Term Limits and Tax Cuts, 1999-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

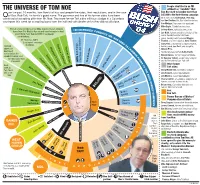

The Universe of Tom

People identified in an FBI THE UNIVERSE OF TOM NOE ■ affidavit as “conduits” that ver the past 10 months, Tom Noe’s fall has cost people their jobs, their reputations, and in the case Tom Noe used to launder more than Oof Gov. Bob Taft, his family’s good name. The governor and two of his former aides have been $45,000 to the Bush-Cheney campaign: convicted of accepting gifts from Mr. Noe. Two more former Taft aides will face a judge in a Columbus MTS executives Bart Kulish, Phil Swy, courtroom this week for accepting loans from the indicted coin dealer which they did not disclose. and Joe Restivo, Mr. Noe’s brother-in-law. Sue Metzger, Noe executive assistant. Mike Boyle, Toledo businessman. Five of seven members of the Ohio Supreme Court stepped FBI-IDENTIF Jeffrey Mann, Toledo businessman. down from The Blade’s Noe records case because he had IED ‘C OND Joe Kidd, former executive director of the given them more than $20,000 in campaign UIT S’ M Lucas County board of elections. contributions. R. N Lucas County Commissioner Maggie OE Mr. Noe was Judith U Thurber, and her husband, Sam Thurber. Lanzinger’s campaign SE Terrence O’Donnell D Sally Perz, a former Ohio representative, chairman. T Learned Thomas Moyer O her husband, Joe Perz, and daughter, Maureen O’Connor L about coin A U Allison Perz. deal about N D Toledo City Councilman Betty Shultz. a year before the E Evelyn Stratton R Donna Owens, former mayor of Toledo. scandal erupted; said F Judith Lanzinger U H. -

Frontier Knowledge Basketball the Map to Ohio's High-Tech Future Must Be Carefully Drawn

Beacon Journal | 12/29/2003 | Fronti... Page 1 News | Sports | Business | Entertainment | Living | City Guide | Classifieds Shopping & Services Search Articles-last 7 days for Go Find a Job Back to Home > Beacon Journal > Wednesday, Dec 31, 2003 Find a Car Local & State Find a Home Medina Editorial Ohio Find an Apartment Portage Classifieds Ads Posted on Mon, Dec. 29, Stark 2003 Shop Nearby Summit Wayne Sports Baseball Frontier knowledge Basketball The map to Ohio's high-tech future must be carefully drawn. A report INVEST YOUR TIME Colleges WISELY Football questions directions in the Third Frontier Project High School Keep up with local business news and Business information, Market Arts & Living Although voters last month rejected floating bonds to expand the updates, and more! Health state's high-tech job development program, the Third Frontier Project Food The latest remains on track to spend more than $100 million a year over the Enjoy in business Your Home next decade. The money represents a crucial investment as Ohio news Religion weathers a painful economic transition. A new report wisely Premier emphasizes the existing money must be spent with clear and realistic Travel expectations and precise accountability. Entertainment Movies Music The report, by Cleveland-based Policy Matters Ohio, focuses only on Television the Third Frontier Action Fund, a small but long-running element of Theater the Third Frontier Project. The fund is expected to disburse $150 US & World Editorial million to companies, universities and non-profit research Voice of the People organizations. Columnists Obituaries It has been up and running since 1998, under the administration of Corrections George Voinovich. -

OHIO HISTORY Etablished in June 1887 As the Ohio Archaeological Volume 113 / Winter-Spring 2004 and Historical Quarterly

