Alice Paul: Warrior for Women’S Equality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Florence Brooks Whitehouse and Maine's Vote to Ratify Women's

Maine History Volume 46 Number 1 Representing Maine Article 4 10-1-2011 Florence Brooks Whitehouse and Maine’s Vote to Ratify Women’s Suffrage in 1919 Anne Gass Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Social History Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gass, Anne. "Florence Brooks Whitehouse and Maine’s Vote to Ratify Women’s Suffrage in 1919." Maine History 46, 1 (2011): 38-66. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol46/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Florence Brooks Whitehouse was a prominent suffrage leader in Maine in the 1910s. Originally a member of the Maine Woman Suffrage Association, White- house became the leader of the Maine branch of the National Woman’s Party, which used more radical tactics and espoused immediate and full suffrage for women. Courtesy of the Sewall-Belmont House & Museum, Washington DC. FLORENCE BROOKS WHITEHOUSE AND MAINE’S VOTE TO RATIFY WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE IN 1919 BY ANNE GASS In 1919, Maine faced an unusual conflict between ratifying the nine- teenth amendment to the United States Constitution that would grant full voting rights to women, and approving a statewide suffrage referen- dum that would permit women to vote in presidential campaigns only. Maine’s pro-suffrage forces had to head off last-minute efforts by anti- suffragists to sabotage the Maine legislature’s ratification vote. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

