Traces of Buddhism in Sumatra: an Archaeological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” E‐Book

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Padmakumara website would like to gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for contributing to the production of “Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” e‐book. Translator: Alice Yang, Zhiwei Editor: Jason Yu Proofreader: Renée Cordsen, Jackie Ho E‐book Designer: Alice Yang, Ernest Fung The Padmakumara website is most grateful to Living Buddha Lian‐sheng for transmitting such precious dharma. May Living Buddha Lian‐sheng always be healthy and continue to teach and liberate beings in samsara. May all sentient beings quickly attain Buddhahood. Om Guru Lian‐Sheng Siddhi Hum. Exhaustive research was undertaken to ensure the content in this e‐book is accurate, current and comprehensive at publication time. However, due to differing individual interpreting skills and language differences among translators and editors, we cannot be responsible for any minor wording discrepancies or inaccuracies. In addition, we cannot be responsible for any damage or loss which may result from the use of the information in this e‐book. The information given in this e‐book is not intended to act as a substitute for the actual lineage and transmission empowerments from H.H. Living Buddha Lian‐sheng or any authorized True Buddha School master. If you wish to contact the author or would like more information about the True Buddha School, please write to the author in care of True Buddha Quarter. The author appreciates hearing from you and learning of your enjoyment of this e‐book and how it has helped you. We cannot guarantee that every letter written to the author can be answered, but all will be forwarded. -

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Mythology and the Belief System of Sunda Wiwitan: a Theological Review in Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency of West Java, Indonesia

International Journal of Research and Review Vol.7; Issue: 4; April 2020 Website: www.ijrrjournal.com Research Paper E-ISSN: 2349-9788; P-ISSN: 2454-2237 Mythology and the Belief System of Sunda Wiwitan: A Theological Review in Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency of West Java, Indonesia Tita Rostitawati Department of Philosophy, State Islamic University of Sultan Amai Gorontalo, Indonesia ABSTRACT beliefs that are based on ideas in the teachings of ancestors or spirits. There are This study examined the mythology and belief several villages in West Java, which are systems adopted by the Sunda Wiwitan manifestations of the existence of community that were factually related to the indigenous peoples in Indonesia. credo system that was considered sacred in a The existence of traditional villages belief. Researcher in collecting data using interviews, observation, and literature review is a special attraction for the community methods. The process of data analysis was done because there is a unique culture and is with qualitative data analysis techniques. In the different from the others, such as the process of analyzing research data, the Sundanese people in the Cisolok village of researcher organized data, grouped data, and Sukabumi Regency. Human life requires a analyzed narratively. The results showed that belief in which the belief is in the form of the Sunda Wiwitan belief system worshiped religious teachings or views that, according ancestral spirits as an elevated entity. Aside to the community, are considered good and from worshiping ancestors, Sunda Wiwitan also true. In Cisolok of Sukabumi Regency, there had a God who was often called Sang Hyang are cultural and traditional elements that are Kersa. -

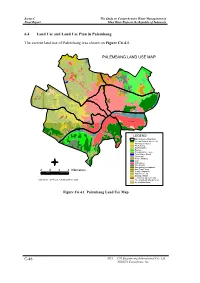

C-46 6.4 Land Use and Land Use Plan in Palembang the Current Land Use of Palembang Was Shown on Figure C6.4.1

Sector C The Study on Comprehensive Water Management of Final Report Musi River Basin in the Republic of Indonesia 6.4 Land Use and Land Use Plan in Palembang The current land use of Palembang was shown on Figure C6.4.1. PALEMBANG LAND USE MAP sa k o suk a r a me Ilir Barat I Ilir Timur I Ilir Tim ur II Seberang Ulu II Ilir Barat II LEGEND Administrative Boundary 1x Tidal Swamp Rice Field Agriculture Industy Seberang Ulu I Big Building Big Plantation Bushes Dry Agriculture Land Fresh Water Pond Graveyard N House Building Lak e Li vi ng Area Mi xed Land Non-agriculture Industry One Type Forest 2024Kilometers People Plantation Rain Rice Field Swamp / Marsh Temporary Opened Land Data Source : BAPPEDA 1:50,000 Land Use 2000 Tree and Bush Mixed Forest Un-identified Land Figure C6.4.1 Palembang Land Use Map C-46 JICA CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. The Study on Comprehensive Water Management of Sector C Musi River Basin in the Republic of Indonesia Final Report In 1994, Palembang Municipality made the first spatial plan that the target years are from 1994 to 2004. 5 years late in 1998, this spatial plan was reviewed and evaluated by PT Cakra Graha through a contract project with Regional Development Bureau of Palembang Municipality (Contract No. 602/1664/BPP/1998). After the evaluation and analysis, a new spatial plan 1999 to 2009 was designed, however, the data used in the new spatial plan was the same as the one in the old plan 1994 to 2004. -

