ECFG-Niger-May-19.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand

ICIP WORKING PAPERS: 2010/01 GRAN VIA DE LES CORTS CATALANES 658, BAIX 08010 BARCELONA (SPAIN) Territorial Autonomy T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | WWW.ICIP.CAT and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Territorial Autonomy and Self-Determination Conflicts: Opportunity and Willingness Cases from Bolivia, Niger, and Thailand Roger Suso Institut Català Internacional per la Pau Barcelona, April 2010 Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, 658, baix. 08010 Barcelona (Spain) T. +34 93 554 42 70 | F. +34 93 554 42 80 [email protected] | http:// www.icip.cat Editors Javier Alcalde and Rafael Grasa Editorial Board Pablo Aguiar, Alfons Barceló, Catherine Charrett, Gema Collantes, Caterina Garcia, Abel Escribà, Vicenç Fisas, Tica Font, Antoni Pigrau, Xavier Pons, Alejandro Pozo, Mònica Sabata, Jaume Saura, Antoni Segura and Josep Maria Terricabras Graphic Design Fundació Tam-Tam ISSN 2013-5793 (online edition) 2013-5785 (paper edition) DL B-38.039-2009 © 2009 Institut Català Internacional per la Pau · All rights reserved T H E A U T HOR Roger Suso holds a B.A. in Political Science (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, UAB) and a M.A. in Peace and Conflict Studies (Uppsa- la University). He gained work and research experience in various or- ganizations like the UNDP-Lebanon in Beirut, the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in Berlin, the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights to the Maghreb Elcàlam in Barcelona, and as an assist- ant lecturer at the UAB. An earlier version of this Working Paper was previously submitted in May 20, 2009 as a Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies in the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University, Swe- den, under the supervisor of Thomas Ohlson. -

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Narrative and Meaning of Sawaba's Rebellion in Niger

Sawaba's rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): narrative and meaning Walraven, K. van; Abbink, G.J.; Bruijn, M.E. de Citation Walraven, K. van. (2003). Sawaba's rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): narrative and meaning. In G. J. Abbink & M. E. de Bruijn (Eds.), African dynamics (pp. 218-252). Leiden: Brill. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12903 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12903 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 9 Sawaba’s rebellion in Niger (1964-1965): Narrative and meaning Klaas van Walraven One of the least-studied revolts in post-colonial Africa, the invasion of Niger in 1964 by guerrillas of the outlawed Sawaba party was a dismal failure and culminated in a failed attempt on the life of President Diori in the spring of 1965. Personal aspirations for higher education, access to jobs and social advancement, probably constituted the driving force of Sawaba’s rank and file. Lured by the party leader, Djibo Bakary, with promises of scholarships abroad, they went to the far corners of the world, for what turned out to be guerrilla training. The leadership’s motivations were grounded in a personal desire for political power, justified by a cocktail of militant nationalism, Marxism-Leninism and Maoist beliefs. Sawaba, however, failed to grasp the weakness of its domestic support base. The mystifying dimensions of revolutionary ideologies may have encouraged Djibo to ignore the facts on the ground and order his foot soldiers to march to their deaths. -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Ve 1.2) Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/03/2018 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 06/05/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 09/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V. 1 . 2 2 NIGER Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Eric REPETTO and Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1Country in Brief 1.2Modern and Contemporary History of Niger 1.3 Geography 1.4Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7Health 1.8Education and Literacy 1.9Country Economy 2. -

The Emergence of Hausa As a National Lingua Franca in Niger

Ahmed Draia University – Adrar Université Ahmed Draia Adrar-Algérie Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Letters and Language A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Master’s Degree in Linguistics and Didactics The Emergence of Hausa as a National Lingua Franca in Niger Presented by: Supervised by: Moussa Yacouba Abdoul Aziz Pr. Bachir Bouhania Academic Year: 2015-2016 Abstract The present research investigates the causes behind the emergence of Hausa as a national lingua franca in Niger. Precisely, the research seeks to answer the question as to why Hausa has become a lingua franca in Niger. To answer this question, a sociolinguistic approach of language spread or expansion has been adopted to see whether it applies to the Hausa language. It has been found that the emergence of Hausa as a lingua franca is mainly attributed to geo-historical reasons such as the rise of Hausa states in the fifteenth century, the continuous processes of migration in the seventeenth century which resulted in cultural and linguistic assimilation, territorial expansion brought about by the spread of Islam in the nineteenth century, and the establishment of long-distance trade by the Hausa diaspora. Moreover, the status of Hausa as a lingua franca has recently been maintained by socio- cultural factors represented by the growing use of the language for commercial and cultural purposes as well as its significance in education and media. These findings arguably support the sociolinguistic view regarding the impact of society on language expansion, that the widespread use of language is highly determined by social factors. -

Surveillance in Niger : Gendarmes and the Problem of "Seeing Things"

