Phycitodes Albatella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Predispersal Seed Predation of Wyethia Amplexicaule, Crepis Acuminata, and Agoseris Glauca

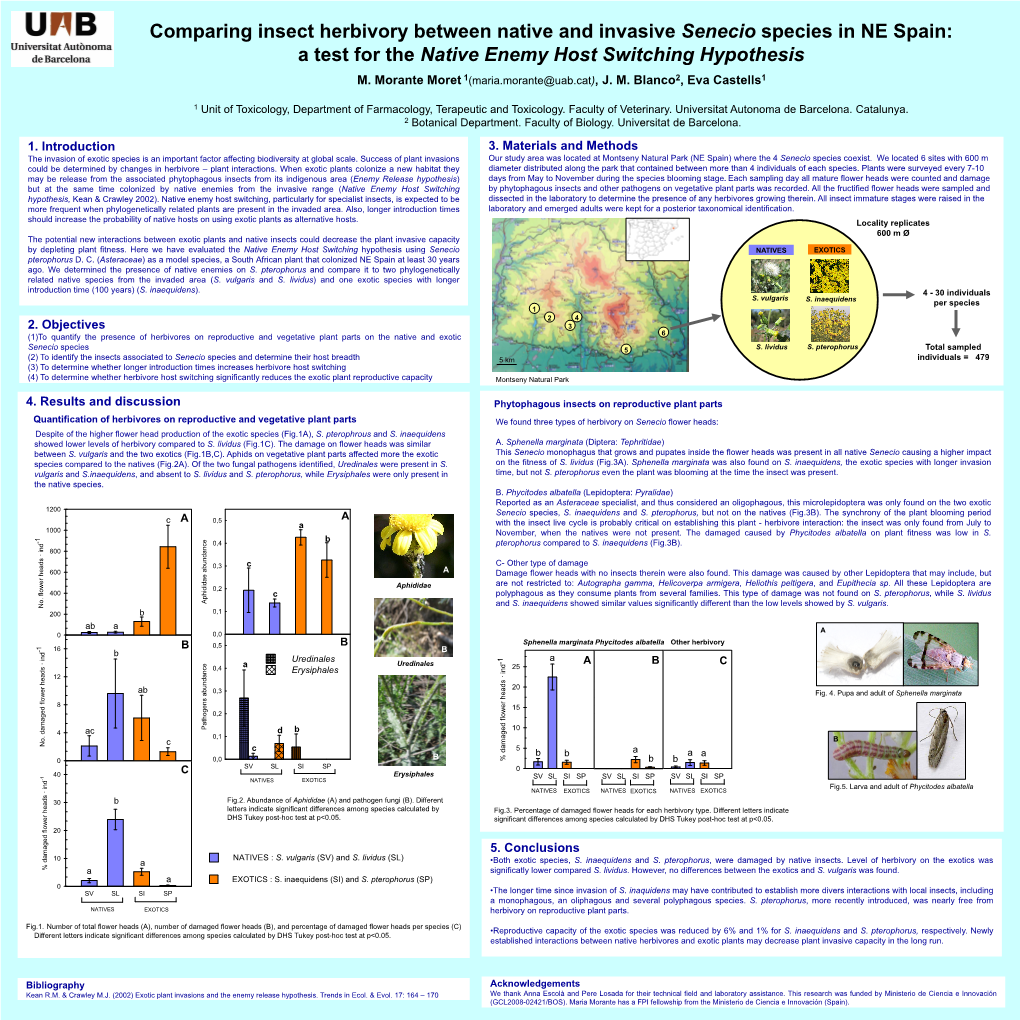

Predispersal seed predation of Wyethia amplexicaule, Crepis acuminata, and Agoseris glauca Robert L. Johnson and Val Jo Anderson Brigham Young University project • Document seed predation in select forb species • Document occurrence of pest parasitoids • Effect of treatment with imidacloprid methods • 3 plant populations • 20 plants – nearest plant to point on transect bisecting population • 5 random plants per imidacloprid treatment – soil drench – spray – control • Seed heads harvested following anthesis and reared in the lab • Following insect emergence, individual seed were examined for damage Imidacloprid treatment Soil drench: 0.5 gallons solution = 1.2 grams active ingredient Spray: foliar spray until solution begins dripping from foliage Wyethia amplexicaulis Reared capitula 2,256 Neotephritis finalis 2256 Trupanea nigricornis 186 Melanagromyza sp. 15 Lepidoptera 24 Seed damage 60 40 # samples 20 average=39.0% 0 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% % seed damage 50% 55% 60% 65% 70% 75% 80% 85% 90% 95% More Agoseris glauca Reared capitula 575 Campiglossa sp. 155 Diptera (unknown) 18 Seed damage 600 500 400 average=8.1 300 # samples 200 100 0 0% 1-20% 21-40% 41-60% 61-80% 81-99% More % seed damage Imidacloprid treatment: site x treatment (p<0.01) 18.0% b 16.0% 14.0% 12.0% 10.0% 8.0% a a 6.0% a percent seed damage 4.0% a a 2.0% a a a 0.0% Manti Ridge Teat Mountain Willow Creek habitat control spray drench Crepis acuminata Reared capitula: 2859 Campiglossa sp 52 Phycitodes albatella 133 subsp. mucidella Seed damage 220 200 180 160 -

Recerca I Territori V12 B (002)(1).Pdf

Butterfly and moths in l’Empordà and their response to global change Recerca i territori Volume 12 NUMBER 12 / SEPTEMBER 2020 Edition Graphic design Càtedra d’Ecosistemes Litorals Mediterranis Mostra Comunicació Parc Natural del Montgrí, les Illes Medes i el Baix Ter Museu de la Mediterrània Printing Gràfiques Agustí Coordinadors of the volume Constantí Stefanescu, Tristan Lafranchis ISSN: 2013-5939 Dipòsit legal: GI 896-2020 “Recerca i Territori” Collection Coordinator Printed on recycled paper Cyclus print Xavier Quintana With the support of: Summary Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Xavier Quintana Butterflies of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ................................................................................................................. 