OHIO HISTORY Etablished in June 1887 as the Ohio Archaeological Volume 113 / Winter-Spring 2004 and Historical Quarterly www.ohiohistory.org/publications/ohiohistory EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Contents Randall Buchman Defiance College ARTICLES Andrew R. L. Cayton Communication Technology Transforms the Marketplace: 4 Miami University The Effect of the Telegraph, Telephone, and Ticker on the John J. Grabowski Cincinnati Merchants’ Exchange Case Western Reserve by Bradford W. Scharlott University and Western Reserve Historical Society Steubenville, Ohio, and the Nineteenth-Century 18 Steamboat Trade R. Douglas Hurt Iowa State University by Jerry E. Green George W. Knepper University of Akron BOOK REVIEWS Robert M. Mennel University of New Hampshire The Collected Works of William Howard Taft 31 Vol. 5, Popular Government & The Anti-trust Act and the Supreme Zane Miller Court. Edited with commentary by David Potash and Donald F. University of Cincinnati Anderson; Marian J. Morton Vol. 6, The President and His Powers & The United States and John Carroll University Peace. Edited with commentary by W. Carey McWilliams and Frank X. Gerrity. Larry L. Nelson —REVIEWED BY CLARENCE E. WUNDERLIN JR. Ohio Historical Society, Fort Meigs From Blackjacks To Briefcases: A History of Commercialized 32 Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States. By Robert Harry Scheiber Michael Smith. —REVIEWED BY JAMES E. CEBULA. University of California, Berkeley Confronting American Labor: The New Left Dilemma. By Jeffrey W. 33 Coker. —REVIEWED BY TERRY A. COONEY. Warren Van Tine The Ohio State University European Capital, British Iron, and an American Dream: The Story 34 of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad. By William Reynolds; Mary Young edited by Peter K. -

This Year's Presidential Prop8id! CONTENTS

It's What's Inside That Counts RIPON MARCH, 1973 Vol. IX No.5 ONE DOLLAR This Year's Presidential Prop8ID! CONTENTS Politics: People .. 18 Commentary Duly Noted: Politics ... 25 Free Speech and the Pentagon ... .. .. 4 Duly Noted: Books ................ ......... 28 Editorial Board Member James. Manahan :e Six Presidents, Too Many Wars; God Save This views the past wisdom of Sen. RIchard M .. NIX Honorable Court: The Supreme Court Crisis; on as it affects the cases of A. Ernest FItzge The Creative Interface: Private Enterprise and rald and Gordon Ru1e, both of whom are fired the Urban Crisis; The Running of Richard Nix Pentagon employees. on; So Help Me God; The Police and The Com munity; Men Behind Bars; Do the Poor Want to Work? A Social Psychological Study of The Case for Libertarianism 6 Work Orientations; and The Bosses. Mark Frazier contributing editor of Reason magazine and New England coordinator for the Libertarian Party, explains why libe:allsm .and Letters conservatism are passe and why libertanan 30 ism is where it is at. 14a Eliot Street 31 Getting College Republicans Out of the Closet 8 Last month, the FORUM printed the first in a series of articles about what the GOP shou1d be doing to broaden its base. Former RNC staff- er J. Brian Smith criticized the Young Voters Book Review for the President for ignoring college students. YVP national college director George Gordon has a few comments about what YVP did on The Politics of Principle ................ 22 campus and what the GOP ought to be doing John McCIaughry, the one-time obscure Ver in the future. -

Blackout 2003: How Did It Happen and Why? Hearings Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives

BLACKOUT 2003: HOW DID IT HAPPEN AND WHY? HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 3 and SEPTEMBER 4, 2003 Serial No. 108–54 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 89–467PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 12:14 Jan 26, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 89467.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE W.J. ‘‘BILLY’’ TAUZIN, Louisiana, Chairman MICHAEL BILIRAKIS, Florida JOHN D. DINGELL, Michigan JOE BARTON, Texas Ranking Member FRED UPTON, Michigan HENRY A. WAXMAN, California CLIFF STEARNS, Florida EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio RALPH M. HALL, Texas JAMES C. GREENWOOD, Pennsylvania RICK BOUCHER, Virginia CHRISTOPHER COX, California EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York NATHAN DEAL, Georgia FRANK PALLONE, Jr., New Jersey RICHARD BURR, North Carolina SHERROD BROWN, Ohio Vice Chairman BART GORDON, Tennessee ED WHITFIELD, Kentucky PETER DEUTSCH, Florida CHARLIE NORWOOD, Georgia BOBBY L. RUSH, Illinois BARBARA CUBIN, Wyoming ANNA G. ESHOO, California JOHN SHIMKUS, Illinois BART STUPAK, Michigan HEATHER WILSON, New Mexico ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ALBERT R. WYNN, Maryland CHARLES W. ‘‘CHIP’’ PICKERING, GENE GREEN, Texas Mississippi KAREN MCCARTHY, Missouri VITO FOSSELLA, New York TED STRICKLAND, Ohio ROY BLUNT, Missouri DIANA DEGETTE, Colorado STEVE BUYER, Indiana LOIS CAPPS, California GEORGE RADANOVICH, California MICHAEL F. -

