No Classes with the Girls: Writer Evan Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

ED Mcbain M Ranso S King'

KING'S RANSOM Douglas King is rich. A nice house in the best part of the city, servants, big cars, fashionable clothes for his attractive wife, Diane. He's worked hard all his life to get where he is today, and now he's planning a big business deal. It's a very expensive deal, and there are enemies working against King, but if he wins, he'll get to be company president. If he doesn't win, he'll be out on the street. Sy Barnard and Eddie Folsom are not rich. They're small- time crooks, not very successful, but they want all the good things that money can buy. So they plan the perfect kidnapping. 'Five hundred thousand dollars by tomorrow morning, or we kill the boy,' they tell Douglas King. It's a beautiful plan. But Eddie's wife, Kathy, doesn't like it, and neither does Detective Steve Carella of the 87th Precinct. And Sy and Eddie have taken the wrong boy — not King's son, but the Reynolds boy, the son of King's chauffeur. And the chauffeur doesn't have five hundred thousand dollars. So who's going to pay the ransom? Y LIBRAR S BOOKWORM D OXFOR Mystery & Crime King's Ransom ) headwords 0 (180 5 e Stag Series Editor: Jennifer Bassett e Hedg a Trici : Editor r Founde r Baxte n Aliso d an t Basset r Jennife : Editors s Activitie ED McBAIN m Ranso s King' by novel original the from Retold Rosalie Kerr OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD CONTENTS UNIVERSITY PRESS STORY INTRODUCTION i 1 'We want your voting stock, Doug' 1 2 'Why would anyone want to steal radio parts?' 8 ' surprise! y b m hi e Tak ! attack d an n dow p 'Jum 3 12 4 'We've got your -

To Keep Your Mind Active During the Summer to Introduce You to the Rigor of Work in High School English to Give You the Opportun

English I Summer Reading Assignment Ms. Claudia Middleton Ms. Anna Russell Thornton [email protected] [email protected] Purpose & Overview HOMEWORK?! Over the SUMMER?! It’s true that doing homework during your break can be frustrating. However, it is important to do something over the summer so that we can be well prepared in the fall. Here are some reasons why we are completing this summer reading project: To give you the To introduce you to the To keep your mind active opportunity to read rigor of work in high during the summer well-known and popular school English writers To give your teacher an To preview the idea of your reading and stories that we will be writing abilities at the studying during the beginning of the school school year year For this assignment, you are required to: Step 3: Engage Step 1: Read Step 2: Annotate Choose three tasks from Pick the 5 stories you Be sure each story is the Choice Menu to will read this summer. thoroughly annotated. complete (one must be writing an OER!). Where do I get the stories? Available to you for free are all of the short stories in this packet. If you would like to print out the entire packet, feel free to do so. If you would prefer to first look through the packet online, select the stories you want to read, and ONLY print those, that is another great option. Page 1 Required Summer Reading Assignment (checklist) Access this summer reading packet online and print, if possible. -

There Is an Iconic Scene in the 1955 Film the Blackboard Jungle

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title A Transnational Tale of Teenage Terror: The Blackboard Jungle in Global Perspective Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bf4k8zq Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 6(1) Author Golub, Adam Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/T861025868 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Transnational Tale of Teenage Terror: The Blackboard Jungle in Global Perspective by Adam Golub The Blackboard Jungle remains one of Hollywood’s most iconic depictions of deviant American youth. Based on the bestselling novel by Evan Hunter, the 1955 film shocked and thrilled audiences with its story of a novice teacher and his class of juvenile delinquents in an urban vocational school. Among scholars, the motion picture has been much studied as a cultural artifact of the postwar era that opens a window onto the nation’s juvenile delinquency panic, burgeoning youth culture, and education crisis.1 What is less present in our scholarly discussion and teaching of The Blackboard Jungle is the way in which its cultural meaning was transnationally mediated in the 1950s. In the midst of the Cold War, contemporaries viewed The Blackboard Jungle not just as a sensational teenpic, but as a dangerous portrayal of U.S. public schooling and youth that, if exported, could greatly damage America’s reputation abroad. When the film did arrive in theaters across the globe, foreign critics often read this celluloid image of delinquent youth into broader -

