Prints and Drawings by and After Such Masters As Raphael, Titian Fig 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Knox Giles Knox Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt of Italian Renaissance Art Challenge the Knowledge Sense and FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the Nation- al Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Wom- en, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt Giles Knox Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS This book was published with support from the Office of the Vice Provost for Research, Indiana University, and the Department of Art History, Indiana University. -

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638)

CORNELIS CORNELISZ. VAN HAARLEM (1562 – Haarlem – 1638) _____________ The Last Supper Signed with monogram and dated 1636, lower centre On panel – 14¾ x 17⅜ ins (37.4 x 44.2 cm) Provenance: Private collection, United Kingdom since the early twentieth century VP 3691 The Last Supperi which Christ took with the disciples in Jerusalem before his arrest has been a popular theme in Christian art from the time of Leonardo. Cornelis van Haarlem sets the scene in a darkened room, lit only by candlelight. Christ is seated, with outstretched arms, at the centre of a long table, surrounded by the twelve apostles. The artist depicts the moment following Christ’s prediction that one among the assembled company will betray him. The drama focuses upon the reactions of the disciples, as they turn to one another, with gestures of surprise and disbelief. John can be identified as the apostle sitting in front of Christ who, as the gospel relates, ‘leaned back close to Jesus and asked, “Lord, who is it?”ii and Andrew, an old man with a forked beard, can be seen at the right-hand end of the table. Only Judas, recognisable by the purse of money he holds in his right handiii, turns away from the table and casts a shifty glance towards the viewer. The bread rolls on the table and the wine flagon held by the apostle on the right make reference to the sacrament of the eucharist. This previously unrecorded painting, dating from 1636, is a late work by Cornelis van Haarlem and is characteristic of the moderate classicism which informed his work from around 1600 onwards. -

Rembrandt: a Milestone of Portraiture

Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 (e): 2395-7247 Vol. VIII. 2016 IMPACT Factor - 3.9651 Rembrandt: a Milestone of Portraiture Syed Ali Jafar Assistant Professor Dept. of Painting, D.S. College, Aligarh. Email: [email protected] Abstract When we talk about portraiture, the name of Dutch painter Rembrandt comes suddenly in our mind who was born in 1607 and studied art in the studio of a well known portrait painter Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam. Soon after learning all the basics of art, young Rembrandt established himself as a portrait painter along with a reputation as an etcher (print maker). As a result, young and energetic Rembrandt established his own studio and began to apprentice budding artist almost his own age. In 1632, Rembrandt married to Saskia van Ulyenburg, a cousin of a well known art dealer who was not in favour of this love marriage. Anyhow after the marriage, Rembrandt was so happy but destiny has written otherwise, his beloved wife Saskia was died just after giving birth to the son Titus. Anyhow same year dejected Rembrandt painted his famous painting „Night Watch‟ which pull down the reputation of the painter because Rembrandt painted it in his favourite dramatic spot light manner which was discarded by the officers who had commissioned the painting. Despite having brilliant qualities of drama, lighting scene and movement, Rembrandt was stopped to obtain the commission works. So he stared to paint nature to console himself. At the same time, Hendrickje Stoffels, a humble woman who cared much to child Titus, married Rembrandt wise fully and devoted her to reduce the tide of Rembrandt‟s misfortune. -

MAGIS Brugge

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 7 Article 3 Issue 2 Cartographic Styles and Discourse 2018 MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th- century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt Musea Brugge and Kenniscentrum vzw, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Vernackt, Elien. "MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization." Artl@s Bulletin 7, no. 2 (2018): Article 3. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Cartographic Styles and Discourse MAGIS Brugge: Visualizing Marcus Gerards’ 16th-century Map through its 21st-century Digitization Elien Vernackt * MAGIS Brugge Project Abstract Marcus Gerards delivered his town plan of Bruges in 1562 and managed to capture the imagination of viewers ever since. The 21st-century digitization project MAGIS Brugge, supported by the Flemish government, has helped to treat this map as a primary source worthy of examination itself, rather than as a decorative illustration for local history. A historical database was built on top of it, with the analytic method called ‘Digital Thematic Deconstruction.’ This enabled scholars to study formally overlooked details, like how it was that Gerards was able to balance the requirements of his patrons against his own needs as an artist and humanist Abstract Marcus Gerards slaagde erin om tot de verbeelding te blijven spreken sinds hij zijn plan van Brugge afwerkte in 1562. -

