Dance with Us: Virginia Tanner, Mormonism, and Humphrey's Utah Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

Star Dance Workshop Series

Jo’s Footwork and The Dance Workshop present “ Star Dance Workshop Series” 2018/2019 S The classes will be held at S T ►Jo’s Footwork Studio (708) 246-6878 – 1500 Walker Street, Western Springs – Studio I OR T ► A The Dance Workshop, (708) 226-5658 - 9015 West 151st Street, Orland Park – Studio I. A R S T A R D A N C E W O R S K H O P S E R I E S R ►Sunday, November 11, 2018 ~ T A P -with Star Dixon Location: The Dance Workshop (DWS) Continuing thru Intermediate 1:00pm – 2:30pm Intermediate/Advanced 2:30pm – 4:00pm D Star Dixon ~ is an assistant director, choreographer, and original principal dancer of world renowned tap company, MADD Rhythms . She has taught and D performed at the most distinguished tap festivals in the country including The L.A. Tap Fest, DC Tap Fest, Motorcity Tap Fest, Chicago Human Rhythm A A Project's Rhythm World, Jazz City in New Orleans, and MADD Rhythms own Chicago Tap Summit . Internationally, she's taught and performed in Poland, N Japan, and Brazil several times. She's been featured in Dance Spirit Magazine twice (Artist on the rise & Speed Demon), The Chicago Reader, & independent N film "The Rise & Fall of Miss Thang" starring Dormeshia Sumbry Edwards. Outside of MADD Rhythms, she's performed as a guest with such companies as C Michelle Dorrance's Dorrance Dance, Chloe Arnold's Syncopated Ladies, Lane Alexander's Bam, and Jason Samuel Smith's ACGI. Star is currently on staff at C E numerous dance studios, schools, and After School Matters. -

Harriet Berg Dance Collection

Harriet Berg Dance Collection Papers, 1948-2002 (Predominately 1960-1980) 30 linear feet Accession #1608 Provenance The Harriet Berg Dance Collection was first given to Wayne State University in 1984 by Harriet Berg, and has been added to over the years since that time (up to 2002). Bio/Historical Info For over 40 years Mrs. Berg has been a choreographer, teacher, performer, and arts avocate. She received her B.A. in Art Education and her M.A. in Humanities from Wayne State University. She has taught at Wayne State, the Jewish Community Center (and Camp Tamarack), Burton School, and Bloomfield Hills Academy locally and the Connecticut College Summer School of Dance and the Perry-Mansfield Dance-Drama School nationally. She was the director of the Festival Dancers and Young Dancers Guild at the Jewish Community Center and directed the Renaissance Dance Company and the Madame Cadillac Dancers, both companies specializing in historical dance. In addition to her professional work Mrs. Berg has served as member and Dance committee chairman for the Michigan Council of the Arts, the Detroit Council for the Arts, the Detroit Adventure Planning Project, Michigan Foundation for the Arts and the Detroit Metropolitan Dance Project. Mrs. Berg’s collection reflect her interest in all aspects of dance, and other performing and fine arts. Some of the papers also reflect some aspects of her personal life as well as that of her family members. Subjects American Dance Festival Harriet Berg Choreographers Choreography Connecticut College Dance Books Dance Companies Dance Education Dance in Detroit Detroit Metropolitan Dance Project Historical Dance Isadora Duncan Jewish Community Center Madame Cadillac Dance Theater Michigan Dance Association Modern Dance Renaissance Dance Company Resources for Dance Wayne State University Correspondents Kay Bardsley Harriet Berg Irving Berg Leslie Berg Martin Berg Merce Cunningham Raymond Duncan Louis Falco Martha Graham Lucas Hoving Jose Limon Paul Taylor J.J. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

