The Potential for Legal Music Use in Podcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comeseetv Streaming Guide and Proposal

ComeSeeTv USA, Inc ComeSeeTv Streaming Guide and Proposal Cultural Live Streaming Done Right! ComeSeeTv – Can You See Me Now! 1 ComeSeeTv streaming proposal About Us ComeSeeTv is all of the following three things: First it is a global video content delivery platform that allows anyone to reliably stream their video content. Next, a website that pulls the individual channels of all our members to one place to increase the visibility of their content. Third, we are an agent for cultural development and unity across the Caribbean. When patrons pay to watch live streams on ComeSeeTv they are directly supporting the event organizer, or community! Why we’re different: Our webcasting solution concentrates on the viewer and is usually mixed live by a creative professional, so in essence our video stream experience looks and feels more like a TV production which our collective cultures deserve. Plus, though we are primarily a content delivery network service provider, we assign our global agents to oversee every stream of our clients, and to offer technical support to your customers. Nonetheless, ComeSeeTv was not designed to and does not compete with local streaming service providers in any country as our primary business is content delivery. Our streaming website is extremely secure and can be suited to match your business model as closely as possible. We are also able to handle the high visitor loads associated with all your events. Many local streaming service providers around the Caribbean are currently using ComeSeeTv to deliver video to their clientele 24/7. Four Main Package Offers 1. Event Streaming Using the very latest video mixing technology we can simultaneously project, live stream and record your event. -

IATSE LOCAL 16 CURRENT CONTRACT Theatrical Workers

2016 PROJECT COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BETWEEN CITY & COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AND INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE OF THEATRICAL STAGE EMPLOYEES, MOVING PICTURE TECHNICIANS, ARTISTS AND ALLIED CRAFTS OF THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND CANADA LOCAL N0.16 Local 16 l.A.T.S.E. 240 Second Street, First Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 Tel: 415-441-6400 Fax: 415-243-0179 www.local16.org XX TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. GENERAL PROVISIONS 4 A. Witnesseth 4 B. Recognition 4 C. Scope and Jurisdiction 4 D. Compensation 4 E. Rules and Regulations 5 F. New Categories and Classifications 5 II. DEFINITIONS 5 A. Rigging 5 B. Head of Department Rate 5 C. Multi-Source Technology 6 D. Multi-Source Technician 6 E. Computer Software Technician 7 F. General Computer Technician 7 G. General Audio Visual 7 H. Steward 7 I. Base Rate 7 J. Moscone Center Exhibit Booths Only 7 Ill. CONDITIONS 8 A. Work Week 8 B. Hourly Wage Calculations 8 C. Minimum Calls 8 D. Straight Time 8 E. Nine Hour Rest Period 8 F. Time and One-Half Rate 8 G. Double Time Rate 9 H. Un-Worked Hours 9 I. Vacation Pay 9 J. Meal Periods 9 K. Higher Scale 1O L. Holidays 1O M. Rates and Conditions 10 N. Cancellation of Calls 10 IV. FRINGE BENEFITS, WORK FEES AND PAYROLL 10 A. Health and Welfare 1O B. Pension 11 C. Check-Off Work Fees 11 D. Training and Certification Program Employer Contribution 11 E. Sick Leave 11 F. Reporting of Fringe Benefits and Work Fees 11 G. -

Navigating the Tangled Web of Webcasting Royalties

To make matters more complicated, Navigating the Tangled Web most recorded songs also have multiple copyright owners. Songwriters, compos- of Webcasting Royalties ers, and publishers of a musical composi- tion (a “song”) have rights in the song. BY CYDNEY A. TUNE AND CHRISTOPHER R. LOCKARD For example, these owners have the right to receive royalties every time a copy of the song is sold in sheet music form or ver since Napster launched to Services such as iTunes sell permanent as part of an album, as well as when the enormous popularity in 1999 and downloads and ringtones that consum- song is broadcast over the radio, the In- Edrew the ire of heavy metal band ers download to their computers and ternet, speakers in a restaurant, or when Metallica, the record industry has looked cell phones. Other companies, such as it is performed in a concert. Addition- at online music with a highly suspicious Amazon.com, sell physical phonorecords ally, artists who perform on a recorded and combative eye. The last decade has (like records and CDs). Music is also version of a song (a “sound recording”), seen record labels fight numerous Web contained in other online content, such and the owner of the copyrights in that sites and software makers that have fa- as podcasts, commercials, and videos car- sound recording (generally the record cilitated the distribution of online music ried on Web sites like YouTube. Finally, label), also have the right to receive and even individuals who simply shared thousands of Web sites, known as web- royalties for sales of that sound recording or downloaded music. -

