Aviation Consumer Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portola Valley Aircraft Noise Monitoring

Portola Valley Aircraft Noise Monitoring Prepared by San Francisco International Airport Aircraft Noise Abatement Office Technical Report #012017-978 January 2017 San Francisco International Airport Portola Valley Aircraft Noise Monitoring Report Page | 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 3 Community and SFO Operations............................................................................................................ 3 Equipment ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Aircraft Noise Analysis........................................................................................................................... 4 Aircraft Operations ................................................................................................................................. 6 Track Density.......................................................................................................................................... 8 Noise Reporters....................................................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Figure 1 ................................................................................................................................................ -

Scottsdale Airport Advisory Commission Meeting Notice and Agenda

SCOTTSDALE AIRPORT ADVISORY COMMISSION MEETING NOTICE AND AGENDA Wednesday, June 16, 2021 5:00 p.m. Meeting will be held electronically and remotely AIRPORT ADVISORY COMMISSION John Berry, Chair Cory Little Charles McDermott Vice-Chair Peter Mier Larry Bernosky Rick Milburn Ken Casey Until further notice, Airport Advisory Commission meetings are being held electronically. While physical facilities are not open to the public, Airport Advisory Commission meetings are available on Scottsdale’s YouTube channel to allow the public to virtually attend and listen/view the meeting in progress. 1. Go to ScottsdaleAZ.gov, search “live stream” 2. Click on “Scottsdale YouTube Channel” 3. Scroll to “Upcoming live streams” 4. Select the applicable meeting Spoken comment is being accepted on agenda action items. To sign up to speak on these please click here. Request to speak forms must be submitted no later than 90 minutes before the start of the meeting. Written comment is being accepted for both agendized and non-agendized items, and should be submitted electronically no later than 90 minutes before the start of the meeting. To submit a written public comment electronically, please click here Call to Order Roll Call Aviation Director’s Report The public body may not propose, discuss, deliberate or take legal action on any matter in the summary unless the specific matter is properly noticed for legal action. 18894560-v1 Approval of Minutes Regular Meeting: May 19, 2021 REGULAR AGENDA ITEMS 1-9 How the Regular Agenda Works: The Commission takes a separate action on each item on the Regular Agenda 1. Discussion and Possible Action regarding application for Airport Aeronautical Business Permit for C. -

1980 Cessna Skymaster

1980 Cessna Skymaster • Purchased in 1987 for $83,500 • Sold in 2011 for $109,600 • Purpose- airport inspections, • transportation • Flight Hours- - 2011 122 hours (thru Sept) - 2010 224 hours - 2009 144 hours - 2008 172 hours - 2007 229 hours • Maintenance Costs (see supplemental sheet) • Cost per flight hour $430 including reserves • Strengths- efficient, good overhead visibility • Limitations- known icing, small and soft runways • Reason for replacement- beyond useful service life )> '"U '"Um z 0 >< c.... 1980 Cessna 337 Skymaster 08/21/09 $1,523.77 3095.5 3102.2 07/20/10 $627.58 $1,618.7 6130 r-------~-------1 1952 : r-------~------~ 6153 ' r-------~------~ 9563 3111.1 243.56 gear 6177 ' 5,905.00 insurance-year 3123.5 168.26 window release 6206 6187 1980 Cessna 337 Skymas,ter A B C D E G H j__ ;~t1~':_!L·:.t;~~t~~.rcl~~:~~,g~Jf!e!~:tit.i:Q)~j;ih;2~~~§ia!fJ~~'~g~·.~~.~~§~,·;1~1{~.~~;,}~ '{ifit···:·· ''.. :.''·eu~J,;~;f3}~;~~t~~dWi~,}i~ 4 ~ 1 Hobbs Amount Description 1 WO # Date Amount , 48 10/14/10 I 3180.9 280.00 autopilot 10251 49 10/13/10 3182.5 383.47 tires 6297 50 10/21/10 3218.8 · 1,789.24 vacuum pumps 6319 51 10/26/10 3221.5 7,888.31 deice system 6311 10/12/10 $152.79 52 11/4/10 3224.5 92.91 deice system 6344 11/05/10 $9,929.18 53 10/28/10 3230.0 474.03 prop synch, cowl flap 6330 11/09/10 $7,994.73 54 11/8/10 3232.2 584.16 oil change, fuel strain 6349 10/15/10 $305.77 55 11/19/10 3234.6 84.24 tanis heater 6376 11/20/10 $711.97 ~~~~~-+--~--4 56 11/23/10 3234.6 609.47 prop synch 6381 11/30/10 $525.59 57 11/24/10 4.75 chart 12/31/10 $791.44 58 12/7/10 3237.1 964.00 prop deice 22946 12/31/10 $560.00 !~~~---+--~--~ 59 12/9/10 3237.1 3,258.10 H.S.I. -

