Renal and Adrenal Tumours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adrenal Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Adrenal

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Adrenal Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Learn more about the risk factors for adrenal cancer. ● Adrenal Cancer Risk Factors ● What Causes Adrenal Cancer? Prevention Since there are no known preventable risk factors for this cancer, it is not possible to prevent this disease. Adrenal Cancer Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that changes your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed. Scientists have found few risk factors that make a person more likely to develop adrenal cancer. Even if a patient does have one or more risk factors for adrenal cancer, it is impossible to know for sure how much that risk factor contributed to causing the cancer. 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. Many people with risk factors never develop adrenal cancer, while others with this disease may have few or no known risk factors. Genetic syndromes The majority of adrenal cortex cancers are not inherited (sporadic), but some (up to 15%) are caused by a genetic defect. This is more common in adrenal cancers in children. Li-Fraumeni syndrome The Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare condition that is most often caused by a defect in the TP53 gene. -

Endocrine Pathology (537-577)

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION THE BASIC AND TRANSLATIONAL PATHOLOGY RESEARCH JOURNAL LI VOLUME 99 | SUPPLEMENT 1 | MARCH 2019 2019 ABSTRACTS ENDOCRINE PATHOLOGY (537-577) MARCH 16-21, 2019 PLATF OR M & 2 01 9 ABSTRACTS P OSTER PRESENTATI ONS EDUCATI ON C O M MITTEE Jason L. Hornick , C h air Ja mes R. Cook R h o n d a K. Y a nti s s, Chair, Abstract Revie w Board S ar a h M. Dr y and Assign ment Co m mittee Willi a m C. F a q ui n Laura W. La mps , Chair, C ME Subco m mittee C ar ol F. F ar v er St e v e n D. Billi n g s , Interactive Microscopy Subco m mittee Y uri F e d ori w Shree G. Shar ma , Infor matics Subco m mittee Meera R. Ha meed R aj a R. S e et h al a , Short Course Coordinator Mi c h ell e S. Hir s c h Il a n W ei nr e b , Subco m mittee for Unique Live Course Offerings Laksh mi Priya Kunju D a vi d B. K a mi n s k y ( Ex- Of ici o) A n n a M ari e M ulli g a n Aleodor ( Doru) Andea Ri s h P ai Zubair Baloch Vi nita Parkas h Olca Bast urk A nil P ar w a ni Gregory R. Bean , Pat h ol o gist-i n- Trai ni n g D e e p a P atil D a ni el J. -

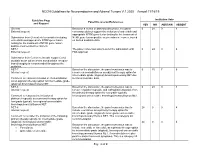

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19

NCCN Guidelines for Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors V.1.2020 – Annual 11/18/19 Guideline Page Institution Vote Panel Discussion/References and Request YES NO ABSTAIN ABSENT General Based on a review of data and discussion, the panel 0 24 0 4 External request: consensus did not support the inclusion of entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion testing for the treatment of Submission from Genentech to consider including NTRK gene fusion-positive neuroendocrine cancer, based entrectinib and appropriate NTRK gene fusion on limited available data. testing for the treatment of NTRK gene fusion- positive neuroendocrine cancers. NET-1 The panel consensus was to defer the submission until 0 24 0 4 External request: FDA approval. Submission from Curium to include copper Cu 64 dotatate as an option where somatostatin receptor- based imaging is recommended throughout the guideline. NET-7 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 15 7 6 Internal request: remove chemoradiation as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET due Comment to reassess inclusion of chemoradiation to limited available data. as an adjuvant therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical) bronchopulmonary NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 0 24 0 4 Internal request: remove cisplatin/etoposide and carboplatin/etoposide from the primary therapy option for low grade (typical), Comment to reassess the inclusion of locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. platinum/etoposide as a primary therapy option for low grade (typical), locoregional unresectable bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. NET-8 Based on the discussion, the panel consensus was to 24 0 0 4 Internal request: include everolimus as a primary therapy option for intermediate grade (atypical), locoregional unresectable Comment to consider the inclusion of the following bronchopulmonary/thymus NET. -

