Reimagining Recreation by James Trainor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Raised Wrong Educated Worse

DIBQUFS!2!! XIZ!BSF!UIFZ!TP!CBE@! § 1 ~ Products of a Flawed Socialization Process What is wrong with so many Black boys? Who is raising them to be so disrespectful? Why do they have such little regard for school and the entire educational process? Why are they so damn bad? These are the pressing questions that teachers, school staff members, parents, concerned family, and community members all across America are constantly asking. Some ask themselves, others ask their designated leaders, yet very few people are satisfied with the vague, one-sided answers that they have been getting. After reading this book, you should better understand the an- swers to these popular questions. It stands true for young Black males, just as it does for all human beings, that absolutely none of us act the way that we act out of a vacuum or simply because that’s the way that we always wanted to act. We are all social- ized first by our guardians and surrounding family mem- bers, later by school and our peers, and at all times by both our local communities and the greater society through powerful institutions such as the church, the government, the media, the entertainment industry, and civic/community organizations. Socialization is the process over time through which a child is instructed and encouraged how to act, as well as how not to act. Many factors play into whether or not an individual will accept or reject the behavioral ten- dencies that he has been trained to follow by his parents, 5 school, local community, and greater society. -

Slangs on Internet

ENGLISH SLANGS ON INTERNET Gathered by | Jasimdev A A&F Always And Forever Abercrombie & Fitch A LEVEL School exam (UK) Anal sex A/N Author's Note A/W Anyway A3 Anywhere, Any time, Any place A7A Frusration, anger (Arabic) A7X Avenged Sevenfold (band) AA Alcoholics Anonymous African-American Automobile Association AAA American Automobile Association Battery size AAB Average At Best AAF Always and Forever AAK Alive And Kicking AAMOF As A Matter Of Fact AAP Always A Pleasure AAR At Any Rate AARP American Association of Retired Persons AAWY And Also With You AAYF As Always, Your Friend AB Adult Baby ABC American Born Chinese ABD Already Been Done ABDC America's Best Dance Crew (TV show) ABDL Adult Baby Diaper Lover ABH Actual Bodily Harm ABN Asshole By Nature * ABP Already Been Posted ABS Absolutely ABT About ABT2 About To ABU Anyone but (Manchester) United AC Air Conditioning Alternating Current AC/DC Rock Band ACAB All Cops Are B*****ds ACC Actually ACCT Account ACG Asian Cowgirl ACK Disgust, frustration Acknowledgement ACLU American Civil Liberties Union ACME A Company that Makes Everything ACORN Small penis ACP Automatic Colt Pistol ACT SAT type test ACU Army Combat Uniform AD Anno Domini (in the year of our Lord) AD HOC For the specific purpose Improvised, impromptu ADD Attention Deficit Disorder ADDY Address ADGTH All Dogs Go To Heaven ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADIDAS German sportswear company All Day I Dream About Sex ADL All Day Long ADM ¡Ay Dios Mío! (Spanish -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House -

Adventure Playground: Essentially, to a Place of Pleasure—That Today It Surrounds Us, Everywhere, Having Quietly John V

The city’s onscreen prominence is so taken for granted today that it is hard to imagine that as late as 1965, the last year of Robert F. Wagner’s mayoralty, New York hardly appeared in films at all. That year, only two features were shot substantially in the city: The Pawnbroker, an early landmark in the career of veteran New York director Sidney Lumet, and A Thousand Clowns, directed by Fred Coe, which used extensive location work to “open up” a Broadway stage hit of a few years earlier by the playwright Herb Gardner. The big change came with Wagner’s successor, John V. Lindsay—who, soon after taking office in 1966, made New York the first city in history to encourage location filmmaking: establishing a simple, one-stop permit process through a newly created agency (now called the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting), creating a special unit of the Police Department to assist filmmakers, and ordering all city agencies and departments to cooperate with producers and directors (1). The founding of the Mayor’s Film Office—the first agency of its kind in the world—remains to this day one of the Lindsay administration’s signal achievements, an innovation in governance which has been replicated by agencies or commissions in almost every city and state in the Union, and scores of countries and provinces around the world. In New York, it helped to usher in a new industry, now generating over five billion dollars a year in economic activity and bringing work to more than 100,000 New Yorkers: renowned directors and stars, working actors and technicians, and tens of thousands of men and women employed by supporting businesses—from equipment rental houses, to scenery shops, to major studio complexes that now rival those of Southern California. -

Hbo Across the Bridge the Network (And Jason Schwartzman) Travel out of the City Into Our Favorite Borough Brooklyn Heights

