Wicks John.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Affairs the Nightlife of the Angelo Azzurro Sydney

N. 31 | APRIL 2021 SUPPLEMENT OF BARTALES LIQUID STORY /PETRUS HOT SPIRIT /RAICILLA BOONEKAMP, THE HOLLANDER AGAVES FOR AGUARDIENTE LIQUID STORY /DE KUYPER COCKTAIL STORY /RITUALS & MYSTERIES FAMILY AFFAIRS QUEIMADA GALLEGA ZOOM /AGAINST THE GRAIN THE NIGHTLIFE FOCUS ON /THE TEARS TOP TEN OF THE ANGELO AZZURRO SYDNEY SIDE UP BAR EDITORIAL by Melania Guida TALES EXEMPLARY STORIES uch can be attributed to lesser galangal, Alpinia officinarum, a perennial root originating from India and China. Similar to ginger and used for phar- maceutical purposes as an aromatic digestive, it brought fortune to Pieter Boonekamp, the Dutch man of the “amarissimo che fa benissimo” fame M(meaning “the very bitter [bitter] that is very good [for you]”). It was Leidschendam, 1777, when the land of tulips was one of the international crossroads of commercial shipping. Boonekamp was a skilled liqueur producer who mixed herbs and roots di- luted in spirits, until he found the recipe of a bitter that would make its way around the world. “Who does not serve (it) will die” reads (in Latin) the warning that cautions bartenders of yesteryear and today. The rest is a story of success that takes advantage of favourable commercials, like the iconic one with the fist covered in medieval armour that forcefully slams on a mahogany table, the vibrant notes of the Coriolan Overture by Ludwig Van Beethoven playing in the background. Unforgettable and legendary – just like the “Angelo Azzuro”, Mammina’s cocktail of gin, Cointreau and blue curaçao. Inspired by the cinematic masterpiece with Marlene Dietrich, the charismatic Roman barman mixed a recipe that captured the tastes and trends of the 80s and 90s. -

Voor De Nederlandse Markt Duits Steengoed Uit Het Westerwald En Van Elders 1800-1900 Adri Van Der Meulen En Ron Tousain

234 2017 / 2 Voor de Nederlandse markt Duits steengoed uit het Westerwald en van elders 1800-1900 Adri van der Meulen en Ron Tousain 3 Voorwoord 5 Inleiding 6 Westerwald Kannenbakkersland Overgang naar een nieuw asssortiment na 1750 20 Vormen en functies Nieuwe markten, nieuwe producten 36 Versiering op steengoed Naar nieuwe vormen van decoratie 58 De handel in Keulse waren Kramers, winkeliers en schippers uit het Westerwald 80 Potten met firmanamen voor handel en bedrijf De steengoed pot als verpakkingsmateriaal 130 Imitatie steengoed van de Nederlandse pottenbakkers Eigen fabricaat met weinig succces 141 Nawoord 144 Bijlagen 152 Zusammenfassung 154 English summaries Nederlandse Vereniging van Vrienden van Ceramiek en Glas vormen uit vuur I 1 Voorwoord Op 13 april 2015 is Paul Smeele in zijn woonplaats Rotterdam overleden. Hoewel hij al enige tijd ziek was met een slechte prognose kwam het einde zodanig abrupt, dat het geen gespreksonderwerp was geweest. Integendeel, hij deed tegen beter weten in zijn best om te herstellen. Maar het gevolg was dat hij geen enkele wens of instructie kenbaar had gemaakt over wat er met zijn omvangrijke nalatenschap moest gebeuren, waaronder de keramiekverzameling. Wel sprak hij soms over zijn ideeën wat betreft de voortgang van ons onderzoekswerk; hij vond dat we eens wat met de Keulse potten moesten gaan doen en ik moest daar maar vast aan beginnen. Desnoods kwam ik maar een uurtje minder op ziekenbezoek. Voor de collectie is tot nu toe geen bestemming gevonden. Gaarne zag ik dat een museum zich hierover wil ontfermen, maar dat blijkt in deze tijd geen eenvoudige zaak. -