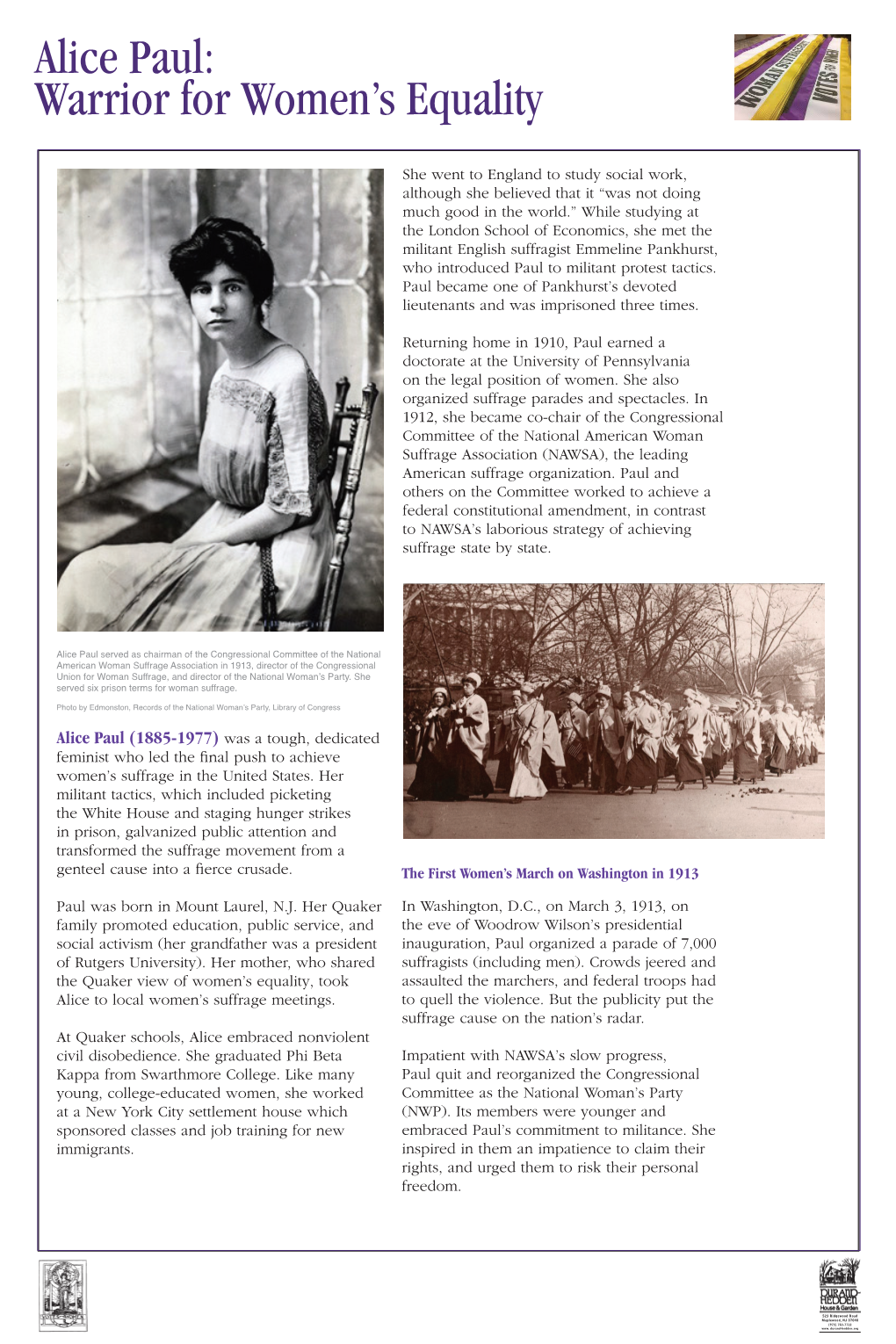

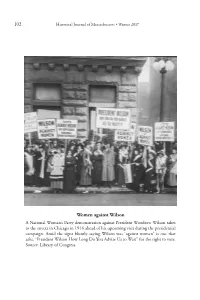

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship Lynda G

Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship Lynda G. Dodd♦ INTRODUCTION 340 I. THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT & UNRULY CONSTITUTIONALISM 344 A. From Partial Histories to Analytical Narratives 346 B. A Case Study of Popular Constitutionalism: The Role of Contentious Politics 353 II. ALICE PAUL’S CIVIC EDUCATION 354 A. A Quaker Education for Social Justice 355 B. A Militant in Training: The Pankhurst Years 356 C. Ending the “Doldrums”: A New Campaign for a Federal Suffrage Amendment 359 III. “A GENIUS FOR ORGANIZATION” 364 A. “The Great Demand”: The 1913 Suffrage Parade 364 B. Targeting the President 372 C. The Rise of the Congressional Union 374 D. The Break with NAWSA 377 E. Paul’s Leadership Style & the Role of “Strategic Capacity” 379 F. Campaigning Against the Democratic Party in 1914 382 G. Stalemate in Congress 387 H. The National Woman’s Party & the Election of 1916 391 ♦ J.D. Yale Law School, 2000, Ph.D Politics, Princeton University, 2004. Assistant Professor of Law, Washington College of Law, American University. Many thanks to the participants who gathered to share their work on “Citizenship and the Constitution” at the Maryland/Georgetown Discussion Group on Constitutionalism and to the faculty attending the D.C.-Area Legal History Workshop. I would like to thank Mary Clark, Ross Davies, Mark Graber, Dan Ernst, Jill Hasday, Paula Monopoli, Carol Nackenoff, David Paull Nickles, Julie Novkov, Alice Ristroph, Howard Schweber, Reva Siegel, Jana Singer, Rogers Smith, Kathleen Sullivan, Robert Tsai, Mariah Zeisberg, Rebecca Zeitlow, and especially Robyn Muncy for their helpful questions and comments. -

National Woman's Party History

DETAILED CHRONOLOGY NATIONAL WOMAN’S PARTY HISTORY 1910-1913 1910 Apr. 14-19 Alice Paul, home after serving time in London prison for suffrage activities in England, addresses National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) annual convention in Washington, D.C. She endorses militant tactics of British suffragettes and describes their campaign as “war of men and women working together against the politicians.” 1912 Dec. Alice Paul appointed chairman of NAWSA’s Congressional Committee at NAWSA convention with support of Harriot Stanton Blatch and Jane Addams. Lucy Burns, Crystal Eastman Benedict, Dora Lewis, and Mary Ritter Beard join committee. NAWSA considers federal action so unimportant it budgets only $10 annually in 1912 to Congressional Committee. Paul told she needs to raise own funds. 1913 Jan. 2 NAWSA’s Congressional Committee establishes office in basement of 1420 F Street NW, Washington, D.C. 1913 Feb.-Mar. Open-air meetings in Washington, D.C., demand Congress pass national woman suffrage amendment and seek to generate interest in suffrage parade scheduled for Mar. 3. Image 1 | Image 2 | Image 3 | Image 4 1913 Feb.12 Rosalie Gardiner Jones, wealthy New York socialite, and British suffragette Elizabeth Freeman, leave Newark, New Jersey, on foot with band of suffrage “pilgrims” for Washington, D.C., to participate in Mar. 3 suffrage parade. They attract significant press and distribute suffrage literature along the way. 1913 Mar. 3 Massive national suffrage parade, Women begin to assemble for the first national organized by Congressional suffrage parade, Washington, D.C. Harris & Ewing. March 3, 1913. Committee and local suffrage About this image groups, held in Washington, D.C., day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. -