Human Nature and Cop Art: a Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Jay Edward Baldwin University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2015 Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Jay Edward Baldwin University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Baldwin, Jay Edward, "Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1277. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1277 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural Human Nature and Cop Art: A Biocultural History of the Police Procedural A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Jay Edward Baldwin Fort Lewis College Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communication Gonzaga University Master of Arts in Communication and Leadership Studies, 2007 July 2015 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Professor Thomas Rosteck Dissertation Director Professor Frank Scheide Professor Thomas Frentz Committee Member Committee Member Abstract Prior to 1948 there was no “police procedural” genre of crime fiction. After 1948 and since, the genre, which prominently features police officers at work, has been among the more popular of all forms of literary, televisual, and cinematic fiction. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington,D.C. National Library Service for the Blind andPhysically Handicapped. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0763-1 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 172p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Audiodisks; *Audiotape Recordings; Authors; *Blindness; *Braille;Government Libraries; Large Type Materials; NonprintMedia; *Novels; *Short Stories; *TalkingBooks IDENTIFIERS *Detective Stories; Library ofCongress; *Mysteries (Literature) ABSTRACT This document is a guide to selecteddetective and mystery stories produced after thepublication of the 1982 bibliography "Mysteries." All books listedare available on cassette or in braille in the network library collectionsprovided by the National Library Service for theBlind and Physically Handicapped of the Library of Congress. In additionto this largn-print edition, the bibliography is availableon disc and braille formats. This edition contains approximately 700 titles availableon cassette and in braille, while the disc edition listsonly cassettes, and the braille edition, only braille. Books availableon flexible disk are cited at the end of the annotation of thecassette version. The bibliography is divided into 2 Prol;fic Authorssection, for authors with more than six titles listed, and OtherAuthors section, a short stories section and a section for multiple authors. Each citation containsa short summary of the plot. An order formfor the cited -

The Inventory of the Evan Hunter Collection #377

The Inventory of the Evan Hunter Collection #377 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center "'•\; RESTRICTION: Letters of ... ~. -..:::.~~- / / 12/20/67 & 1/11/68 HlJN'.J.lER, EVAN ( 112 items (mags. ) ) (167 items (short stories)) I. IV:ag-a.zines with E .H. stories ( arranged according to magazine and with dates of issues.) 11 Box 1 1. Ten Sports Stories, Hunt Collins ( pseua.~ "let the Gods Decide , '7 /52 2. Supe:c Sports, Hunt Collins (pseud.) "Fury on First" 12/51 3. Gunsmoke, "Snowblind''; 8/53 "The Killing at Triple Tree" 6/53 oi'l31 nal nllrnt:,, l1.. Famous viestej:n, S .A. Lambino ~tltt.7 11 The Little Nan' 10/52; 11 Smell the Blood of an J:!!nglishman" 5. War Stories, Hunt Collins (pseud.) 11 P-A-~~-R-O-L 11 11/52 1 ' Tempest in a Tin Can" 9/52 6. Universe, "Terwilliger and the War Ivi3,chine" 9 / 9+ 7. Fantastic J\dvantures Ted •raine (1,seud,) "Woman's World" 3/53 8. '.l'hrilling Wonder Stories, "Robert 11 ~-/53 "End as a Robot", Richard M,trsten ( pseud. ) Surrrrner /54 9, Vortex, S ,A. Lambino "Dea.le rs Choice 11 '53 .10. Cosmos, unic1entified story 9/53 "Outside in the Sand 11 11/53 11 11. If, "Welcome 1'/artians , S. A. J..Dmb ino w-1 5/ 52; unidentified story 11/ 52 "The Guinea Pigs", :3 .A. Lomb ino V,) '7 / 53; tmic1entified story ll/53 "rv,:alice in Wonderland", E.H. 1/54 -12. Imagination, "First Captive" 12/53; "The Plagiarist from Rigel IV, 3/5l1.; "The Miracle of Dan O I Shaugnessy" 12/5l~. -

