitzhaber welcomed the overflowing crowd Vice President, President-Elect of Ellen’s friends, colleagues, and family, and the press, Kathleen J. Rastetter and introduced Oregon’s first female governor, Barbara Secretary Kendra Matthews Roberts. Following Governor Roberts was Justice Virginia Linder, the first woman to win a seat on the Oregon Su- Treasurer Laura Craska Cooper preme Court through a contested election. Both women Historian observed the historic nature of this appointment. Elizabeth Tedesco Milesnick After being sworn in by Governor Kitzhaber, Ellen said that she would lead the Department of Justice “so that Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum (left) Board Members and Justice Virginia Linder on June 29 Allison Boomer Oregon’s interests are represented at the highest level of Hon. Frances Burge ethics, professionalism, and devotion to public service.” Megan Burgess Gina Eiben Following the swearing-in ceremony was a public reception at the Mission Mill Dye House in Dana Forman Salem, where hundreds gathered to congratulate our new attorney general. Heather L. Weigler, Amber Hollister OWLS’ past president and Ellen’s campaign manager during the primary campaign, introduced her. Jaclyn Jenkins Angela Franco Lucero “Ellen isn’t motivated by what’s right for her; she’s motivated by what’s right for all of us. -

2009 Annual Report

D i s c o v e r C o n n e c t C h a n g e DUTCHESS COMMUNITY COLLEGE NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE FOUNDATION PAID 53 Pendell Road NEWBURGH, NY Poughkeepsie, New York 12601-1595 PERMIT NO. 44 DUTCHESS COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOUNDATION 2009 D U T C H E S S C O M M U N I T Y C O L L E G E A N N U A L R E P O R T ‘Man's mind, once stretched by a new idea, never regains its D i s c o v e r C o n n e c t C h a n g e original dimensions.’ ~ Oliver Wendell Holmes Dear Friends and Alumni ever before in Dutchess Community Colleges history have our faculty, staff and Nservices touched the lives of so many students. Record-breaking enrollment of 9,794 students for the Fall 2009 semester (with continued momentum this Spring) is a testament to the quality and value DCC provides, especially during financially challenging times. Our college community pulled together to serve this unprecedented influx of students by stepping up our advising and registration capabilities and adding faculty and courses. Some other community colleges werent as proactive in meeting the challenge, closing admission to fall credit classes or turning away new students. Fortunately, we were able and will continue to be here for our students and community. However, because of the difficult economic situation our students are facing, we need your assistance now more than ever. -

I-5 Scar of Displacement Revisited

Black History Month PO QR code ‘City of www.portlandobserver.com Volume XLVV • Number 4 Roses’ Wednesday • February 24, 2021 Committed to Cultural Diversity I-5 Scar of Displacement Revisited ODOT takes another look at Rose Quarter project BY BEVERLY CORBELL A swath Portland centered at Broadway and Weidler is cleared for construction of the I-5 freeway in this 1962 THE PORTLAND OBSERVER photo from the Eliot Neighborhood Association. Even many of the homes still standing were later lost to In June of last year, the nonprofit Albina Vision Trust demolition as the historic African American neighborhood was decimated over the 1960s and early 1970s, not sent an email to the Oregon Department of Transportation only for I-5, but to make room for the Memorial Coliseum, its parking lots, the Portland Public School’s Blanchard withdrawing support for its proposed I-5 Rose Quarter Im- Building, I-405 ramps, and Emanuel Hospital’s expansion. provement Project, which would reconfigure a 1.8-mile stretch of I-5 between the Interstate 84 and Interstate 405 the grassroots effort that began in 2017 to remake the Rose interchanges. Quarter district into a fully functioning neighborhood, em- According to Winta Yohannes, Albina Vision’s manag- bracing its diverse past and re-creating a landscape that can ing director, the proposal didn’t go far enough to mitigate accommodate much more than its two sports and entertain- the harm done to the Black community in the Albina neigh- ment venues, but with several officials, including Mayor borhood when hundreds, maybe thousands, of homes and Ted Wheeler, also dropping support for the project. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

Rose Quarter: I-5/Broadway-Weidler Project Environmental Justice-Oriented Interviews Summary of Findings

Rose Quarter: I-5/Broadway-Weidler Project Environmental Justice Interviews Summary and Findings from Interviews with 17 African American community members Portland, Oregon February 16, 2017 Rose Quarter: I-5/Broadway-Weidler Project Environmental Justice-Oriented Interviews Summary of Findings Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 FAQs and Background ................................................................................................................................... 5 History of Area, Drivers for Changes, Shifts in Demographics & Contributing Factors ................................ 6 Vanport and the Shipyards .............................................................................................................. 6 Legacy Emanuel Hospital ................................................................................................................. 7 Rose Quarter/Moda Center ............................................................................................................. 7 Interstate 5 (I-5) ............................................................................................................................... 8 Coliseum........................................................................................................................................... 8 Redlining and Real Estate................................................................................................................ -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