Erschienen in: African Studies Review ; 59 (2016), 2. - S. 39-57 https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/asr.2016.37 Surveillance in Niger: Gendarmes and the Problem of “Seeing Things” Mirco Göpfert Abstract: Today, high-tech surveillance seems omnipresent in Niger, particularly because of the conflicts in neighboring Mali, Libya, and Nigeria and efforts by the U.S. and France to boost local security agencies. However, Niger is not a very efficient “registering machine,” and the gendarmes have very limited knowledge of the com- munities in which they work. The key to overcoming this problem of knowledge—to “see things,” as the gendarmes put it—is the nurturing of good relationships with potential informants. But as the gendarmes depend on the knowledge of locals, the power relationship between the surveillers and those observed proves far more ambiguous than generally assumed. Résumé: Aujourd’hui, au Niger, une surveillance de haute technologie semble omniprésente, en particulier à cause des conflits au Mali, en Libye et au Niger et des efforts soutenus des États-Unis et de la France pour renforcer les agences de sécurité locales. Cependant, le Niger n’est pas une “machine d’enregistrement,” très efficace et les gendarmes ont une connaissance très limitée des communautés dans lesquelles ils travaillent. La clé pour surmonter ce problème réside dans “la manière de voir les choses,” comme les gendarmes le disent, c’est-à-dire d’entretenir de bonnes relations avec les informateurs potentiels. Mais comme les gendarmes dépendent de la connaissance de la population locale, le rapport de force entre les surveillés et les surveillants prouve être beaucoup plus ambigu que générale- ment présumé. -

ECFG-Niger-2020R.Pdf

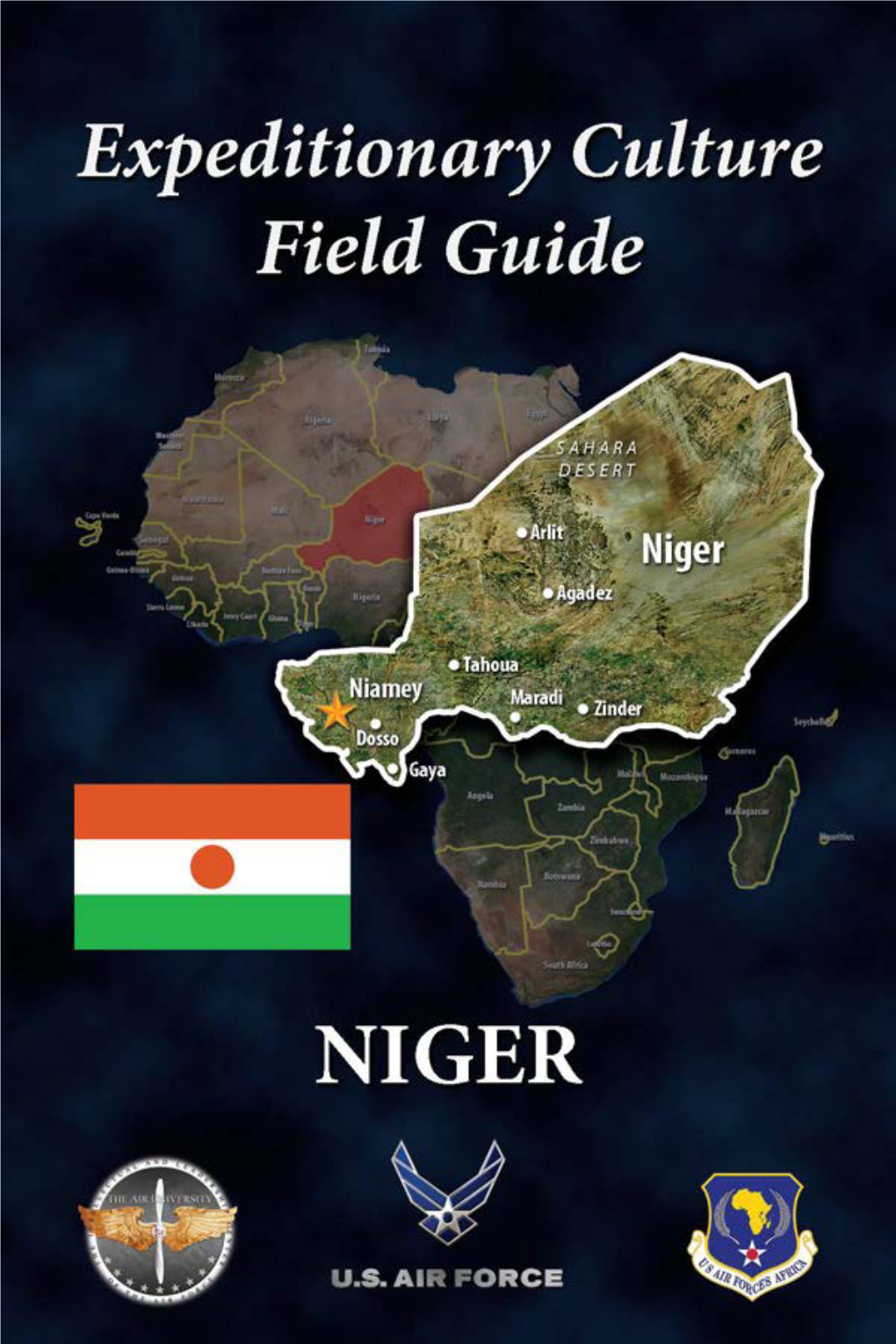

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment (Photos courtesy of IRIN News 2012 © Jaspreet Kindra). Niger Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Niger, focusing on unique cultural features of Nigerien society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Islam in Medieval West Africa

