Swiss Private Banking Microeconomics of Competitiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

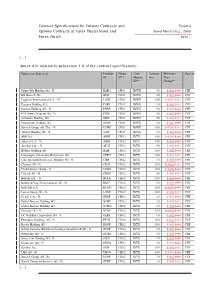

Contract Specifications for Futures Contracts and Eurex14 Options Contracts at Eurex Deutschland and Stand March 2831, 2008 Eurex Zürich Seite 1

Contract Specifications for Futures Contracts and Eurex14 Options Contracts at Eurex Deutschland and Stand March 2831, 2008 Eurex Zürich Seite 1 [....] Annex A in relation to subsection 1.6 of the contract specifications: Futures on Shares of Produkt- Group Cash Contract Minimum Currency ID ID** Market- Size Price ID** Change* Julius Bär Holding AG - N. BAEG CH01 XSWX 50 0.0010.01 CHF BB Biotech AG BIOF CH01 XSWX 50 0.0010.01 CHF Logitech International S.A. - N. LOGF CH01 XSWX 100 0.00010.01 CHF Pargesa Holding S.A. PARF CH01 XSWX 10 0.0010.01 CHF Sonova Holding AG - N. PHBF CH01 XSWX 50 0.0010.01 CHF PSP Swiss Property AG - N. PSPF CH01 XSWX 50 0.0010.01 CHF Schindler Holding AG SINF CH01 XSWX 50 0.0010.01 CHF Straumann Holding AG STMF CH01 XSWX 10 0.0010.01 CHF Swatch Group AG, The - N. UHRF CH01 XSWX 100 0.00010.01 CHF Valiant Holding AG - N. VATF CH01 XSWX 10 0.0010.01 CHF ABB Ltd. ABBF CH02 XVTX 100 0.00010.01 CHF Adecco S.A. - N. ADEF CH02 XVTX 100 0.0010.01 CHF Actelion Ltd. - N. ATLG CH02 XVTX 50 0.0010.01 CHF Bâloise Holding AG BALF CH02 XVTX 100 0.0010.01 CHF Compagnie Financière Richemont AG CFRH CH02 XVTX 100 0.0010.01 CHF Ciba Spezialitätenchemie Holding AG - N. CIBF CH02 XVTX 10 0.0010.01 CHF Clariant AG - N. CLNF CH02 XVTX 100 0.00010.01 CHF Credit Suisse Group - N. CSGG CH02 XVTX 100 0.00010.01 CHF Geberit AG - N. -

Strategy of Swiss Banking Sector Towards Digitalization Trends

UDC: 336.7/005.91:005.21]:004(494) STRATEGY OF SWISS BANKING SECTOR TOWARDS DIGITALIZATION TRENDS Sead Jatic1, Milena Ilic2, Lidija Miletic3, Aca Markovic4 1Finance-Doc Multimanagement AG, Zürich, Switzerland 2Information Technology School - ITS, Belgrade, Serbia 3Information Technology School - ITS, Belgrade, Serbia 4Faculty of business studies and law, University “Union - Nikola Tesla”, Belgrade, Serbia, [email protected] Abstract: Many fields of management in contemporary banking organizations have flourished due to advancement in engineering and technology particularly, in the IT sector. Innovations which lead to digitalization assisted banks in improving business processes, ensuring competitive advantage, achiev- ing better business results and, finally, gaining higher profits. The process of digitalization in banking requires a simple approach in order to make use of banking services by means of modern technologies easier, faster and cheaper. Digitalization in banking forced modern banks to reassess and change their traditional business methods that are for the most part based on the existence of “bricks-and-mortar” physical locations and to replace them with modern distribution channels, namely modern media, and the banking services based on them. Keywords: banks, banking sector, business models, digitalization, innovation 1. INTRODUCTION Digitalization is a process which shall engage all banks in the global market in the future, and banks that had recognized the importance of this process have already begun prospering in the market. The process of digitalization refers to an organized, concise ap- proach in which the services are provided in a far more simple and rapid way due to the im- plementation of modern technology. The purpose of research paper to analyze the influence that digitalization has on contemporary banks’ management and to establish the perspec- tive of this process in the future. -