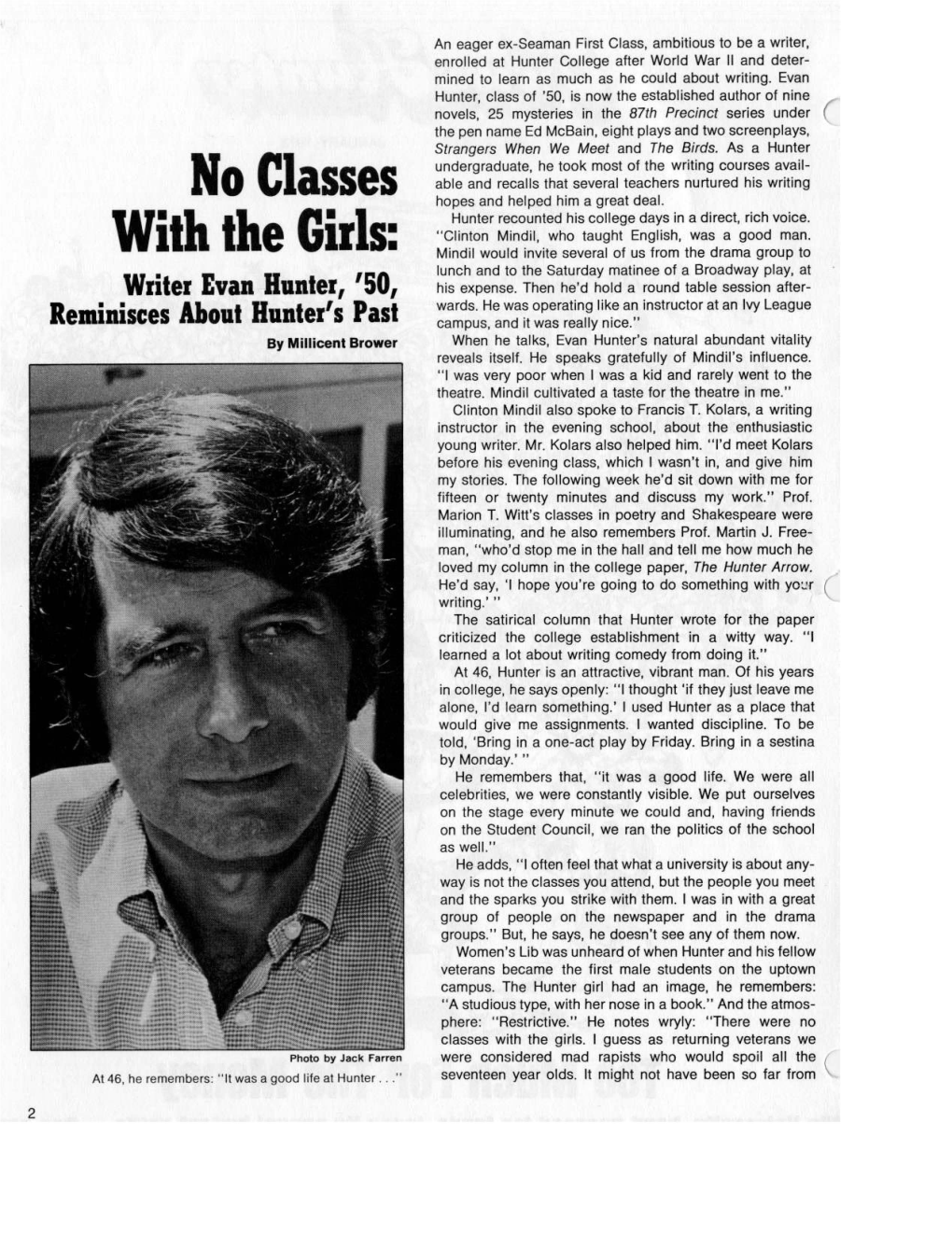

Transcript of Book Beat Radio Feature on Evan Hunter

Transcript of Book Beat radio feature on Evan Hunter Don Swaim Collection (MSS #117), Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries Broadcast circa June 26, 1984 Book Beat Reel 12, May-June 1984. Track #27 (Transcribed Track #27) swaim_broadcast_bookbeat_12_27_27.txt - With Book Beat, I'm Don Swaim. Evan Hunter is the prolific author of scores of books. His first bestseller was The Blackboard Jungle in 1954. His latest is Lizzie about the Lizzie Bordon murder case in Fall River, Massachusetts. And, writing under the name of Ed McBain, he also has a new mystery in the bookshops, Jack and the Beanstalk. Evan Hunter was born in what was then New York's Italian Harlem. At first, he wanted to be a comic strip artist. - When you're going to art school, you tend to see everything with a frame around it, you know? 'Cause that's what you're taught, to fill the rectangle, whatever it is, and to divide the space that way. And, I found that writing gave me a much larger canvas to fill. - It was in the Navy in 1944 that Hunter began to write. After his discharge, he went to Hunter College, a girls' school which had opened its doors to veterans. You might recall this scene in the movie version of The Blackboard Jungle. - Mr., uh, Dadier? - Yes, sir. - What college did you go attend? - I believe it's right there on the form, isn't it, sir? - But, that was an all-girls school. - Yes, well, they took in veterans after the war, you see. -

Twentieth- Century Crime Fiction

Twentieth-Century Crime Fiction This page intentionally left blank Twentieth- Century Crime Fiction Lee Horsley Lancaster University 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Lee Horsley The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available ISBN ––– –––– ISBN ––– –––– pbk. -

