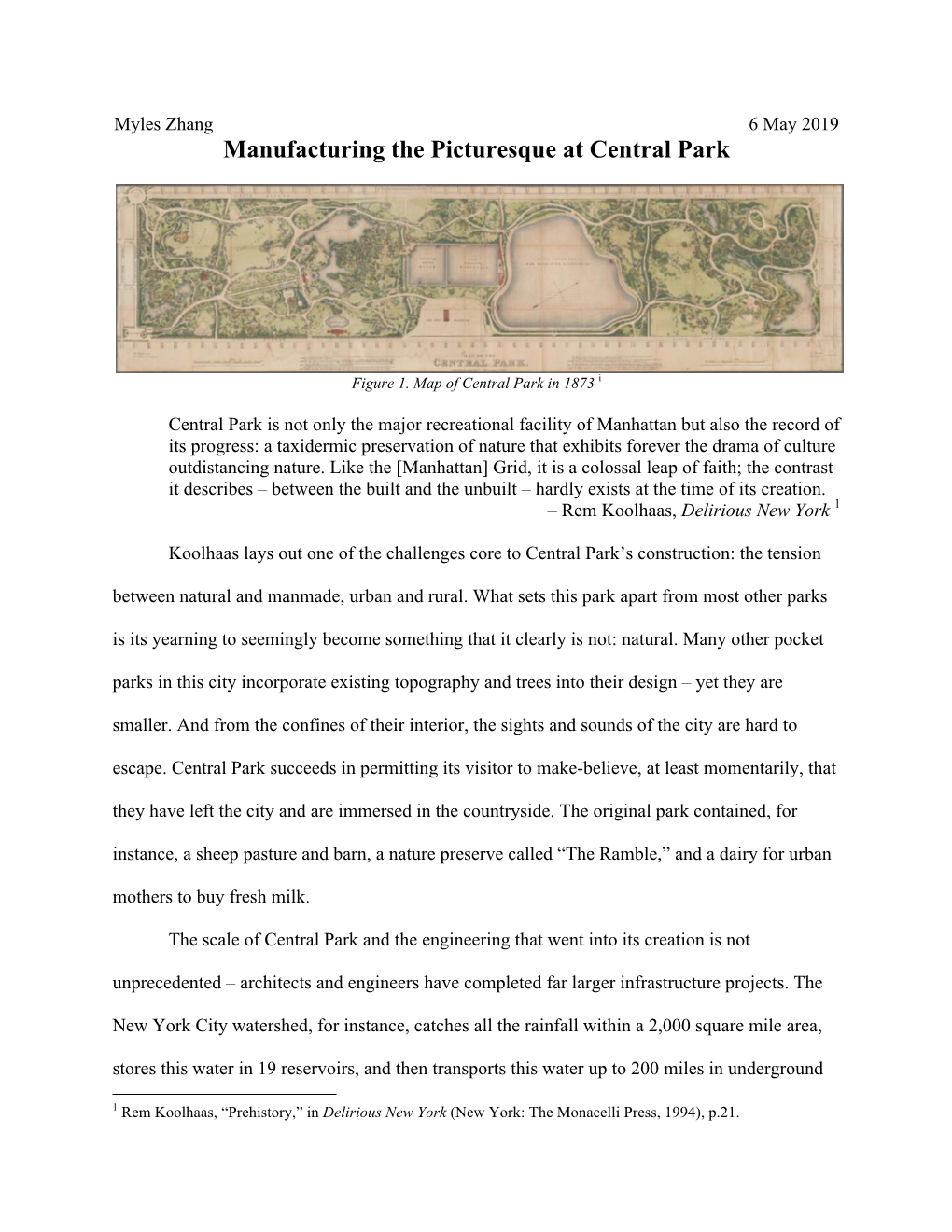

Manufacturing the Picturesque at Central Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventure Playground: Essentially, to a Place of Pleasure—That Today It Surrounds Us, Everywhere, Having Quietly John V