Keigwin + Company

presents KEIGWIN + COMPANY LARRY KEIGWIN Artistic Director ANDREA LODICO WELSHONS Executive Director NICOLE WOLCOTT Co-Founder/Education Director BRANDON COURNAY Rehearsal Director & Company Manager RANDI RIVERA Production & Stage Manager DANCERS ZACKERY BETTY, KACIE BOBLITT, BRANDON COURNAY, KILE HOTCHKISS, GINA IANNI, EMILY SCHOEN, JACLYN WALSH, NICOLE WOLCOTT 1 KEIGWIN + COMPANY EPISODES (2014) LOVE SONGS (2006) CHOREOGRAPHY Larry Keigwin CHOREOGRAPHY Larry Keigwin with the Company LIGHTING DESIGN Burke Wilmore LIGHTING DESIGN Burke Wilmore COSTUMES Sarah Laux COSTUMES Fritz Masten MUSIC On the Town – Three Dance Episodes, Leonard Bernstein MUSIC Roy Orbison “Blue Bayou” and “Crying” DANCERS Zackery Betty, Kacie Boblitt / Gina DANCERS Emily Schoen & Brandon Cournay Ianni*, Brandon Cournay, Kile Hotchkiss, Emily UNDERSTUDY Gina Ianni Schoen, Jaclyn Walsh MUSIC Aretha Franklin “Baby, I Love You” and “I Episodes was commissioned by the John F. Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and DANCERS Jaclyn Walsh & Zackery Betty the National Symphony Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach, Music Director, as part of the 2014 MUSIC Nina Simone “Ne Me Quitte Pas” NEW Moves: Symphony + Dance. and “I Put a Spell on You” *alternating cast DANCERS Nicole Wolcott & Larry Keigwin Love Songs was created in part with generous CONTACT SPORT (2012) support from The Greenwall Foundation. CHOREOGRAPHY Larry Keigwin MUSIC “Monotonous,” Lyrics by June Carroll & TRIPTYCH (2009) Music by Arthur Siegel; Performed by Eartha CHOREOGRAPHY -

State High School Dance Festival 2014 – BYU Adjudicator and Master Class Teacher Bios

Utah Dance Education Organization State High School Dance Festival 2014 – BYU Adjudicator and Master Class Teacher Bios Kay Andersen received his Master of Arts degree at New York University. He resided in NYC for 15 years. From 1985-1997 he was a soloist with the Nikolais Dance Theatre and the Murray Louis Dance Company. He performed worldwide, participated in the creation of important roles, taught at the Nikolais/Louis Dance Lab in NYC and presented workshops throughout the world. At Southern Utah University he choreographs, teaches improvisation, composition, modern dance technique, tap dance technique, is the advisor of the Orchesis Modern Dance Club, and serves as Chair of the Department of Theatre Arts and Dance. He has choreographed for the Utah Shakespearean Festival and recently taught and choreographed in China, the Netherlands, Mexico, North Carolina School of the Arts, and others. Kay Andersen (SUU) Ashley Anderson is a choreographer based in Salt Lake City. Her recent work has been presented locally at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, the Rio Gallery, the BYU Museum of Art, Finch Lane Gallery, the City Library, the Utah Heritage Foundation’s Ladies’ Literary Club, the Masonic Temple and Urban Lounge as well as national venues including DraftWork at Danspace Project, BodyBlend at Dixon Place, Performance Mix at Joyce SOHO (NY); Mascher Space Cooperative, Crane Arts Gallery, the Arts Bank (PA); and the Taubman Museum of Art (VA), among others. Her work was also presented by the HU/ADF MFA program at the American Dance Festival (NC) and the Kitchen (NY). She has recently performed in dances by Ishmael Houston-Jones, Regina Rocke & Dawn Springer. -

Zvidance DABKE

presents ZviDance Sunday, July 12-Tuesday, July 14 at 8:00pm Reynolds Industries Theater Performance: 50 minutes, no intermission DABKE (2012) Choreography: Zvi Gotheiner in collaboration with the dancers Original Score by: Scott Killian with Dabke music by Ali El Deek Lighting Design: Mark London Costume Design: Reid Bartelme Assistant Costume Design: Guy Dempster Dancers: Chelsea Ainsworth, Todd Allen, Alex Biegelson, Kuan Hui Chew, Tyner Dumortier, Samantha Harvey, Ying-Ying Shiau, Robert M. Valdez, Jr. Company Manager: Jacob Goodhart Executive Director: Nikki Chalas A few words from Zvi about the creation of DABKE: The idea of creating a contemporary dance piece based on a Middle Eastern folk dance revealed itself in a Lebanese restaurant in Stockholm, Sweden. My Israeli partner and a Lebanese waiter became friendly and were soon dancing the Dabke between tables. While patrons cheered, I remained still, transfixed, all the while envisioning this as material for a new piece. Dabke (translated from Arabic as "stomping of the feet") is a traditional folk dance and is now the national dance of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and Palestine. Israelis have their own version. It is a line dance often performed at weddings, holidays, and community celebrations. The dance strongly references solidarity, and traditionally only men participated. The dancers, linked by hands or shoulders, stomp the ground with complex rhythms, emphasizing their connection to the land. While the group keeps rhythm, the leader, called Raas (meaning "head"), improvises on pre-choreographed movement phrases. He also twirls a handkerchief or string of beads known as a Masbha. When I was a child and teenager growing up in a Kibbutz in northern Israel, Friday nights were folk dance nights. -