Primary Renal Carcinoid Tumor: a Radiologic Review

Radiology Case Reports Volume 9, Issue 2, 2014 Primary renal carcinoid tumor: A radiologic review Leslie Lamb, MD, Msc, Bsc; Wael Shaban, MBBCH, MD, PhD Carcinoid tumor is the classic famous anonym of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Primary renal carcinoid tumors are extremely rare, first described by Resnick and colleagues in 1966, with fewer than a total of 100 cases reported in the literature. Thus, given the paucity of cases, the clinical and histological behav- ior is not well understood, impairing the ability to predict prognosis. Computed tomography and (occa- sionally) octreotide studies are used in the diagnosis and followup of these rare entites. A review of 85 cases in the literature shows that no distinctive imaging features differentiate them from other primary renal masses. The lesions tend to demonstrate a hypodense appearance and do not usually enhance in the arterial phases, but can occasionally calcify. Octreotide scans do not seem to help in the diagnosis; however, they are more commonly used in the postoperative followup. In addition, we report a new case of primary renal carcinoid in a horseshoe kidney. Case report Imaging findings 40-year-old male initially presented to a community hos- pital with a 20-lb weight loss over a few months. In retro- CT of the abdomen and pelvis, done in the portal ve- spect, the patient recalled mild left-flank discomfort and nous phase, demonstrated a solid, hypodense, 4.5-cm renal fatigue, but denied any hematuria. Blood work revealed an mass containing calcifications, located in the posterior as- elevated serum glucose, and he was diagnosed with type 2 pect of the medial diabetes. -

Neoplastic Metastases to the Endocrine Glands

27 1 Endocrine-Related A Angelousi et al. Metastases to endocrine 27:1 R1–R20 Cancer organs REVIEW Neoplastic metastases to the endocrine glands Anna Angelousi1, Krystallenia I Alexandraki2, George Kyriakopoulos3, Marina Tsoli2, Dimitrios Thomas2, Gregory Kaltsas2 and Ashley Grossman4,5,6 1Endocrine Unit, 1st Department of Internal Medicine, Laiko Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 2Endocrine Unit, 1st Department of Propaedeutic Medicine, Laiko University Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece 3Department of Pathology, General Hospital ‘Evangelismos’, Αthens, Greece 4Department of Endocrinology, OCDEM, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK 5Neuroendocrine Tumour Unit, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK 6Centre for Endocrinology, Barts and the London School of Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK Correspondence should be addressed to A Angelousi: [email protected] Abstract Endocrine organs are metastatic targets for several primary cancers, either through Key Words direct extension from nearby tumour cells or dissemination via the venous, arterial and f glands lymphatic routes. Although any endocrine tissue can be affected, most clinically relevant f cancer metastases involve the pituitary and adrenal glands with the commonest manifestations f metastases being diabetes insipidus and adrenal insufficiency respectively. The most common f pituitary primary tumours metastasing to the adrenals include melanomas, breast and lung f adrenal carcinomas, which may lead to adrenal insufficiency in the presence of bilateral adrenal f thyroid involvement. Breast and lung cancers are the most common primaries metastasing to f ovaries the pituitary, leading to pituitary dysfunction in approximately 30% of cases. The thyroid gland can be affected by renal, colorectal, lung and breast carcinomas, and melanomas, but has rarely been associated with thyroid dysfunction. -

Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion

Published online: 2021-05-24 Practitioner Section Solitary Duodenal Metastasis from Renal Cell Carcinoma with Metachronous Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: Review of Literature with a Case Discussion Abstract Saphalta Baghmar, Renal cell cancinoma (RCC) is a unique malignancy with features of late recurrences, metastasis S M Shasthry1, to any organ, and frequent association with second malignancy. It most commonly metastasizes Rajesh Singla, to the lungs, bones, liver, renal fossa, and brain although metastases can occur anywhere. RCC 2 metastatic to the duodenum is especially rare, with only few cases reported in the literature. Herein, Yashwant Patidar , 3 we review literature of all the reported cases of solitary duodenal metastasis from RCC and cases Chhagan B Bihari , of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) as synchronous/metachronous malignancy with RCC. Along with S K Sarin1 this, we have described a unique case of an 84‑year‑old man who had recurrence of RCC as solitary Departments of Medical duodenal metastasis after 37 years of radical nephrectomy and metachronous pancreatic NET. Oncology, 1Hepatology, 2Radiology and 3Pathology, Keywords: Late recurrence, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, renal cell carcinoma, second Institute of Liver and Biliary malignancy, solitary duodenal metastasis Sciences, New Delhi, India Introduction Case Presentation Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is unique An 84‑year‑old man with a medical history to have many unusual features such as notable for hypertension and RCC, 37 years metastasis to almost every organ in the body, postright radical nephrectomy status, late recurrences, and frequent association presented to his primary care physician with second malignancy. The most common with fatigue. When found to be anemic, sites of metastasis are the lung, lymph he was treated with iron supplementation nodes, liver, bone, adrenal glands, kidney, and blood transfusions. -

