Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Today by Charles

This script was freely downloaded from the (re)making project, (charlesmee.org). We hope you'll consider supporting the project by making a donation so that we can keep it free. Please click here to make a donation. Today by C H A R L E S L . M E E Music. A guy brings out a wooden box and puts it down and throws 15 or 20 wine bottles into it throws them so hard they all shatter and then he sticks his head down into the box and does a head stand and he gets a guy to stand on his neck or the back of his head to shove his head down hard into the box and then he stands up and his head and his face are covered with blood and it wasn’t a trick he didn’t have a trick he just cut himself up all over his head. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. Music. 1 People come through from one side to the other, in and out: The five year old girl, eating an ice cream cone, smiling, sitting in a red wagon pulled by her father. A golf cart, driven like crazy by a caddy, while, in the back, a couple embraces passionately. A couple being pulled along on a picnic blanket with food and a champagne bottle in a bucket, and she is drinking and drinking and drinking the champagne. An electric wheelchair— a man driving, a woman sitting on the handlebars, she running her fingers through his hair over and over and over. -

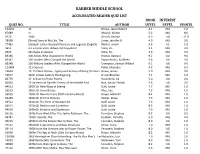

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous”

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous” Genesis 10:1, 8-10 (NLT), “This is the account of the families of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the three sons of Noah. Many children were born to them after the great flood… 8 C ush was also the ancestor of Nimrod, who was the first heroic warrior on earth. 9 S ince he was the greatest hunter in the world, his name became proverbial. People would say, “This man is like Nimrod, the greatest hunter in the world.” 10 H e built his kingdom in the land of Babylonia, with the cities of Babylon, Erech, Akkad, and Calneh.” →Nimrod’s pride leads him to build a city that would become Babylon, which is a type or picture in the Bible of human pride in rebellion against God. This idea finds its fullest description in the Book of Revelation, as God pronounces His final judgment on the pride and wickedness of mankind in the last days: Revelation 17:1-6 (NLT), “One of the seven angels who had poured out the seven bowls came over and spoke to me. “Come with me,” he said, “and I will show you the judgment that is going to come on the great prostitute, who rules over many waters. 2 T he kings of the world have committed adultery with her, and the people who belong to this world have been made drunk by the wine of her immorality.” So, the angel took me in the Spirit= into the wilderness. There I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that had seven heads and ten horns, and blasphemies against God were written all over it. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Midnight Mass Around the World the Denver Catholic Register

e*eeKr*-wewi*mwie*"'ieweeief«F*aK--r-~tewaee3* Services on TV | Th* Solemn Midnight Men in the Cathedral on : Chriitm ai will bo toleyited by KOA.TV, Channel 4. The R ot. Owen McHugh of the j j Cathedral ataff will be the j narrator. There will be no ' radio broadcast of tbe cere* j moniea, which had been car- ! ried annually by KOA for about 20 yean. Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Archbishop^s Contents Copyright by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., I960—Permission to Reproduce, Except on ArUcles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Christmas DBtVEROJHOUC Message At this holy season, I proy you a very blessed and happy Christmas filled with REGISTER the consolations of the Infant Savior, VOL. LII. No. 19. THURSDAY, DECEMBER 20, 1956 DENVER, COLORADO The anniversary of His coming into the world brings a heavenly consolation to earth. It raises us above the sordid things 11 of life to contemplate the majesty and love 1,380 Youths Enrolled of on Infinite God to sanctify this world of ours and moke it godly. Divinity becomes a helpless little Babe to draw us to our Maker. Scout Activities In gratitude for God's fovors to us and in appreciation of the great gift of faith in Him, I trust each Catholic will receive Holy Communion on Christmas Day. I will offer my Holy Mass at midnight for your inten tions that the good God bless you spiritually Develop in Area ond moteriolly ond fill your lives with many consolations. ' steady f^rowtli in tlie Catholic Scouting In many lands and for many God-loving program of the Denver area is shown in the an people under Communistic domination, nual report presented this week to Archbishop Archbishop Christmas this year will be another night mare of persecution and privation. -