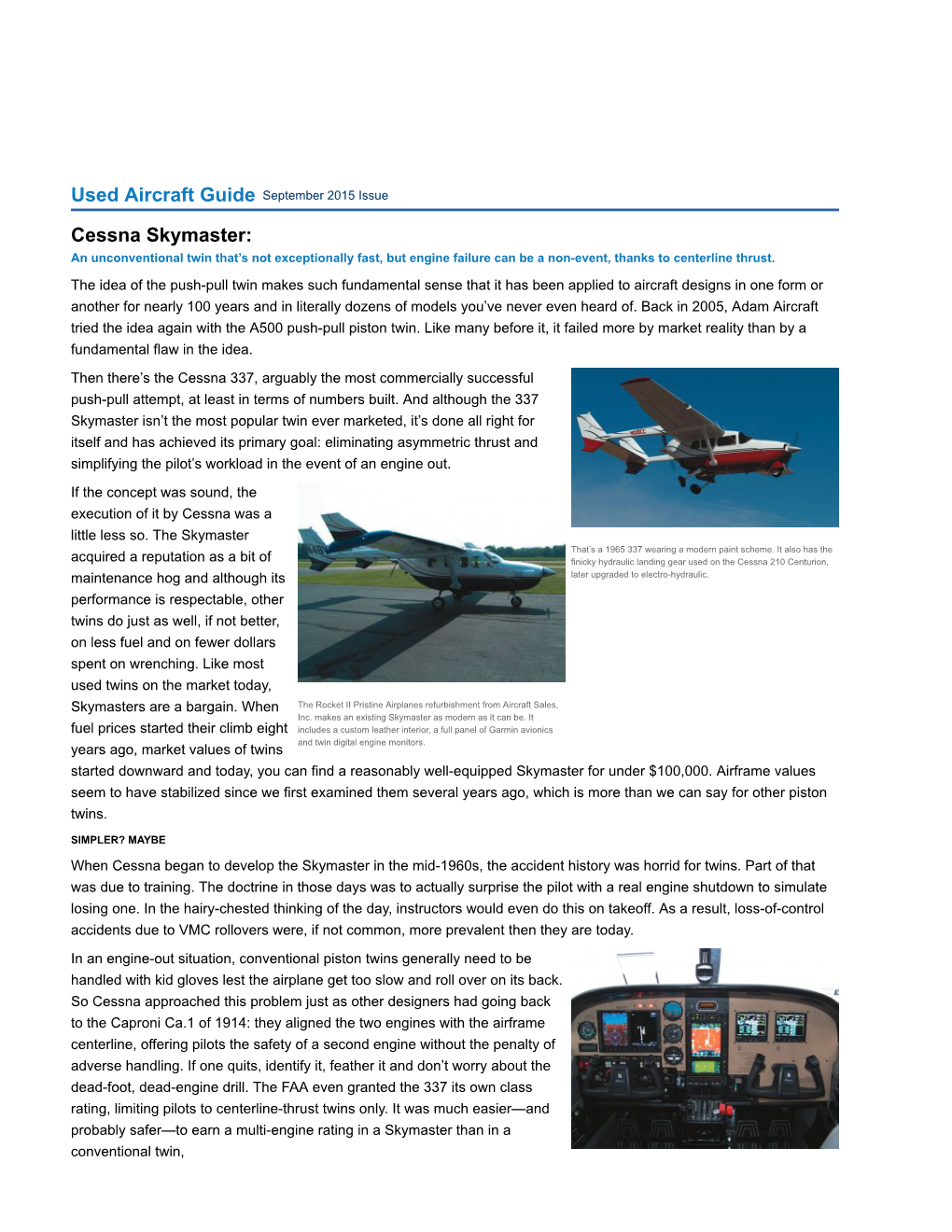

Cessna Skymaster: It May Not Be a Speed Demon and It’S Definitely an Unconventional Twin, but Cessna’S Push-Pull Model 337 Is a Lot of Airplane for the Money