Records Officer

Metro Councilor Caroline Miller District 8, 1979 to 1980 Oral History Caroline Miller Metro Councilor, District 8 1979 – 1980 Caroline Miller grew up in Santa Monica, California, to a Costa Rican mother and American father. Eventually she made her way to Oregon where she enrolled as a student at Reed College and received her Bachelor of Arts and later, her Masters of Arts in Teaching. She also received a second Masters of Arts degree in Literature from the University of Arizona, Flagstaff. After graduating, Ms. Miller adventured to England, Europe and Africa, eventually teaching in England and Rhodesia. (Zimbabwe). Upon her return to Oregon, after working as a teacher at Wilson High School (Portland), she applied her talents and education to political pursuits, heading the Portland Federation of Teachers #111 and lobbying for education in 1977. Ms. Miller’s credentials in the political arena grew as she assumed the role of the first woman Parliamentarian for the Oregon AFL/CIO Conventions; campaigned actively for Neil Goldschmidt (mayoral campaign); served on the City of Portland Economic Advisory Committee; and won a seat on the Metropolitan Service District (MSD) Council in 1979 (representing District 8). Caroline Miller’s journey through the public spectrum continued when she became a Multnomah County commissioner in 1980. After leaving political office in 1988, Ms. Miller became a volunteer mediator for the Multnomah County court system – a position that she held for over seventeen years. She also pursued a writing career and became a published author of short fiction stories. In addition, Ms. Miller’s artistic interests have resulted in installations of her silk paintings in galleries around Portland. -

“We'll All Start Even”

Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives Gary Halvorson, Oregon State “We’ll All Start Even” White Egalitarianism and the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act KENNETH R. COLEMAN THIS MURAL, located in the northwest corner of the Oregon State Capitol rotunda, depicts John In Oregon, as in other parts of the world, theories of White superiority did not McLoughlin (center) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) welcoming Presbyterian missionaries guarantee that Whites would reign at the top of a racially satisfied world order. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding to Fort Vancouver in 1836. Early Oregon land bills were That objective could only be achieved when those theories were married to a partly intended to reduce the HBC’s influence in the region. machinery of implementation. In America during the nineteenth century, the key to that eventuality was a social-political system that tied economic and political power to land ownership. Both the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the 1857 Oregon Constitution provision barring Blacks from owning real Racist structures became ingrained in the resettlement of Oregon, estate guaranteed that Whites would enjoy a government-granted advantage culminating in the U.S. Congress’s passing of the DCLA.2 Oregon’s settler over non-Whites in the pursuit of wealth, power, and privilege in the pioneer colonists repeatedly invoked a Jacksonian vision of egalitarianism rooted in generation and each generation that followed. White supremacy to justify their actions, including entering a region where Euro-Americans were the minority and — without U.S. sanction — creating a government that reserved citizenship for White males.3 They used that govern- IN 1843, many of the Anglo-American farm families who immigrated to ment not only to validate and protect their own land claims, but also to ban the Oregon Country were animated by hopes of generous federal land the immigration of anyone of African ancestry. -

2016 Portland Hotel Guide

Portland Hotel Guide HouseSpecial 2016 housespecial.com Airport 12 420 NE 9th Ave. 10 2 11 8 7 4 3 6 1 5 9 North WELCOME TO PORTLAND Here are some hotel suggestions for your stay. Hopefully, this will give you a little taste of the city and make your decision a bit easier. We know you’re going to love Portland — we sure do. 1 The Nines HOUSESPECIAL RATE HOTELS 2 Ace Hotel The Nines .....................................................................page 3 3 Hotel Lucia Ace Hotel .....................................................................page 4 4 Hotel deLuxe Hotel Lucia ...................................................................page 5 Hotel deLuxe ................................................................page 6 5 Hotel Monaco Hotel Monaco...............................................................page 7 Sentinel Hotel ..............................................................page 8 6 Sentinel Hotel Hotel Vintage ...............................................................page 9 7 Hotel Vintage Hotel Eastlund..............................................................page 10 8 Benson Hotel 9 The Heathman Hotel STANDARD RATE HOTELS Benson Hotel ...............................................................page 11 10 Jupiter Hotel The Heathman .............................................................page 12 11 The Westin Jupiter Hotel ................................................................page 13 The Westin ...................................................................page 14 12 Hotel