Weak Prophecy: Recasting Prophetic Power in the Classical Hebrew Prophets and in Their Modern Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTES to the SEPTUAGINT EZEKIEL 6 Thematically Chapter 6

NOTES TO THE SEPTUAGINT EZEKIEL 6 Thematically chapter 6 continues chapters 4–5 with its threatening predictions. From a dramatized condemnation of Jerusalem the prophet turns now to address the mountains of the surrounding land of Israel, the sites of the high places with their idolatric worship. The Septuagint (LXX) is shorter than the Masoretic Text (MT). LXX lacks the conflations of MT and of its maximizing text into which vari- ants have been incorporated. On the other hand, the trimmer text of LXX sometimes suggests it has been contracted1. Whereas in MT verses 8-9 seem to ring a hopeful note, in LXX they further develop the threatening message of the forgoing verses. The Double Name Twice in a role in verse 3, and once in v. 11, the critical editions of LXX have single kúriov where MT reads the double Name evei inda. In earlier contributions we already dealt with this phenomenon2. Here it may suffice to briefly summarise the data, adding remarks on the treatment of the topic in some newer commen- taries, and on L.J. McGregor's evaluation of the Greek evidence. In MT the double Name evei inda occurs 301 times3. It is typical for the book of Ezekiel were it is attested 217 times. In these instances, the critical editions of the Hebrew text, BHK and BHS, characterise inîda∏ as a secondary intrusion, either by commanding the reader to delete (dl) it, or by saying that it is an addition (add). The basis for this correction is the Greek text, and the suggestion that inîda∏ was inserted into the text as a help for the reader, to remind him of the fact that the “tetragram” could not be pronounced and was to be replaced by Adonay. -

Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?

2 Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek? A Concise Compendium of the Many Internal and External Evidences of Aramaic Peshitta Primacy Publication Edition 1a, May 2008 Compiled by Raphael Christopher Lataster Edited by Ewan MacLeod Cover design by Stephen Meza © Copyright Raphael Christopher Lataster 2008 Foreword 3 Foreword A New and Powerful Tool in the Aramaic NT Primacy Movement Arises I wanted to set down a few words about my colleague and fellow Aramaicist Raphael Lataster, and his new book “Was the New Testament Really Written in Greek?” Having written two books on the subject myself, I can honestly say that there is no better free resource, both in terms of scope and level of detail, available on the Internet today. Much of the research that myself, Paul Younan and so many others have done is here, categorized conveniently by topic and issue. What Raphael though has also accomplished so expertly is to link these examples with a simple and unambiguous narrative style that leaves little doubt that the Peshitta Aramaic New Testament is in fact the original that Christians and Nazarene-Messianics have been searching for, for so long. The fact is, when Raphael decides to explore a topic, he is far from content in providing just a few examples and leaving the rest to the readers’ imagination. Instead, Raphael plumbs the depths of the Aramaic New Testament, and offers dozens of examples that speak to a particular type. Flip through the “split words” and “semi-split words” sections alone and you will see what I mean. -

Ezekiel Chapter 21

Ezekiel Chapter 21 Chapter 21: Since the people did not seem to understand the parable of the devouring fire, Ezekiel now explains the impending judgment in terms of a sword. First, the lord is pictured as a warrior who says, “I the Lord have drawn forth my sword out of his sheath” (verse 5). Then the sword is sharpened to make a sore slaughter (verse 10), and directed toward Judah (verse 20). Finally, Ammon would likewise be slain by the sword (verses 28-32). (Verse 21), gives interesting insight into the Babylonian practice of divination. Three distinct ways for determining the will of the gods are mentioned. Casting arrows (much like our “drawing straws”), consulting images (directly or as mediums to departed spirits), and hepatoscopy, or the examination of the liver. In the last named practice, a sacrificial animal was slain, its liver was examined, and the particular shape and configuration was compared with a catalog of symptoms and predictions. The point is that no matter how much the Babylonian king foolishly uses his divination, the will of the one true God will be accomplished. In verses (21:1-7) The Word came. This is the sign of the sword against Jerusalem. God depicts His judgment in terms of a man unsheathing his polished sword for a deadly thrust. God is the swordsman (verses 3-4), but Babylon is His sword (verse 19). Ezekiel 21:1-2 "And the word of the LORD came unto me, saying," "Son of man, set thy face toward Jerusalem, and drop [thy word] toward the holy places, and prophesy against the land of Israel," This is the beginning of another prophecy. -