Governor Bob Taft 2004 State of the State Address “The Jobs Agenda”

Governor Bob Taft 2004 State of the State Address “The Jobs Agenda” Speaker Householder, President White, Minority Leaders DiDonato and Redfern, Lieutenant Governor Bradley, members of the Supreme Court, Statewide Elected Officials, and my fellow Ohioans . I am honored to be with you today, and I am blessed to have with me my partner of 37 years, a wonderful mother for our daughter, Anna, and someone who has given her very best to the people of this state, helping kids stay Smart and Sober, building Habitat houses, and leading volunteers on Make a Difference Day – First Lady Hope Taft. Today I pay special tribute to the men and women in our armed forces protecting our nation. Many of you have family members that have answered that call. Rep. John Boccieri, on active duty with the Air Force Reserve, will soon be deployed to Iraq. Please join me in saluting all of our troops and their families for their sacrifice in defending freedom around the world. Let’s also thank the members of the finest cabinet anywhere in America. They’re doing a terrific job in tough circumstances – please stand and be recognized! From prescription drugs to the budget to the do-not-call bill, we’ve accomplished much together in the last year. I give full credit to the Speaker of the House, Larry Householder; the President of the Senate, Doug White; and, to all of you. Mr. Speaker and Mr. President, thank you for your vision and your leadership. You have been called to lead in turbulent times. You have risen to the challenge, and your efforts have made Ohio a better place. -

Ohio Executive Election Recap: 2014-1958

Ohio Governor's 2014 - *John Kasich (R) - Edward Fitzgerald (D) *Kasich (R) 1,944,848 63.64 % (R) Counties Won 86 Fitzgerald (D) 1,009,359 33.03 % (D) Counties Won 2 Other 101,706 3.33% Variance (R) 935,489 30.61% Variance (R) 84 Ohio Attorney General 2014 - *Mike DeWine (R) - David Pepper (D) *DeWine (R) 1,882,048 61.50 % (R) Counties Won 82 Pepper (D) 1,178,426 38.50 % (D) Counties Won 6 Other 0 0.00% Variance (R) 703,622 22.99% Variance (R) 76 Ohio Auditor 2014 - *Dave Yost (R) - Patrick Carney (D) *Yost (R) 1,711,927 56.98 % (R) Counties Won 82 Carney (D) 1,149,305 38.25 % (D) Counties Won 6 Other 143,363 4.77% Variance (R) 562,622 18.73% Variance (R) 76 Ohio Secretary of State 2014 - *Jon Husted (R) - Nina Turner (D) *Husted (R) 1,811,020 59.83 % (R) Counties Won 86 Turner (D) 1,074,475 35.50 % (D) Counties Won 2 Other 141,292 4.67% Variance (R) 736,545 24.33% Variance (R) 84 Ohio Treasurer 2014 - *Josh Mandel (R) - Connie Pillich *Mandel (R) 1,724,060 56.58 % (R) Counties Won 82 Pillich (D) 1,323,325 43.42 % (D) Counties Won 6 Other 0 0.00% Variance (R) 400,735 13.15% Variance (R) 76 Ohio Governor 2010 * John R. Kasich (R) - Ted Strickland (D) *Kasich (R) 1,889,186 49.04 % (R) Counties Won 61 Strickland (D) 1,812,059 47.04 % (D) Counties Won 27 Other 151,228 3.93% Variance (R) 77,127 2.00 % Variance (R) 34 Ohio Attorney General 2010 *Mike DeWine (R) - Richard Cordray (D) *DeWine (R) 1,821,414 47.54 % (R) Counties Won 71 Cordray (D) 1,772,728 46.26 % (D) Counties Won 17 Other 237,586 6.20% Variance (R) 48,686 1.27% Variance (R) 54 -