Name: Date: ISLAM IN MEDIEVAL WEST AFRICA Written by Amina Brown 1010L-1200L Trans-Saharan trade brought Islam to West Africa in the 8th century. At first, Muslim traders and merchants lived side by side with non-Muslims of West Africa. Over time, however, Islam played a growing role in West African society. Today, almost one-third of the world’s Muslim population resides in Africa. The first West Africans to be converted were the inhabitants of the Sahara, the Berbers, and it is generally agreed that by the second half of the tenth century, the Sahara had become Dar al- Islam, that is “the country of Islam.” West Africans often blended Islamic culture with their own traditions. For example, West Africans who became Muslims began praying to God in Arabic. They built mosques as places of worship. Yet they also continued to pray to the spirits of their ancestors, as they had done for centuries. During the Medieval period, empires with complex political structures and social orders emerged in Sub-Saharan Africa. In West Africa, three of such empires evolved in the Savanna and Sahel zones. The Sudanic empires, namely, GHANA, ( 700-1070 AD), MALI, (1230-1430 AD), and SONGHAI (1460-1590 AD) overlapped each other. Islam in Ghana Between the years 639 and 708 C.E., Arab Muslims conquered North Africa. Before long, they wanted to bring West Africa into the Islamic world. But sending armies to conquer Ghana was not practical. Ghana was too far away, and it was protected by the Sahara. Islam first reached Ghana through Muslim traders and missionaries. -

Sketch-Map Illustrating the Special Agreement Seising the International Court of Justice

- 96 - Sketch-map illustrating the Special Agreement seising the International Court of Justice Tillabéry Tripoint a and b: sectors agreed between the Parties 1 and 2: sectors disputed by the Parties 1: Téra sector 2: Say sector Tripoint: meeting point of Tillabéry, Say and Dori cercles This sketch-map is for illustrative purposes only 4 February 2011 - 97 - 7.6. The area is characterized by the presence of abundant wildlife. Its southern part includes one of the most important wildlife reserves in West Africa: the Niger W Regional Park 291 , which covers 1 million hectares on the territories of Niger, Burkina Faso and Benin. Outside the area of the park, towards the River Sirba, herds of elephant, buffalo and warthog can be met with, as well as groups of lion, hyena and leopard, which makes the conduct of human activity problematic in the area. The region’s watercourses and pools were long infested with tsetse flies, causing blindness among humans and animals. This parasite was eradicated several decades ago. But previously, the presence of tsetse fly and poisonous snakes resulted in the relocation of many villages, or even their disappearance. 7.7. In human terms, the Say/Fada region is lightly populated. It is subject to constant regional transhumance. This is of three kinds: major transhumance, which consists of movements over very long distances, generally practiced by the Bororo and related Peulhs; minor transhumance, a movement over short and medium distances, generally carried out in order to exploit the pastureland beside rivers and pools; commercial transhumance, involving small flocks, for the purpose of increasing milk production and taking advantage of the pasturage provided by fallow croplands. -

The 5Th Francophonie Sports and Arts Festival: Niamey, Niger Hosts a Global Community

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 10, Issues 2 & 3 | Fall 2008 The 5th Francophonie Sports and Arts Festival: Niamey, Niger Hosts a Global Community SCOTT M. YOUNGSTEDT Abstract: This paper explores transnational and local cultural, political, and economic dimensions of the 5th Jeux de la Francophonie (“Francophonie Games” or “Francophonie Sports and Arts Festival”) held in Niamey, Niger in December 2005. The Jeux were designed to promote peace, solidarity, and cultural exchange through sports and the arts. This paper focuses on the kinds of discourses that were represented and celebrated in the social and political arena of the Jeux. It aims to contribute to the discussion of (1) the politics of Francophonie concept, (2) the negotiation of local and global politics in the context of major sports and arts events, and (3) the representation of local, national, and global politics in public ceremonies. The Francophonie Community Seeks Solidarity through the Universal Languages of Sports and Arts This paper explores transnational and local cultural, political, and economic dimensions of the 5th Jeux de la Francophonie (“Francophonie Games” or “Francophonie Sports and Arts Festival”) held in Niamey, Niger in December 2005.1 Approximately 2,500 athletes and artists, and hundreds of their coaches representing 44 member nations of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) competed in seven sports (track and field, basketball, boxing, soccer, judo, African wrestling, and table tennis) and seven arts (singing, oral storytelling, literature, dancing, painting, photography, and sculpture). While all participants in the Jeux reside in member nations of the OIF, choices of athletes and artists were based on the excellence of their performance and not on French literacy.