USED AIRCRAFT GUIDE Cessna Skymaster: It may not be a speed demon and it’s definitely an unconventional twin, but Cessna’s push-pull model 337 is a lot of airplane for the money. he Cessna 337 Skymaster is ar- ity than by a fundamental flaw in the have stabilized since we first exam- guably the most commercially idea. We really wanted that one to work. ined them several years ago, which Tsuccessful so-called push-pull If the push-pull concept was is more than we can say for other attempt, at least in terms of numbers seamless, the execution of it by piston twins. built. And although the 337 Skymas- Cessna was a little less so. The Sky- ter isn’t the most popular twin ever master acquired a reputation as a bit NOT REALLY SIMPLER marketed, it’s done just fine for itself of a maintenance hog and although When Cessna began to develop and has achieved its primary goal: its performance is respectable, other the Skymaster in the mid-1960s, eliminating asymmetric the accident history thrust and simplifying was horrid for twins. the pilot’s workload in Part of that was due to the event of an engine A potential Skymaster ownership training. The doctrine out. Unfortunately, as in those days was to you’ll see in our ac- nightmare is runaway maintenance actually surprise the cident scan on page 30, pilot with a real engine some Skymaster pilots costs, especially in pressurized models. shutdown to simulate find plenty of other losing one. In the hairy- ways to NTSB fame. -

Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel by Kerwin Mckenzie

McKenzie Ultimate Guides: A Guide to Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel By Kerwin McKenzie McKenzie Ultimate Guides: Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel Copyright Normal copyright laws are in effect for use of this document. You are allowed to make an unlimited number of verbatim copies of this document for individual personal use. This includes making electronic copies and creating paper copies. As this exception only applies to individual personal use, this means that you are not allowed to sell or distribute, for free or at a charge paper or electronic copies of this document. You are also not allowed to forward or distribute copies of this document to anyone electronically or in paper form. Mass production of paper or electronic copies and distribution of these copies is not allowed. If you wish to purchase this document please go to: http://www.passrider.com/passrider-guides. First published May 6, 2005. Revised May 10, 2005. Revised October 25, 2009. Revised February 3, 2010. Revised October 28, 2011. Revised November 26 2011. Revised October 18 2013. © 2013 McKenzie Ultimate Guides. All Rights Reserved. www.passrider.com © 2013 – MUG:NRSA Page 1 McKenzie Ultimate Guides: Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel Table of Contents Copyright ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 About the Author ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Air Taxi SOLUTIONS GLENAIR

GLENAIR • JULY 2021 • VOLUME 25 • NUMBER 3 LIGHTWEIGHT + RUGGED Interconnect AVIATION-GRADE Air Taxi SOLUTIONS GLENAIR Transitioning to renewable, green-energy fuel be harvested from 1 kilogram of an energy source. would need in excess of 6000 Tons of battery power much of this work includes all-electric as well as sources is an active, ongoing goal in virtually every For kerosene—the fuel of choice for rockets and to replace its 147 Tons of rocket fuel. And one can hybrid designs that leverage other sources of power industry. While the generation of low-carbon- aircraft—the energy density is 43 MJ/Kg (Mega only imagine the kind of lift design that would be such as small form-factor kerosene engines and footprint energy—from nuclear, natural gas, wind, Joules per kilogram). The “energy density” of the required to get that baby off the ground. hydrogen fuel cells. and solar—might someday be adequate to meet our lithium ion battery in the Tesla, on the other hand, And therein lies the challenge for the nascent air Indeed, it may turn out that the most viable air real-time energy requirements, the storage of such is about 1 MJ/kg—or over 40 times heavier than jet taxi or Urban Air Mobility (UAM) industry. In fact, the taxi designs are small jet engine configurations energy for future use is still a major hurdle limiting fuel for the same output of work. And yet the battery only realistic circumstance in which eVTOL air taxis augmented with backup battery power, similar in the wholesale shift to renewable power. -