31 December 2017 Reporting Date

M Reporting date: 31 December 2017 Reporting date: 31 December 2017 1 Content Group structure and ownership 3 Board of Directors 3 Executive Board 6 Basis and components of compensation for the members of the Board of Directors and the Executive Board 7 Components of the remuneration 7 Risk management framework and process 8 Auditing body 10 Cover image: Detail of the inlaid parquet floor in the South passage adjacent to the Ballroom on the second floor piano nobile of the Liechtenstein City Palace, executed by Michael Thonet © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna 2 Corporate Governance The binding principles of corporate governance are set out in the company’s articles of incorporation, the organizational and governance regulations, as well as in the regulations of the Board of Directors Committees and are defined in detail in corresponding directives. As a bank domiciled in Switzerland, we are subject to supervision by FINMA and are therefore required to implement all applicable regulations. The following information on corporate governance is in accordance with FINMA Circular 2016/1 (Annex 4). Group structure and ownership LGT Bank (Switzerland) Ltd. is ultimately owned by LGT Group Holding Ltd. LGT Group Holding Ltd. is 100 percent controlled by LGT Group Foundation. LGT Group Foundation is 100 percent controlled by the Prince of Liechtenstein Foundation (POLF), the beneficiary of which is H.S.H. Reigning Prince Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein. The participations of LGT Bank (Switzerland) Ltd. are not relevant to the overall assessment of the company, and no consolidated financial statements are therefore prepared. -

Richemont & Its Maisons

PUBLIC at a glance PUBLIC CONTENTS 3 THE GROUP AT A GLANCE 8 HOW WE OPERATE 12 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 18 OUR LATEST FIGURES 23 APPENDIX PUBLIC * THE GROUP AT A GLANCE *End March 2020 **Dec 2020 Founded A leading luxury in 1988 goods group CHF 42 bn** € 14 bn € 1.5 bn € 2.4 bn Market capitalisation Sales Operating profit Net cash Top 8 SMI Top 3 JSE 3 PUBLIC THE GROUP AT A GLANCE * *End September 2020 25 Maisons and businesses Over 35 000 Employees (including over 8 000 in Switzerland) 7 Schools 9 Main Foundations 2 186 Boutiques supported (of which 1 179 internal) Richemont Headquarters by architect Jean Nouvel, Geneva 4 PUBLIC FROM THE PAST INTO THE FUTURE 206 187 173 152 127 114 101 68 25 18 1755 1814 1830 1833 1845 1847 1860 1868 1874 1893 1906 1919 1928 1952 1983 1995 2001 2002 2015 2021 * 265 190 175 160 146 114 92 37 19 5 *Both YOOX and NET-A-PORTER were founded in 2000 5 PUBLIC 1988 – 2020: UNIQUE PORTFOLIO MOSTLY BUILT BY ACQUISITIONS 1988 1990’s 2000’s 2010’s 2020’s 6 10 15 24 25 6 PUBLIC A WORLDWIDE PRESENCE * *End March 2020 Sales by geographical area Japan Middle East and Africa 8% 7% Americas 20% Europe Operating in 30% Europe 36 Europe locations Asia Pacific 35% 2 166 boutiques Cartier store in Cannes, France 7 PUBLIC HOW WE OPERATE PUBLIC WHAT WE STAND FOR Our Corporate culture is determined by the Collegiality Freedom principles we live by They affect what we do and why we do it They shape how we behave every day — in all areas Solidarity Loyalty of our business 9 PUBLIC HOW OUR BUSINESS OPERATES We work as business partners Headquarters Our Maisons and businesses SEC Strategy, Capital Allocation are directly in charge of: Strategic Product & Guide the Maisons by verifying that decisions on Products, Communication Committee Communication and Distribution are appropriate and consistent with . -

Sales Prospectus with Integrated Fund Contract Clariden Leu (CH) Swiss Small Cap Equity Fund

Sales Prospectus with integrated Fund Contract Clariden Leu (CH) Swiss Small Cap Equity Fund September 2011 Contractual fund under Swiss law (type "Other funds for traditional investments") Clariden Leu (CH) Swiss Small Cap Equity Fund was established by Swiss Investment Company SIC Ltd., Zurich, as the Fund Management Company and Clariden Leu Ltd., Zurich, as the custodian bank. This is an English translation of the offical German prospectus. In case of discrepancies between the German and English text, the German text shall prevail. Part I Prospectus This Prospectus with integrated Fund Contract, the Simplified Prospectus and the most recent annual or semi-annual report (if published after the latest annual report) serve as the basis for all subscriptions of Shares in this Fund. Only the information contained in the Prospectus, the Simplified Prospectus or in the Fund Contract will be deemed to be valid. 1 General information Main parties Fund Management Company: Swiss Investment Company SIC Ltd. Claridenstrasse 19, CH-8002 Zurich Postal address: XS, CH-8070 Zurich Phone: +41 (0) 58 205 37 60 Fax: +41 (0) 58 205 37 67 Custodian Bank, Paying Agent and Distributor: Clariden Leu Ltd. Bahnhofstrasse 32, CH-8070 Zurich Phone: +41 (0) 844 844 001 Fax: +41 (0) 58 205 62 56 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.claridenleu.com Investment Manager: Clariden Leu Ltd. Bahnhofstrasse 32, CH-8070 Zurich Phone: +41 (0) 844 844 001 Fax: +41 (0) 58 205 62 56 Auditors: KPMG Ltd Badenerstrasse 172, CH-8004 Zurich 2 Information on the Fund 2.1 General information on the Fund Clariden Leu (CH) Swiss Small Cap Equity Fund is an investment fund under Swiss law of the type “Other funds for traditional investments” pursuant to the Swiss Federal Act on Collective Investment Schemes of June 23, 2006. -