Videodiskothek Sunrise Playlist: Pink Floyd Garten Party – 26.08.2017

Videodiskothek Sunrise Playlist: Pink Floyd Garten Party – 26.08.2017 Quelle: http://www.videodiskothek.com The Orb + David Gilmour - Metallic Spheres (audio only) Alan Parsons + David Gilmour - Return To Tunguska (audio only) Pink Floyd - The Dark Side Of The Moon (full album) Roger Waters - Wait For Her David Gilmour - Rattle That Lock Pink Floyd - Another Brick In The Wall Pink Floyd - Marooned Pink Floyd - On The Turning Away Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here (live) Pink Floyd - The Gunners Dream Pink Floyd - The Final Cut Pink Floyd - Not Now John Pink Floyd - The Fletcher Memorial Home Pink Floyd - Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun Pink Floyd - High Hopes Pink Floyd - The Endless River (full album) [LASERSHOW] Pink Floyd - Cluster One Pink Floyd - What Do You Want From Me Pink Floyd - Astronomy Domine Pink Floyd - Childhood's End Pink Floyd - Goodbye Blue Sky Pink Floyd - One Slip Pink Floyd - Take It Back Pink Floyd - Welcome To The Machine Pink Floyd - Pigs On The Wing Roger Waters - Dogs (live) David Gilmour - Faces Of Stone Richard Wright + David Gilmour - Breakthrough (live) Pink Floyd - A Great Day For Freedom Pink Floyd - Arnold Lane Pink Floyd - Mother Pink Floyd - Anisina Pink Floyd - Keep Talking (live) Pink Floyd - Hey You Pink Floyd - Run Like Hell (live) Pink Floyd - One Of These Days Pink Floyd - Echoes (quad mix) [LASERSHOW] Pink Floyd - Shine On You Crazy Diamond Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here Pink Floyd - Signs Of Life Pink Floyd - Learning To Fly David Gilmour - In Any Tongue Roger Waters - Perfect Sense (live) David Gilmour - Murder Roger Waters - The Last Refugee Pink Floyd - Coming Back To Life (live) Pink Floyd - See Emily Play Pink Floyd - Sorrow (live) Roger Waters - Amused To Death (live) Pink Floyd - Wearing The Inside Out Pink Floyd - Comfortably Numb. -

Plinius Senior Naturalis Historia Liber V

PLINIUS SENIOR NATURALIS HISTORIA LIBER V 1 Africam Graeci Libyam appellavere et mare ante eam Libycum; Aegyptio finitur, nec alia pars terrarum pauciores recipit sinus, longe ab occidente litorum obliquo spatio. populorum eius oppidorumque nomina vel maxime sunt ineffabilia praeterquam ipsorum linguis, et alias castella ferme inhabitant. 2 Principio terrarum Mauretaniae appellantur, usque ad C. Caesarem Germanici filium regna, saevitia eius in duas divisae provincias. promunturium oceani extumum Ampelusia nominatur a Graecis. oppida fuere Lissa et Cottae ultra columnas Herculis, nunc est Tingi, quondam ab Antaeo conditum, postea a Claudio Caesare, cum coloniam faceret, appellatum Traducta Iulia. abest a Baelone oppido Baeticae proximo traiectu XXX. ab eo XXV in ora oceani colonia Augusti Iulia Constantia Zulil, regum dicioni exempta et iura in Baeticam petere iussa. ab ea XXXV colonia a Claudio Caesare facta Lixos, vel fabulosissime antiquis narrata: 3 ibi regia Antaei certamenque cum Hercule et Hesperidum horti. adfunditur autem aestuarium e mari flexuoso meatu, in quo dracones custodiae instar fuisse nunc interpretantur. amplectitur intra se insulam, quam solam e vicino tractu aliquanto excelsiore non tamen aestus maris inundant. exstat in ea et ara Herculis nec praeter oleastros aliud ex narrato illo aurifero nemore. 4 minus profecto mirentur portentosa Graeciae mendacia de his et amne Lixo prodita qui cogitent nostros nuperque paulo minus monstrifica quaedam de iisdem tradidisse, praevalidam hanc urbem maioremque Magna Carthagine, praeterea ex adverso eius sitam et prope inmenso tractu ab Tingi, quaeque alia Cornelius Nepos avidissime credidit. 5 ab Lixo XL in mediterraneo altera Augusta colonia est Babba, Iulia Campestris appellata, et tertia Banasa LXXV p., Valentia cognominata. -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

Death and the Afterlife Among the Classic Period Royal Tombs of Copán, Honduras

To Be Born an Ancestor: Death and the Afterlife among the Classic Period Royal Tombs of Copán, Honduras The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Fierer-Donaldson, Molly. 2012. To Be Born an Ancestor: Death Citation and the Afterlife among the Classic Period Royal Tombs of Copán, Honduras. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 3:28:47 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9548615 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) © 2012 – Molly Fierer-Donaldson All rights reserved William L. Fash Molly Fierer-Donaldson To Be Born an Ancestor: Death and the Afterlife Among the Classic Period Royal Tombs of Copán, Honduras Abstract This goal of this dissertation is to participate in the study of funerary ritual for the Classic Maya. My approach evaluates comparatively the seven royal mortuary contexts from the city of Copán, Honduras during the Classic period from the early 5th century to early 9th century CE, in order to draw out the ideas that infused the ritual behavior. It is concerned with analyzing the tomb as a ritual context that is a materialization of a community's ideas about death and the afterlife. The heart is the data gathered from my participation in the excavation of the Classic period royal tomb called the Oropéndola Tomb.