The city’s onscreen prominence is so taken for granted today that it is hard to imagine that as late as 1965, the last year of Robert F. Wagner’s mayoralty, New York hardly appeared in films at all. That year, only two features were shot substantially in the city: The Pawnbroker, an early landmark in the career of veteran New York director Sidney Lumet, and A Thousand Clowns, directed by Fred Coe, which used extensive location work to “open up” a Broadway stage hit of a few years earlier by the playwright Herb Gardner. The big change came with Wagner’s successor, John V. Lindsay—who, soon after taking office in 1966, made New York the first city in history to encourage location filmmaking: establishing a simple, one-stop permit process through a newly created agency (now called the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting), creating a special unit of the Police Department to assist filmmakers, and ordering all city agencies and departments to cooperate with producers and directors (1). The founding of the Mayor’s Film Office—the first agency of its kind in the world—remains to this day one of the Lindsay administration’s signal achievements, an innovation in governance which has been replicated by agencies or commissions in almost every city and state in the Union, and scores of countries and provinces around the world. In New York, it helped to usher in a new industry, now generating over five billion dollars a year in economic activity and bringing work to more than 100,000 New Yorkers: renowned directors and stars, working actors and technicians, and tens of thousands of men and women employed by supporting businesses—from equipment rental houses, to scenery shops, to major studio complexes that now rival those of Southern California. -

TOOLKIT for CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-Imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great

MONUMENTAL WOMEN’S TOOLKIT FOR CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great Women’s History Month, March 2021 Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument Photo Credit: NYC Parks/Daniel Avila © Monumental Women 2021 – All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Introduction 1 A Framework For Structure, Accounting, Budgeting And Taxation 5 Suggestions For Launching A Women’s History Education Campaign 12 Intergenerational Leadership: Inspiring Youth Activism 16 Creating And Amplifying Partnerships 19 Fundraising Tips 22 Other Fundraising Issues To Consider 28 Publicity And Marketing: Public Relations 33 A Happy Ending 37 Welcome to Monumental Women’s Toolkit for Change! This document was created by members of the Board of Monumental Women with experience and expertise in particular areas of the process of honoring more women and people of color in public spaces. We hope that the information contained in the Toolkit will serve as a guide to others who are embarking on their own eforts to reimagine their communities’ public spaces. Officers and Board Members: President - Pam Elam Vice President for Operations - Namita Luthra Vice President for Programs - Brenda Berkman Secretary - Ariel Deutsch Treasurer - David Spaulding Judaline Cassidy Gary Ferdman Coline Jenkins Serina Liu Eileen Macdonald Meridith Maskara Myriam Miedzian Heather Nesle Monumental Women thanks ongoing partner Jane Walker by Johnnie Walker, the first-ever female iteration of the Johnnie Walker Striding Man and a symbol of progress in gender equality, for its support of our project and collaboration in bringing this Toolkit to fruition. Introduction INTRODUCTION By Pam Elam, Monumental Women President It's not often that you have the chance to be part of something truly historic. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work. -

Extended to March 11, 1966

PRESS RELEASES - JANUARY, FEBHUARY, MRCH, APRIL - 1966 Page APPLICATION Re-opening of Season Help Applications - 1 extended to March 11, 1966 AU GOGO - First event of season at Mall - Sat., April 23, BUDGETS - Park Commissioner Hovings remarks at Capital Budget hearings 2/16/66 Park Commissioner Hovings remarks about closing of Heckscher Playground, Children's Zoo and Carl Schurz Park if P.D. does not get fair share of city's Expense Budget this year. BROADWAY SHOW LEAGUE Opening Day (nothing done—not our release) CHESS TOURNAMENT - Entry blanks for boys and girls 17 yrs and under at 6 62nd St. and Central Park. Chess Program sponsored by Amer. Chess Foundation 6 A CURATORS Prospect Park and Central Park appointed by Comm. 7 and Staff members. Five biogs. added DUTCH STREET ORGAN - 4 Dutch organizations in New York cooperated in 8 bringing organ to Central Park. EASTER CANDY HUNTS - Sponsored by Quaker City Chocolate and Confectionery 9 Company at various locations in 5 boros, April 13. EGG ROLLING Contest - sponsored by Arnold Constable-Fifth Ave, 10 Saturday afternoon, April 9. Douglaston Park Golf Course, Wed., April 13 - Prizes 11 donated by Douglaston Steak House, GOLF Pelham Bay Park Golf Driving Range, Pelham Bay Park 12 facility open starting Sat., April 2, 1966. Courses open for seaon on Saturday, April 2, 1966, at 13 6 a.m., Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Richmond GOLDEN AGE Joe and Alice Nash, dancers. J. Hood Wright Golden Age 14 Center to entertain with 20 dancers at the Hebrew Home for the aged, on Fri. 1/18/66 Winter Carnival - Sat., Jan. -