A SPECIAL ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT TO THE NEW YORK OBSERVER Brooklyn LivingSpring 2011 BROOKLYN REAL ESTATE BOOM CELEBRITIES INHABITING THE BOROUGH HBO ACROSS THE BRIDGE THE NETWORK (AND JASON SCHWARTZMAN) TRAVEL OUT OF THE CITY INTO OUR FAVORITE BOROUGH BROOKLYN HEIGHTS Angela Ferrante Bill Sheppard CLASSIC TOWNHOUSE, COUNTRY CHARM MANHATTAN AND HARBOR VIEWS GARDEN PLACE TUDOR Bklyn Hts. Excl. Sophisticated 25’ wide home. Bklyn Hts. Excl. 1846 Greek revival. All Bklyn Hts. Excl. Single family TH on Garden Orig details thru-out, hi ceils, marble mantles, original details. Fireplaces, ceiling and Place. Renovated thoroughly and carefully with wide plank oors, 1830s hardware & 3 wbfps. crown moldings. Lovely garden. Beautifully highest quality materials and craftsmanship. Jill Braver Elegant parlor & FDR, 2 full rs of BRs & large preserved and very special. Secluded North Classic details throughout. Functional and easy lndscpd grdn & patio. $3.95M. WEB# 1214225. Heights. $3.8M. WEB# 1206356. to maintain. $3.6M WEB# 726299. Rhea Cohen 718-858-5908 Brian Lehner 718-858-5423 Brian Lehner 718-858-5423 Phyllis Norton-Towers Aileen Truesdale BEST OF ALL WORLDS PREWAR CLASSIC SEVEN RARELY AVAILABLE Bklyn Hts. Excl. 5-story, 4 family. Unique Bklyn Hts. Excl. Sprawling 4BR, 3 bath Co-op Bklyn Hts. Excl. Classic prewar 3BR, 2 bath Catherine Zito opportunity to acquire a high income- in elev bldg on quiet tree-lined Central Heights Co-op. Top r, elev bldg, coveted block. 33 producing property & live lavishly, too. Lrg rms, street. LR with wbfp. Common rfdk, basement sun-lled exposures, skyline views. Live-in beautiful proportions. $2.75M. WEB# 1197530. -

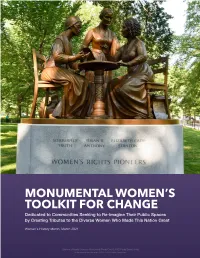

TOOLKIT for CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-Imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great

MONUMENTAL WOMEN’S TOOLKIT FOR CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great Women’s History Month, March 2021 Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument Photo Credit: NYC Parks/Daniel Avila © Monumental Women 2021 – All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Introduction 1 A Framework For Structure, Accounting, Budgeting And Taxation 5 Suggestions For Launching A Women’s History Education Campaign 12 Intergenerational Leadership: Inspiring Youth Activism 16 Creating And Amplifying Partnerships 19 Fundraising Tips 22 Other Fundraising Issues To Consider 28 Publicity And Marketing: Public Relations 33 A Happy Ending 37 Welcome to Monumental Women’s Toolkit for Change! This document was created by members of the Board of Monumental Women with experience and expertise in particular areas of the process of honoring more women and people of color in public spaces. We hope that the information contained in the Toolkit will serve as a guide to others who are embarking on their own eforts to reimagine their communities’ public spaces. Officers and Board Members: President - Pam Elam Vice President for Operations - Namita Luthra Vice President for Programs - Brenda Berkman Secretary - Ariel Deutsch Treasurer - David Spaulding Judaline Cassidy Gary Ferdman Coline Jenkins Serina Liu Eileen Macdonald Meridith Maskara Myriam Miedzian Heather Nesle Monumental Women thanks ongoing partner Jane Walker by Johnnie Walker, the first-ever female iteration of the Johnnie Walker Striding Man and a symbol of progress in gender equality, for its support of our project and collaboration in bringing this Toolkit to fruition. Introduction INTRODUCTION By Pam Elam, Monumental Women President It's not often that you have the chance to be part of something truly historic. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work. -

Extended to March 11, 1966

PRESS RELEASES - JANUARY, FEBHUARY, MRCH, APRIL - 1966 Page APPLICATION Re-opening of Season Help Applications - 1 extended to March 11, 1966 AU GOGO - First event of season at Mall - Sat., April 23, BUDGETS - Park Commissioner Hovings remarks at Capital Budget hearings 2/16/66 Park Commissioner Hovings remarks about closing of Heckscher Playground, Children's Zoo and Carl Schurz Park if P.D. does not get fair share of city's Expense Budget this year. BROADWAY SHOW LEAGUE Opening Day (nothing done—not our release) CHESS TOURNAMENT - Entry blanks for boys and girls 17 yrs and under at 6 62nd St. and Central Park. Chess Program sponsored by Amer. Chess Foundation 6 A CURATORS Prospect Park and Central Park appointed by Comm. 7 and Staff members. Five biogs. added DUTCH STREET ORGAN - 4 Dutch organizations in New York cooperated in 8 bringing organ to Central Park. EASTER CANDY HUNTS - Sponsored by Quaker City Chocolate and Confectionery 9 Company at various locations in 5 boros, April 13. EGG ROLLING Contest - sponsored by Arnold Constable-Fifth Ave, 10 Saturday afternoon, April 9. Douglaston Park Golf Course, Wed., April 13 - Prizes 11 donated by Douglaston Steak House, GOLF Pelham Bay Park Golf Driving Range, Pelham Bay Park 12 facility open starting Sat., April 2, 1966. Courses open for seaon on Saturday, April 2, 1966, at 13 6 a.m., Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Richmond GOLDEN AGE Joe and Alice Nash, dancers. J. Hood Wright Golden Age 14 Center to entertain with 20 dancers at the Hebrew Home for the aged, on Fri. 1/18/66 Winter Carnival - Sat., Jan. -

