Unit 3: Logical Atomism: Bertrand Russell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Companion to Analytic Philosophy

A Companion to Analytic Philosophy Blackwell Companions to Philosophy This outstanding student reference series offers a comprehensive and authoritative survey of philosophy as a whole. Written by today’s leading philosophers, each volume provides lucid and engaging coverage of the key figures, terms, topics, and problems of the field. Taken together, the volumes provide the ideal basis for course use, represent- ing an unparalleled work of reference for students and specialists alike. Already published in the series 15. A Companion to Bioethics Edited by Helga Kuhse and Peter Singer 1. The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy Edited by Nicholas Bunnin and Eric 16. A Companion to the Philosophers Tsui-James Edited by Robert L. Arrington 2. A Companion to Ethics Edited by Peter Singer 17. A Companion to Business Ethics Edited by Robert E. Frederick 3. A Companion to Aesthetics Edited by David Cooper 18. A Companion to the Philosophy of 4. A Companion to Epistemology Science Edited by Jonathan Dancy and Ernest Sosa Edited by W. H. Newton-Smith 5. A Companion to Contemporary Political 19. A Companion to Environmental Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit Edited by Dale Jamieson 6. A Companion to Philosophy of Mind 20. A Companion to Analytic Philosophy Edited by Samuel Guttenplan Edited by A. P. Martinich and David Sosa 7. A Companion to Metaphysics Edited by Jaegwon Kim and Ernest Sosa Forthcoming 8. A Companion to Philosophy of Law and A Companion to Genethics Legal Theory Edited by John Harris and Justine Burley Edited by Dennis Patterson 9. A Companion to Philosophy of Religion A Companion to African-American Edited by Philip L. -

" CONTENTS of VOLUME XXXVIII—1964 >•

" CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVIII—1964 >• it ARTICLES: pAGE Anderson, James F., Was St. Thomas a Philosopher? 435 Boh, Ivan, An Examination of Some Proofs in Burleigh's Propo- sitional Logic 44 Brady, Jules M., St. Augustine's Theory of Seminal Reasons.. 141 Burns, J. Patout, Action in Suarez 453 Burrell, David B., Kant and Philosophical Knowledge 189 Chroust, Anton-Hermann, Some Reflections on the Origin of the Term " Philosopher " 423 Collins, James, The Work of Rudolf Allers 28 Fairbanks, Matthew J., C. S. Peirce and Logical Atomism 178 Grisez, Germain G., Sketch of a Future Metaphysics 310 O'Brien, Andrew J., Duns Scotus' Teaching on the Distinction between Essence and Existence 61 McWilliams, James A., The Concept as Villain 445 Pax, Clyde V., Philosophical Reflection: Gabriel Marcel 159 Smith, John E., The Relation of Thought and Being: Some Lessons from Hegel's Encyclopedia 22 Stokes, Walter E., Whitehead's Challenge to Theistic Realism. ... 1 Tallon, Andrew, Personal Immortality in Averroes' Tahafut Al- Tahafut 341 REVIEW ARTICLE : O'Neil, Charles J., Another Notable Study of Aristotle's Meta physics 509 ill iv Contents of Volume XXXVIII DEPARTMENTS : PAGE Book Brevities 551 Books Received 133, 274, 415, 557 Chronicles: The Husserl Archives and the Edition of Husserl's Works 473 International Congresses of Philosophy in Mexico City.. 278 Progress Report: Philosophy in the NCE 214 The Secretary's Chronicle 80, 218, 358, 483 BOOK REVIEWS: Anderson, James P., Natural Theology: The Metaphysics of God 265 Austin, J. L., Philosophical Papers 125 Capek, Milec, The Philosophical Impact of Contemporary Physics 248 Caturelli, Alberto, La fdosofiu en Argentina actual 403 Crocker, Lester G., Nature and Cidture: Ethical Thought in the French Englightement 539 Dufrenne, Mikel, Language and Philosophy, transl. -

Reference and Sense

REFERENCE AND SENSE y two distinct ways of talking about the meaning of words y tlkitalking of SENSE=deali ng with relationshippggs inside language y talking of REFERENCE=dealing with reltilations hips bbtetween l. and the world y by means of reference a speaker indicates which things (including persons) are being talked about ege.g. My son is in the beech tree. II identifies persons identifies things y REFERENCE-relationship between the Enggplish expression ‘this p pgage’ and the thing you can hold between your finger and thumb (part of the world) y your left ear is the REFERENT of the phrase ‘your left ear’ while REFERENCE is the relationship between parts of a l. and things outside the l. y The same expression can be used to refer to different things- there are as many potential referents for the phrase ‘your left ear’ as there are pppeople in the world with left ears Many expressions can have VARIABLE REFERENCE y There are cases of expressions which in normal everyday conversation never refer to different things, i.e. which in most everyday situations that one can envisage have CONSTANT REFERENCE. y However, there is very little constancy of reference in l. Almost all of the fixing of reference comes from the context in which expressions are used. y Two different expressions can have the same referent class ica l example: ‘the MiMorning St’Star’ and ‘the Evening Star’ to refer to the planet Venus y SENSE of an expression is its place in a system of semantic relati onshi ps wit h other expressions in the l. -