11 Tristan Lafranchis Moths of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ............................................................................................................................31 Tristan Lafranchis The dispersion of Lepidoptera in the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ...........................................................51 Tristan Lafranchis Three decades of butterfly monitoring at El Cortalet ...................................................................................69 (Aiguamolls de l’Empordà Natural Park) Constantí Stefanescu Effects of abandonment and restoration in Mediterranean meadows .......................................87 -

Gut Content Metabarcoding Unveils the Diet of a Flower‐Associated Coastal

ECOSPHERE NATURALIST No guts, no glory: Gut content metabarcoding unveils the diet of a flower-associated coastal sage scrub predator PAUL MASONICK , MADISON HERNANDEZ, AND CHRISTIANE WEIRAUCH Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, California 92521 USA Citation: Masonick, P., M. Hernandez, and C. Weirauch. 2019. No guts, no glory: Gut content metabarcoding unveils the diet of a flower-associated coastal sage scrub predator. Ecosphere 10(5):e02712. 10.1002/ecs2.2712 Abstract. Invertebrate generalist predators are ubiquitous and play a major role in food-web dynamics. Molecular gut content analysis (MGCA) has become a popular means to assess prey ranges and specificity of cryptic arthropods in the absence of direct observation. While this approach has been widely used to study predation on economically important taxa (i.e., pests) in agroecosystems, it is less frequently used to study the broader trophic interactions involving generalist predators in natural communities such as the diverse and threatened coastal sage scrub communities of Southern California. Here, we employ DNA metabarcoding-based MGCA and survey the taxonomically and ecologically diverse prey range of Phymata pacifica Evans, a generalist flower-associated ambush bug (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). We detected predation on a wide array of taxa including beneficial pollinators, potential pests, and other predatory arthropods. The success of this study demonstrates the utility of MGCA in natural ecosystems and can serve as a model for future diet investigations into other cryptic and underrepresented communities. Key words: biodiversity; blocking primers; DNA detectability half-life; Eriogonum fasciculatum; food webs; intraguild predation; natural enemies. Received 24 January 2019; accepted 11 February 2019. -