The Alcoholic Q&A with Author Jonathan Ames and Artist Dean Haspiel

The Alcoholic Q&A with author Jonathan Ames and artist Dean Haspiel Q. Jonathan, you’ve written for TV, including an HBO pilot you’re filming this fall called Bored To Death; newspapers, including a column for the NY Press; and are the author of numerous books of essays and fiction including, What’s Not To Love? and Wake Up Sir! Now, a graphic novel? How did this happen? Ames: It happened because my good friend Dean Haspiel kept suggesting that we collaborate. I've always been a fan of Charles Bukowski and had seen some stories of his which were accompanied by illustrations from R. Crumb, so the idea of doing something similar with Dean appealed to me. Then Dean illustrated Harvey Pekar's The Quitter for Vertigo/DC and one day he brought me in to meet his editor for lunch and I don't know what we ate, but over the course of the meal, I suddenly had this idea for a comic about an alcoholic, called The Alcoholic; in my mind, it would be a perils-of-Pauline sort of tale—the alcoholic always in danger and getting into trouble, and this idea further blossomed and became the book . Q. Jonathan, the protagonist, Jonathan A. looks a lot like you, but the work is fictional. How much of the character really is you? Ames: Well, we share a lot of the same emotional DNA and we've had some similar experiences, but we are quite different in many ways and so he's his own strange person. -

Bored to Death "The Case of Pomeranian Guilt" by Eli Edelson Spec Script Eli Edelson 914-310-8844 E [email protected]

Bored to Death "The Case of Pomeranian Guilt" By Eli Edelson Spec Script Eli Edelson 914-310-8844 [email protected] © Copyright. Eli Edelson 2015 1 EXT. CENTRAL PARK, ROAD BY SHEEP MEADOW - DAY JONATHAN AMES, 30s, short and intellectual with hipster hair, runs furiously after a pudgy investment banker guy, DANIEL UZBECKERMAN, carrying a Pomeranian dog in a satchel. JONATHAN Drop the pooch Uzbeckerman! UZBECKERMAN Go fuck yourself weirdo! They dodge between droves of MOMS and DADS running with BABY STROLLERS. The dog obnoxiously yelps with fear. JONATHAN Drop your girlfriend’s dog! UZBECKERMAN Or what?! My net worth is over fifteen million, you can’t touch me! Both of them start to get sweaty and slow, clearly not runners. JONATHAN Just buy your own dog then. UZBECKERMAN Diocletian is my dog! They near a busy central park street/path. Uzbeckerman runs through one of those summer Sunday rollerblading parties with a DJ. Jonathan struggles to follow and collides with a gigantic shirtless gay man on roller-blades, goes down hard. Uzbeckerman suddenly slips on a pile of horseshit and the dog goes flying from the satchel. It lands right in front of an incoming horse carriage, the driver doesn’t see the tiny creature. CLOSE ON the Pomeranian’s pained, existential expression. This was my destiny? This is how it ends? It’s just too horrible. We CUT AWAY as the carriage fails to stop. Screams of horror ensue... FADE OUT. TEXT INSERT: 2 DAYS LATER 2. 2 INT. GEORGE ON JANE RESTAURANT BATHROOM - AFTERNOON Ames stands in a cramped stall with a faux-cigarette pipe between his fingers, pressed up against his two closest compatriots: RAY HUESTON, robust but short, absurd and bearded, and GEORGE CHRISTOPHER, a tall silver fox a la George Plimpton. -

Seeing Central Park Again for the First Time by Bike

Seeing Central Park Again For the First Time By Bike When I, Shawn Barton, moved to the Miami Area 10 years back, I thought I had already seen NYC’s attractions and explored my former “backyard” quite thoroughly. But I had never gone on a bike tour of Central Park. Biking in Central Park (Image: Flickr/Dave Winner, Last spring, I returned to Brooklyn to visit friends and relatives and see my old home again; and I went with an old friend on a bike tour in Central Park. I never knew how much I had missed. It was like seeing the park again for the first time. To learn more about how to book your own Central Park bike tour, visit bikerentalscentralpark.com – tours of the park for great price points. Read on to learn about what a bike tour has to offer! My Central Park Bike Tour It was simple, fast, and affordable to rent our bikes, along with helmets, locks, and all accompanying equipment. And just peddling over the grassy, rolling hills and past the blooming cherry blossom trees was exhilarating. The gorgeous nature with skyscrapers looming in the background is a truly unique sight. The Strawberry Fields (Image: nycgovparks.org) One of the first stops we made was at The Strawberry Fields, where we both appreciated this rustic preserve of the original park’s looks and the Beatles John Lennon to whom these acres are dedicated. But this was only one among numerous stops full of natural beauty. We stopped to stroll at Central Park Mall where we got panoramic views and a chance to watch artists and singers perform.