Press Release

Press release Zurich/Geneva, 17 April 2019 Global Powers of Luxury Goods: Swiss luxury companies are taking the digital path to accelerate growth • The sales of the world’s Top 100 luxury goods companies grew by 11% and generated aggregated revenues of USD 247 billion in fiscal year 2017 • Richemont, Swatch Group and Rolex remain in the top league of Deloitte’s Global Powers of Luxury Goods ranking • All Swiss companies in the Top 100 returned to growth in FY2017, but with only 8% increase, they lagged behind the whole market for the third time in a row • Luxury goods companies are making significant investments in digital marketing and the use of social media to engage their customers Despite the recent slowdown of economic growth in major markets including China, the Eurozone and the US, the luxury goods market looks positive. In FY2017, the world’s Top 100 luxury goods companies generated aggregated revenues of USD 247 billion, representing composite sales growth of 10.8%, according to Deloitte’s 2019 edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. For comparison, in FY2016 sales were USD 217 billion and annual sales growth was as low as 1.0%. Three-fourth of the companies (76%) reported growth in their luxury sales in FY2017, with nearly half of these recording double-digit year-on-year growth. Switzerland and Hong Kong prevail in the luxury watches sector Looking at product sectors, clothing and footwear dominated again in FY2017, with a total of 38 companies. The multiple luxury goods sector represented the largest sales share (30.8%), narrowly followed by jewellery and watches (29.6%). -

Investing Sustainably Bauer Brothers, Hortus Botanicus, Detail from “Cucurbita Pepo L.,” Ca

VALUES WORTH SHARING Investing sustainably A look inside the Princely Collections: The illustrations in this publication are part of the Codex Liechtenstein – in the Codex’s more than 2700 separate plant illustrations, it was primarily the three Bauer brothers who created a synthesis of art and science: faithful in detail, yet obeying the high aesthetic requirements of art. For more than 400 years, the Princes of Liechtenstein have to accompany what we do. For us, they embody those been passionate art collectors. The Princely Collections values that form the basis for a successful partnership include key works of European art stretching over five with our clients: a long-term focus, skill and reliability. centuries and are now among the world’s major private art collections. The notion of promoting fine arts for the Cover image: Bauer brothers, Hortus Botanicus, general good enjoyed its greatest popularity during the detail from “Tropaeolum majus,” 1779 Baroque period. The House of Liechtenstein has pursued © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna this ideal consistently down the generations. We make deliberate use of the works of art in the Princely Collections www.liechtensteincollections.at Bauer brothers, Hortus Botanicus, detail from “Cucurbita ca. pepo 1778 L.,” Contents 5 Investors can change the world 6 Why we must take action 8 What can investors do? 10 Who benefits from sustainable investments? 14 Investing sustainably with LGT 18 Impact investing for better healthcare 19 Venture philanthropy in the fight against HIV transmission “Asset management in particular gives us the opportunity to make an important contribution to resolving environmental and social issues through the sustainable allocation of capital.” H.S.H. -

Switzerland in the Second World War

To Our American Friends: Switzerland in the Second World War By Dr. Hans J. Halbheer, CBE Honorary Secretary of the American Swiss Foundation Advisory Council in Switzerland and a Visiting Scholar at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, California Dr. Halbheer wrote the following essay in 1999 to offer a Swiss perspective on some issues of the recent controversy to American friends of Switzerland. In addressing the arguments raised by U.S. critics of the role of Switzerland during the Second World War, I am motivated both by my feelings of friendship towards America and by my Swiss patriotism. For both of these reasons, I feel deeply hurt by both the charges against my country and the vehemence with which they have been expressed. During a recent period of residency at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, one of the leading U.S. think tanks, I sought to present my personal standpoint regarding the lack of understanding about Switzerland’s role during the Second World War in many discussions with Americans both young and old. On these occasions, I emphasized my awareness of the fact that the criticisms of Switzerland came only from a small number of Americans. Despite the settlement reached in August 1998 between the two major Swiss banks (Credit Suisse Group and UBS) and two Jewish organizations (the World Jewish Congress and the World Jewish Restitution Organization), the matter has still not run its course, although it has widely disappeared from the American media. Unfortunately, I must maintain that as a result of the generally negative portrayal of Switzerland over the past few years, the image of Switzerland has suffered. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, the Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), Ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, E