Seeing Central Park Again for the First Time by Bike

Seeing Central Park Again For the First Time By Bike When I, Shawn Barton, moved to the Miami Area 10 years back, I thought I had already seen NYC’s attractions and explored my former “backyard” quite thoroughly. But I had never gone on a bike tour of Central Park. Biking in Central Park (Image: Flickr/Dave Winner, Last spring, I returned to Brooklyn to visit friends and relatives and see my old home again; and I went with an old friend on a bike tour in Central Park. I never knew how much I had missed. It was like seeing the park again for the first time. To learn more about how to book your own Central Park bike tour, visit bikerentalscentralpark.com – tours of the park for great price points. Read on to learn about what a bike tour has to offer! My Central Park Bike Tour It was simple, fast, and affordable to rent our bikes, along with helmets, locks, and all accompanying equipment. And just peddling over the grassy, rolling hills and past the blooming cherry blossom trees was exhilarating. The gorgeous nature with skyscrapers looming in the background is a truly unique sight. The Strawberry Fields (Image: nycgovparks.org) One of the first stops we made was at The Strawberry Fields, where we both appreciated this rustic preserve of the original park’s looks and the Beatles John Lennon to whom these acres are dedicated. But this was only one among numerous stops full of natural beauty. We stopped to stroll at Central Park Mall where we got panoramic views and a chance to watch artists and singers perform. -

September 2019

CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 10 215 West 125th Street, 4th Floor—New York, NY 10027 T: 212-749-3105 F: 212-662-4215 CICELY HARRIS Chairperson PARKS AND RECREATION COMMITTEE MINUTES Wednesday, September 11th, 2019, 6:30pm SHATIC MITCHELL Hon. Karen Horry, Chair District Manager Meeting began at 6:32 pm and was held in the 4th Floor Conference room. The meeting was chaired by Hon. Karen Horry, Chair. Committee Members in Attendance: Chair Karen Horry, Kevin Bitterman, Karen Dixon and Barbara Mason Committee Members Excused: Eboni Mason Committee Members Absent: Seitu Jamel Hart, Tiffany Reaves, Derrick Perkinson and Deborah Gilliard. Guests in attendance: Lane Addonizio (Central Park Conservancy), John D. (Mitchell Giurgola), Christopher Nolan (Central Park Conservancy), John T. Reddick (Central Park Conservancy), Grey Elam (Central Park Conservancy), Susie Rodriguez (Central Park Conservancy) Mia’s Dayson (LTACT Communications), Makela Watkins (Central Park Conservancy), Brenda Ratliff (121 St. Nicholas), Mitchel Loring (NYC Parks), Erica Bilal (NYCEDC), Waheera Marsalis (NYCEDC), D. Glaude (LTACT - Tennis), Isabel Samuel, Steve Simon (NYC Parks), Penelope Cox (MBP), Pam Elam PRESENTATIONS: A. Central Park Conservancy - Meer Lasker Pool The landmarked Central Park’s Lasker pool and ice rink is in need of a major makeover. The proposed project will be funded collectively by the Central Park Conservancy and the city. The project will warrant the pool and rink closure due to construction for three years. The reconstruction will better connect the North Woods and the Harlem Meer, both currently blocked from one another by the rink. Donald Trump’s company, the Trump Organization, runs the skating rink, but their concession expires in 2021. -

42671968 Press Releases Part4.Pdf

1743 Large Sculpture Exhibited at 60th Street and Fifth Ave, 744 Halloween Stilt Walk on Central Park Mall 10/l6/68 745 lee Hookey Clinics at the Lastor Hink 10/2l/68 746 Paseo de Sanoos en el Parque Central 10/22/68 747 Baby Llama born on October 17th 10/22/68 748 Closing of Children's Zoo in Central Park 10/23/68 749 David Vasques - Olympic Contender 10/24/68 750 Inergeney Meeting Of Cultural Institutions 10/25/68 Schedule 7S0A Cultural Institutions Waive Fees and/special Programs H/4/68 751 Celebration Of 29th Street Mural H/4/68 752 Giant Tinker Toys in Central Park 753 Publio and Private Cultural Institutions Expand Programs 11/8/68 During School Crisie Department of Cultural Affairs CityofNewYork Administration of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Arsenal, Central Park 10021 UPON RECEIPT LARGE SCULPTURE TO BE EXHIBITED AT 60TH STREET AND FIFTH AVE. "NEW YORK I", a large abstract sculpture by Anthony Padovano, will be installed at 60th Street and Fifth Avenue on Thursday, October 17th at 11:00 a. m, announced August Heckscher, Administrator of Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs. Made of plywood, epoxy resin and enamel, the work measures 12* X 201 X 10' and is painted ultra-marine blue. Sculptor Padovano was born in New York City in 1933. He is represented by the Bertha Schaefer Gallery where he had a one-man show in 1967. Currently, he is exhibiting with the painter, Paul Georges, at the Galerie Simonne Stern, New Orleans. Mr. Padovano has works in the Whitney Museum of American Art and many other important public and private collections. -