Cambridge Companion Crime Fiction

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction covers British and American crime fiction from the eighteenth century to the end of the twentieth. As well as discussing the ‘detective’ fiction of writers like Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler, it considers other kinds of fiction where crime plays a substantial part, such as the thriller and spy fiction. It also includes chapters on the treatment of crime in eighteenth-century literature, French and Victorian fiction, women and black detectives, crime in film and on TV, police fiction and postmodernist uses of the detective form. The collection, by an international team of established specialists, offers students invaluable reference material including a chronology and guides to further reading. The volume aims to ensure that its readers will be grounded in the history of crime fiction and its critical reception. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CRIME FICTION MARTIN PRIESTMAN cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521803991 © Cambridge University Press 2003 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the -

Hitchcock E Hunter. Uccelli Tra Un Grande Regista E Un Grande Scrittore

Per la critica HITCHCOCK E HUNTER. UCCELLI TRA UN GRANDE REGISTA E UN GRANDE SCRITTORE di Valerio Calzolaio Alfred Hitchcock ed Evan Hunter (alias Ed McBain) sul set del film "Gli Uccelli" Sessant’anni fa il sommo maestro del cinema Alfred Hitchcock (1899 - 1980) decise di fare un film con protagonisti migliaia di uccelli ostili ai sapiens, una sfida complicata senza tutte le tecnologie evolutesi nei decenni successivi, sfida per sceneggiatori e produttori, attori e attrici, per i tecnici e per se stesso. Il 18 agosto 1961 vi era stata un’invasione di uccelli marini “impazziti” sopra molte residenze della costa californiana, a Capitola e Santa Cruz; era successo in minor misura anche l’anno precedente; continuava a venir fuori che lì vicino corvi attaccavano agnelli e il regista si era tenuto costantemente informato sulle varie vicende. Anni prima era uscito il bel testo di Daphne du Maurier (1907 - 1989), The Birds (1953); dalla grande scrittrice inglese Hitchcock aveva già tratto ispirazione per un film del 1940 premiato con due Oscar, tra cui quello per miglior film; l’omonimo amatissimo capolavoro Rebecca, la prima moglie era stato pubblicato nel 1938. Il regista era già un personaggio mitico non solo in patria (con permanenti frequentazioni italiane, specie sul lago di Como), Psycho era stato il grande successo più recente. Dichiarò di aver letto il racconto sugli uccelli in una di quelle raccolte seriali a lui intitolate, appunto “Alfred Hitchcock racconta” e di aver saputo che tanti volevano adattarlo per la radio o la televisione, senza riuscirci. Visto che non si faceva riferimento ad avvoltoi o uccelli da preda, bensì ai tranquilli comuni uccelli di tutti i giorni, decise di provarci, cominciando a pensare ai trucchi o fotomontaggi necessari e concentrandosi sui gabbiani. -

Nova Law Review

Nova Law Review Volume 16, Issue 3 1992 Article 2 American Popular Culture’s View of the Soviet Militia: The End of the Police State? Sharon F. Carton∗ ∗ Copyright c 1992 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr American Popular Culture’s View of the Soviet Militia: The End of the Police State? Sharon F. Carton Abstract The now-defunct Soviet Union and the term “police state” have been synonymous for many years, at least from the Stalinist era until, possibly, the Gorbachev era. KEYWORDS: American, Soviet, police Carton: American Popular Culture's View of the Soviet Militia: The End of Articles American Popular Culture's View of the Soviet Militia: The End of the Police State? Sharon F. Carton* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................... 1024 II. THE ROLE OF THE POLICE IN THE SOVIET CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM .................................. 1025 A. Recent Changes in the Soviet Union ......... 1025 B. Nature and Origin of the Soviet Militia ..... 1029 C. Role of the Militia in Criminal Investigations 1031 D. Role of the Procuracy in Police Supervision .. 1035 E. Role of the KGB in the Criminal Justice System .................................. 1036 F. Police and the Criminal Code .............. 1037 III. PORTRAYAL OF SOVIET POLICE IN AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE ............................... 1039 A. Soviet Police in American Detective Fiction... 1040 1. Introduction ......................... 1040 2. The Inspector Rostnikov Series ......... 1041 a. Kaminsky's Characters........... 1041 b. The Role of Police Procedurals in Humanizing Police .............. 1048 c. Rostnikov's Police and Perestroika 1052 3. Martin Cruz Smith's Arkady Renko N ovels .............................