Complete Career Resume

COMPLETE CAREER RESUME CONTACT INFORMATION: Roger Shimomura 1424 Wagon Wheel Road Lawrence, Kansas 66049-3544 Tele: 785-842-8166 Cell: 785-979-8258 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rshim.com EDUCATION: Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, M.F.A., Painting, 1969 University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, B.A., Commercial Design, 1961 Also attended: Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, Painting, (Summer), 1968 Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, Painting, (Summer), 1967 Cornish School of Allied Arts, Seattle, Washington, Illustration, (Fall), 1964 HONORS AND AWARDS: Personal papers being collected by the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Hall of Fame, Garfield Golden Graduate, Garfield High School, Seattle, Washington, June, 2013 Artist-in-Residence, New York University, Asian Pacific American Institute, New York City, New York, September 2012-May, 2013 Commencement address, Garfield High School, Seattle, Washington, June, 2012 150th Anniversary Timeless Award, University of Washington College of Arts & Sciences , Seattle, Washington, May, 2012 Designated U.S.A.Fellow in Visual Arts, Ford Foundation, Los Angeles, California, December, 2011 Honoree: "Exceptional Person in Food, Fashion and the Arts", Asian American Arts Alliance, New York City, New York, October, 2008 Community Voice Award, "Unsung Heros of the Community", International Examiner, Seattle, Washington, May, 2008 First Kansas Master Artist Award in the Visual Arts, Kansas Arts Commission, Topeka, Kansas, January, 2008 Distinguished -

An Introduction to Internet Radio

NB: This version was updated with new Internet Radio products on 26 October 2005 (see page 8). INTERNET RADIO AnInternet introduction to Radio Franc Kozamernik and Michael Mullane EBU This article – based on an EBU contribution to the WBU-TC Digital Radio Systems Handbook – introduces the concept of Internet Radio (IR) and provides some technical background. It gives examples of IR services now available in different countries and provides some guidance for traditional radio broadcasters on how to adapt to the rapidly changing multimedia environment. Traditionally, audio programmes have been available via dedicated terrestrial networks broad- casting to radio receivers. Typically, they have operated on AM and FM terrestrial platforms but, with the move to digital broadcasting, audio programmes are also available today via DAB, DRM and IBOC (e.g. HD Radio in the USA). However, this paradigm is about to change. Radio programmes are increasingly available not only from terrestrial networks but also from a large variety of satellite, cable and, indeed, telecommunications networks (e.g. fixed telephone lines, wire- less broadband connections and mobile phones). Very often, radio is added to digital television plat- forms (e.g. DVB-S and DVB-T). Radio receivers are no longer only dedicated hi-fi tuners or portable radios with whip aerials, but are now assuming the shape of various multimedia-enabled computer devices (e.g. desktops, notebooks, PDAs, “Internet” radios, etc.). These sea changes in radio technologies impact dramatically on the radio medium itself – the way it is produced, delivered, consumed and paid-for. Radio has become more than just audio – it can now contain associated metadata, synchronized slideshows and even short video clips. -

Making TELEVISION ACCESSIBLE REPORT NOVEMBER 2011 Making a TELEV CCESS DIGITAL INCLUSION Telecommunication Developmentsector NOVEMBER 2011 Report I

DIGITAL INCLUSION International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau OVEMBER 2011 N Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 Making Switzerland www.itu.int TELEVISION ACCESSIBLE Report REPORT BLE I CCESS A N O I S I NOVEMBER 2011 Printed in Switzerland MAKING TELEV Telecommunication Development Sector Geneva, 2011 11/2011 Making Television Accessible November 2011 This report is published in cooperation with G3ict – The Global Initiative for Inclusive Information and Communication Technologies, whose mission is to promote the ICT accessibility dispositions of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities www.g3ict.org. ITU and G3ict also co-produce the e-accessibility Policy Toolkit for Persons with Disabilities www.e-accessibilitytoolkit.org and jointly organize awareness raising and capacity building programmes for policy makers and stakeholders involved in accessibility issues around the world. This report has been prepared by Peter Olaf Looms, Chairman ITU-T Focus Group on Audiovisual Media Accessibility. ITU 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. Making Television Accessible Foreword Ensuring that all of the world’s population has access to television services is one of the targets set by world leaders in the World Summit on the Information Society. Television is important for enhancing national identity, providing an outlet for domestic media content and getting news and information to the public, which is especially critical in times of emergencies. Television programmes are also a principal source of news and information for illiterate segments of the population, some of whom are persons with disabilities. -