A Case of Postpartum Hypopituitarism Accompanied by Cushing's

Endocrine Journal 2005, 52 (2), 219–222 A Case of Postpartum Hypopituitarism Accompanied by Cushing’s Syndrome as a Result of an Adrenocortical Carcinoma MEHMET SENCAN AND HATICE SEBILA DOKMETAS* Department of Hematology, Faculty of Medicine, Cumhuriyet University, 58140 Sivas, Turkey *Department of Endocrinology, Faculty of Medicine, Cumhuriyet University, 58140 Sivas, Turkey Abstract. Sheehan’s syndrome frequently causes hypopituitarism either immediately or after a delay of several years, depending on the degrees of postpartum ischemic pituitary necrosis. A 55 year-old woman whose last child was born 27 yr ago with massive hemorrhage was diagnosed as postpartum hypopituitarism. She had deficiency of growth hormone, prolactin, gonadotropins and thyrotropin. However, she interestingly had apparent hypercortisolism without suppression response to the dexamethasone tests. We found an adrenal mass with distant metastases to the liver and lung while investigating the origin of the hypercortisolism. Hyperandrogenism and very high levels of 17 hydroxyprogesterone were present. Accordingly, the patient was diagnosed as hypopituitarism due to Sheehan’s syndrome accompanied by Cushing’s syndrome as a result of an adrenocortical carcinoma. Key words: Sheehan’s syndrome, Hypopituitarism, Hypercortisolism, Adrenocortical carcinoma (Endocrine Journal 52: 219–222, 2005) SHEEHAN’S syndrome occurs as a result of ischemic with adrenocortical carcinoma may show different pituitary necrosis due to severe postpartum hemor- endocrine syndromes depending on the secretion of rhage and is characterized by various degrees of tumor; hypercortisolism and hyperandrogenism are hypopituitarism [1, 2]. Sheehan’s syndrome is a rare the most prevalent [4, 5]. postpartum complication of pregnancy with better In this report, a case with hypopituitarism due to obstetric care in developed countries. -

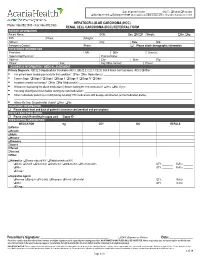

HCC/RCC Referral Form

Date Shipment Needed: Ship To: Patient Prescriber Nursing needed; Training needed ►All the supplies including syringes and needles will be dispensed if needed. HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA (HCC) Phone: 866.892.1580 • Fax: 866.892.2363 RENAL CELL CARCINOMA (RCC) REFERRAL FORM PATIENT INFORMATION Patient Name: DOB: Sex: M F Weight: lbs. kg. SSN: Phone: Allergies: Address: City: State: Zip: Emergency Contact: Phone: Please attach demographic information PRESCRIBER INFORMATION Prescriber: NPI: DEA: State Lic: Supervising Physician: Practice Name: Address: City: State: Zip: Phone: Fax: Key Office Contact: Phone: DIAGNOSIS INFORMATION / MEDICAL ASSESMENT Primary Diagnosis: C22.0 Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) C22.2; C22.7; C22.8; C64.9 Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) Other________________________________ . Has patient been treated previously for this condition? Yes No Medication(s): __________________________________________________________________ . Cancer Stage: Stage 0 Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Other: ______________________________________________________________________ . Is patient currently on therapy? Yes No Medication(s): ____________________________________________________________________________________ . Will patient stop taking the above medication(s) before starting the new medication? Yes No If yes: _________________________________________________ . How long should patient wait before starting the new medication? ________________________________________________________________________________ . Other medications patient is -

Adrenal Cortical Tumors, Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas

Modern Pathology (2011) 24, S58–S65 S58 & 2011 USCAP, Inc. All rights reserved 0893-3952/11 $32.00 Adrenal cortical tumors, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas Ricardo V Lloyd Department of Pathology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, USA Distinguishing adrenal cortical adenomas from carcinomas may be a difficult diagnostic problem. The criteria of Weiss are very useful because of their reliance on histologic features. From a practical perspective, the most useful criteria to separate adenomas from carcinomas include tumor size, presence of necrosis and mitotic activity including atypical mitoses. Adrenal cortical neoplasms in pediatric patients are more difficult to diagnose and to separate adenomas from carcinomas. The diagnosis of pediatric adrenal cortical carcinoma requires a higher tumor weight, larger tumor size and more mitoses compared with carcinomas in adults. Pheochromocytomas are chromaffin-derived tumors that develop in the adrenal gland. Paragangliomas are tumors arising from paraganglia that are distributed along the parasympathetic nerves and sympathetic chain. Positive staining for chromogranin and synaptophysin is present in the chief cells, whereas the sustentacular cells are positive for S100 protein. Hereditary conditions associated with pheochromocytomas include multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A and 2B, Von Hippel–Lindau disease and neurofibromatosis I. Hereditary paraganglioma syndromes with mutations of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD are associated with paragangliomas and some pheochromocytomas. -