Insects and Fungi Associated with Carduus Thistles (Com Positae)

t I:iiW 12.5 I:iiW 1.0 W ~ 1.0 W ~ wW .2 J wW l. W 1- W II:"" W "II ""II.i W ft ~ :: ~ ........ 1.1 ....... j 11111.1 I II f .I I ,'"'' 1.25 ""11.4 111111.6 ""'1.25 111111.4 11111 /.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART I NATIONAL BlIREAU Of STANDARDS-1963-A NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS-1963-A I~~SECTS AND FUNGI ;\SSOCIATED WITH (~ARDUUS THISTLES (COMPOSITAE) r.-::;;;:;· UNITED STATES TECHNICAL PREPARED BY • DEPARTMENT OF BULLETIN SCIENCE AND G AGRICULTURE NUMBER 1616 EDUCATION ADMINISTRATION ABSTRACT Batra, S. W. T., J. R. Coulson, P. H. Dunn, and P. E. Boldt. 1981. Insects and fungi associated with Carduus thistles (Com positae). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Technical Bulletin No. 1616, 100 pp. Six Eurasian species of Carduus thistles (Compositae: Cynareael are troublesome weeds in North America. They are attacked by about 340 species of phytophagous insects, including 71 that are oligophagous on Cynareae. Of these Eurasian insects, 39 were ex tensively tested for host specificity, and 5 of them were sufficiently damf..ghg and stenophagous to warrant their release as biological control agents in North America. They include four beetles: Altica carduorum Guerin-Meneville, repeatedly released but not estab lished; Ceutorhynchus litura (F.), established in Canada and Montana on Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.; Rhinocyllus conicus (Froelich), widely established in the United States and Canada and beginning to reduce Carduus nutans L. populations; Trichosirocalus horridus ~Panzer), established on Carduus nutans in Virginia; and the fly Urophora stylata (F.), established on Cirsium in Canada. -

The Arthropoda Fauna of Corvo Island (Azores): New Records and Updated List of Species

VIERAEA Vol. 31 145-156 Santa Cruz de Tenerife, diciembre 2003 ISSN 0210-945X The Arthropoda fauna of Corvo island (Azores): new records and updated list of species VIRGÍLIO VIEIRA*, PAULO A. V. BORGES**, OLE KARSHOLT*** & JÖRG WUNDERLICH**** *Universidade dos Açores, Departamento de Biologia, CIRN, Rua da Mãe de Deus, PT - 9501-801 Ponta Delgada, Açores, Portugal [email protected] **Universidade dos Açores, Dep. de Ciências Agrárias, Terra-Chã, 9701 – 851 Angra do Heroísmo, Açores, Portugal [email protected] ***Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] ****Jörg Wunderlich, Hindenburgstr. 94, D-75334 Straubenhardt, Germany [email protected] VIEIRA, V., P.A.V. BORGES, O. KARSHOLT & J. WUNDERLICH (2003). La fauna de artrópodos de la isla de Corvo (Azores): lista actualizada de las especies incluyendo nuevos registros. VIERAEA 31: 145-156. RESUMEN: Se exponen los resultados de artrópodos (phylum Arthropoda) colectados y observados en la isla de Corvo, archipiélago de las Azores, durante los días 26.VII.1999 y 11-13.IX.2002. Con la inclusión de la literatura disponible, se citan 175 especies y subespecies (11.43% son endemismos comunes a las otras islas de las Azores), repartidas per 16 órdenes y 83 familias, de las que 32 son nuevas citas para la isla de Corvo. Phaneroptera nana Fieber (Orthoptera: Tettigonidae) se cita por primera vez para las Azores. Palabras clave: Arthropoda, isla de Corvo, Azores. ABSTRACT: The arthropod fauna (phylum Arthropoda) from the island of Corvo, Azores archipelago, was surveyed during four sampling days (26 July 1999; 11-13 September 2002). -