Webcast Studio

EVENT SERVICES WEBCAST STUDIO OVERVIEW Webcast Studio Self or managed service solution to broadcast interactive presentations Webcast Studio provides unrivaled technology that makes it easy to create and broadcast impactful, rich media presentations on the web. Connect with more people around the globe, no matter where they are. Rich Media Streaming Most Powerful & Global Webcast Studio delivers webcasts with The most powerful webcasting solution crystal clear audio, video, and slides for in the market with new capabilities to What it means for you: an unmatched attendee experience. support up to 17 languages, Experience the highest quality video multilingual close captioning for over • Reach wider audiences 150 languages and a connection to a stream without additional encoding • Lower production and global content delivery network hardware. Presenters can handle multiple broadcast costs slide decks with animations and builds. solution to cater to your global The webcast studio can accept any video audience. Create detailed micro-sites • More engaged attendees input allowing you the flexibility to deliver with multiple themes, tabs, and social • Shorter time to market the most compelling content to make media url’s. your presentation come to life. Why customers choose Webcast Detailed Analytics Studio Webcasting Made Easy Detailed analytics to track attendance, • Multiple options for multiple demographics and even behavior audiences Users can enjoy the fastest self-service inside the presentation. The • Easy to use self service option solution available in the industry. While Engagement Index allows organizers all of your participants need is access to to define parameters and criteria to • Speed – set up a webcast in a web browser to view presentations Built measure lead scoring, attendee seconds on Adobe Flash, Webcast Studio makes engagement, content and overall • 100% web based – no downloads it easy for them to join from virtually success of their event. -

Webcasting Overview.Pdf

What is Webcasting? A webcast is a media file distributed over the Internet using streaming media technology. A webcast may either be distributed live or on demand. Essentially, webcasting is “broadcasting” over the Internet. Think of it as TV on the Internet, the similarity being that one message is broadcast to many viewers. It is different however, in that each viewer has a connection back to the point of delivery, or the server. There are two scenarios: Live and Archive (sometimes referred to as Video on Demand, or VOD). Each requires the following: Video origin -> Video Server -> Video Player When live, the Video origin is an encoder that basically compresses the video as it receives it from a camera or VCR/DVD and sends this compressed stream to a Server. The Server is capable of duplicating that single stream into many streams, which is what the Player connects to. The Player is the software that is on the computer of the person who wishes to watch the video, and uses the computer monitor and speakers to present the video to the viewer. For Archive, or VOD, the video is previously captured and usually edited, then compressed to the streaming format and placed on the server. From here the Server delivers the stream to the Player, when the user clicks on a link. This is the essence of webcasting - taking video from a point of origin and delivering it to many viewers, using the Internet. Reasons to Webcast • Dramatically widen access to information and events • The connection made by audio and video is unparalleled. -

Description of Methodology for Webcast Metrics

Description of Methodology for Webcast Metrics and Webcast Metrics Local BY TRITON DIGITAL Publication Information © 2020 Triton Digital. All rights reserved. Published by Triton Digital. All Rights Reserved. 1440 Ste-Catherine W, Suite 1200 Montreal QC H3G 1R8 Canada 514-448-4037 www.tritondigital.com Document Version Description of Methodology – Webcast Metrics and Webcast Metrics Local Document Version 4 Trademarks TRITON DIGITAL and WEBCAST METRICS are registered trademarks of Triton Digital Canada Inc. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. Disclaimer Notice No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, translated into any other language in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, for any purpose, without the express permission of Triton Digital. Triton Digital has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information contained herein. However, due to continuing product development, the information is subject to change without notice. Customer Support https://support.tritondigital.com/ TRITON DIGITAL | Description of Methodology – Webcast Metrics® & Webcast Metrics Local (v4) Page 2 Contents 1. Overview....................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Products and Services Included .......................................................................................... 5 1.2. Products and Services Not Included .................................................................................. -