Park Board Department of Parks

MINUTES OF THE PARK BOARD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PARKS OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1924 Commissioner FRANCIS D. GALLATIN, (President) JOSEPH P. HENNESSY EDWARD T. O'LOUGHLIN ALBERT C. BENNINGER JOHN J. O'ROURKE WILLIS HOLLY, Secretary \ M. B. Brown Printing & Binding Co., 37-41 Chambers Street, N. Y. 31-2001-25-B I \ INDEX A PAGE Adams, Edward F., Brooklyn, Bushwick Playground, steps, bid received ....... 80 Ah'ord & Swift, Manhattan, American Museum of Natural History, heating and ventilating, bid received ............................................... 41 Alterations, Manhattan, American Museum of Natural History, central gallery, bids received ................................................. 56 To Comptroller, for approval. .................................... 56 Queens, Jacob Riis, Seaside Park, approved ............................. 71 American Federation of Musicians, park music ............................. 33 American Museum of Natural History, Manhattan, central gallery, alterations, bids received ................................................ 56 To Comptroller, for approval ...................................... 56 Construction, southeast wing, extension of time ......................... 71 Electric generating plant, contracts A, B, C, D, E, bids received ......... 35 To Comptroller, for approval ..................................... 51 Elevators, extension of time ........................................... 49,78 Improvement, bird hall, bids received .................................. 63,72 To -

P a R T M E N Parks Arsenal, Central Park Regent 4-1000

DEPARTMEN O F P ARK S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4- I 00 0 FOR RELEAS^^E^ IMMEDIATELY l-l-l-60M-706844(61) ^^^ 114 NewboTd Morris, Commissioner of Parks, announces that the seven Christmas week Marionette performances of "Alice in Wonderland", scheduled to be held in the Hunter College Playhouse, have been over- subscribed and the public is hereby notified that no further requests for tickets can be honored. To date there have been over 15,000 requests for tickets for these free marionette performances with only 5,000 seats available for the four days. It is hoped that the many thousands of youngsters who have been denied the pleasure of seeing any of these performances, may see "Alice in Wonderland" during the winter showings at public and Paro- chial schools in the five boroughs. The travelling marionette theatre will be in the five boroughs according to the following schedule.. Until January S Manhattan Brooklyn Jan. 9 to Jan. 30 Bronx Jan. 31 to Feb. 20 Queens Feb. 26 to March 16 Richmond March 19 to March 27 •\ o /on DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE IMMEDIATELY l-l-l-60M-706844(61) «^»* 114 NewboTd Morris, Commissioner of Parks, announces that the seven Christmas week Marionette performances of "Alice in Wonderland", scheduled to be held in the Hunter College Playhouse, have been over- subscribed and the public is hereby notified that no further requests for tickets can be honored. To date there have been over 15,000 requests for tickets for these free marionette performances with only 5,000 seats available for the four days. -

