Volume 8, Number 5, September 11, 2015 INSUFFICIENT MARGINS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alone Across the Atlantic

® 8 - DECEMBER 2013 www.kitplanes.com RV Atlantic Across in an in Swage Fittings Swage Secure? Cables Your Are the Adventure FT A Alone T REVIEW H ’S GUIDE SHOP R E H Easy Fiberglass Prep Aerodynamic Bookworm Tire Changing 101 T Soaring on Homemade Wings 2014 BUYER’S GUIDE2014 ISSUE! N • • • I HP-24 FLIG HP-24 BUYE Over 350 Planes Listed! Planes 350 Over 2014 KIT AIRCR KITPLANES DECEMBER 2013 Kit Buyer’s Guide • Transatlantic RV-8 • HP-24 Sailplane • Design to Fit • Swagelocks • Dawn Patrol • Testing to DO-160 • Home Shop Machines BELVOIR PUBLICATIONS Enjoy the Freedom of Homebuilt Aircraft Weather the Storm with SkyView’s IFR Capabilities Redundant flight instruments that automatically cross-check each other • ADS-B traffic and weather in-flight • SkyView network modules that detect wiring faults without losing capability • Li-Ion backup batteries that keep your SkyView system up when the power goes down • Autopilot with fully coupled ILS and GPS WAAS/LPV approaches. SkyView should already be your IFR platform of choice. But if that’s not enough, SkyView 7.0 introduces geo-referenced instrument approach charts, airport diagrams, and the best mapping software we’ve ever built. Go Fly! www.DynonAvionics.com 425-402-0433 [email protected] Seattle,Washington December 2013 | Volume 30, Number 12 Annual Buyer’s Guide, Part 1 26 2014 KIT AIRCRAFT BUYER’S GUIDE: The state of the kit world is sound. By Paul Dye and Mark Schrimmer. 38 KIT AIRCRAFT QUICK REFERENCE: A brief overview of available kit aircraft for 2014. Compiled by Richard VanderMeulen and Omar Filipovic. -

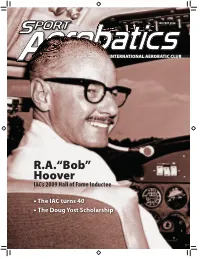

“Bob” Hoover IAC’S 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee

JANUARY 2010 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE OFOF TTHEHE INTERNATIONALI AEROBATIC CLUB R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee • The IAC turns 40 • The Doug Yost Scholarship PLATINUM SPONSORS Northwest Insurance Group/Berkley Aviation Sherman Chamber of Commerce GOLD SPONSORS Aviat Aircraft Inc. The IAC wishes to thank Denison Chamber of Commerce MT Propeller GmbH the individual and MX Aircraft corporate sponsors Southeast Aero Services/Extra Aircraft of the SILVER SPONSORS David and Martha Martin 2009 National Aerobatic Jim Kimball Enterprises Norm DeWitt Championships. Rhodes Real Estate Vaughn Electric BRONZE SPONSORS ASL Camguard Bill Marcellus Digital Solutions IAC Chapter 3 IAC Chapter 19 IAC Chapter 52 Lake Texoma Jet Center Lee Olmstead Andy Olmstead Joe Rushing Mike Plyler Texoma Living! Magazine Laurie Zaleski JANUARY 2010 • VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 1 • IAC SPORT AEROBATICS CONTENTS FEATURES 6 R.A. “Bob” Hoover IAC’s 2009 Hall of Fame Inductee – Reggie Paulk 14 Training Notes Doug Yost Scholarship – Lise Lemeland 18 40 Years Ago . The IAC comes to life – Phil Norton COLUMNS 6 3 President’s Page – Doug Bartlett 28 Just for Starters – Greg Koontz 32 Safety Corner – Stan Burks DEPARTMENTS 14 2 Letter from the Editor 4 Newsbriefs 30 IAC Merchandise 31 Fly Mart & Classifieds THE COVER IAC Hall of Famer R. A. “Bob” Hoover at the controls of his Shrike Commander. 18 – Photo: EAA Photo Archives LETTER from the EDITOR OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Publisher: Doug Bartlett by Reggie Paulk IAC Manager: Trish Deimer Editor: Reggie Paulk Senior Art Director: Phil Norton Interim Dir. of Publications: Mary Jones Copy Editor: Colleen Walsh Contributing Authors: Doug Bartlett Lise Lemeland Stan Burks Phil Norton Greg Koontz Reggie Paulk IAC Correspondence International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