Rembrandt, Vermeer and Other Masters of the Dutch Golden Age at Louvre Abu Dhabi

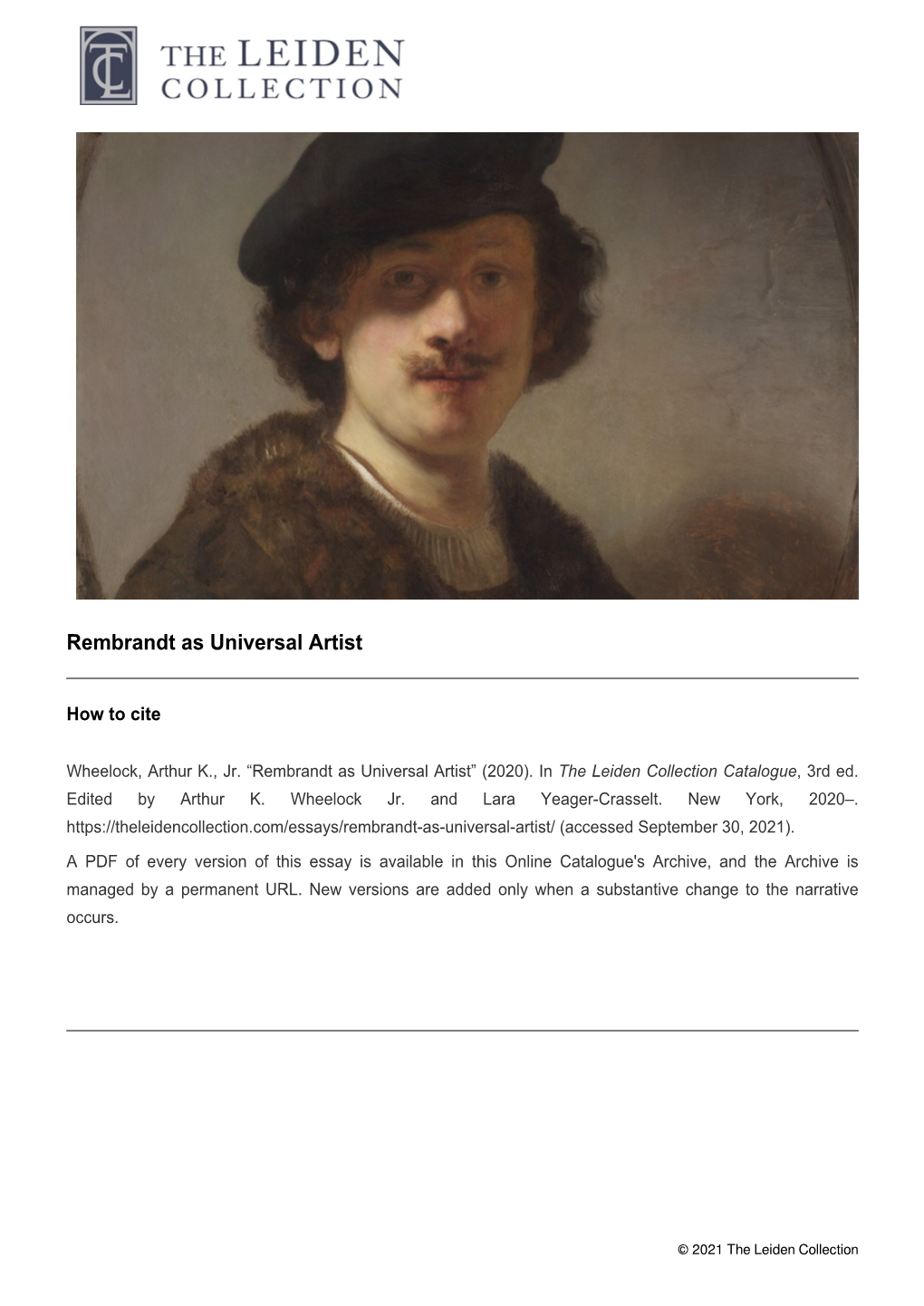

REMBRANDT, VERMEER AND OTHER MASTERS OF THE DUTCH GOLDEN AGE AT LOUVRE ABU DHABI SOCIAL DIARY | FEBRUARY, 2019 From 14 February to 18 May 2018, Louvre Abu Dhabi will present Rembrandt, Vermeer and The Dutch Golden Age: Masterpieces from The Leiden Collection and the Musée du Louvre. Jan Lievens (1607-1674) Boy in a Cape and Turban (Portrait of Prince Rupert of the Palatinate) ca. 1631 Oil on panel New York, The Leiden Collection Image courtesy of The Leiden Collection, New York. Marking the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, this new exhibition at Louvre Abu Dhabi is the largest showing to date in the Gulf Region of works by Dutch 17th-Century masters. This exhibition is the result of a remarkable collaboration of Louvre Abu Dhabi, The Leiden Collection, The Musée du Louvre and Agence France-Museums who have worked very closely to showcase this extraordinary assemblage of 95 paintings, drawings and objects. Also a rare opportunity to see 16 remarkable paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn, along with rare pieces by Johannes Vermeer, Jan Lievens or Carel Fabritius. Not familiar with The Dutch Golden Age? It was a brief period during the 17th century when the Dutch Republic, newly independent from the Spanish Crown, established itself as a world leader in trade, science and the arts, and was regarded as the most prosperous state in Europe. During this period, Rembrandt and Vermeer established themselves at the forefront of a new artistic movement characterized by a deep interest in humanity and daily life. This exhibition is drawn primarily from The Leiden Collection, one of the largest and most significant private collections of artworks from the Dutch Golden Age. -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Rembrandt Van Rijn Dutch / Holandés, 1606–1669