Download Itinerary

CYCLING Biking in New York, Cape Cod & Vermont 15 nights TOUR OVERVIEW Open your tour with three nights in New York City and experience the vibrancy of The Big Apple. Visit iconic sites on foot and by bike - Times Square, the Brooklyn Bridge, Central Park and many more. We will also have time to catch a Broadway show if you wish. Moving on to Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, you will cycle easy paths past scenic lighthouses, gingerbread cottages and dramatic sea vistas. Discover what makes Martha’s Vineyard such a favourite with artists, writers and American Presidents. Following some spectacular coastal riding, we move on to the glorious fall colours of Vermont. Every day will feature leisurely lakeside cycling and awe inspiring views of Lake Champlain. Our rides will be on the Burlington bike path and quiet back roads, through charming New England towns all the while staying in cosy inns and boutique hotels. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS • Three nights in New York City • Visit tranquil islands – made for cycling, with exhilarating oceanside rides, dramatic vistas, ferry crossings and scenic lighthouses • See what makes Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard a favourite of writers, artists and US Presidents • Experience the beautiful fall colours, lakeside splendour and rich his- tory of Vermont • Enjoy the small town hospitality and culture of the Northeastern USA • Enjoy magnificent lake, farmland and ocean panoramas – the best way possible, on a bike • Enjoy boutique accommodation in local inns TOUR INCLUSIONS TOUR EXCLUSIONS • The services of an experienced -

BOARD of TRANSPORTATION COLLECTION" 05/25/2010 Matches 291

Collection Contains text "BOARD OF TRANSPORTATION COLLECTION" 05/25/2010 Matches 291 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Extent Date Home Location A VIIA-1 Sketch on vellum for an American Services Foundation poster one 18 1/2" x 23" 1941 Livingston Plaza Poster "Aviation Spectacle National Defense" Demonstration. sketch A VIIA-2 Poster advertising for "Unity Rally - Stop Hitler Now" and also one 11" x 14" 1941 Livingston Plaza Poster advertises speakers Senator Claude Pepper, Larry MacPhail, poster Stanley High, Edgar Mowrer, Herbert Agar, Dr. Harry Gideonse, and Frank Serri for rally event held June 6, 1941 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. A VIIA-3 Poster with blue and graphite pencil sketches for a USO benefit one 12" x 14" 1941 Livingston Plaza Poster being held at the Vanderbilt Mansion from July 3 -July 13 [1941]. poster A VIIA-4 Poster created by the Board of Education which reads "Keep Fit one 15 1/2" x 22" 1941 Livingston Plaza Poster for Defense. The Board of Education offers recreation poster opportunities 3 evenings a week from 7-10 PM in 135 school buildings, calisthenics, basketball, badminton, handball, volleyball, swimming. Auditorium and meeting facilities for clubs available. No charges in elementary schools, 25 ¢ to $1.00 in High Schools. Use New York City Transit System. Divisions of Recreation and Community Activities." Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Extent Date Home Location A VIIA-5 Poster advertising "Civilian & National Defense Exposition, Grand one 14" x 12" 1941 Livingston Plaza Poster Central Palace, Lexington Avenue, 46th to 47th Streets, Sept 20th poster to Oct 18th. -

Lighting 4 Lighting

Lighting 4 Lighting Lighting 4.0 Introduction 150 Table 4a: Poles & Luminaires 153 4.1 Standard Poles 154 4.1.1 Octagonal Pole 155 4.1.2 Davit Pole 156 4.1.3 Round Pole 157 4.2 Distinctive & Historic Poles 158 4.2.1 Alliance Pole (Type S) 159 4.2.2 Bishops Crook Pole 160 4.2.3 City Light Pole 161 4.2.4 Flatbush Avenue Pole 162 4.2.5 TBTA Pole 163 4.2.6 Type F Pole 164 4.2.7 Type M Pole 165 4.2.8 World’s Fair Pedestrian Pole 166 4.2.9 Type B Pedestrian Pole 167 4.2.10 Flushing Meadows Pedestrian Pole 168 4.3 Signal Poles 169 4.3.1 Type M-2A Signal Pole 170 4.3.2 Alliance Signal Pole (Type S) 171 4.3.3 Type S-1A Signal Pole 172 4 149 4.0 Introduction LIGHTING Introduction o Street Light Components A street light comprises three elements: 1) the base (sometimes with a “skirt” that covers the base to achieve a desired appearance), 2) the pole, and 3) the LED luminaire. Some poles can be combined with different luminaires to achieve the desired aesthetic and engineering outcomes; in other cases, the combination of pole and luminaire cannot be changed. This chapter notes the luminaires with which each pole can be paired. o Energy Standards DOT requires the use of LED luminaires for all installations. Luminaire E Houston Street, Manhattan About this Chapter This chapter, which constitutes the current DOT Street Lighting Catalogue, outlines options for street and pedestrian lighting for New York City streets, bikeways, pedestrian bridges, pedestrian malls, plazas, and parks.