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics YEUNG, \y,ang -C-hun ...:' . '",~ ... ~ .. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy In Philosophy The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2010 Abstract of thesis entitled: Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics Submitted by YEUNG, Wang Chun for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in July 2009 This ,thesis investigates problems surrounding the lively debate about how Kripke's examples of necessary a posteriori truths and contingent a priori truths should be explained. Two-dimensionalism is a recent development that offers a non-reductive analysis of such truths. The semantic interpretation of two-dimensionalism, proposed by Jackson and Chalmers, has certain 'descriptive' elements, which can be articulated in terms of the following three claims: (a) names and natural kind terms are reference-fixed by some associated properties, (b) these properties are known a priori by every competent speaker, and (c) these properties reflect the cognitive significance of sentences containing such terms. In this thesis, I argue against two arguments directed at such 'descriptive' elements, namely, The Argument from Ignorance and Error ('AlE'), and The Argument from Variability ('AV'). I thereby suggest that reference-fixing properties belong to the semantics of names and natural kind terms, and not to their metasemantics. Chapter 1 is a survey of some central notions related to the debate between descriptivism and direct reference theory, e.g. sense, reference, and rigidity. Chapter 2 outlines the two-dimensional approach and introduces the va~ieties of interpretations 11 of the two-dimensional framework. -

Puzzles About Descriptive Names Edward Kanterian

Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian To cite this version: Edward Kanterian. Puzzles about descriptive names. Linguistics and Philosophy, Springer Verlag, 2010, 32 (4), pp.409-428. 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1. hal-00566732 HAL Id: hal-00566732 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00566732 Submitted on 17 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Linguist and Philos (2009) 32:409–428 DOI 10.1007/s10988-010-9066-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Puzzles about descriptive names Edward Kanterian Published online: 17 February 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract This article explores Gareth Evans’s idea that there are such things as descriptive names, i.e. referring expressions introduced by a definite description which have, unlike ordinary names, a descriptive content. Several ignored semantic and modal aspects of this idea are spelled out, including a hitherto little explored notion of rigidity, super-rigidity. The claim that descriptive names are (rigidified) descriptions, or abbreviations thereof, is rejected. It is then shown that Evans’s theory leads to certain puzzles concerning the referential status of descriptive names and the evaluation of identity statements containing them. -

The End of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico

Living in Silence: the End of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and Lecture on Ethics Johanna Schakenraad Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus logico-philosophicus starts as a book on logic and (the limits of) language. In the first years after publication (in 1921) it was primarily read as a work aiming to put an end to nonsensical language and all kinds of metaphysical speculation. For this reason it had a great influence on the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle. But for Wittgenstein himself it had another and more important purpose. In 1919 he had sent his manuscript to Ludwig von Ficker, the publisher of the literary journal der Brenner, hoping that Ficker would consider publishing the Tractatus. In the accompanying letter he explains how he wishes his book to be understood. He thinks it is necessary to give an explanation of his book because the content might seem strange to Ficker, but, he writes: In reality, it isn’t strange to you, for the point of the book is ethical. I once wanted to give a few words in the foreword which now actually are not in it, which, however, I’ll write to you now because they might be a key to you: I wanted to write that my work consists of two parts: of the one which is here, and of everything which I have not written. And precisely this second part is the important one. For the Ethical is delimited from within, as it were, by my book; and I’m convinced that, strictly speaking, it can ONLY be delimited in this way. -

1 Reference 1. the Phenomenon Of

1 Reference 1. The phenomenon of reference In a paper evaluating animal communication systems, Hockett and Altmann (1968) presented a list of what they found to be the distinctive characteristics which, collectively, define what it is to be a human language. Among the characteristics is the phenomenon of "aboutness", that is, in using a human language we talk about things that are external to ourselves. This not only includes things that we find in our immediate environment, but also things that are displaced in time and space. For example, at this moment I can just as easily talk about Tahiti or the planet Pluto, neither of which are in my immediate environment nor ever have been, as I can about this telephone before me or the computer I am using at this moment. Temporal displacement is similar: it would seem I can as easily talk about Abraham Lincoln or Julius Caesar, neither a contemporary of mine, as I can of former president Bill Clinton, or my good friend John, who are contemporaries of mine. This notion of aboutness is, intuitively, lacking in some contrasting instances. For example, it is easy to think that animal communication systems lack this characteristic—that the mating call of the male cardinal may be caused by a certain biological urge, and may serve as a signal that attracts mates, but the call itself is (putatively) not about either of those things. Or, consider an example from human behavior. I hit my thumb with a hammer while attempting to drive in a nail. I say, "Ouch!" In so doing I am saying this because of the pain, and I am communicating to anyone within earshot that I am in pain, but the word ouch itself is not about the pain I feel. -