ASC Webinar: Practical Approach to Liver Cytology Indication

ASC Webinar: Practical Approach to Liver Cytology Barbara A. Centeno, M.D. Director of AP Quality Assurance Director of Cytopathology and Senior member/Moffitt Cancer Center Professor/Departments of Oncologic Sciences Morsani College of Medicine University of South Florida 1 LIVER OUTLINE • Background • Cytology of benign liver and liver nodules • Cytology of Primary Liver Cancers – Hepatocellular carcinoma – Cholangiocarcinoma • Ancillary studies for key differential diagnoses • Metastases 2 Indication: Evaluation of a Mass • Nonneoplastic lesions – hemangioma • Benign liver nodule –FNH – Adenoma • Primary epithelial cancers – HCC –ICC • Less common nonepithelial neoplasms and malignancies • Metastases 3 KEY DIAGNOSTIC ISSUES • Distinction of benign or reactive hepatocytes in nonneoplastic or benign liver nodules from well- differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma • Distinction of poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma from cholangiocarcinoma or metastases • Determination of primary site of origin of metastases • Determination of histogenesis of poorly differentiated malignancie 4 APPROACH TO THE DIAGNOSIS OF LIVER LESIONS • Clinical history – Age and gender • Hepatoblastoma in infants • Adenoma in females – Underlying liver disease • HCV and Cirrhosis as a predisposing risk factor for HCC – Previous history of carcinoma • Radiological imaging – Borders, possible vascular lesion • Cytological findings • Ancillary studies • Correlate all findings 5 Hepatocytes • Monolayered sheets,thin trabeculae, single cells or small, loose groups -

Kidney Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Kidney Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis Catching cancer early often allows for more treatment options. Some early cancers may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that is not always the case. ● Can Kidney Cancer Be Found Early? ● Kidney Cancer Signs and Symptoms ● Tests for Kidney Cancer Stages and Outlook (Prognosis) After a cancer diagnosis, staging provides important information about the extent of cancer in the body and anticipated response to treatment. ● Kidney Cancer Stages ● Survival Rates for Kidney Cancer Questions to Ask About Kidney Cancer Here are some questions you can ask your cancer care team to help you better understand your cancer diagnosis and treatment options. ● Questions to Ask About Kidney Cancer 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Can Kidney Cancer Be Found Early? Many kidney cancers are found fairly early, while they are still limited to the kidney, but others are found at a more advanced stage. There are a few reasons for this: ● These cancers can sometimes grow quite large without causing any pain or other problems. ● Because the kidneys are deep inside the body, small kidney tumors cannot be seen or felt during a physical exam. ● There are no recommended screening tests for kidney cancer in people who are not at increased risk. This is because no test has been shown to lower the overall risk of dying from kidney cancer. For people at average risk of kidney cancer Some tests can find some kidney cancers early, but none of these is recommended to screen for kidney cancer in people at average risk. -

Paraneoplastic Encephalitis Associated with Renal Cell Carcinoma

Original Article pISSN 2765-4559 eISSN 2734-1461 encephalitis |Vol. 1, No. 3| May 28, 2021 https://doi.org/10.47936/encephalitis.2021.00059 Paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with renal cell carcinoma Yoonhyuk Jang, SeonDeuk Kim, Kon Chu, Sang Kun Lee, Soon-Tae Lee Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea Purpose Paraneoplastic encephalitis is autoimmune encephalitis accompanied by tumors. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a kidney cancer originating from various types of renal cells and rarely has been associated with paraneoplastic neurologic manifestation. We identified a case series of parane- oplastic encephalitis-associated RCC. Methods From a prospective institutional cohort, we identified autoimmune encephalitis patients with RCC. The association between RCC and encephali- tis was determined by the following criteria: (1) possible autoimmune encephalitis according to the operational autoimmune encephalitis diag- nostic criteria and (2) RCC simultaneously diagnosed with neurological manifestation of encephalitis. Results A total of three patients presented encephalitis accompanied by RCC. Two patients had clear cell RCC, and one had chromophobe RCC. All pa- tients showed limbic encephalitis with cognitive decline, memory impairment, or seizure. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed T2 hyperin- tensities at the mesial temporal lobe in two patients with clear cell RCC but no remarkable findings in one patient with chromophobe RCC. While one patient who had early surgery within one month of RCC onset had a favorable response to the treatment, the other two patients showed a partial response and a detrimental result. Conclusion Paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with RCC presented as limbic encephalitis and was responsive to immunotherapy combined with tumor resection.