Ohio Senate Journal

JOURNALS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OHIO SENATE JOURNAL THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2005 371 SENATE JOURNAL, THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2005 THIRTY-SEVENTH DAY Senate Chamber, Columbus, Ohio Thursday, April 7, 2005, 11:00 o'clock a.m. The Senate met pursuant to adjournment. Pursuant to Senate Rule No. 3, the Clerk called the Senate to order. Senator Schuring was selected to preside according to the rule. The journal of the last legislative day was read and approved. INTRODUCTION AND FIRST CONSIDERATION OF BILLS The following bill was introduced and considered the first time: S. B. No. 120-Senators Grendell, Coughlin, Fingerhut. To amend sections 3704.035, 3704.05, 3704.141, 3704.143, 3704.16, 3704.99, 3706.01, 4503.03, 4503.10, 4503.102, 4503.103, 4503.51, 5552.01, and 5739.02, to enact sections 3704.20, 3704.21, 3704.22, 3704.23, and 4503.043, and to repeal sections 3704.14, 3704.142, and 3704.17 of the Revised Code regarding motor vehicle emissions inspections. OFFERING OF RESOLUTIONS Pursuant to Senate Rule No. 54, the following resolutions were offered: S. R. No. 55-Senator Schuring. Honoring Jeff Young as the 2005 NAIA Division II Men's Basketball Coach of the Year. S. R. No. 56-Senator Schuring. Honoring the Walsh University men's basketball team as the 2005 NAIA Division II Champion. S. R. No. 57-Senator Schuring. Honoring the Canton McKinley High School boys basketball team as the 2005 Division I State Champion. The question being, "Shall the resolutions listed under the President's prerogative be adopted?" So the resolutions were adopted. -

Gambling on the Ohio Legislature: Contributions from the Gambling Industry and Proponents 1999-2002

Gambling on the Ohio Legislature: Contributions from the gambling industry and proponents 1999-2002 Catherine Turcer, Campaign Reform Director Patty Lynch, Database Manager Citizens Policy Center November 24, 2002 Gambling Contributions Total Over $1 Million Ohio Candidates and political party committees received $1,035,069 from the gambling industry and proponents from 1999 through the most recent filings. Current members of the Ohio General Assembly received a total of $220,525. Speaker of the House Larry Householder alone received $38,550. Political party and caucus committees received $685,926. The gambling industry lives up to their name. Governor Bob Taft, a vocal opponent of expanding gambling received $60,450. Top organizational contributors to candidates and Ohio political party and caucus committees— · Horsemen’s Benevolent & Protective Association, $152,550 · Ohio Harness Horsemen’s Association, $111,650 · Northfield Park, $47,568 Contributions from proponents of gambling to Ohio’s Republican National State Elections Committee totaled $554,076. Top contributors include- · Stanley Fulton, Anchor Gaming $500,000 · Stephen Wynn, Former Owner of the Mirage & CEO of Wynn Resorts $49,000 · Larry Ruvo, Board Member of American Gaming Association $5,000 These major donors are all from Las Vegas, Nevada. Lobbyists for the gambling industry who represent multiple clients contributed a total of $142,481. Lobbyists Neil S. Clark and Paul Tipps advocate for International Gaming Technology (IGT) and together contributed $82,038. Anti-gambling contributions, including Ohio Roundtable employees, totaled only $300. Background Senator Louis Blessing (R-Cincinnati) introduced legislation on November 19, 2002 that would expand gambling in Ohio. Senate Bill 313 (SB 313) would allow Ohio’s seven racetracks to operate electronic gaming devices, or video slot machines. -