Newsletter Alaska Entomological Society

Newsletter of the Alaska Entomological Society Volume 10, Issue 1, May 2017 In this issue: DNA barcoding Alaska’s butterflies . 10 Notes on using LifeScanner for DNA-based iden- Upcoming Events . .1 tification of non-marine macroinvertebrates . 18 Western Flower Thrips and Alaska . .3 Highlights of the 10th annual meeting of the Orthosia hibisci (Guenée), the speckled green fruit- Alaska Entomological Society . 27 worm: confirmed causing extensive hardwood defoliation in Southcentral and Western Alaska5 Upcoming Events Figure 1: Graphic from Kluane Bioblitz flyer. Kluane BioBlitz, June 23–25, 2017 tional Park and Reserve. If you’d like more informa- tion, contact Bruce Bennett at [email protected]. Come join us for the Yukon’s BioBlitz in the Kluane re- Project website: http://www.inaturalist.org/projects/ gion. All are welcome to participate for the event which is kluane-bioblitz-2017-bioblitz-de-kluane-2017. part of Canada’s 150th anniversary celebrations. BioBlitz Canada and the Canadian Wildlife Federation are sup- porting a series of public BioBlitz’s across the nation and Eleventh Annual Meeting, January 2018 the Yukon Conservation Data Centre and Parks Canada in partnership with the Kluane First Nation and Cham- The eleventh annual meeting of the Alaska Entomologi- pagne and Aishihik First Nations are hosting the Yukon’s cal Society will take place in Anchorage in January 2018. 150BioBlitz in the Kluane area, including the Kluane Na- Check for updates on our events page as the meeting date approaches. Volume 10, Issue 1, May 2017 2 Western Flower Thrips and Alaska doi:10.7299/X7ST7Q01 of obligate diapause, and cryptic habit (Kirk and Terry, 2003). -

The Arthropoda Fauna of Corvo Island (Azores): New Records and Updated List of Species

VIERAEA Vol. 31 145-156 Santa Cruz de Tenerife, diciembre 2003 ISSN 0210-945X The Arthropoda fauna of Corvo island (Azores): new records and updated list of species VIRGÍLIO VIEIRA*, PAULO A. V. BORGES**, OLE KARSHOLT*** & JÖRG WUNDERLICH**** *Universidade dos Açores, Departamento de Biologia, CIRN, Rua da Mãe de Deus, PT - 9501-801 Ponta Delgada, Açores, Portugal [email protected] **Universidade dos Açores, Dep. de Ciências Agrárias, Terra-Chã, 9701 – 851 Angra do Heroísmo, Açores, Portugal [email protected] ***Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] ****Jörg Wunderlich, Hindenburgstr. 94, D-75334 Straubenhardt, Germany [email protected] VIEIRA, V., P.A.V. BORGES, O. KARSHOLT & J. WUNDERLICH (2003). La fauna de artrópodos de la isla de Corvo (Azores): lista actualizada de las especies incluyendo nuevos registros. VIERAEA 31: 145-156. RESUMEN: Se exponen los resultados de artrópodos (phylum Arthropoda) colectados y observados en la isla de Corvo, archipiélago de las Azores, durante los días 26.VII.1999 y 11-13.IX.2002. Con la inclusión de la literatura disponible, se citan 175 especies y subespecies (11.43% son endemismos comunes a las otras islas de las Azores), repartidas per 16 órdenes y 83 familias, de las que 32 son nuevas citas para la isla de Corvo. Phaneroptera nana Fieber (Orthoptera: Tettigonidae) se cita por primera vez para las Azores. Palabras clave: Arthropoda, isla de Corvo, Azores. ABSTRACT: The arthropod fauna (phylum Arthropoda) from the island of Corvo, Azores archipelago, was surveyed during four sampling days (26 July 1999; 11-13 September 2002). -