Journal Für Religionskultur

________________________________ Journal of Religious Culture Journal für Religionskultur Ed. by / Hrsg. von Edmund Weber in Association with / in Zusammenarbeit mit Matthias Benad, Mustafa Cimsit, Natalia Diefenbach, Alexandra Landmann, Martin Mittwede, Vladislav Serikov, Ajit S. Sikand , Ida Bagus Putu Suamba & Roger Töpelmann Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main in Cooperation with the Institute for Religious Peace Research / in Kooperation mit dem Institut für Wissenschaftliche Irenik ISSN 1434-5935 - © E.Weber – E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/irenik/religionskultur.htm; http://irenik.org/publikationen/jrc; http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/solrsearch/index/search/searchtype/series/id/16137; http://web.uni-frankfurt.de/irenik/ew.htm; http://irenik.org/ ________________________________ No. 215 (2016) Dang Hyang Astapaka and His Cultural Geography in Spreading Vajrayana Buddhism in Medieval Bali1 By Ida Bagus Putu Suamba2 Abstract The sway of Hinduism and Buddhism in Indonesia archipelago had imprinted deep cultural heritages in various modes. The role of holy persons and kings were obvious in the spread of these religious and philosophical traditions. Dang Hyang Asatapaka, a Buddhist priest from East Java had travelled to Bali in spreading Vajrayana sect of Mahayana Buddhist in 1430. He came to Bali as the ruler of Bali invited him to officiate Homa Yajna together with his uncle 1 The abstract of it is included in the Abstact of Papers presented in the 7th International Buddhist Research Seminar, organized by the Buddhist Research Institute of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Ayutthaya, Thailand held from the 18th to the 20th of January, 2016 (2559 BE) at Mahachulalongkornrajavidy- alaya University, Nan Sangha College, Nan province. -

BAB II LANDASAN TEORI 2.1 Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta

BAB II LANDASAN TEORI 2.1 Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (DIY) merupakan Provinsi terkecil kedua setelah Provinsi DKI Jakarta dan terletak di tengah pulau Jawa, dikelilingi oleh Provinsi Jawa tengah dan termasuk zone tengah bagian selatan dari formasi geologi pulau Jawa. Di sebelah selatan terdapat garis pantai sepanjang 110 km berbatasan dengan samudra Indonesia, di sebelah utara menjulang tinggi gunung berapi paling aktif di dunia merapi (2.968 m). Luas keseluruhan Provinsi DIY adalah 3.185,8 km dan kurang dari 0,5 % luas daratan Indonesia. Di sebelah barat Yogyakarta mengalir Sungai Progo, yang berawal dari Jawa tengah, dan sungai opak di sebelah timur yang bersumber di puncak Gunung Merapi, yang bermuara di laut Jawa sebelah selatan. (Kementerian RI, 2015) Yogyakarta merupakan salah satu daerah yang memiliki kebudayaan yang masih kuat di Indonesia, dan juga Yogyakarta memiliki banyak tempat-tempat yang bernilai sejarah salah satunya situs-situs arkeologi, salah satu dari situs arkeologi yang banyak diminati untuk dikunjungi para masyarakat dan wisatawan adalah peninggalan situs-situs candi yang begitu banyak tersebar di Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta. 2.2 Teori Dasar 2.2.1 Arkeologi Kata arkeologi berasal dari bahasa yunani yaitu archaeo yang berarti “kuna” dan logos “ilmu”. Definisi arkeologi adalah ilmu yang mempelajari kebudayaan (manusia) masa lalau melalui kajian sistematis (penemuan, dokumentasi, analisis, dan interpretasi data berupa artepak contohnya budaya bendawi, kapak dan bangunan candi) atas data bendawi yang ditinggalkan, yang meliputi arsitektur, seni. Secara umum arkeologi adalah ilmu yang mempelajari manusia beserta kebudayaan-kebudayaan yang terjadi dimasa lalu atau masa lampau melalui peninggalanya. Secara khusus arkeologi adalah ilmu yang mempelajari budaya masa silam yang sudah berusia tua baik pada masa prasejarah (sebelum dikenal tulisan) maupun pada masa sejarah (setelah adanya bukti-bukti tertulis). -