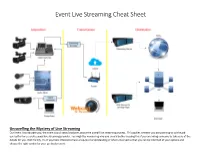

Event Live Streaming Cheat Sheet

Event Live Streaming Cheat Sheet Unravelling the Mystery of Live Streaming Our intent is to educate you, the event coordinator/producer, about the overall live streaming process. This applies whether you are planning to do the job yourself or hire a professional live streaming provider. You might be wondering why you should bother reading this if you are hiring someone to take care of the details for you. Well frankly, it’s in your best interest to have a top-level understanding of what’s involved so that you can be informed of your options and choose the right vendor for your particular event. The Live Streaming Process In its simplest form, the live streaming process can be divided into three phases: Acquisition, Transmission, and Distribution (refer to the diagram above). If you follow the signal flow via the arrows on the diagram, it looks fairly simple except perhaps understanding what some of those components are doing. Keep in mind that there are many variations that are possible with the signal path. What’s shown here is the most straight-forward concept for sake of illustration. So let’s take a closer look at each phase and discover the important take-aways. Acquisition This is the front-end production side which includes the cameras, microphones, PowerPoint images, pre- recorded videos, titles, graphics, and video switcher. In short, all the equipment and crew that make your event look and sound like a professional television broadcast. All the various input devices end up being routed to the video switcher which cuts between cameras, adds video effects and in many cases adds the graphic elements as well. -

Media Fusion and Future TV: Examining Multi-Screen TV Convergence in Singapore

1 Media fusion and future TV: examining multi-screen TV convergence in Singapore Trisha T.C. Lin Assistant Professor, Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, [email protected] Abstract This study examines Singapore’s national media blueprint and industry stakeholders’ coping strategies in response to multi-screen TV development. The findings show Singapore muti-screen TV development is still at a nascent stage after launching Media Fushion and FutureTV plans in mid 2009. The policymakers play a key role to follow national media blueprint to unify the inter-industry and cross-country collaboration. TV operators and telcos are found to remediate themselves by harnessing the power of internet and mobile technologies for content innovation and distribution. To tackle the complicated convergent issues in multi-screen TV industry, this study proposes to separately regulate the technology-neutral platforms and diverse audiovisual content. It also recommends a pro-innovative policy with the light-touch licensing scheme and loose content regulation to facilitate the development of the next TV. Keywords: three-screen TV, multi-screen TV, convergence, media fusion, IPTV, mobile TV, cross-platform, TV technologies, TV market, TV policy 1. Introduction The prevalence of Internet and mobile technologies has shaped TV industry dramatically in video consumption, content creation and distribution, and business models. The convergent video technologies allow viewers to watch audiovisual content with personalized experiences cross three screens: TVs, computers, and mobile devices. Since 2009, “three-screen TV” has emerged as a trendy phrase which refers to the integrated solutions for multi-screen video consumption at anywhere, anytime (AT&T, 2010; Krazit, 2009). -

There's a Lot More to the Digital Internet Radio (Webcast)

There’s a lot more to the digital internet radio (webcast) listening experience than you may know. Obviously, the easiest way to listen is to use your smart phone or tablet to go to the station website and press the play button. The sound plays using your device’s default player and built-in speaker(s) which don’t even begin to reproduce the full quality of the webcast. Upgrade your player (optional): Player quality is important to ensure continuous, flawless playback. StreamS HiFi Radio app is a one-time $4.99 cost from iOS (iPhone) and Apple TV’s app stores, and is far and away the best player available. Don’t even bother with free players offered in the app stores or on the internet. They are difficult to use, have advertisements which interrupt use, are of poor quality, or all of these. If you don’t want to spend $4.99 for StreamS, just continue to use your device’s default player. Some of these are okay (iOS Safari), but none are great (yet). Upgrade your speaker(s): Regardless of which player you use, here are ways you can enhance your listening experience by taking advantage of the full feature set of the webcast: If you’re listening at home or at work, pair your phone or tablet to a Bluetooth speaker or earphones. This will provide an immediate improvement to the listening experience. There are a wide range of Bluetooth speakers, varying in size, quality and price. If your priority is sound quality, we recommend the Bose or Sonos lines and the Amazon Echo Plus or Echo Studio.