A Biographical Study of Samuel

Scholars Crossing Old Testament Biographies A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible 10-2018 A Biographical Study of Samuel Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "A Biographical Study of Samuel" (2018). Old Testament Biographies. 25. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old Testament Biographies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Samuel CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY I. The pre-ministry of Samuel—A boy in the tabernacle A. Hannah was his mother. 1. Her prayer for her son a. Samuel was born as a result of God’s answering Hannah’s prayer and touching her barren womb (1 Sam. 1:2, 19, 20). b. He was promised to the Lord even before his birth (1 Sam. 1:10-12). c. He became the second of two famous Old Testament Nazarites. Samson was the first (Judg. 13:7, 13-14; 1 Sam. 1:11). 2. Her presentation of her son—After he was weaned, Hannah dedicated him in the tabernacle (1Sam. 1:23-28). B. Eli was his mentor. 1. He then was raised for God’s service by the old priest Eli in the tabernacle (1 Sam. 2:11, 18, 21). -

Around the Point

Around the Point Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman Around the Point: Studies in Jewish Literature and Culture in Multiple Languages, Edited by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman and Ber Kotlerman This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Hillel Weiss, Roman Katsman, Ber Kotlerman and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5577-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5577-8 CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... viii Around the Point .......................................................................................... 1 Hillel Weiss Medieval Languages and Literatures in Italy and Spain: Functions and Interactions in a Multilingual Society and the Role of Hebrew and Jewish Literatures ............................................................................... 17 Arie Schippers The Ashkenazim—East vs. West: An Invitation to a Mental-Stylistic Discussion of the Modern Hebrew Literature ........................................... -

SAINT MICHAEL the ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH

ARCHDIOCESE OF GALVESTON-HOUSTON SAINT MICHAEL the ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH JULY 11, 2021 | FIFTEENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jesus summoned the Twelve and began to send them out two by two and gave them authority over unclean spirits. Mark 6:7 1801 SAGE ROAD, HOUSTON, TEXAS 77056 | (713) 621-4370 | STMICHAELCHURCH.NET ST. MICHAEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH The Gospel This week’s Gospel and the one for next week describe how Jesus sent the disciples to minister in his name and the disciples’ return to Jesus afterward. These two passages, however, are not presented together in Mark’s Gospel. Inserted between the two is the report of Herod’s fears that Jesus is John the Baptist back from the dead. In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus’ ministry is presented in connection with the teaching of John the Baptist. Jesus’ public ministry begins after John is arrested. John the Baptist prepared the way for Jesus, who preached the fulfillment of the Kingdom of God. While we do not read these details about John the Baptist in our Gospel this week or next week, our Lectionary sequence stays consistent with Mark’s theme. Recall that last week we heard how Jesus was rejected in his hometown of Nazareth. The insertion of the reminder about John the Baptist’s ministry and his death at the hands of Herod in Mark’s Gospel makes a similar point. Mark reminds his readers about this dangerous context for Jesus’ ministry and that of his disciples. Preaching repentance and the Kingdom of God is dangerous business for Jesus and for his disciples. -

“As Those Who Are Taught” Symposium Series

“AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Symposium Series Christopher R. Matthews, Editor Number 27 “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL Edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Copyright © 2006 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data “As those who are taught” : the interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL / edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull. p. cm. — (Society of biblical literature symposium series ; no. 27) Includes indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-58983-103-2 (paper binding : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58983-103-9 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Isaiah—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—History. 2. Bible. O.T. Isaiah— Versions. 3. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. McGinnis, Claire Mathews. II. Tull, Patricia K. III. Series: Symposium series (Society of Biblical Literature) ; no. 27. BS1515.52.A82 2006 224'.10609—dc22 2005037099 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