ADDITIONS to the FAUNISTICS of LEPIDOPTERA in the COMUNIDAD VALENCIANA (SPAIN) – P ART I Peter Huemer1 & Christian Wieser2

Boletín Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, n1 39 (2006) : 271−283. ADDITIONS TO THE FAUNISTICS OF LEPIDOPTERA IN THE COMUNIDAD VALENCIANA (SPAIN) – PART I Peter Huemer1 & Christian Wieser2 1 Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Naturwissenschaftliche Sammlungen, Feldstr. 11a, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria 2 Landesmuseum Kärnten, Museumgasse 2, A-9021 Klagenfurt, Austria Abstract: 475 species of Lepidoptera are recorded from Spain (provinces of Castellón, Valencia and Alicante), based on mate- rial collected in May 2004. The species inventory includes a new record for the European fauna, Coleophora sarehma Toll, 1956. Furthermore Elachista alicanta Kaila, 2005 was described from material based on this study. Key words: Lepidoptera, Coleophora sarehma, Elachista alicanta, faunistics, new records, Spain. Adiciones a la fauna de lepidópteros de la Comunidad Valenciana (España) – Primera parte Resumen: Se citan 467 especies de Lepidoptera de España (provincias de Castellón, Valencia y Alicante), sobre la base de material colectado en mayo de 2004. El inventario de especies incluye una nueva cita para la fauna europea, Coleophora sa- rehma Toll, 1956. Por otro lado, Elachista alicanta Kaila, 2005 se describió basándose en material de este trabajo. Palabras clave: Lepidoptera, Coleophora sarehma, Elachista alicanta, faunística, nuevas citas, España. Introduction The fauna of Lepidoptera in Spain is of a remarkable diver- & Blat Beltran, 1976; Font Bustos, 1978; Muñoz Juarez & sity within an European scale. It altogether includes 4263 Tormo Muñoz ,1985). Unfortunately some of the articles of species (Karsholt & Razowski, 1996) and is only overtop- this period were so poorly edited that have not received ped by France and Italy. Despite this enormous species- attention. Especially remarkable are some comprehensive richness, the tradition of faunistic surveys including all attempts on some areas of special natural interest (Calle, groups of Lepidoptera is rather limited. -

© Амурский Зоологический Журнал. IX(4), 2017. 188-204 © Amurian Zoological Journal. IX(4), 2017. 1

http://www.bgpu.ru/azj/ © Амурский зоологический журнал. IX(4), 2017. 188-204 http://elibrary.ru/title_about.asp?id=30906 © Amurian zoological journal. IX(4), 2017. 188-204 УДК 595.782 ОГНЕВКООБРАЗНЫЕ ЧЕШУЕКРЫЛЫЕ (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALOIDEA) АМУРСКОЙ ОБЛАСТИ А.Н. Стрельцов A PYRALID MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA: PYRALOIDEA) OF AMUR REGION A.N. Streltzov Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, Университетская наб. д. 7-9., Санкт-Петербург, 199034, Россия. E-mail: [email protected] Ключевые слова: огневкообразные чешуекрылые, Lepidoptera, Pyraloidea, фауна, Амурская область Резюме. Первая региональная сводка огневкообразным чешуекрылым (Lepidoptera, Pyraloidea). Для Амурской области указывается 284 вида огневкообразных чешуекрылых, относящиеся к 82 родам из 14 подсемейств 2 семейств. Учитывая степень изученности данного района можно предположить, что предлагаемый список близок к исчерпывающему. Проиводится полная библиография по огневкам региона. Saint Petersburg State University, 7/9 Universitetskaya emb., Saint Petersburg, 199034, Russia. E-mail: streltzov@ mail.ru Key words: pyralid moths, Lepidoptera, Pyraloidea, fauna, Amur region Summary. The first regional report of the pyralid moths (Lepidoptera, Pyraloidea). For the Amur region, 284 species of pyraloid moths are listed, belonging to 82 genera from 14 subfamilies of the 2 families. Given the degree of study of this area, it can be assumed that the proposed list is close to exhaustive. There is a complete bibliography on pyralid moths of this region. Огневкообразные чешуекрылые – Lepidop- тешествие на Амур совершил Р.К. Маак. От tera: Pyraloidea – крупная, широко распро- Нерчинска до устья Паньгухе экспедиция страненная группа бабочек с наибольшим двигалась на плоту, затем на одной из барж разнообразием в тропических широтах. В ус- второго муравьевского сплава проследова- ловиях Дальнего Востока России огневки со- ла до выхода Амура из Хинганского ущелья. -