Challenges in Conserving Bahal Temples of Sri-Wijaya Kingdom, In

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-9, Issue-1, October 2019 Challenges in Conserving Bahal Temples of Sriwijaya Kingdom, in North Sumatra Ari Siswanto, Farida, Ardiansyah, Kristantina Indriastuti Although it has been restored, not all of the temples re- Abstract: The archaeological sites of the Sriwijaya temple in turned to a complete building form because when temples Sumatra is an important part of a long histories of Indonesian were found many were in a state of severe damage. civilization.This article examines the conservation of the Bahal The three brick temple complexes have been enjoyed by temples as cultural heritage buildings that still maintains the authenticity of the form as a sacred building and can be used as a tourists who visit and even tourists can reach the room in the tourism object. The temples are made of bricks which are very body of the temple. The condition of brick temples that are vulnerable to the weather, open environment and visitors so that open in nature raises a number of problems including bricks they can be a threat to the architecture and structure of the tem- becoming worn out quickly, damaged and overgrown with ples. Intervention is still possible if it is related to the structure mold (A. Siswanto, Farida, Ardiansyah, 2017; Mulyati, and material conditions of the temples which have been alarming 2012). The construction of the temple's head or roof appears and predicted to cause damage and durability of the temple. This study used a case study method covering Bahal I, II and III tem- to have cracked the structure because the brick structure ples, all of which are located in North Padang Lawas Regency, does not function as a supporting structure as much as pos- North Sumatra Province through observation, measurement, sible. -

Hak Cipta Dan Penggunaan Kembali: Lisensi Ini Mengizinkan Setiap

Hak cipta dan penggunaan kembali: Lisensi ini mengizinkan setiap orang untuk menggubah, memperbaiki, dan membuat ciptaan turunan bukan untuk kepentingan komersial, selama anda mencantumkan nama penulis dan melisensikan ciptaan turunan dengan syarat yang serupa dengan ciptaan asli. Copyright and reuse: This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon work non-commercially, as long as you credit the origin creator and license it on your new creations under the identical terms. Team project ©2017 Dony Pratidana S. Hum | Bima Agus Setyawan S. IIP BAB II TINJAUAN PUSTAKA 2.1. Animasi Animasi berasal dari bahasa latin animare yang berarti „to give life to’. Jadi animator ingin menekankan bahwa membuat animasi itu bearti memberikan nyawa dan jiwa kepada sebuah desain, bukan hanya mengkopi gambar (Wells, 1998). Sebelum masehi manusia membuat gambar pada objek sehari-hari yang digambar secara berlanjut, seperti gambar bison yang memiliki banyak kaki seakan-akan kakinya bergerak, menunjukan keinginan manusia menggerakan sebuah gambar. Sampai abad 18 ditemukannya alat-alat ilusi gerak cikal-bakal pembuatan animasi yang menggunakan kertas yang di-flip (Williams, 2001). Jadi animator membuat gambar frame by frame lalu seiring perkembangan jaman animasi menggunakan alat digital yang memudahkan proses pengerjaan. Salah satunya berkembangnya animasi 3D dimana proses pengerjaannya hampir menggunakan komputer. Biasanya animasi 3D digunakan untuk dunia hiburan, keilmuan, dan lainnya. 4 Perancangan Karakter...,Gracia Novita,FSD UMN,2017 2.1.1. Proses Pembuatan Animasi 3D Secara umum membuat sebuah film animasi panjang atau pendek memiliki garis besar yang sama yaitu; pre-production, production, dan post-production. Gambar 2.1.Pipeline Animasi 3D (http://www.upcomingvfxmovies.com/wp- content/uploads/2014/03/3d_production_timelines.jpeg) Langkah pertama membuat sebuah film yaitu membuat pre- production. -