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), ix. 2. Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon, 1799–1815 (London, 1996), 3. 3. An exception to the Franco-centric bibliography in English prior to the last decade is Owen Connelly, Napoleon’s Satellite Kingdoms (New York, 1965). Connelly discusses the developments in five satellite kingdoms: Italy, Naples, Holland, Westphalia, and Spain. Two other important works that appeared before 1990, which explore the internal developments in two countries during the Napoleonic period, are Gabriel Lovett, Napoleon and the Birth of Modern Spain (New York, 1965) and Simon Schama, Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780–1813 (London, 1977). 4. Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe (London and New York, 1991), 8–13. 5. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 102–5; Broers, Europe under Napoleon, passim. 1 THE FORMATION OF THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE 1. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 105. 2. Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (New York, 1994), 43. 3. Ellis, “The Nature,” 104–5. 4. On the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and international relations, see Tim Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787–1802 (London, 1996); David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon: the Mind and Method of History’s Greatest Soldier (London, 1966); Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military 212 Notes 213 Campaigns (Wilmington, DE, 1987); J. -

Swiss Banking Business Models of the Future Download the Report

Swiss Banking Business Models of the future Embarking to New Horizons Deloitte Point of View Audit. Tax. Consulting. Financial Advisory. Contents Management summary 2 Overview of the report 5 Chapter 1 – Key trends impacting banking 6 Chapter 2 – Disruptive innovations reshaping banking 17 Chapter 3 – Likely scenarios for banking tomorrow 26 Chapter 4 – Future business model choices 31 Chapter 5 – Actions to be taken 39 Contact details 43 The banking market in Switzerland is undergoing significant change and all current business models are under scrutiny. Among several universal trends and Switzerland-specific market factors affecting banks and their customers, ‘digitisation’ is the most significant. In addition upcoming new regulations will drive more changes to business models than any regulations in Switzerland have ever done before. Deloitte has produced this report, based on extensive research and fact-finding, to assess how major trends and disruptive innovations will re-shape the business of banking in the future. The report addresses the following questions: • What are the key trends affecting banks and their customers? • What are the main innovations that are being driven by these key trends? • Which scenarios can be predicted for the banking industry of tomorrow? • What will be the most common business models for banks in the future? • How should banks make their strategic choice? This report will not give you definite answers, but it should indicate how to start addressing the question: “Where do we want to position ourselves in the banking market of the future?” Yours sincerely, Dr. Daniel Kobler, Partner Jürg Frick, Senior Partner Adam Stanford, Partner Lead Author, Banking Innovation Leader Banking Industry Leader Consulting Leader Financial Services Swiss Banking Business Models of the future Embarking to New Horizons 1 Management summary (1/3) Digitisation as a main Banks need to adapt their business models to key trends and disruptive innovations that are driver of change already having an impact on society and the economy. -

LGT Capital Management Ltd

LGT Capital Management Ltd. European SRI Transparency Code European SRI Transparency Code Disclaimer This document aims at fulfilling reporting requirements under the European SRI Transparency Guidelines. It does not constitute a public offering or public advertisement of any financial instruments mentioned herein. This document is not directed at recipients in any jurisdictions where the receipt of the information contained herein would be unlawful. The receipt of this information is not to be taken as constituting the giving of investment advice. Each person should make its own independent assessment and should take its own professional advise in relation to any investment product mentioned herein. Please be advised that investors should always consult the legal documentation of the investment products mentioned herein. The information contained in this document was obtained from a number of different sources. LGT exercises the greatest care when choosing the sources of information and compiling obtained information. Nevertheless errors or omissions in information obtained from different sources cannot be excluded. LGT does not assume any liability for any direct or indirect damage or loss resulting from the use of this document. This document and the information contained herein may be reproduced only with the prior written consent of LGT. To the extent that past performance of investment products is mentioned in this document please note that past performance is not an appropriate indicator for future performance. 2 / 25 European SRI Transparency Code European SRI Transparency Code Version 3.0 The European SRI Transparency Code (the Code) focuses on SRI funds distributed publicly in Europe and has been designed to cover a range of assets classes, such as equity and fixed income. -

Benchmarking Mobile Banking in Switzerland Today

BENCHMARKING MOBILE BANKING IN SWITZERLAND TODAY CAPCO DIGITAL SWITZERLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 01 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................................................................. 02 Mobile Banking Is Reaching a New Threshold ................................................................................................................................. 03 Is Omnichannel Dead? .................................................................................................................................................................. 05 It’s Not Just Apps – It’s the Products and Pricing ............................................................................................................................. 06 Capco 2020 Mobile Banking Benchmark ........................................................................................................................................ 08 Digital Pricing Strategy .................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Concluding Thoughts ....................................................................................................................................................................