Dance Magazine

11/11/2020 This Choreographer Directs a Physically Integrated Flamenco Company in Spain - Dance Magazine José Galán (bottom) with Lola López. Photo by Ginette Lavell, Courtesy Galán This Choreographer Directs a Physically Integrated Flamenco Company in Spain Bridgit Lujan Nov 04, 2020 Spain's José Galán challenges audiences to rethink how they perceive those who are disabled. For the past decade, he has directed Compañía José Galán de Flamenco Inclusivo, a professional company that features artists in wheelchairs, with vision impairment and with Down syndrome alongside dancers without disabilities. Regarded as the foremost expert of flamenco dance for people with disabilities, his trailblazing productions require a mindful gaze on the dancers' bodies. Along with his company, his instructional method, Inclusive Flamenco, has been presented across the globe at flamenco's top dance festivals and events. He recently spoke with Dance Magazine about how he got into this work and how he collaborates with his dancers. https://www.dancemagazine.com/disability-flamenco-2648443561.html?rebelltitem=4#rebelltitem4 1/8 11/11/2020 This Choreographer Directs a Physically Integrated Flamenco Company in Spain - Dance Magazine José Galán (left) with Lola López Ginette Lavell, Courtesy Galán How he started his company: "I improvised for the first time with a group of people with Down syndrome as an undergraduate pedagogy student. I fell in love with their ways of feeling, expressing and the trusting relationship they formed with me without even knowing me. It awakened my interest in approaching dance from another place. "In Madrid I danced with Ballet Flamenco Sara Baras and also an inclusive theater and contemporary dance company, El Tinglao. -

"Who's Right? Whose Rite? American, German Or Israeli Views of Dance" by Judith Brin Ingber

Title in Hebrew: "Nikuudot mabat amerikiyot, germaniyot ve-yisraliot al ma<h>ol: masa aishi be'ekvot ha-hetpat<h>ot ha-ma<h>olha-moderni ve-haammami be-yisrael" m --- eds. Henia Rottenbergand Dina Roginsky, Dance Discourse in Israel, published by Resling, Tel Aviv, Israel in200J "Who's Right? Whose Rite? American, German or Israeli Views of Dance" By Judith Brin Ingber The crux of dance writing, history, criticism, research, teaching and performance of course is the dance itself. Unwittingly I became involved in all of these many facetsof dance when I came from the US forfive months and stayed in Israel forfive years (1972-77). None of these facetswere clear cut and the diamond I thought I treasured and knew how to look at and teach had far more complexity, influences with boundaries blending differently than I had thought. Besides, what I had been taught as to how modem dance developed or what were differencesbetween types of dance had different bearings in this new country. My essay will synthesize dance informationand personal experiences including comments on Jewish identity while reporting on the ascension of modem dance and folkdance in Israel. It was only later as I began researching and writing about theatre dance and its development in Israel, that I came to realize as important were the living dance traditions in Jewish eydot (communities) and the relatively recent history of the creation of new Israeli folkdances. I came to see dance styles and personalities interacting in a much more profoundand influential way than I had ever expected. I was a studio trained ballet dancer, my teachers Ballets Russes alums Anna Adrianova and Lorand Andahazy; added to that, I studied modem dance at SarahLawrence College in New York. -