Mix Gin Drink Jenever Rum Day Menu Distilled

Mix Day menu 11.00 to 16.00 8,— Gin & Tonic Tanqueray Tanqueray Gin, DD Cordials Tonic, rosemary and juniper berries. Hummus With Flatbread 7,50 With different kinds of hummus, olives and nuts. 9,— Gin & Tonic Vørding’s Vørding’s Gin, DD Cordials Tonic and cardamom. 3,50 Nuts 3,50 Olives 9,– Sloe Gin & Fizz Sloe (sleedoorn) Gin mixed with our wild frizzante. 6,– Homemade Chocolate Ganache Tart Gin 5,– Three Corners Premium Dry Gin, 42%, A. Van Wees 6,– Three Corners Superior Dry Gin, 42%, A. van Wees Drink 6,– Three Corners Yuzu Gin, 42%, A. van Wees 6,– Gin Vørding’s Amsterdam, Cedar wood and Orange, 44,7% Fresh Water 5,— Gin Tanqueray London, Angelica and Coriander, 43,1% 0,– With any order fresh Amsterdam tap water. Just ask. waternet.nl 5,— Sloe (sleedoorn) Gin Van der Donk, 34% Sparkling Water 2,– glass 25cl. Jenever 6,– Carafe 50cl. Apple & Pear juice 2,80 Citroenjenever, 30%/Bessenjenever, 20% A. van Wees Mappelle organic Apple+Pear juice from organic high–stem yards in 2,80 Taainagel jonge scheepsjenever, 35%, A.van Wees 3,– Werkhoven and Est. Mappelle.nl. 3,– Oude Jenever, 35%/Zeer oude Jenever, 40% A. van Wees 4,– Loyaal 5 years old jenever, 40%, A. van Wees Sparkling Lemonades Leslie and Sjoerd of Saru Soda make organic lemonades in Amsterdam Noord. dd-cordials.nl Elderflower / Sereh-Ginger / Maté-Ginseng / Cola / Iced Tea Rum 3,– Sweet or not–so–sweet? 6,– Coffee Fairtransport Ron Duro de La Palma Toradja Prince beans. Fair trade coffee imported from Indonesia 7 years aged powerful but refined rum from the Quevedo family, and roasted by Wijs en Zonen in Amsterdam. -

Bij De Borrel

Koffie (Kaffee; Coffee) 2,10 Glas licht zoete witte wijn (Wein Weiß: bißchen Süß; sweet) 3,40 Koffie verkeerd; (Milch Kaffee; Café au Lait) 2,30 Glas droge witte wijn (Wein Weiß: Trocken; White Wine: dry) 3,40 Koffie-Appelgebak (Kaffee-Apfeltorte; Coffee/Applepie) 3,75 Glas wijn Rood of Rosé (Glas Wein Rot/Rosé; Wine: Red/Rosé) 3,40 Espresso (Espresso; Espresso) 2,10 Karaf zoete of droge witte Huiswijn: halve liter 9,50 Dubbele Koffie/Espresso (Espresso; Espresso) 2,95 Karaf Rood of Rosé Huiswijn: halve liter 9,50 Cappuccino (Cappuccino; Cappuccino) 2,30 Advocaat (Glas Eier Likör; Glass of Eggnog ) 50 cc. 1,90 Cappuccino Speciaal: incl. glaasje advocaat met slagroom 3,95 Advocaat met slagroom (Glas Eier Likör mit Sahne; Glass of Eggnog with Whipped Cream) 50 cc. 2,65 Ierse Koffie: met Whisky (Kaffee mit Whisky; Coffee with Whisky) 5,45 Franse Koffie: met Grand Marnier (mit Grand Marnier; with Grand Marnier) 5,95 Amaretto (Glas Amaretto; Glass of Amaretto) 35 cc. 2,85 Calypso Koffie: met Tia Maria (mit Tia Maria; with Tia Maria) 5,35 Bacardi Witte Rum (Weiße Rum; White Rum) 35 cc 2,95 Schotse Koffie: met Drambuie (mit Drambuie; with Drambuie) 5,95 Pisang Ambon (Pisang Ambon; Pisang Ambon) 35 cc. 2,45 Warme Chocolademelk (Warmer Kakao; Hot Chocolate) 2,20 Grand Marnier (Glas Grand Marnier; glass of Grand Marnier) 35 cc. 4,25 Warme Chocolademelk met Slagroom (Warmer Kakao mit Sahne; Gin (Glas Gin; glass of English Gin) 35 cc. 3,85 Hot Chocolate with Whipped Cream) 2,85 Drambuie (Glas Drambuie; glass of Drambuie) 35 cc. -