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

Russell's Theory of Descriptions

Russell’s theory of descriptions PHIL 83104 September 5, 2011 1. Denoting phrases and names ...........................................................................................1 2. Russell’s theory of denoting phrases ................................................................................3 2.1. Propositions and propositional functions 2.2. Indefinite descriptions 2.3. Definite descriptions 3. The three puzzles of ‘On denoting’ ..................................................................................7 3.1. The substitution of identicals 3.2. The law of the excluded middle 3.3. The problem of negative existentials 4. Objections to Russell’s theory .......................................................................................11 4.1. Incomplete definite descriptions 4.2. Referential uses of definite descriptions 4.3. Other uses of ‘the’: generics 4.4. The contrast between descriptions and names [The main reading I gave you was Russell’s 1919 paper, “Descriptions,” which is in some ways clearer than his classic exposition of the theory of descriptions, which was in his 1905 paper “On Denoting.” The latter is one of the optional readings on the web site, and I reference it below sometimes as well.] 1. DENOTING PHRASES AND NAMES Russell defines the class of denoting phrases as follows: “By ‘denoting phrase’ I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present king of England, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth around the sun, the revolution of the sun around the earth. Thus a phrase is denoting solely in virtue of its form.” (‘On Denoting’, 479) Russell’s aim in this article is to explain how expressions like this work — what they contribute to the meanings of sentences containing them. -

Generalized Molecular Formulas in Logical Atomism

Journal for the History of Analytical Philosophy An Argument for Completely General Facts: Volume 9, Number 7 Generalized Molecular Formulas in Logical Editor in Chief Atomism Audrey Yap, University of Victoria Landon D. C. Elkind Editorial Board Annalisa Coliva, UC Irvine In his 1918 logical atomism lectures, Russell argued that there are Vera Flocke, Indiana University, Bloomington no molecular facts. But he posed a problem for anyone wanting Henry Jackman, York University to avoid molecular facts: we need truth-makers for generaliza- Frederique Janssen-Lauret, University of Manchester tions of molecular formulas, but such truth-makers seem to be Kevin C. Klement, University of Massachusetts both unavoidable and to have an abominably molecular charac- Consuelo Preti, The College of New Jersey ter. Call this the problem of generalized molecular formulas. I clarify Marcus Rossberg, University of Connecticut the problem here by distinguishing two kinds of generalized Anthony Skelton, Western University molecular formula: incompletely generalized molecular formulas Mark Textor, King’s College London and completely generalized molecular formulas. I next argue that, if empty worlds are logically possible, then the model-theoretic Editors for Special Issues and truth-functional considerations that are usually given ad- Sandra Lapointe, McMaster University dress the problem posed by the first kind of formula, but not the Alexander Klein, McMaster University problem posed by the second kind. I then show that Russell’s Review Editors commitments in 1918 provide an answer to the problem of com- Sean Morris, Metropolitan State University of Denver pletely generalized molecular formulas: some truth-makers will Sanford Shieh, Wesleyan University be non-atomic facts that have no constituents. -

Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950

Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication Volume 4 200 YEARS OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY Article 5 2008 Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950 Mathieu Marion Université du Quéebec à Montréal, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/biyclc This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Marion, Mathieu (2008) "Theory Of Knowledge In Britain From 1860 To 1950," Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication: Vol. 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 This Proceeding of the Symposium for Cognition, Logic and Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory of Knowledge in Britain from 1860 to 1950 2 The Baltic International Yearbook of better understood as an attempt at foisting on it readers a particular Cognition, Logic and Communication set of misconceptions. To see this, one needs only to consider the title, which is plainly misleading. The Oxford English Dictionary gives as one August 2009 Volume 4: 200 Years of Analytical Philosophy of the possible meanings of the word ‘revolution’: pages 1-34 DOI: 10.4148/biyclc.v4i0.129 The complete overthrow of an established government or social order by those previously subject to it; an instance of MATHIEU MARION this; a forcible substitution of a new form of government. -

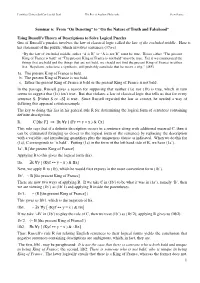

Using Russell's Theory of Descriptions to S

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú The Rise of Analytic Philosophy Scott Soames Seminar 6: From “On Denoting” to “On the Nature of Truth and Falsehood” Using Russell’s Theory of Descriptions to Solve Logical Puzzles One of Russell’s puzzles involves the law of classical logic called the law of the excluded middle. Here is his statement of the puzzle, which involves sentences (37a-c). “By the law of excluded middle, either “A is B” or “A is not B” must be true. Hence either “The present King of France is bald” or “The present King of France is not bald” must be true. Yet if we enumerated the things that are bald and the things that are not bald, we should not find the present King of France in either list. Hegelians, who love a synthesis, will probably conclude that he wears a wig.” (485) 1a. The present King of France is bald. b. The present King of France is not bald. c. Either the present King of France is bald or the present King of France is not bald. In the passage, Russell gives a reason for supposing that neither (1a) nor (1b) is true, which in turn seems to suggest that (1c) isn’t true. But that violates a law of classical logic that tells us that for every sentence S, ⎡Either S or ~S⎤ is true. Since Russell regarded the law as correct, he needed a way of defusing this apparent counterexample. The key to doing this lies in his general rule R for determining the logical form of sentences containing definite descriptions.