September 2007 Newsletter

STRAIGHT SCOOP Volume XIII Number 9 September 2007 PACIFIC COAST AIR MUSEUM To promote the acquisition, restoration, safe operation, and display of historical aircraft and provide an educational venue for the community 20 August 2007 Dear Dave, Each Year I think that year’s Air Show couldn’t be beat. This year you proved me wrong again! The Pacific Coast Air Museum Air Show excelled in every aspect; the performances, the timing, static displays, announcements, traffic control and parking, the Pilot’s Tent and so many others. I can only imagine how hard you and your folks work in planning for and implementing this very significant contribution to avia- tion and Sonoma County. I am very impressed with the spirit of every one of the PCAM members and the host of volunteers. A big thanks to you and those who helped plan and carry out this memorable event. Sincerely, Jim Eade, General, United States Air Force (Retired) Air Show Survivor’s BBQ We had one terrific Air Show. By every measure, it was the best ever. Now, for those members who helped put on our Air Show, the Survivor’s BBQ is a chance to relax, pat ourselves on the back, tell “war stories”, and have a good time without all the stress of Air Show prep, or Air Show day, or Air Show take down, or Air Show put away. DATE: Saturday, September 22nd PLACE: East Patio, Pacific Coast Air Museum TIME: 3:00 PM until ??? (we have lights now!!). We will supply the meat, bread, salad, wine, beer, and soft drinks and water. -

U.S. National Aerobatic Championships

November 2012 2012 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB Vol. 41 No. 11 November 2012 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB CONTENTSOFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB At the 2012 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships, 95 competitors descended upon the North Texas Regional Airport in hopes of pursuing the title of national champion and for some, the distinguished honor of qualifying for the U.S. Unlimited Aerobatic Team. –Aaron McCartan FEATURES 4 2012 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships by Aaron McCartan 26 The Best of the Best by Norm DeWitt COLUMNS 03 / President’s Page DEPARTMENTS 02 / Letter From the Editor 28 / Tech Tips THE COVER 29 / News/Contest Calendar This photo was taken at the 30 / Tech Tips 2012 U.S. National Aerobatic Championships competition as 31 / FlyMart & Classifieds a pilot readies to dance in the sky. Photo by Laurie Zaleski. OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB REGGIE PAULK COMMENTARY / EDITOR’S LOG OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB PUBLISHER: Doug Sowder IAC MANAGER: Trish Deimer-Steineke EDITOR: Reggie Paulk OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB VICE PRESIDENT OF PUBLICATIONS: J. Mac McClellan Leading by example SENIOR ART DIRECTOR: Olivia P. Trabbold A source for inspiration CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Jim Batterman Aaron McCartan Sam Burgess Reggie Paulk Norm DeWittOFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB WHILE AT NATIONALS THIS YEAR, the last thing on his mind would IAC CORRESPONDENCE I was privileged to visit with pilots at be helping a competitor in a lower International Aerobatic Club, P.O. -

Airventure 2011 the IAC’S Perspective

OCTOBER 2011 OFFICIALOFFICIAL MAGAZINEMAGAZINE ofof thethe INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL AEROBATICAEROBATIC CLUBCLUB AirVenture 2011 The IAC’s Perspective • Restoring a Baby Lakes • Building Bridges CONTENTS Vol. 40 No. 10 October 2011 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB The aerobatic spirit, passion, and community are alive and well north of the border. –Mike Tryggvason FEATURES 06 AirVenture 2011 From the IAC’s perspective by Reggie Paulk 14 Restoring a Baby Lakes by Ron Bearer Jr. 22 Building Bridges by Mike Tryggvason COLUMNS 02 / Tech Tips Vicki Cruse 05 / Gone West Jeffrey Granger 29 / Ask Allen Allen Silver DEPARTMENTS THE COVER Pilot Jeff Boerboon 01 / Letter From the Editor performing at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2011. 04 / News Briefs 30 / Contest Calendar Advertising Index Photo by 31 / Classifieds and FlyMart DeKevin Thornton PHOTOGRAPHY BY LARRY ERNEWEIN REGGIE PAULK COMMENTARY / EDITOR’S LOG OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB PUBLISHER: Doug Bartlett IAC MANAGER: Trish Deimer EDITOR: Reggie Paulk SENIOR ART DIRECTOR: Phil Norton DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: Mary Jones COPY EDITOR: Colleen Walsh CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Ron Bearer Vicki Cruse Reggie Paulk Allen Silver Mike Tryggvason IAC CORRESPONDENCE International Aerobatic Club, P.O. Box 3086 Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086 Tel: 920.426.6574 • Fax: 920.426.6579 Heading Into Fall E-mail: [email protected] PUBLICATION ADVERTISING BY THE TIME YOU read this, Nationals will located where a lot of the main action have wrapped up, and we’ll be nearly fi n- takes place. Th is gives members a great MANAGER, DOMESTIC: Sue Anderson ished with what appears to have been a opportunity to not only rest their feet, but Tel: 920-426-6127 very successful contest season. -