Intoxication and Empire: Distilled Spirits and The

INTOXICATION AND EMPIRE: DISTILLED SPIRITS AND THE CREATION OF ADDICTION IN THE EARLY MODERN BRITISH ATLANTIC by KRISTEN D. BURTON Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2015 Copyright © by Kristen D. Burton 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Many describe writing a dissertation as an isolating task, and yet, so many people make the creation of this work possible. Guidance from my committee helped me as I shifted through an array of ideas and resources. My mentor, Christopher Morris, provided essential assistance as I wrangled what was once a bewildered narrative. Elisabeth Cawthon, John Garrigus, and Sarah F. Rose also helped me pull together, first, cohesive chapters, then an organized manuscript. Insightful conversations with Frederick H. Smith were remarkably helpful. I also owe him my thanks for offering his time as an outside reader. Fellowships from the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington supported a large portion of my research. My deepest thanks to Conrad E. Wright, Daniel Hinchen, Sarah Georgini, Sarah K. Myers, Mark Santangelo, Neal Millikan, Michele Lee, and Mary V. Thompson for all your help in guiding my research. I owe thanks also to Douglas Bradburn for his mentorship during my stay at Mount Vernon. Finally, to my colleagues, family, and friends, your enduring support helped me to see this to the end. My parents, and my dear husband, Daniel, never wavered in their support. -

1Dr 30-3 De Wijn & Whisky Schuur.Xlsx

De Wijn & Whisky Schuur Drankenassortiment inh artikel soort Berenburg 1,00Bijlsma Beerenburg 1,00Boomsma Berenburg 1,00 Brons Berenburg 1,00Glaasje Berenburg 1,00Hooghoudt Kalmoes Beerenburg 1,00Hooghoudt 74 kruiden Beerenburg 1,00Joustra 32% Beerenburg 0,50Joustra 32% Beerenburg 1,00Joustra 35% Beerenburg 0,50Joustra Sjirurg 40% Beerenburg 0,70 Joustra FS 3 Jr Beerenburg 0,70Joustra FSOB 5 Jr Beerenburg 1,00 Meyers & Oldenkamp Berenburg 0,50 Meyers & Oldenkamp Berenburg 1,00Schermer Beerenburg 1,50Sonnema Berenburg 1,00Sonnema Berenburg 0,50Sonnema Berenburg 1,00 Stiekeme Stoker Fryske Bearenburch Kruidenbitters Nederland 0,70 Beerinneburg Kruidenbitter 1,00 Bijlsma Jachtbitter Kruidenbitter 0,70 Claerkampster Kruidenbitter 0,70 Fireman Kruidenbitter 0,70Gorter Jachtbitter Kruidenbitter 1,00 Hooghoudt Zachtbitter Kruidenbitter 0,70 Juttertje Kruidenbitter 1,00 Nobeltje Rumpunch/bitter 0,70 Sarah Schermer 1,00 Scheepsborrel Rumbitter 1,00 Schipperbitter Kruidenbitter 0,70 Schylgebitter Kruidenbitter 1,00 Snitserbitter Kruidenbitter 0,70 Snitserbitter Kruidenbitter 0,35 Snitserbitter Kruidenbitter Kruidenbitters Buitenland 0,20 Angostora Dr.Siegert Kruidenbitter 1,00 Aperol Kruidenbitter 0,70 Averna Amaro Kruidenbitter 1,00 Becherovka Kruidenbitter 1,00 Campari Kruidenbitter 0,70 Campari Kruidenbitter 0,70 Fernet Branca Kruidenbitter 0,70 Gammeldansk Kruidenbitter 1,00 Jägermeister Kruidenbitter 0,70 Jägermeister Kruidenbitter 0,70 Killepitch Kruidenbitter 0,70 Pimm's Kruidenbitter 0,70 Ramazotti Amaro Kruidenbitter 0,70 Cynar Kruidenbitter -