Dutch Artist (Artista holandés) Active Amsterdam / activo en Ámsterdam, 1600–1700 Amsterdam Harbor as Seen from the IJ, ca. 1620, Engraving on laid paper Amsterdam was the economic center of the Dutch Republic, which had declared independence from Spain in 1581. Originally a saltwater inlet, the IJ forms Amsterdam’s main waterfront with the Amstel River. In the seventeenth century, this harbor became the hub of a worldwide trading network. El puerto de Ámsterdam visto desde el IJ, ca. 1620, Grabado sobre papel verjurado Ámsterdam era el centro económico de la República holandesa, que había declarado su independencia de España en 1581. El IJ, que fue originalmente una bahía de agua salada, conforma la zona costera principal de Ámsterdam junto con el río Amstel. En el siglo XVII, este puerto se convirtió en el núcleo de una red comercial de carácter mundial. Gift of George C. Kenney II and Olga Kitsakos-Kenney, 1998.129 Jan van Noordt (after Pieter Lastman, 1583–1633) Dutch / Holandés, 1623/24–1676 Judah and Tamar, 17th century, Etching on laid paper This etching made in Amsterdam reproduces a painting by Rembrandt’s teacher, Pieter Lastman, who imparted his close knowledge of Italian painting, especially that of Caravaggio, to his star pupil. As told in Genesis 38, the twice-widowed Tamar disguises herself to seduce Judah, her unsuspecting father-in-law, whose faithless sons had not fulfilled their marital duties. Tamar conceived twins by Judah, descendants of whom included King David. Judá y Tamar, Siglo 17, Aguafuerte sobre papel acanalado Esta aguafuerte creada en Ámsterdam reproduce una pintura del maestro de Rembrandt, Pieter Lastman, quien impartió su vasto conocimiento de la pintura italiana, en especial la de Caravaggio, a su discípulo estrella. -

Best Landmarks in Amsterdam"

"Best Landmarks in Amsterdam" Created by: Cityseeker 20 Locations Bookmarked De Nieuwe Kerk "Spectacular Architecture" The Nieuwe Kerk is a 15th-century building, partly destroyed and refurbished after several fires. Located in the bustling Dam Square area of the city, this historic church has held a prominent place in the country's political and religious affairs over the centuries. It has been the venue for coronations of kings and queens, and also plays host to an array of by Dietmar Rabich exhibitions, concerts and cultural events. Admire its Gothic architecture, splendid steeples, glass-stained windows and ornate detailing. +31 20 638 6909 www.nieuwekerk.nl [email protected] Dam Square, Amsterdam Royal Palace of Amsterdam "The Royal Residence" Amsterdam's Royal Palace is the crown jewel of the city's cache of architectural marvels from the Dutch Golden Age. The palace was originally constructed in the 17th Century as the new Town Hall, designed by Jacob van Campen as a symbol of the Netherlands' far-reaching influence and its hefty stake in global commerce at that time. The palace by Diego Delso is an embodiment of opulence and lavish taste, generously adorned with marble sculptures, vivid frescoes and sparkling chandeliers that illuminate rooms of palatial proportions. Within, are numerous symbolic representations of the country's impressive economic and civic power in the realm of world politics in the 17th Century, including a larger-than-life statue of Atlas. In 1806, Louis Napoleon, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, was named King Louis I of Holland, transforming the former Town Hall into his Royal Palace. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

A Day in Amsterdam"

"A Day in Amsterdam" Created by: Cityseeker 16 Locations Bookmarked De Nieuwe Kerk "Spectacular Architecture" The Nieuwe Kerk is a 15th-century building, partly destroyed and refurbished after several fires. Located in the bustling Dam Square area of the city, this historic church has held a prominent place in the country's political and religious affairs over the centuries. It has been the venue for coronations of kings and queens, and also plays host to an array of by Dietmar Rabich exhibitions, concerts and cultural events. Admire its Gothic architecture, splendid steeples, glass-stained windows and ornate detailing. +31 20 638 6909 www.nieuwekerk.nl [email protected] Dam Square, Amsterdam Royal Palace of Amsterdam "The Royal Residence" Amsterdam's Royal Palace is the crown jewel of the city's cache of architectural marvels from the Dutch Golden Age. The palace was originally constructed in the 17th Century as the new Town Hall, designed by Jacob van Campen as a symbol of the Netherlands' far-reaching influence and its hefty stake in global commerce at that time. The palace by Diego Delso is an embodiment of opulence and lavish taste, generously adorned with marble sculptures, vivid frescoes and sparkling chandeliers that illuminate rooms of palatial proportions. Within, are numerous symbolic representations of the country's impressive economic and civic power in the realm of world politics in the 17th Century, including a larger-than-life statue of Atlas. In 1806, Louis Napoleon, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, was named King Louis I of Holland, transforming the former Town Hall into his Royal Palace.