Abolition of the Ohio Death Penalty?—Not for Lack of Trying

Abolition of the Ohio Death Penalty?—Not for Lack of Trying Professor Emerita Margery Malkin Koosed* Nationally, the death penalty is dwindling. Twenty-nine states now have the death penalty,1 down from thirty-eight states twelve years ago.2 Of those twenty- nine, four states have declared a moratorium on executions,3 including California, * University of Akron School of Law Professor Emerita Margery Koosed has been extensively involved in efforts to reform or abolish the death penalty through her writings, presentations, and testimony before Ohio Legislative Committees. As co-counsel, Professor Koosed represented four Akron-area death-row inmates on petitions for certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1976–1978. She has also served as a Commissioner on the Ohio Public Defender Commission by appointment of Governor Richard Celeste (1983–1991), and as Coordinator of the Ohio Death Penalty Task Force, (November 1981 to 1989), (1993 to 1999) organized by the Ohio Criminal Defense Lawyers Association (now known as the Ohio Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers); both positions focus on assuring adequate defense representation is provided in capital cases. She joined the law faculty in 1974 in the Appellate Review Office and teaches in the areas of criminal law and procedure, as well as capital punishment litigation. For decades, Professor Koosed has also served on the Ohio State Bar Association Criminal Justice Committee and occasionally chaired or co-chaired its subcommittee on the death penalty. She was a contributor to a death penalty report produced by said Committee, which called for a cessation of executions until specified reforms could be made. -

A Conversation with Bob Taft

In This Issue The Director’s Chair .........................1 A Conversation with Bob Taft.........1 Reviews ..............................................3 New Books ........................................3 Coming Soon ....................................5 Connecting Readers and Ohio Writers September/October 2014 A Conversation with Bob Taft The Director’s Chair by David Weaver Dear Friends, On October 10, the Ohioana BT: Thanks, David. The Ohioana Library will celebrate its 85th Library has always had a special Eighty-five years—and counting. anniversary and present the 2014 significance for Hope and me-as On October 5, 1929, Ohio First Ohioana Awards in a special event a place that helps create an Ohio Lady Martha Kinney Cooper held at the Ohio Statehouse. We identity by highlighting and convened a meeting of thirteen are honored that former Ohio preserving the works of Ohio leaders from across the state to Governor Bob Taft will join us authors. set up an organization that would as a special guest and to accept solicit the donation of books by the Ohioana Book Award on DW: Governor, Theodore Ohio authors and on Ohio subjects behalf of presidential historian Roosevelt and William Howard for the library at the Governor’s Doris Kearns Goodwin. Her latest Taft made a great team in that Mansion. By the end of that book, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore historic period we know as the meeting, a board of trustees had Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Progressive Era that Doris Kearns been formed, a list of objectives and the Golden Age of Journalism, Goodwin writes about in The Bully adopted, and a director chosen. The is this year’s winner in the About Pulpit. -

The People's Art Collection Portraits of Governor

The People’s Art Collection Ohio Alliance for Arts Education The People’s Art Collection Portraits of Governor Taft and Governor Voinovich The Ohio Alliance for Arts Education, in partnership with the Ohio Arts Council and the Capitol Square Review and Advisory Board, has developed a set of teacher resources for works of art found at the Ohio Statehouse located in Columbus, Ohio. The teacher resources are individual lessons from The People’s Art Collection. In a world where arts education is the core to learning in other academic areas, and on its own, it is fitting that the works of art found at the Ohio Statehouse become an integral part of the visiting students’ experience. These works of art are available to the public year round and are considered to be an added value to students taking a classic Statehouse tour. School age children and their teachers visit the Statehouse to discover the building’s history and architecture as well as to observe state government in action. There are more than 100,000 Statehouse tour participants annually. The People’s Art Collection provides integrated lessons for use by educators and parents to take the learning back home and to the school house! Students who are unable to visit the Ohio Statehouse in person may now experience the arts through the lessons and virtual art exploration experience on the website of the Ohio Statehouse at: www.ohiostatehouse.org. The Ohio Alliance for the Arts Education believes that classroom teachers will use the arts learning resources from The People’s Art Collection as part of their integrated approach to teaching history, civics, and the arts.