The Political Activities of African American Women in Philadelphia, 1912-1941

‘Our girls can match ‘em every time’: The Political Activities of African American Women in Philadelphia, 1912-1941 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY by Jennifer Reed Fry January, 2010 ii © by Jennifer Reed Fry 2010 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT ‘Our girls can match ‘em every time’: The Political Activities of African American Women in Philadelphia, 1912-1941 Jennifer Reed Fry Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2010 Dr. Bettye Collier-Thomas This dissertation challenges the dominant interpretation in women’s history of the 1920s and 1930s as the “doldrums of the women’s movement,” and demonstrates that Philadelphia’s political history is incomplete without the inclusion of African American women’s voices. Given their well-developed bases of power in social reform, club, church, and interracial groups and strong tradition of political activism, these women exerted tangible pressure on Philadelphia’s political leaders to reshape the reform agenda. When success was not forthcoming through traditional political means, African American women developed alternate strategies to secure their political agenda. While this dissertation is a traditional social and political history, it will also combine elements of biography in order to reconstruct the lives of Philadelphia’s African American political women. This work does not describe a united sisterhood among women or portray this period as one of unparalleled success. Rather, this dissertation will bring a new balance to political history that highlights the importance of local political activism and is at the same time sensitive to issues of race, gender, and class. -

Women--Their Social and Economic Status. Selected References. INSTITUTIJN Department of Labor, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 049 371 VT 012 825 AUTHOR Dupont, Julie A. TITLE Women--Their Social and Economic Status. Selected References. INSTITUTIJN Department of Labor, Washington, D.C. Library. PUB DATE Dec 70 NOTE 46p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Bibliographies, *Economic Status, Federal Legislation, *Females, *Social Status, Working Women ABSTRACT The 396 publications that treat various aspects ot the social and economic status ot women are organized alphabetically by author under these categories: (1) General, (2) Historical, and (3) 19th and 20th Centuries. Each entry includes the author, title, publication information, pagination, an occasional description of the contents, Library of Congress call number, and symbols representing the library holding the document. In addition to the bibliography, a orief description of the Women's Bureau and legislation relating to its founding, and an annotated listing of 23 collections of materials relating to women are provided. (SB) r-iti reN as -4- WOMEN THEIR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STATUS C) L.LJ SELECTED REFERENCES DECEMBER, 1970 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR I WOMEN THEIR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STATUS SELECTED REFERENCES DECEMBER, 1910 Prepared By Julie A. Dupont Bibliographer U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THEPERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POINTSOF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DONOT NECES SARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEOF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR J. D. Hodgson, -

Making Her Mark: Philadelphia Women Fight for the Vote

Making Her Mark: Philadelphia Women Fight for the Vote Philadelphia women have long led the charge to expand voting rights. After decades of activism, women won the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment in August 1920. But many women were excluded. The fight continues. “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.” —Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, 1866 Black and white print portrait of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Making Her Mark is a production of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Parkway Central Library, November 2020–October 2021 Curated by Jennifer Zarro, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Instruction, Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University, with Suzanna Urminska. Exhibition design by Nathanael Roesch, Ph.D., Josey Driscoll, and Jonai Gibson-Selix. Special thanks to Alix Gerz, Christine Miller, Andrew Nurkin, and Kalela Williams. Drawn from the collections of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection and Special Collections Research Center at Temple University Libraries, Cumberland County Historical Society, Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, The Library Company of Philadelphia, Library of Congress, Massachusetts Historical Society, National Gallery of Art, National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, The New York Public Library, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, U.S. House of Representatives, University of Delaware Library, University of Pennsylvania Archives, Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. The Free Library acknowledges that the land on which the library stands is called Lenapehoking, the traditional territory of the Lenni-Lenape peoples. -

The Project Gutenberg Etext of Jailed for Freedom, by Doris Stevens

The Project Gutenberg Etext of Jailed for Freedom, by Doris Stevens Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the laws for your country before redistributing these files!!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Please do not remove this. This should be the first thing seen when anyone opens the book. Do not change or edit it without written permission. The words are carefully chosen to provide users with the information they need about what they can legally do with the texts. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below, including for donations. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a 501(c)(3) organization with EIN [Employee Identification Number] 64-6221541 Title: Jailed for Freedom Author: Doris Stevens Release Date: January, 2003 [Etext #3604] [Yes, we are about one year ahead of schedule] [The actual date this file first posted = 06/12/01] Edition: 10 Language: English The Project Gutenberg Etext of Jailed for Freedom, by Doris Stevens *******This file should be named j4fre10.txt or j4fre10.zip******* Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, j4fre11.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, j4fre10a.txt Prepared by: Samuel R. Brown [email protected] Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. -