An Annotated List of Insects and Other Arthropods

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An Annotated List of Insects and Other Arthropods Gary L Parsons Gerasimos Cassis Andrew R. Moldenke John D. Lattin Norman H. Anderson Jeffrey C. Miller Paul Hammond Timothy D. Schowalter U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon November 1991 Parson, Gary L.; Cassis, Gerasimos; Moldenke, Andrew R.; Lattin, John D.; Anderson, Norman H.; Miller, Jeffrey C; Hammond, Paul; Schowalter, Timothy D. 1991. Invertebrates of the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. V: An annotated list of insects and other arthropods. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-290. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 168 p. An annotated list of species of insects and other arthropods that have been col- lected and studies on the H.J. Andrews Experimental forest, western Cascade Range, Oregon. The list includes 459 families, 2,096 genera, and 3,402 species. All species have been authoritatively identified by more than 100 specialists. In- formation is included on habitat type, functional group, plant or animal host, relative abundances, collection information, and literature references where available. There is a brief discussion of the Andrews Forest as habitat for arthropods with photo- graphs of representative habitats within the Forest. Illustrations of selected ar- thropods are included as is a bibliography. Keywords: Invertebrates, insects, H.J. Andrews Experimental forest, arthropods, annotated list, forest ecosystem, old-growth forests. -

Phenological Groups of Snout Moths (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Crambidae) of Rostov-On-Don Area (Russia)

Phenological groups of snout moths (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Crambidae) of Rostov-on-Don area (Russia) A. N. Poltavsky Abstract. Results of pyralid moths caught into light-traps in the Rostov-on-Don area during 2006–2012 were analysed. Diagrams are presented of phenological group subdivisions made on the basis of quantitative data of pyralid imago activity from spring to autumn. Samenvatting. Felonogie van enkele groepen grasmotten (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Crambidae) in het Rostov-on-Don gebied (Rusland) De resultaten van mottenvangsten in lichtvallen in de streek van Rostov-on-Don gedurende 2006–2012 worden geanalyseerd. Diagrammen worden voorgesteld waarin fenologische groepen worden onderscheiden gebaseerd op kwantitatieve gegevens van de mottenactiviteit van lente tot herfst. Résumé. La phénologie de quelques pyralides (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae, Crambidae) dans la région de Rostov-on-Don (Russie) Les résultats des captures dans des pièges lumineux dans la région de Rostov-on-Don durant la période de 2006–2012 sont analysés. Des diagrammes sont présentés avec des groupes phénologiques basés sur des informations quantitatives des activités des Pyraloidea du printemps à l'automne. Key words: Rostov-on-Don area – pyralid moths – phonological groups – light-trapping. Poltavsky, Dr. A. N.: Botanical garden of Southern Federal University, Rostov-on-Don region. [email protected]. Material The climate of the Rostov area is characterized by a In the Rostov-on-Don area during 2006–2012 there short spring, hot summer, warm autumn and mild were caught 203 species of snout moths (Pyraloidea) by winter. These features are amplified in connection with light-trapping. Total amount of specimens – 87,767 ex., the global warming (Poltavsky et al.