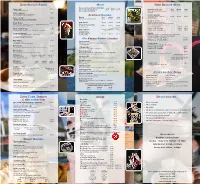

Download the Complete Menu Here As a PDF File

Dutch Starters/Snacks Mains Other Delicious Mains Bacon or Ham and Eggs (Uitsmijter) Small Medium Large Patat ,,Met” $7.00 Pan-fried eggs, with grilled bacon or $9.90 $14.90 $16.90 Vegetarian pancake Small Medium Large Fries with Dutch mayonnaise ham, cheese & served with toast With a variety of stir-fried vegetables $17.90 $19.90 $21.90 Patat ,,Speciaal” $7.50 and cheese Fries with tomato or Dutch curry Ketchup, Dutch mayonnaise and fresh diced onion Traditional Pancakes Diabetic pancake Served with a variety of fresh fruit $14.90 $16.90 $18.90 Natural Small Medium Large Patat ,,Oorlog” $7.50 and diabetic jam Fries with Dutch mayonnaise & Dutch Delight’s With icing sugar and lemon wedges $8.00 $11.90 $14.50 homemade peanut sauce and fresh diced onion Satays on a stick Spek (Bacon) $12.50 $14.50 $17.50 Delightful Chicken or Pork satay Dutch Kroket $4.90 grilled, marinated home-style chicken or pork meat With seared apple or pineapple A Dutch croquette, goulash, beef, chicken or vegetarian with mustard with Dutch Delight's homemade peanut sauce or banana or onion & mushrooms $14.90 $16.90 $20.90 Also available on a bun for $1.00 extra served with fries and salad or onion & tomato Chicken Pork Nassi or Bami Schijf $6.50 Mother's size (3 sticks) $22.50 $24.50 Crumbed Fried rice or Noodle snack, also available as vegetarian Ham & Cheese $12.50 $14.50 $17.50 Father's size (4 sticks) $25.50 $27.50 With seared apple or pineapple or banana Fricandel Speciaal $6.50 or onion & mushrooms $14.90 $16.90 $20.90 Shaslick A Dutch sausage with tomato -

7-3577 Food Lovers a 6/19/07 3:34 PM Page 1

7-3577_Food Lovers A 6/19/07 3:34 PM Page 1 1 A balone [a-buh-LOH-nee] A GASTROPOD MOLLUSK (see both listings) found along the coastlines of California, Mexico and Japan. The edible portion is the adductor muscle, a A broad foot by which the abalone clings to rocks. As with any muscle, the meat is tough and must be pounded to ten- derize it before cooking. Abalone, used widely in Chinese and Japanese cooking, can be purchased fresh, canned, dried or salted. Fresh abalone should smell sweet, not fishy. It should also be alive—the exposed muscle should move when touched. Choose those that are rel- atively small and refrigerate as soon as possible. Cook abalone within a day of purchase. Fresh abalone is best sautéed and should be cooked very briefly (20 to 30 seconds per side) or the meat will quickly toughen. Abalone is known as ormer in the English Channel, awabi in Japan, muttonfish in Australia and paua in New Zealand. Its iridescent shell is a source of mother-of-pearl. See also SHELLFISH. abbacchio [ah-BAHK-ee-yoh] Italian for a very young lamb. Abbaye de Belloc (Bellocq) [ah-bay-EE deuh behl-LAWK] Semihard sheep’s-milk cheese that’s been made for centuries by the Benedictine monks at the Abbey de Belloc in the Pays Basque area of southwestern France. The cheese is traditionally made with milk from Manech sheep, though milk from other breeds may be used. It comes in 8- to 11-pound wheels with a hard brownish rind and a pale ivory inte- rior. -