FY 2000 Aviation Safety Summary

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service FY 2000 Aviation Summary Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Overview of the Forest Service Aviation Program 2 Statistical Summary 4 USFS Owned Aircraft Statistics 10 Fixed-Wing Statistics 12 Airtanker Statistics 14 Helicopter Statistics 16 Benchmarks with other Organizations 18 Smokejumper Program Overview 21 SafeCom Summary 25 Accident Summary 35 Airwards 40 NOTE: Formulas used: Industry standard “per 100,000 hours flown” Accident Rate = Number of accidents divided by the number of hours flown. Fatal Accident Rate = Number of fatal accidents divided by the number of hours flown. Fatality Rate = Number of fatalities divided by the number of hours flown. Executive Summary It would be an understatement to say that the year 2000 was a high effort year for Forest Service aviation. An analysis of all available statistical data shows that the 111,486 flight hours flown in one year is the second most in history. The overall mishap rate of 3.58 stands as a new benchmark for years of this magnitude. The average mishap rate for fire years with greater than 90,000 hours flown is 10.90 and the previous best mark in a large year was 8.40. The following report shows two very positive safety trends in Forest Service aviation safety over the past ten years. 1. Lower mishap rates across the board. 2. Increased utilization of our incident reporting system (SafeComs). Other key points to consider when looking at the following statistical summaries include: ü Helicopters provide nearly 50% of the overall aviation effort and operate in the most challenging risk areas (long line, rappel, bucket work, etc.) ü Contractors provide nearly 90% of our overall aviation production ü Statistically, our most hazardous operations, as determined by the 10-year average mishap rate (1991-2000) are: 1. -

99 News Letters; the Struction Offers Tremendous Promise for Batavia, Ohio 45103 American Weekly, July 19, 1953; Jean Achieving That Goal

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS SSmus In This Issue: 99s — What It Means ty - heme of WACOA Fall Meeting d News From Beech re To Fly ff it w S S n E iu s Spotlighting JANUARY 1973 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 1 THE NINETY-NINES, INC. Will Rogers World Airport The International Headquarters Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 International President Return Form 3579 to above address 2nd Class Postage pd. at North Little Rock. Ark. It is November 17th and the fog is thick this morning as P u b lis h e r......................................... Lee Keenihan I look out the window here in Sacramento, California. Managing Editor ...........................Mardo Crane The gray skies are predicted to clear soon for the mem Assistant Editor ...............................Betty Hicks bers flying in for the 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Art Director.................................... Lucille Nance Sacramento Valley Chapter. Several happy faces greeted Production Manager Ron Oberlag us at the airport on our arrival in the rain last night and we Circulation Manager................... Loretta Gragg chatted while we waited for the luggage to come off the big DC-8. Broneta Davis Evans (past president) had flown Contributing Editors Gene FitzPatrick out with me and we were enjoying ourselves visiting with •'Wally" Funk Darlene Gilmore, Gerry Mickelson (also a past president), Virginia Thompson Barbara Goetz, Barbara Foster, Shirley and Ernie Lehr. Director of Advertising ...................Paula Reed Then the moment of realization finally arrived — like the Susie Sewell head-on collision which only happens to other people — our luggage didn’t show up, so obviously it didn't get on the plane at Los Angeles. -

Codebook (PDF Format)

INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM: ATTRIBUTES OF TERRORIST EVENTS ITERATE 1968-2020 DATA CODEBOOK Compiled by Edward F. Mickolus Todd Sandler Jean M. Murdock Peter A. Flemming Last Update June 2020 The ITERATE project is an attempt to quantify data on the characteristics of transnational terrorist groups, their activities which have international impact, and the environment in which they operate. ITERATE 3 and 4 update the coverage of terrorist incidents first reported in ITERATE 1 and 2, which can be obtained from the Inter- University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Box 1248, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. ITERATE 3 and 4 are compatible with the coding categories used in its predecessors, but includes new variables. The working definition of international/transnational terrorism used by the ITERATE project is the use, or threat of use, of anxiety-inducing, extra-normal violence for political purposes by any individual or group, whether acting for or in opposition to established governmental authority, when such action is intended to influence the attitudes and behavior of a target group wider than the immediate victims and when, through the nationality or foreign ties of its perpetrators, its location, the nature of its institutional or human victims, or the mechanics of its resolution, its ramifications transcend national boundaries. International terrorism is such action when carried out by individuals or groups controlled by a sovereign state, whereas transnational terrorism is carried out by basically autonomous non-state actors, whether or not they enjoy some degree of support from sympathetic states. "Victims" are those individuals who are directly harmed by the terrorist incident. -