Works Cited Primary Sources Periodicals "Alice Paul to Fight On: Will Demand That She Be Treated As a 'Political Prison

Works Cited Primary Sources Periodicals "Alice Paul to Fight On: Will Demand That She Be Treated as a 'Political Prisoner.'" The New York Times, 25 Oct. 1917. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times, search.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/99871732/63B26C8E707A49A5PQ/18? accountid=35196. Accessed 16 Jan. 2017. This is a short article published on Alice Paul's arrest, and it talks about how she wanted to be treated like a political prisoner while in jail, instead of just an ordinary criminal. This wish shows that Paul and other suffragists did not believe that fighting for women's suffrage was a crime, while government officials did. Also, the fact that this article was published, even though it is relatively short, shows that the nation was kept up-to-date on the suffrage movement, and people did want to hear about the happenings of this movement. "Arrest Four More Pickets: Miss Alice Paul among the Quartet in White House Demonstration." The New York Times, 20 Oct. 1917. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times, search.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/99842295/63B26C8E707A49A5PQ/19? accountid=35196. Accessed 16 Jan. 2017. This is a short article published in the NY Times, which states that Alice Paul was one of the four picketers arrested while picketing the White House. This article is just one of many published with very similar contents: briefly reporting that women had been arrested for picketing. However, this series of articles together shows that women refused to stop picketing, even though many of them were arrested. Also, the arrests were in some ways good for the movement because they gained publicity and allowed for women to continue peacefully resisting in jail through hunger strikes. -

The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

THE WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Volume 54 July 1971 Number 3 SPEAKERS FOR WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN PENNSYLVANIA L. E. Preston I.Quakers Make the Opening Remarks !folks talk about—women's preaching as tho* it was next to Whyhighway robbery eyes astare and mouth agape," wrote Theodore Weld, a staunch abolitionist, to the famous Grimke sisters on July 22, 1837. "Pity women were not born with a split stick on their tongues !Ghostly dictums have fairly beaten it into heads of the whole world save a fraction, that mind is sexed, and Human rights are sex'd, moral obligation sex'd; and to carry out the farce they'll ... all turn in to pairing off in couples matrimonial, consciences, accounta- bilities, arguments, duties, philosophy, facts, and theories in the abstract." l Angelina Grimke agreed, "My"auditors literally sit sometimes with 'mouths agape and eyes astare/ she wrote inreply to Theodore Weld on August 12, 1837, "so that Icannot help smiling in the midst of 'rhetorical flourishes' to witness their perfect amazement at hearing a woman speak inthe churches." 2 The sisters, Sarah and Angelina Grimke, were pioneers in open- ing the way for public speaking to women. There were many "mouths Dr. Preston, associate professor in the Speech Department at the Pennsyl- vania State University, is also a playwright with eleven published plays. His special interests in teaching are radio and television production. —Editor 1 The Letters of Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimke Weld and Sarah Grimke, 1822-1844 (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1934), 412. 2 Ibid., 414. 246 L. -

National American Woman Suffrage Association 505 Fifth Avenue New York City Prznrd by N

THE HAND BOOK OF THE NATIONAL AMERICAN WOMAN ...b. SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTY- SIXTH ANNUAL CONVENTION HELD AT NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE NOVEMBER 12-1 7 (INCLUSIVE) , 1914 NATIONAL AMERICAN WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION 505 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK CITY PRZNRD BY N. W. 1. PUOLIBBINC8 00.9 INC. ..- , CONTENTS PAGE Affiliated Members. List of .................................... 200 Affiliated Members. Report of................................. 132 Associate Members. List of.................................... 211 Auditors.Report of............................................ 48 Call ........................................................... 9 CampaignCommittee. Report of Special .......................117 Campaign States.List of ....................................... 13 Campaign States. Report of .................................... 144 Church Work Committee. Report of........................... 127 Congressional Committee. FinancialStatement .................. 53 Congressional Committee. Report of ............................ 76 Constitution and By-Laws ...................................... 191 Constitution Requirements ..................................... II ConventionPolicies and General Platform ...................... II Co-operating Members .......................................... 211 CredentialsCommittee. Report of ............................... 55 Data Department, Report of .................................... 64 Delegates Present at Convention ................................ 183 Elections Committee. Report of