Alcohol and Heart Disease 1

The Correlation between Drinking Alcohol and Heart Diseases of Men in the age of 20 - 35 years old in Puri Indah, West Jakarta in 2006. Name: Robby Effendy Thio NIM: 030.06.228 English Lecturer: Drs. Husni Thamrin, MA Chapter I Introduction Any advice about the consumption of alcohol must take into account not only the complex relation between alcohol and cardiovascular disease but also the well-known association of heavy consumption of alcohol with a large number of health risks. One approach would be to recommend no consumption of alcohol. However, a large number of recent observational studies have consistently demonstrated a reduction in coronary heart disease (CHD) with moderate consumption of alcohol. Any prohibition of alcohol would then deny such persons a potentially sizable health benefit. This paper examines the complex relation between alcohol and coronary heart disease. I. Background I examined the association between alcoholic drinks consumption and risk of heart diseases such as: Coronary Heart Disease (CHD). II. Problems Drinking Alcohols have always been related to heart diseases especially for Men in the age of 20 - 35 years old in Puri Indah, West Jakarta. III. Limitation of Problems The Limitation of this problem is the lifestyle of young men (between the age of 20 – 35) that is drinking alcohols and what are the effects of drinking alcohols in relation to heart diseases. IV. Objectives The main objective is to show up what are the effects of alcohol consumption to heart diseases, in medicals point of view. V. Methods of Writing Library Research and Internet Browsing (Collecting Information). -

BANQUETINGBOOK 2015 Vondelpark3 1

BANQUETINGBOOK 2015 VONDELPARK3 1. YOUR EVENT SUPPORTS MEALFORMEAL Vondelpark3 would like to introduce you to MealforMeal, a new sustainable initiative created by ourselves. MealforMeal wants to create a better future for people in need of food, people that might live next to you. Cooperation with Voedselbanken Nederland Along with Voedselbanken Nederland, MealforMeal committed to deprive people of a daily concern: the concern of having enough to eat and drink. By providing food parcels to people in need we not only fight poverty, we also reduce food waste and the impact on the environment. Although Voedselbanken Nederland never pays for food, financial support is more than welcome. The storage of food and the weekly distribution to 146 sites is very expensive. With the money MealforMeal collects, we support this logistics process and improve it where necessary. Simply put, you will contribute to the delivery of food to those in need, while you deliver an unforgettable event to your guests! What is your contribution? All prices for food and beverages listed in the banqueting book of Vondelpark3 include a contribution. All together, every guest of your event contributes one euro to MealforMeal. One euro that is directly reinvested in the logistics of Voedselbanken Nederland. On behalf of MealforMeal we thank you for this contribution! All prices shown are exclusive VAT 2. RENTAL PRICES HALLS & TERRACES Nr. Name hall Floor Size Price per daily period 1 Studio B 1st floor 114m2 €780,- 2 Studio A 1st floor 112,5m2 €780,- 3 Media Bar 1st floor 86m2 Can’t be rented individually 4 French Room 1st floor 61m2 €530,- 5 Media Café 1st floor 61m2 €280,- 6 Meeting Atelier Top floor 50m2 €280,- 7 Terrace A 1st floor 100m2 €700,- 8 Terrace B 1st floor 100m2 €700,- Rental prices are per daily period. -