Diamond DA20-C1 Eclipse Arrives in NZ Wings Over Wairarapa Places to Go: Stewart Island Products, Services, News, Events, Warbirds, Recreation, Training and More

KiwiFlyerTM The New Zealand Aviators’ Marketplace Issue 26 2013 #1 $ 5.90 inc GST ISSN 1170-8018 Diamond DA20-C1 Eclipse arrives in NZ Wings Over Wairarapa Places to Go: Stewart Island Products, Services, News, Events, Warbirds, Recreation, Training and more. KiwiFlyer Issue 26 2013 #1 From the Editor In this issue Welcome to our first issue of KiwiFlyer for 2013. 6. Diamond DA20-C1 Eclipse Arrives in NZ The aviation year is already well underway with Eagle Flight Training at Ardmore have just airshows and fly-ins happening somewhere in the taken delivery of a Diamond DA20. We take a country almost on a weekly basis. Compared to the look at their brand new aircraft. last few years, we have enjoyed some outstanding weather in January too. There’s been no excuse not 12. Flying in the Wooden Wonder to fully indulge one’s passion for flying. Before its last flight in New Zealand, Gavin Conroy was one of the lucky few people to get Our cover picture is of Eagle Flight Training’s new to fly in the de Havilland Mosquito. Diamond DA20, the first in NZ to be optioned TM 14. AIRCARE Compliance simplified with a Garmin G500 glass cockpit and also the first TM Diamond to go into a training role outside of the HeliA1 have recently attained AIRCARE large fleets operated by CTC and Massey University accreditation with the help of Air Maestro School of Aviation. We took a look at this new software from Avinet. aircraft when it was delivered in January. 1 7. -

FEDERATION AERONAUTIQUE INTERNATIONALE MSI - Avenue De Rhodanie 54 – CH-1007 Lausanne – Switzerland

FAI Sporting Code Section 4 – Aeromodelling Volume F3 Radio Control Aerobatics 2019 Edition Effective 1st January 2019 F3A - R/C AEROBATIC AIRCRAFT F3M - R/C LARGE AEROBATIC AIRCRAFT F3P - R/C INDOOR AEROBATIC AIRCRAFT F3S - R/C JET AEROBATIC AIRCRAFT (PROVISIONAL) ANNEX 5A - F3A DESCRIPTION OF MANOEUVRES ANNEX 5B - F3 R/C AEROBATIC AIRCRAFT MANOEUVRE EXECUTION GUIDE ANNEX 5G - F3A UNKNOWN MANOEUVRE SCHEDULES Maison du Sport International Avenue de Rhodanie 54 ANNEX 5C - F3M FLYING AND JUDGING GUIDE CH-1007 Lausanne ANNEX 5M - F3P DESCRIPTION OF MANOEUVRES Switzerland Tel: +41(0)21/345.10.70 ANNEX 5X - F3S DESCRIPTION OF MANOEUVRES Fax: +41(0)21/345.10.77 ANNEX 5N - F3A, F3P, F3M WORLD CUP RULES Email: [email protected] Web: www.fai.org FEDERATION AERONAUTIQUE INTERNATIONALE MSI - Avenue de Rhodanie 54 – CH-1007 Lausanne – Switzerland Copyright 2019 All rights reserved. Copyright in this document is owned by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Any person acting on behalf of the FAI or one of its Members is hereby authorised to copy, print, and distribute this document, subject to the following conditions: 1. The document may be used for information only and may not be exploited for commercial purposes. 2. Any copy of this document or portion thereof must include this copyright notice. 3. Regulations applicable to air law, air traffic and control in the respective countries are reserved in any event. They must be observed and, where applicable, take precedence over any sport regulations. Note that any product, process or technology described in the document may be the subject of other Intellectual Property rights reserved by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale or other entities and is not licensed hereunder. -

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’S Note to Flightlab Students