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Kerajaan Koto Besar

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Kerajaan Koto Besar diperkirakan telah ada sejak akhir abad ke-17 Masehi.1 Koto Besar tumbuh dan berkembang bersama daerah-daerah lain yang berada di bekas wilayah Kerajaan Melayu Dharmasraya (Swarnabumhi).2 Daerah-daerah ini merupakan kerajaan kecil yang bercorak Islam dan berafiliasi dengan Kerajaan Pagaruyung, seperti Pulau Punjung yang dikenal sebagai camin taruih (perpanjangan tangan) Pagaruyung untuk daerah Hiliran Batanghari, serta penguasa lokal di ranah cati nan tigo, yaitu Siguntur, Sitiung dan Padang Laweh.3 Koto Besar menjadi satu-satunya kerajaan di wilayah ini yang tidak berpusat di pinggiran Sungai Batanghari.4 Lokasi berdirinya kerajaan-kerajaan tersebut merupakan daerah rantau dalam konsep alam Minangkabau.5 Pepatah adat Minangkabau mengatakan, 1 Merujuk pada tulisan yang tercantum pada stempel peninggalan Kerajaan Koto Besar yang berangkakan tahun 1697 Masehi. 2 Kerajaan Melayu Dharmasraya (Swarnabumhi) adalah sebuah kerajaan yang bercorak Hindu Buddha dan merupakan kelanjutan dari Kerajaan Melayu Jambi yang bermigrasi dari muara Sungai Batanghari. Kerajaan Melayu Dharmasraya hanya bertahan sekitar dua abad (1183 – 1347), setelah dipindahkan oleh Raja Adityawarman ke pedalaman Minangkabau di Saruaso. Bambang Budi Utomo dan Budhi Istiawan, Menguak Tabir Dharmasraya, (Batusangkar : BPPP Sumatera Barat, 2011), hlm. 8-12. 3 Efrianto dan Ajisman, Sejarah Kerajaan-Kerajaan di Dharmasraya, (Padang: BPSNT Press, 2010), hlm. 84. 4 Menurut Tambo Kerajaan Koto Besar dijelaskan bahwa Kerajaan Koto Besar berpusat di tepi Sungai Baye. Hal ini juga dikuatkan oleh catatan Kontroler Belanda Palmer van den Broek tanggal 15 Juni 1905. Lihat, Tambo Kerajaan Koto Besar, “Sejarah Anak Nagari Koto Besar yang Datang dari Pagaruyung Minangkabau”. Lihat juga, “Nota over Kota Basar en Onderhoorige Landschappen Met Uitzondering van Soengei Koenit en Talao”, dalam Tijdschrift voor Indische, “Taal, Land en Volkenkunde”, (Batavia: Kerjasama Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen dan Batavia Albrecht & Co., 1907), hlm. -

Y3216 Lloyd's Agencies in Indonesia, Kota Kinabalu, Sandakan, Cayenne

Market Bulletin One Lime Street London EC3M 7HA FROM: Sonja Fink, Controller of Agencies Agency Department LOCATION: 86/Room 209 EXTENSION: 5735 DATE: 17 December 2003 REFERENCE: Y3216 SUBJECT: LLOYD’S AGENCIES IN INDONESIA, KOTA KINABALU, SANDAKAN, CAYENNE, PARAMARIBO, RECIFE, RIO DE JANEIRO, RIO GRANDE, SANTOS, HALMSTAD, GOTHENBURG, KARLSHAMN AND MALMO. SUBJECT AREA(S): None ATTACHMENTS: None ACTION POINTS: None DEADLINE: None LLOYD’S AGENCIES AT JAKARTA, MAKASSAR, MEDAN, PALEMBANG, SEMARANG AND SURABAYA. Please note that P.T.Superintending Company of Indonesia’s Lloyd’s Agency appointments at Makassar, Medan, Palembang, Semarang and Surabaya will terminate at the end of this year and that with effect from 1 January, 2004, PT Carsurin will be the appointed Lloyd’s Agents for Indonesia. Their full contact details are as follows: P.T.Carsurin Pekaka Building 7th Floor Jl. Angkasa Blok B-9 Kav 6 Kota Baru Bandar Kamayoran Jakarta 10720 Indonesia Contact : Captain Irawan Alwi or Captain Sunardi Setiaharja Telephone : +62 21 6540425 or 6540393 or 6540417 Facsimile : +62 21 6540418 Mobile : +62 811 103513 – Capt. Setiaharja Email : [email protected] Website : www.carsurin.com Lloyd’s is regulated by the Financial Services Authority 2 LLOYD’S AGENCIES AT KOTA KINABALU AND SANDAKAN. Harrisons Trading (Sabah) Sdn., Bhd., the Lloyd’s Agents at Kota Kinabalu and Sandakan have decided to amalgamate their existing two offices which will, with effect from 1st January 2004 be administered from Kota Kinabalu. As a result the Lloyd’s Agency at Sandakan is now a Sub-Agent of Kota Kinabalu, and its territory has been added to that of the Lloyd’s Agency at Kota Kinabalu, whose full contact details are as follows: Harrisons Trading (Sabah) Sdn., Bhd., 19 Jalan Haji Saman.