Broccoli, Pear, Kale, Kiwi, Banana 4.60 Glass / Bottle Heineken Extra Cold 50 Cl

Draught Beers Savse smoothies WINELIST Heineken 25 cl. 3.00 Cold pressed veg and fruit, super healthy, raw, For reasons of sustainability and quality, we serve European Heineken Extra Cold 3.20 unpasteurized, delicious! wines Heineken 50 cl. 5.60 Cleansing: broccoli, pear, kale, kiwi, banana 4.60 glass / bottle Heineken Extra Cold 50 cl. 5.90 Antioxidant: beetroot, apple, avocado, lime, mango 4.60 Open white Pitcher Heineken 1,5 l 15.50 Monterre Viognier (France) 4.00 / 19.00 Brand Weizen 4.20 Soft drinks Monterre Sauvignon Blanc (France) 4.20 / 19.50 Affligem Dubbel 4.20 Crystal Clear sparkling lemon 2.80 Brand I.P.A. 4.20 Sourcy mineral water 2.80 Nebla Rueda, Verdejo (Spain) 4.50 / 22.50 Seasonal specials 4.20 Sourcy 75 cl. 5.50 Pasqua, Pinot Grigio (Italy) 5.00 / 25.00 7UP 2.80 Bottled beers & ciders Pepsi regular / light 2.80 Open red Wieckse Rosé 4.50 SiSi fizzy orange 2.80 Duvel 5.00 Rivella light 2.80 Monterre Merlot (France) 4.00 / 19.00 Judas 5.00 Royal Club Bitter Lemon 2.80 Pasqua Montepulciano d’Abruzzo 4.50 / 22.50 Sol 5.00 Royal Club Tonic 2.80 Montepulciano (Italy) Affligem blond 5.00 Royal Club Ginger Ale 2.80 Nebla Ribera del Duero 5.00 / 25.00 Affligem triple 5.00 Royal Club Soda Water 2.80 Tempranillo (Spain) Brand Zwaar Blond (strong) 5.00 Royal Club Cassis 2.80 Locally Brewed Triple (IJ-beer “Zatte”) 5.00 Liptonice icetea / green tea 2.80 Open rosé La Chouffe 5.00 Thomas Henry tonic water 3.50 Amstel Radler lemon beer 2% 3.50 Thomas Henry elderflower tonic 3.50 Domaine de Medeilhan 4.00 / 19.00 Ciders, see our cider menu from 4.00 Thomas Henry ginger beer 3.50 Syrah, Cinsault (France) Alcohol free Amstel 0.0 3.50 Thomas Henry ginger ale 3.50 Alcohol free white beer 0.0 3.50 Bottle white Spirits Weingut Allram Strassertaler, 28.50 Hot drinks Bols jonge jenever (Dutch gin) 3.80 Grüner Veltliner (Austria) Senza: lovely tealeafs, many varieties 2.60 Bols oude jenever (matured) 3.80 Fresh mint tea 2.90 Bols Vieux (Dutch brandy) 3.80 Laroche, Chablis St. -

A Study of the Evolution of Concentration in the Dutch Beverages Industry

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE DUTCH BEVERAGES INDUSTRY November 1976 In 1970 the Commission initiated a research programme on the evolution of concentration and competition in several sectors and markets of manufacturing industries in the different Member States (textile, paper, pharmaceutical and photographic products, cycles and motorcycles, agricultural machinery, office machinery, textile machinery, civil engineering equipment, hoist· ing and handling equipment, electronic and audio equipment, radio and television receivers, domestic electrical appliances, food and drink manufacturing industries). The aims, criteria and principal results of this research are set out in the document "Methodolo gie de !'analyse de Ia concentration appliquee a !'etude des secteurs et des marches", (ref. 8756- french version), September 1976. This particular volume presents the results of the research on the beverages industry in the Netherlands, while similar volumes concerning this industry are also being published for other Member States (France, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Belgium and Denmark). COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE DUTCH BEVERAGES INDUSTRY Manuscript finished in November 1976 © Copyright ECSC/EEC/EAEC, Brussels, 1976 Printed in Belgium Reproduction authorized, in whole or in part, provided the source is acknowledged PREFACE The present volume is part of a series of sectoral studies on the evolution of concentration in the member states of the European Community. These reports were compiled by the different national Institutes and experts, engaged by the Commission to effect the study programme in question. Regarding the specific and general interest of these reports and the responsibility taken by the Commission with regard to the European Parliament, they are published wholly in the original version.