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’s Note to Flightlab Students The collection of documents assembled here, under the general title “Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight,” covers a lot of ground. That’s because unusual-attitude training is the perfect occasion for aerodynamics training, and in turn depends on aerodynamics training for success. I don’t expect a pilot new to the subject to absorb everything here in one gulp. That’s not necessary; in fact, it would be beyond the call of duty for most—aspiring test pilots aside. But do give the contents a quick initial pass, if only to get the measure of what’s available and how it’s organized. Your flights will be more productive if you know where to go in the texts for additional background. Before we fly together, I suggest that you read the section called “Axes and Derivatives.” This will introduce you to the concept of the velocity vector and to the basic aircraft response modes. If you pick up a head of steam, go on to read “Two-Dimensional Aerodynamics.” This is mostly about how pressure patterns form over the surface of a wing during the generation of lift, and begins to suggest how changes in those patterns, visible to us through our wing tufts, affect control. If you catch any typos, or statements that you think are either unclear or simply preposterous, please let me know. Thanks. Bill Crawford ii Bill Crawford: WWW.FLIGHTLAB.NET Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight © Flight Emergency & Advanced Maneuvers Training, Inc. -

Volume 21 Number 4 (Journal 703) April, 2018

IN THIS ISSUE President’s Letter Page 3 Articles Page 17-1 Vice President’s Letter Page 4 Letters Page 52-57 Secretary/Treasurer’s Letter Page 4-5 In Memoriam Page –57-58 Local Reports Page 5-17 Calendar Page 60 Volume 21 Number 4 (Journal 703) April, 2018 —— OFFICERS —— President Emeritus: The late Captain George Howson President: Bob Engelman………………………………………....954-436-3400…………………………………….………[email protected] Vice President: John Gorczyca…………………………………..916-941-0614……………...………………………………[email protected] Sec/Treas: John Rains……………………………………………..802-989-8828……………………………………………[email protected] Membership Larry Whyman……………………………………...707-996-9312……………………………………[email protected] —— BOARD OF DIRECTORS —— President - Bob Engelman — Vice President — John Gorczyca — Secretary Treasurer — John Rains Rich Bouska, Phyllis Cleveland, Cort de Peyster, Ron Jersey, Walt Ramseur Jonathan Rowbottom, Leon Scarbrough, Bill Smith, Cleve Spring, Larry Wright —— COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN —— Cruise Coordinator……………………………………..Rich Bouska………………. [email protected] Eblast Chairman……………………………………….. Phyllis Cleveland .................... [email protected] RUPANEWS Manager/Editor………………………… Cleve Spring ........................... [email protected] RUPA Travel Rep………..…………………………….. Pat Palazzolo ................... [email protected] Website Coordinator………………………………….. Jon Rowbottom .................... rowbottom0@aol,com Widows Coordinator…………………………………... Carol Morgan .................. [email protected] Patti Melin ....................... [email protected] -

Medlemstidning För EAA Sverige • #4/2016 • Årgång 49

Medlemstidning för EAA Sverige • #4/2016 • årgång 49 Ur innehållet: TC informerar, Värm motor på vintern, Dra lärdom av haverier, Pietenpol Air Camper, MFI-9, Pitts Model 12, NILZ (Zlin), Flygäventyr I detta nummer Bland annat: Flygkalendern 2016 Haverier 2016 Tragiska händelser att dra lärdomar av. 15 dec Julfika på kansliet, Barkarby. från kl 18.00 8 2017 4 mars EAA Sverige årsmöte kl 13.00. EAA Pietenpol Air Camper, Per Widing flyger kansli, Barkarby 5-8 april Aero, Friedrichshafen 25-28 maj Piper Cub fyller 80 år firas på Höganäs flygplats ESMH 3-4 juni EAA Sverige fly-in, Falköping 12 30 juni-2 juli Experimental days EBLE, Leopoldsburg, Belgium 7-9 juli Årrenjarka sjöflygträff, Kenneth Hagesten kan kontaktas på telefon 070-5370162 eller e-post kenneth.hagesten@ telia.com Pitts Model 12 Det händer i vårt östra grannland, Finland. 24-30 juli EAA flyin, Wittman Regional Airport, Oshkosh, WI, USA 20 augusti Eksjö flygdag 14 kurser Se sid 11 18 En annorlunda Zlin, Senaste datum för material för kommande nummer: 2017 1/2017: 6 februari 2/2017: 24 april 3-4/2017: 4 september MFI-9 är populära 5/2017: 13 november 20 En nyrenoverad maskin pressenteras En flygning till Istanbul Läs och inspireras Omslaget: 22 Pietenpol Air Camper. Per Widings klassiker som ni kan läsa om i detta nummer. Foto: Peter Liander 2 eaa-nytt #4/2016 ordförandens krönika Några ord från ordföranden EAA -NYTT Nr 4/2016 | Årgång 49 Några rader……… Hösten och lugnet har infunnit sig. Det hän- ner. Det är dock svårt att applicera på våra Medlemsorgan för EAA Sverige der inte så mycket inom EAA just nu, jag luftfartyg, vilka skall få bidrag, vem väljer ut och EAA Chapter 222 Sverige Redaktör: Lennart Öborn. -