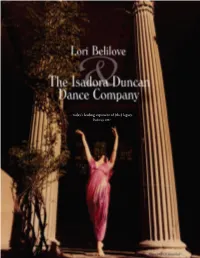

Today's Leading Exponent of (The) Legacy

... today’s leading exponent of (the) legacy. Backstage 2007 THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of that soul will have become the movement of the human body. The dancer will not belong to a nation but to all humanity. She will not dance in the form of nymph, nor fairy, nor coquette, but in the form of woman in her greatest and purest expression. From all parts of her body shall shine radiant intelligence, bringing to the world the message of the aspirations of thousands of women. She shall dance the freedom of women – with the highest intelligence in the freest body. What speaks to me is that Isadora Duncan was inspired foremost by a passion for life, for living soulfully in the moment. ISADORA DUNCAN LORI BELILOVE Table of Contents History, Vision, and Overview 6 The Three Wings of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation I. The Performing Company 8 II. The School 12 ISADORA DUNCAN DANCE FOUNDATION is a 501(C)(3) non-profit organization III. The Historical Archive 16 recognized by the New York State Charities Bureau. Who Was Isadora Duncan? 18 141 West 26th Street, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001-6800 Who is Lori Belilove? 26 212-691-5040 www.isadoraduncan.org An Interview 28 © All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation. Conceived by James Richard Belilove. Prepared and compiled by Chantal D’Aulnis. Interviews with Lori Belilove based on published articles in Smithsonian, Dance Magazine, The New Yorker, Dance Teacher Now, Dancer Magazine, Brazil Associated Press, and Dance Australia. -

Letter from the President

VOLUME 2, ISSUE 2 WINTER/SPRING 2006 UDEO NEWS LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT UDEO 2006 Conference Dubbed “Most Proactive Conference in the State! The UDEO 2006 Spring Conference Four Part Harmony and performances inspired us to reflect on ways personal heritage has been dubbed “the state’s most pro-active conference,” by Carol can influence our art-making. Now we have two more wonderful Ann Goodson, Utah State Office of Education Fine Arts Coordinator. UDEO sponsored events to unite and renew us. Her flattering statement piqued my curiosity and I asked her why Please accept a personal invitation to attend the UDEO/ she felt that way. “Because your members will - March forth on USOE day-long High School Dance Festival on February 25, March 4th!” she replied. Jean Irwin, arts education coordinator at at Bingham High School. This event concludes with an evening the Utah Arts Council added, “But your group will march forth…in concert that features the “best” high school choreography in the a dancerly way!” It’s a clever play on words yet I have come to state. Our Spring Conference, Four Part Harmony, with keynote realize that there is great truth in the observations of both Carol and presenter Alonzo King, a variety of professional development dance Jean. workshops, and a first of its kind panel presentation by members of This state is blessed with an abundance of excellent and our state legislature, school boards, and arts advocacy organizations pro-active dance and arts colleagues. Whether your dance interest will instruct and inspire us. If you share in the goal to increase lies in private or public dance education, professional or community quality dance opportunities in Utah, and enjoy the great connections, dance concerts and events, or you are the concerned parent of a child conversations, and of course great food that we always have at our who loves to dance, your membership and participation in UDEO Spring Conferences, then don’t forget to “March forth on March has real impact. -

State High School Dance Festival 2015

Utah Dance Education Organization State High School Dance Festival 2015 Adjudicator and Master Class Teacher Bios Ashley Anderson is a choreographer based in Salt Lake City. This summer she was awarded the Mayor’s Artist Award for Service to the Performing Arts at the Utah Arts Festival. Her recent dances have been presented locally at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center, the Rio Gallery, the BYU Museum of Art, Finch Lane Gallery, the City Library, the Utah Heritage Foundation’s Ladies’ Literary Club, the Masonic Temple and Urban Lounge as well as national venues including DraftWork at Danspace Project, Body- Blend at Dixon Place, Performance Mix at Joyce SOHO (NY); Mascher Space Cooperative, Crane Arts Gallery, the Arts Bank (PA); and the Taub- man Museum of Art (VA), among others. Her work was also presented by the HU/ADF MFA program at the American Dance Festival (NC) and the Kitchen (NY). She has recently performed in dances by Ishmael Houston- Jones, Regina Rocke & Dawn Springer. Teaching includes: the American Dance Festival Six & Four Week Schools, Hollins University, the University of Utah, Dickinson College Dance Theater Group, University of the Arts Con- tinuing Studies, Packing House Center for the Arts, the HMS School, the Virginia Tanner Dance Program, Salt Lake Community College and many high schools and community centers. Ashley currently di- rects “loveDANCEmore” community dance events using the resources of ashley anderson dances (a registered 501c3). Her projects with loveDANCEmore are also shared in Utah’s visual art magazine, 15 BYTES, where she serves as the dance editor. She holds B.A.s with honors in Dance and English from Hollins University as well as an M.F.A.