Modernização Da Força Aérea Moçambicana: Formação, Aquisições, Cooperação E Desafios Estratégicos

REVISTA DEFESA E SEGURANÇA V. 2 (2016) 123 Modernização da Força Aérea Moçambicana: Formação, Aquisições, Cooperação e Desafios Estratégicos. Emílio Jovando Zeca 1 Resumo O presente artigo tem como objetivo central analisar os elementos da requalificação e modernização da Força Aérea Moçambicana, diante dos desafios estratégicos nacionais moçambicanos. A Força Aérea Moçambicana é um dos três ramos das Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique, que, para além das missões gerais das Forças Armadas partilhadas com outros ramos, realiza ações aéreas, no solo ou em cooperação, necessárias à defesa da nação e aos interesses e objetivos nacionais. Com o fim da Guerra dos 16 anos e a assinatura dos Acordos Gerais de Paz, em 1992, a Força Aérea de Moçambique ficou quase inativa, por motivos pouco divulgados. Enquanto uns apontam como razão central o colapso da URSS, seu antigo parceiro estratégico, outros apontam para um consenso entre os signatários dos Acordos de Paz – Governo de Moçambique e a Resistência Nacional de Moçambique – a fim de desativar este ramo das Forças Armadas. Todavia, nos últimos tempos, verifica-se um conjunto de démarches políticas e militares no intuito de requalificar e modernizar a Força Aérea Moçambicana. O estudo baseou-se numa metodologia assentada no método histórico, observação direta e pesquisa bibliográfica e conclui que a formação, as aquisições e cooperação técnico-militar bilateral e multilateral se afiguram como as principais estratégias de atuação para que os primeiros passos da reestruturação, requalificação e modernização possam ser dados e a Força Aérea Moçambicana possa executar a sua missão de forma efetiva, diante dos desafios estratégicos presentes e futuros. -

215183076.Pdf

IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM TRENDS ON AERONAUTICAL SECURITY By CHRIS ANTHONY HAMILTON Bachelor of Science Saint Louis University Saint Louis, Missouri 1987 Master of Science Central Missouri State University Warrensburg, Missouri 1991 Education Specialist Central Missouri State University Warrensburg, Missouri 1994 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1996 COPYRIGHT By Chris Anthony Hamilton May, 1996 IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM TRENDS ON AERONAUTICAL SECURITY Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere appreciation to all those who, support, guidance, and sacrificed time made my educational experience at Oklahoma State University a successful one. First, I would like to thank my doctoral committee chairman, Dr. Cecil Dugger for his guidance and direction throughout my doctoral program. Dr. Dugger is a unique individual for which I have great respect not only as a mentor but also as good and supportive friend. I would also like to thank my dissertation advisor Dr. Steven Marks, for his support and impute in my academic life at Oklahoma State University. I would also like to thank the Dr. Kenneth Wiggins, Head, Department of Aviation and Space Education for his continue and great support in many ways, that without, I will have never completed my educational goals. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Deke Johnson as my doctoral committee member, that has always a kind and wise word to get me through difficult days. -

Volume III: Marine Mammal and Sea Turtles Studies

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Baseline Studies Final Report Volume III: Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Studies Geo-Marine, Inc. 2201 K Avenue, Suite A2 Plano, Texas 75074 July 2010 JULY 2010 NJDEP EBS FINAL REPORT: VOLUME III TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... ix LIST OF METRIC TO U.S. MEASUREMENT CONVERSIONS ................................................................. xi 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 PREVIOUS STUDIES ............................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 BASELINE STUDY OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................ 1-2 2.0 AERIAL AND SHIPBOARD SURVEY METHODOLOGY ............................................................ 2-1 2.1 AERIAL SURVEY DESIGN ..................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.1 Survey Effort ......................................................................................................