FLYING MODELS 3 DECEMBER 1998 Vol

December 1998 $3.50 Canada $5.25 1-\ it~~ r.t h.HJ~~ ~i H13 p[)puh.tt !.. ~n]~t n ~ C'J ;.· :: ; ·~t :.:.,/ !) __,_L 1 :;.,~_, __.V[)!) J''J.l .....r GREAT HOLIDAY GIFTS ARE AT YOUR LOCAL HOBBY SHOP Pre-assembled and Fully Decorated Scale Plastic Airplanes Starting at $10.98 Includes stand and workmg prop mechanism (warbirds) and retractable lanaing gear. ~--------~---- 1/72 $15 More Great Gift Ideas- Plastic Scale Model Kits Affordable - Fun To Build - Looks Great Sca le: 1:700 (approx. 12") Scale: 1:700 (approx. 12") Scale:1:150 (approx. 20") #2104 #2102 Sca le:! :600 #0901 #3603 Other Motorized Battleships: # 3601 U.S.S. Iowa $1 3.98 #3602 U.S.S. New Jersey $1 3.98 #3603 U.S.S. Wisconsin $13.98 Destroyer Miss/e Cruiser Scale : 1: 550 (approx. 19") Scale: 1: 700 (approx. 12") Scale:1:700 (approx. 12") #1085 Coast Guard #1084 Sailing Ship ,..........-------------, Other cruisers available: # 1083 U.S.S. Bunker Hill $7 .98 # 1087 U.S.S. Mobile Bay $7.98 Scale: 1: 350 #1089 U.S.S. Vella Gu lf $7.98 Scale:1 :72 also available - Russian Helicopter English KA-50 "Hokum" $8.98 Sailing Ship Scale:1:72 Scale: 1: 350 #0 102 Other jet fighters available: A Scale:1 :72 also available: Scale:1 :72 USSR SU-27 Sea Flanker B $9.98 Chilean Sailing Ship #0105 U.S. YF-22A Lightning $9.98 Scale 1:330 also available - U.S. Helicopter French 2000D Mirage $9.98 # 1055 Esmerelda $9.98 #0 104 "Longbow" Apache $8.98 See our other ad featuring Aerotech International kits on page 59 scale·J·n If\\ IUI Q B ~ Direct orders add $4.00 per order · · L!::JARE Ln.J BY ~ ISTRIBUTQRS P.O. -

September Meeting Notes

October 2009 20 Issue 10 September Meeting Notes Hey everybody. Inside this issue: George started off the meeting with a report on the CP event. There were not Meeting Minutes many spectators (the weather was bad that day), but there were 30 registered pilots, so that was good. The demos were excellent and so was the BBQ. The bottom line Lunch Hour was a $5862 donation for United Cerebral Palsy of Colorado. This included some cor- Pitts Special porate sponsors (Jeppesen $2k, Aeroworks $1.5k, the catering company $800, Dex, etc.) There were 25 MAS members who volunteered at the event. Thanks to all of you. Without you, the event would have a been a failure. In addition to your time, the club donated the fees for the extra Porta-potty and also all the work for getting the field looking great. On September 19th, MAS was hosted by Aeroworks at their Aurora headquar- ters. Aeroworks gave members a tour of the facility and showed them what planes are being developed. Our esteemed leader Hank won himself an electric plane in a draw- ing. Just to let all Adams County voters know, one of our members, Mark Nicastle, will be running for Sheriff in the 2010 election. Not to sway any votes, but Mark's a good guy and has done a lot for the club over the years. The October meeting is when we elect officers for 2010. We need volun- teers! (show up and vote/volunteer now is your chance to change things you don't like) Upcoming meetings and events Hank and Ron will not be staying on as President and VP, so we need some Meeting Oct 22 new people for the jobs.