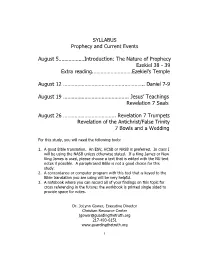

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

James 4:2 (NKJV… You Do Not Have Because You Do Not 6

5. Moses asks see ________________________. Exodus 33:18 (NKJV) And he said, "Please, show me Your glory." 21 Days of Prayer – Part 3 – The God Who Answers Sunday, August 20, 2017 James 4:2 (NKJV… you do not have because you do not 6. Hezekiah prays and _______________________. ask. 2 Kings 20:3 (NKJV) "Remember now, O LORD, I pray, how I have walked before You in truth and with a loyal heart, and have done what was good in Your sight." And Hezekiah wept bitterly. 1. Hannah prayed for a ________________________. 1 Samuel 1:11 (NKJV) Then she made a vow and said, "O LORD of hosts, if You will indeed look on the affliction of Your maidservant and remember me, and not forget Your maidservant, but will give Your maidservant a male child, then I will give him to the LORD all the days of his life, and no razor shall come upon 7. 7. Daniel prays for God to reveal a dream and its his head." interpretation and saves _______________________. Daniel 2:17-18 (NKJV) Then Daniel went to his house, and made the decision known to Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah, his companions, that they might seek mercies from the God of heaven concerning this secret, so that Daniel and 2. Peter released from ___________________________. his companions might not perish with the rest of the wise men of Babylon. Acts 12:5 (NKJV) Peter was therefore kept in prison, but constant prayer was offered to God for him by the church. 8. Elisha prays for his servants eyes to be opened to see __________________________________. -

Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John Kyle Ronchetto Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Classics Honors Projects Classics Department 2017 Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John Kyle Ronchetto Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Ronchetto, Kyle, "Manifestations of God: Theophanies in the Hebrew Prophets and the Revelation of John" (2017). Classics Honors Projects. 24. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/classics_honors/24 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANIFESTATIONS OF GOD: THEOPHANIES IN THE HEBREW PROPHETS AND THE REVELATION OF JOHN Kyle Ronchetto Advisor: Nanette Goldman Department: Classics March 30, 2017 Table of Contents Introduction........................................................................................................................1 Chapter I – God in the Hebrew Bible..............................................................................4 Introduction to Hebrew Biblical Literature...............................................................4 Ideas and Images of God..........................................................................................4 -

Notes on Zechariah 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Zechariah 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE AND WRITER The title of this book comes from its traditional writer, as is true of all the prophetical books of the Old Testament. The name "Zechariah" (lit. "Yahweh Remembers") was a common one among the Israelites, which identified at least 27 different individuals in the Old Testament, perhaps 30.1 It was an appropriate name for the writer of this book, because it explains that Yahweh remembers His chosen people, and His promises, and will be faithful to them. This Zechariah was the son of Berechiah, the son of Iddo (1:1, 7; cf. Ezra 5:1; 6:14; Neh. 12:4, 16). Zechariah, like Jeremiah and Ezekiel, was both a prophet and a priest. He was obviously familiar with priestly things (cf. ch. 3; 6:9-15; 9:8, 15; 14:16, 20, 21). Since he was a young man (Heb. na'ar) when he began prophesying (2:4), he was probably born in Babylonian captivity and returned to Palestine very early in life, in 536 B.C. with Zerubbabel and Joshua. Zechariah apparently survived Joshua, the high priest, since he became the head of his own division of priests in the days of Joiakim, the son of Joshua (Neh. 12:12, 16). Zechariah became a leading priest in the restoration community succeeding his grandfather (or ancestor), Iddo, who also returned from captivity in 536 B.C., as the leader of his priestly family (Neh. 12:4, 16). Zechariah's father, Berechiah (1:1, 7), evidently never became prominent. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord.